|

|

|

|

|

RODENTS: Woodchuck |

|

|

Identification

The woodchuck (Marmota

monax, Fig. 1), a member of the squirrel family, is

also known as the “ground hog” or “whistle pig.” It is

closely related to other species of North American

marmots. It is usually grizzled brownish gray, but white

(albino) and black (melanistic) individuals can

occasionally be found. The woodchuck’s compact, chunky

body is supported by short strong legs. Its forefeet

have long, curved claws that are well adapted for

digging burrows. Its tail is short, well furred, and

dark brown.

Both sexes are similar in

appearance, but the male is slightly larger, weighing an

average of 5 to 10 pounds (2.2 to 4.5 kg). The total

length of the head and body averages 16 to 20 inches (40

to 51 cm). The tail is usually 4 to 7 inches (10 to 18

cm) long. Like other rodents, woodchucks have white or

yellowish-white, chisel-like incisor teeth. Their eyes,

ears, and nose are located toward the top of the head,

which allows them to remain concealed in their burrows

while they check for danger over the rim or edge.

Although they are slow runners, woodchucks are alert and

scurry quickly to their dens when they sense danger.

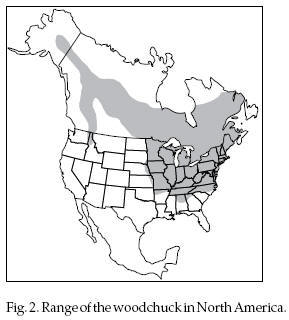

Range Range

Woodchucks occur

throughout eastern and central Alaska, British Columbia,

and most of southern Canada. Their range in the United

States extends throughout the East, northern Idaho,

northeastern North Dakota, southeastern Nebraska,

eastern Kansas, and northeastern Oklahoma, as well as

south to Virginia and northern Alabama (Fig. 2).

Habitat

In general, woodchucks

prefer open farmland and the surrounding wooded or

brushy areas adjacent to open land. Burrows commonly are

located in fields and pastures, along fence rows, stone

walls, roadsides, and near building foundations or the

bases of trees. Burrows are almost always found in or

near open, grassy meadows or fields. Woodchuck burrows

are distinguished by a large mound of excavated earth at

the main entrance. The main opening is approximately 10

to 12 inches (25 to 30 cm) in diameter. There are two or

more entrances to each burrow system. Some secondary

entrances are dug from below the ground and do not have

mounds of earth beside them. They are usually well

hidden and sometimes difficult to locate (Fig. 3).

During spring, active burrows can be located by the

freshly excavated earth at the main entrance. The burrow

system serves as home to the woodchuck for mating,

weaning young, hibernating in winter, and protection

when threatened.

Food Habits

Woodchucks prefer to feed

in the early morning and evening hours. They are strict

herbivores and feed on a variety of vegetables, grasses,

and legumes. Preferred foods include soybeans, beans,

peas, carrot tops, alfalfa, clover, and grasses.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Woodchucks are primarily

active during daylight hours. When not feeding, they

sometimes bask in the sun during the warmest periods of

the day. They have been observed dozing on fence posts,

stone walls, large rocks, and fallen logs close to the

burrow entrance. Woodchucks are good climbers and

sometimes are seen in lower tree branches. Woodchucks

are among the few mammals that enter into true

hibernation. Hibernation generally starts in late fall,

near the end of October or early November, but varies

with latitude. It continues until late February and

March. In northern latitudes, torpor can start earlier

and end later. Males usually come out of hibernation

before females and subadults. Males may travel long

distances, and occasionally at night, in search of a

mate. Woodchucks breed in March and April. A single

litter of 2 to 6 (usually 4) young is produced each

season after a gestation period of about 32 days. The

young are born blind and hairless. They are weaned by

late June or early July, and soon after strike out on

their own. They frequently occupy abandoned dens or

burrows. The numerous new burrows that appear during

late summer are generally dug Fig. 3. Burrow system of

the woodchuck. Side entrance Nest chamber Main entrance

Fig. 2. Range of the woodchuck in North America. B-185

by older woodchucks. The life span of a woodchuck is

about 3 to 6 years. Woodchucks usually range only 50 to

150 feet (15 to 30 m) from their den during the daytime.

