|

|

|

|

|

RODENTS: Nutria |

|

|

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods Exclusion

- Exclusion

Protect small areas with partially buried fences.

Wire tubes can be used to protect baldcypress or

other seedlings but are expensive and difficult to

use.

Use sheet metal shields to prevent gnawing on wooden

and styrofoam structures and trees near aquatic

habitat.

Install bulkheads to deter burrowing into banks.

- Cultural Methods

and Habitat Modification

Improve drainage to destroy travel lanes.

Manage vegetation to eliminate food and cover.

Contour stream banks to control burrowing.

Plant baldcypress seedlings in the fall to minimize

losses.

Restrict farming, building construction, and other

“high risk” activities to upland sites away from

water to prevent damage.

Manipulate water levels to stress nutria

populations.

- Frightening

Ineffective.

- Repellents

None are registered. None are effective.

- Toxicants

Zinc phosphide on carrot or sweet potato baits.

- Fumigants

None are registered. None are effective.

- Trapping

Commercial harvest by trappers.

Double longspring traps, Nos. 11 and 2, as preferred

by trappers and wildlife damage control specialists.

Body-gripping traps, for example, Conibear® Nos.

160-2 and 220-2, and locking snares are most

effective when set in trails, den entrances, or

culverts.

Live traps should be used when leghold and

body-gripping traps cannot be set.

Long-handled dip nets can be used to catch unwary

nutria.

- Shooting

Effective when environmental conditions force nutria

into the open. Night hunting is illegal in many

states.

- Other Methods

Available control techniques may not be applicable

to all damage situations. In these cases, safe and

effective methods must be tailored to specific

problems.

Identification

The nutria (Myocastor

coypus, Fig. 1) is a large, dark-colored,

semiaquatic rodent that is native to southern South

America. At first glance, a casual observer may

misidentify a nutria as either a beaver (Castor

canadensis) or a muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus),

especially when it is swimming. This superficial

resemblance ends when a more detailed study of the

animal is made. Other names used for the nutria include

coypu, nutria-rat, South American beaver, Argentine

beaver, and swamp beaver.

Nutria are members of the

family Myocastoridae. They have short legs and a robust,

highly arched body that is approximately 24 inches (61

cm) long. Their round tail is from 13 to 16 inches (33

to 41 cm) long and scantily haired. Males are slightly

larger than females;the average weight for each is about

12 pounds

(5.4 kg). Males and

females may grow to 20 pounds (9.1 kg) and 18 pounds

(8.2 kg), respectively.

The dense grayish underfur

is overlaid by long, glossy guard hairs that vary in

color from dark brown to yellowish brown. The forepaws

have four well-developed and clawed toes and one

vestigial toe. Four of the five clawed toes on the hind

foot are interconnected by webbing; the fifth outer toe

is free. The hind legs are much larger than the

forelegs. When moving on land, a nutria may drag its

chest and appear to hunch its back. Like beavers, nutria

have large incisors that are yel-low-orange to

orange-red on their outer surfaces.

In addition to having

webbed hind feet, nutria have several other adaptations

to a semiaquatic life. The eyes, ears, and nostrils of

nutria are set high on their heads. Additionally, the

nostrils and mouth have valves that seal out water while

swimming, diving, or feeding underwater. The mammae or

teats of the female are located high on the sides, which

allows the young to suckle while in the water. When

pursued, nutria can swim long distances under water and

see well enough to evade capture.

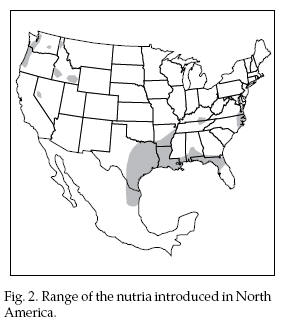

Range Range

The original range of

nutria was south of the equator in temperate South

America. This species has been introduced into other

areas, primarily for fur farming, and feral populations

can now be found in North America, Europe, the Soviet

Union, the Middle East, Africa, and Japan. M. c.

bonariensis was the primary subspecies of nutria

introduced into the United States.

Fur ranchers, hoping to

exploit new markets, imported nutria into California,

Washington, Oregon, Michigan, New Mexico, Louisiana,

Ohio, and Utah between 1899 and 1940. Many of the nutria

from these ranches were freed into the wild when the

businesses failed in the late 1940s. State and federal

agencies and individuals translocated nutria into

Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland,

Mississippi, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Texas, with the

intent that nutria would control undesirable vegetation

and enhance trapping opportunities. Nutria were also

sold as “weed cutters” to an ignorant public throughout

the Southeast. A hurricane in the late 1940s aided

dispersal by scattering nutria over wide areas of

coastal southwest Louisiana and southeast Texas.