This distance may vary, however, during the mating

season or based on the availability of food. Woodchucks

maintain sanitary den sites and burrow systems,

replacing nest materials frequently. A burrow and den

system is often used for several seasons. The tunnel

system is irregular and may be extensive in size.

Burrows may be as deep as 5 feet (1.5 m) and range from

8 to 66 feet (2.4 to 19.8 m) in total length (Fig. 3).

Old burrows not in use by woodchucks provide cover for

rabbits, weasels, and other wildlife. When startled, a

woodchuck may emit a shrill whistle or alarm, preceded

by a low, abrupt “phew.” This is followed by a low,

rapid warble that sounds like “tchuck, tchuck.” The call

is usually made when the animal is startled at the

entrance of the burrow. The primary predators of

woodchucks include hawks, owls, foxes, coyotes, bobcats,

weasels, dogs, and humans. Many woodchucks are killed on

roads by automobiles.

Damage

On occasion, the

woodchuck’s feeding and burrowing habits conflict with

human interests. Damage often occurs on farms, in home

gardens, orchards, nurseries, around buildings, and

sometimes around dikes. Damage to crops such as alfalfa,

soybeans, beans, squash, and peas can be costly and

extensive. Fruit trees and ornamental shrubs are damaged

by woodchucks as they gnaw or claw woody vegetation.

Gnawing on underground power cables has caused

electrical outages. Damage to rubber hoses in vehicles,

such as those used for vacuum and fuel lines, has also

been documented. Mounds of earth from the excavated

burrow systems and holes formed at burrow entrances

present a hazard to farm equipment, horses, and riders.

On occasion, burrowing can weaken dikes and foundations.

Legal Status In most states, woodchucks are considered

game animals. There is usually no bag limit or closed

season. In damage situations, woodchucks are usually not

protected. The status may vary from state to state,

depending on the control technique to be employed.

Consult with your state wildlife department,

USDA-APHIS-Animal Damage Control representative, or

extension agent before shooting and/or trapping problem

individuals.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Fencing can help reduce

woodchuck damage. Woodchucks, however, are good climbers

and can easily scale wire fences if precautions are not

taken. Fences should be at least 3 feet (1 m) high and

made of heavy poultry wire or 2-inch (5-cm) mesh woven

wire. To prevent burrowing under the fence, bury the

lower edge 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 cm) in the ground

or bend the lower edge at an L-shaped angle leading

outward and bury it in the ground 1 to 2 inches (2.5 to

5 cm). Fences should extend 3 to 4 feet (0.9 to 1.2 m)

above the ground. Place an electric wire 4 to 5 inches

(10 to 13 cm) off the ground and the same distance

outside the fence. When connected to a UL-approved fence

charger, the electric wire will prevent climbing and

burrowing. Bending the top 15 inches (38 cm) of wire

fence outward at a 45o angle will also prevent climbing

over the fence. Fencing is most useful in protecting

home gardens and has the added advantage of keeping

rabbits, dogs, cats, and other animals out of the garden

area. In some instances, an electric wire alone, placed

4 to 5 inches (10 to 13 cm) above the ground, has

deterred woodchucks from entering gardens. Vegetation in

the vicinity of any electric fence should be removed

regularly to prevent the system from shorting out.

Frightening

Devices Scarecrows and

other effigies can provide temporary relief from

woodchuck damage. Move them regularly and incorporate a

high level of human activity in the susceptible area.

Repellents None are

registered.

Toxicants None are

registered for woodchuck control.