Accidental and intentional

releases have led to the establishment of widespread and

localized populations of nutria in various wetlands

throughout the United States. Feral animals have been

reported in at least 40 states and three Canadian

provinces in North America since their introduction.

About one-third of these states still have viable

populations that are stable or increasing in number.

Some of the populations are economically important to

the fur industry. Adverse climatic conditions,

particularly extreme cold, are probably the main factors

limiting range expansion of nutria in North America.

Nutria populations in the United States are most dense

along the Gulf Coast of Louisiana and Texas (Fig. 2)

Habitat

Nutria adapt to a wide variety of

environmental conditions and persist in areas previously

claimed to be unsuitable. In the United States, farm

ponds and other freshwater impoundments, drainage canals

with spoil banks, rivers and bayous, freshwater and

brackish marshes, swamps, and combinations of various

wetland types can provide a home to nutria. Nutria

habitat, in general, is the semiaquatic environment that

occurs at the boundary between land and permanent water.

This zone usually has an abundance of emergent aquatic

vegetation, small trees, and/or shrubs and may be

interspersed with small clumps and hillocks of high

ground. In the United States, all significant nutria

populations are in coastal areas, and freshwater marshes

are the preferred habitat.

Food

Habits

Nutria are

almost entirely herbivorous and eat animal material

(mostly insects) incidentally, when they feed on plants.

Freshwater mussels and crustaceans are occasionally

eaten in some parts of their range. Nutria are

opportunistic feeders and eat approximately 25% of their

body weight daily. They prefer several small meals to

one large meal.

The succulent, basal

portions of plants are preferred as food, but nutria

also eat entire plants or several different parts of a

plant. Roots, rhizomes, and tubers are especially

important during winter. Important food plants in the

United States include cordgrasses (Spartina spp.),

bulrushes (Scirpus spp.), spikerushes (Eleocharis spp.),

chafflower (Alternanthera spp.), pickerelweeds (Pontederia

spp.), cattails (Typha spp.), arrowheads (Sagittaria spp.),

and flatsedges (Cyperus spp.). During winter, the bark

of trees such as black willow (Salix nigra) and

bald-cypress (Taxodium distichum) may be eaten. Nutria

also eat crops and lawn grasses found adjacent to

aquatic habitat.

Because of their dexterous

forepaws, nutria can excavate soil and handle very small

food items. Food is eaten in the water; on feeding

platforms constructed from cut vegetation; at floating

stations supported by logs, decaying mats of vegetation,

or other debris; in shallow water; or on land. In some

areas, the tops of muskrat houses and beaver lodges may

also be used as feeding platforms.

General

Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

General Biology

In the wild,

most nutria probably live less than 3 years; captive

animals, however, may live 15 to 20 years. Predation,

disease and parasitism, water level fluctuations,

habitat quality, highway traffic, and weather extremes

affect mortality. Annual mortality of nutria is between

60% and 80%.

Predators of nutria

include humans (through regulated harvest), alligators

(Alligator mississippiensis), garfish (Lepisosteus spp.),

bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), and other birds

of prey, turtles, snakes such as the cottonmouth (Agkistrodon

piscivorus), and several carnivorous mammals.

Nutria densities vary

greatly. In Louisiana, autumn densities of about 18

animals per acre (44/ha) have been found in floating

freshwater marshes. In Oregon, summer densities in

freshwater marshes may be 56 animals per acre (138/ha).

Sex ratios range from 0.6 to 1.6 males per female.

In summer, nutria live on

the ground in dense vegetation, but at other times of

the year they use burrows. Burrows may be those

abandoned by other animals such as armadillos (Dasypus

novemcinctus), beavers, and muskrats, or they may be dug

by nutria. Underground burrows are used by individuals

or multigenerational family groups.

Burrow entrances are

usually located in the vegetated banks of natural and

human-made waterways, especially those having a slope

greater than 45o. Burrows range from a simple, short

tunnel with one entrance to complex systems with several

tunnels and entrances at different levels. Tunnels are

usually 4 to 6 feet (1.2 to 1.8 m) long; however,

lengths of up to 150 feet (46 m) have been recorded.

Compartments within the tunnel system are used for

resting, feeding, escape from predators and the weather,

and other activities. These vary in size, from small

ledges that are only 1 foot (0.3 m) across to large

family chambers that measure 3 feet (0.9 m) across. The

floors of these chambers are above the water line and

may be covered with plant debris discarded during

feeding and shaped into crude nests.

In addition to using land

nests and burrows, nutria often build flattened circular

platforms of vegetation in shallow water. Constructed of

coarse emergent vegetation, these platforms are used for

feeding, loafing, grooming, birthing, and escape, and

are often misidentified as muskrat houses. Initially,

platforms may be relatively low and inconspicuous;

however, as vegetation accumulates, some may attain a

height of 3 feet (0.9 m).