Fumigants

Gas cartridge (carbon monoxide). The most common

means of woodchuck control is the use of commercial gas

cartridges. They are specially designed cardboard

cylinders filled with slow-burning chemicals. They are

ignited and placed in burrow systems, and all entrances

are sealed. As the gas cartridges burn, they produce

carbon monoxide and other gases that are lethal to

woodchucks. Gas cartridges are a General Use Pesticide

and are available from local farm supply stores, certain

USDA-APHIS-ADC state and district offices, and the

USDA-APHIS-ADC Pocatello Supply Depot. Directions for

their use are on the label and should be carefully read

and closely followed (see information on gas cartridges

in the Pesticides and Supplies and Materials sections).

Be careful when using gas cartridges. Do not use them in

burrows located under wooden sheds, buildings, or near

other combustible materials because of the potential

fire hazard. Gas cartridges are ignited by lighting a

fuse. They will not explode if properly prepared and

used. Caution should be taken to avoid prolonged

breathing of fumes.

Each burrow system should

be treated in the following manner:

1. Locate the main burrow

opening (identified by a mound of excavated soil) and

all other secondary entrances associated with that

burrow system. B-186

2. With a spade, cut a

clump of sod slightly larger than each opening. Place a

piece of sod over each entrance except the main

entrance. Leave a precut sod clump next to the main

entrance for later use. 3. Prepare the gas cartridge for

ignition and placement following the written

instructions on the label. 4. Kneel at the main burrow

opening, light the fuse, and immediately place (do not

throw) the cartridge as far down the hole as possible.

5. Immediately after

positioning the ignited cartridge in the burrow, close

the main opening or all openings, if necessary, by

placing the pieces of precut sod, grass side down, over

the opening. Placing the sod with the grass side down

prevents smothering the lit cartridge. Make a tight seal

by packing loose soil over the piece of sod. Look

carefully for smoke leaking from the burrow system and

cover or reseal any openings that leak.

6. Continue to observe the

site for 4 to 5 minutes and watch nearby holes. Continue

to reseal those from which smoke is escaping.

7. Repeat these steps

until all burrow systems have been treated in problem

areas. Burrows can be treated with gas cartridges at any

time. This method is most effective in the spring before

the young emerge. On occasion, treated burrows will be

reopened by another animal reoccupying the burrow

system. If this occurs, retreatment may be necessary.

Aluminum Phosphide.

Aluminum phosphide is a Restricted Use Pesticide and can

be applied only by a certified pesticide applicator.

Treatment of burrow systems is relatively easy. Place

two to four tablets deep into the main burrow. Plug the

burrow openings with crumpled newspapers and then pack

the openings with loose soil. All burrows must be sealed

tightly but avoid covering the tablets with soil. The

treatment site should be inspected 24 to 48 hours later

and opened burrows should be retreated.

Aluminum phosphide in the

presence of moisture in the burrow produces hydrogen

phosphide (phosphine) gas. Therefore, soil moisture and

a tightly sealed burrow system are important. The

tablets are presently approved for outdoor use on

noncropland and orchards for burrowing rodents. Tablets

should not be used within 15 feet (5 m) of any occupied

building or structure or where gases could escape into

areas occupied by other animals or humans. Storage of

unused tablets is critical — they must be kept in their

original container, in a cool, dry, locked, and

ventilated room. They must be protected from moisture,

open flames, and heat.

The legal application and

use of aluminum phosphide for woodchuck control may vary

from state to state. Check with your state pesticide

registration board, USDA-APHIS-ADC representative, or

extension agent when considering use of this material.

Aluminum phosphide should always be applied as directed

on the label.

Trapping

Steel leghold and live traps. Traps may also be used

to reduce woodchuck damage, especially in or near

buildings. Both steel leghold and live traps are

effective. Trapping should be used in areas where gas

cartridges or aluminum phosphide may create a fire

hazard or where fumes may enter areas to be protected.

Woodchucks are strong animals and a No. 2 steel trap is

needed to hold them. Before using steel traps, consult

your state wildlife department or USDA-APHIS-ADC

representative for trapping regulations. Steel traps

should not be employed in areas where there is a

possibility of capturing pets or livestock. Live

trapping can sometimes be difficult, but is effective.

Live traps can be built at

home, purchased from commercial sources (see Supplies

and Materials), or borrowed. Bait traps with apple

slices or vegetables such as carrots and lettuce, and

change baits daily. Locate traps at main entrances or

major travel lanes. Place guide logs on either side of

the path between the burrow opening and the trap to help

funnel the animal into the trap. Check all traps twice

daily, morning and evening, so that captured animals may

be quickly removed. A captured animal can be relocated

to an area with suitable habitat where no additional

damage can be caused. The animal can also be euthanized

by lethal injection (by a veterinarian or under

veterinarian supervision), by shooting, or by carbon

dioxide gas.

Conibear® traps.

Conibear® traps are effective in some situations. A set

in a travelway, such as between a wood pile and barn,

can be very effective. Sets can also be made at the main

entrance of the burrow system. Logs, sticks, stones, and

boards should be used to block travelways around the set

and/or to lead the animal into the set. No bait is

necessary for Conibear® sets. Conibear® 110s, 160s, and

220s are best suited for woodchuck control. Conibears®

are well suited for use near or under structures in

which fumigants and shooting present a hazard. Conibear®

110s will handle young, small animals, while 160s and

220s will also handle larger adults. Conibear® traps

kill the animal quickly and care should be taken to

avoid trapping domestic animals such as cats and dogs.

Some state or local laws prohibit the use of Conibear®

traps except in water. Consult your state wildlife

department or USDA-APHIS-ADC office for regulations.

Shooting

In many states, woodchucks are considered game

animals. Therefore, if shooting is permitted, a valid

state hunting license may be required. In some states

there is no closed season, nor is there usually any

limit on the number of woodchucks that can be taken by

hunters. If shooting can be accomplished safely,

landowners and/or hunters can reduce or maintain a low

population of woodchucks where necessary. Landowners and

hunters should agree on hunting arrangements prior to

initiating any shooting activities. Another alternative

would be to have a professional USDA-APHIS-ADC

representative do the job. He or she will be familiar

with legalities and techniques. Contracting with a

Animal Damage Control professional would be especially

valuable when and where large numbers of woodchucks are

causing serious economic losses. Shooting can be used as

a follow-up to other, more substantial control

activities.

Rifles with telescopic

sights are commonly used in the sport shooting of

woodchucks. A variety of calibers can be used, but

.22-caliber centerfire rifles are most popular.

Occasionally, shotguns are used to eliminate woodchucks

that are causing damage. The objective is to remove the

animal as humanely as possible without wounding it.

Shotgun gauge, range, and shot size should be considered

when using this method. Use a 12-gauge with No. 4 to No.

6 shot. The range should be within 25 yards (23 m).

Carefully assess the area behind and around the target

for safety. Pellets can ricochet, causing injury or

serious damage in background areas. Use of a rifle or

shotgun should be conducted only if good shooting

conditions exist.

Acknowledgments

I thank the state

directors of USDA-APHISADC, whose comments and editing

improved this publication. Figures 1 through 3 from

Schwartz and Schwartz (1981), adapted by Jill Sack

Johnson.

For

Additional Information

Burt, W. H., and R. P.

Grossenheider. 1976. A field guide to the mammals. 3d

ed. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. 289 pp.

Lee, D. S., and J. B.

Funderburg. 1982. Marmots. Pages 176-191 in J. A.

Chapman and G. A. Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North

America: biology, management, and economics. The Johns

Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Marsh, R. E., and W. E.

Howard. 1990. Vertebrate pests. Pages 791-861 in A.

Mallis, ed. Handbook of pest control, 7th ed. Franzak

and Foster Co., Cleveland, Ohio.

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri. Rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp.

Whitaker, J. O. Jr. 1980.

Audubon Society field guide to North American mammals.

6th ed. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. New York.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska - Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

03/12/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|