Reproduction

Nutria breed in

all seasons throughout most of their range, and sexually

active individuals are present every month of the year.

Reproductive peaks occur in late winter, early summer,

and mid-autumn, and may be regulated by prevailing

weather conditions.

Under optimal conditions,

nutria reach sexual maturity at 4 months of age. Female

nutria are polyestrous, and nonpregnant females cycle

into estrus (“heat”) every 2 to 4 weeks. Estrous is

maintained for 1 to 4 days in most females. Sexually

mature males can breed at any time because sperm is

produced throughout the year.

The gestation period for

nutria ranges from 130 to 132 days. A postpartum estrus

occurs within 48 hours after birth and most females

probably breed again during that time.

Litters average 4 to 5

young, with a range of 1 to 13. Litter sizes are

generally smaller during winter, in suboptimal habitats,

and for young females. Females often abort or assimilate

embryos in response to adverse environmental conditions.

Young are precocial and

are born fully furred and active. They weigh

approximately 8 ounces (227 g) at birth and can swim and

eat vegetation shortly thereafter. Young normally suckle

for 7 to 8 weeks until they are weaned.

Behavior

Nutria tend to

be crepuscular and nocturnal, with the start and end of

activity periods coinciding with sunset and sunrise,

respectively. Peak activity occurs near midnight. When

food is abundant, nutria rest and groom during the day

and feed at night. When food is limited, daytime feeding

increases, especially in wetlands free from frequent

disturbance.

Nutria generally occupy a

small area throughout their lives. In Louisiana, the

home range of nutria is about 32 acres (13 ha). Daily

cruising distances for most nutria are less than 600

feet (183 m), although some individuals may travel much

farther. Nutria move most in winter, due to an increased

demand for food. Adults usually move farther than young.

Seasonal migrations of nutria may also occur. Nutria

living in some agricultural areas move in from marshes

and swamps when crops are planted and leave after the

crops are harvested.

Nutria have relatively

poor eyesight and sense danger primarily by hearing.

They occasionally test the air for scent. Although they

appear to be clumsy on land, they can move with

surprising speed when disturbed. When frightened, nutria

head for the nearest water, dive in with a splash, and

either swim underwater to protective cover or stay

submerged near the bottom for several minutes. When

cornered or captured, nutria are aggressive and can

inflict serious injury to pets and humans by biting and

scratching.

Damage and

Damage Identification

Kinds of Damage

Nutria damage

has been observed throughout their range. Most damage is

from feeding or burrowing. In the United States, most

damage occurs along the Gulf Coast of Louisiana and

Texas. The numerous natural and human-made waterways

that traverse this area are used extensively for travel

by nutria.

Burrowing is the most

commonly reported damage caused by nutria. Nutria are

notorious in Louisiana and Texas for undermining and

breaking through water-retaining levees in flooded

fields used to produce rice and crawfish. Additionally,

nutria burrows sometimes weaken flood control levees

that protect low-lying areas. In some cases, tunneling

in these levees is so extensive that water will flow

unobstructed from one side to the other, necessitating

their complete reconstruction.

Nutria sometimes burrow

into the Styrofoam flotation under boat docks and

wharves, causing these structures to lean and sink. They

may burrow under buildings, which may lead to uneven

settling or failure of the foundations. Burrows can

weaken roadbeds, stream banks, dams, and dikes, which

may collapse when the soil is saturated by rain or high

water or when subjected to the weight of heavy objects

on the surface (such as vehicles, farm machinery, or

grazing livestock). Rain and wave action can wash out

and enlarge collapsed burrows and compound the damage.

Nutria depredation on

crops is well documented. In the United States,

sugarcane and rice are the primary crops damaged by

nutria. Grazing on rice plants can significantly reduce

yields, and damage can be locally severe. Sugarcane

stalks are often gnawed or cut during the growing

season. Often only the basal internodes of cut plants

are eaten. Other crops that have been damaged include

corn, milo (grain sorghum), sugar and table beets,

alfalfa, wheat, barley, oats, peanuts, various melons,

and a variety of vegetables from home gardens and truck

farms.

Nutria girdle fruit, nut,

and shade trees and ornamental shrubs. They also dig up

lawns and golf courses when feeding on the tender roots

and shoots of sod grasses. Gnawing damage to wooden

structures is common. Nutria also gnaw on styrofoam

floats used to mark the location of traps in commercial

crawfish ponds.

At high densities and

under certain adverse environmental conditions, foraging

nutria can significantly impact natural plant

communities. In Louisiana, nutria often feed on seedling

baldcypress and can cause the complete failure of

planted or naturally-regenerated stands. Overutilization

of emergent marsh plants can damage stands of desirable

vegetation used by other wildlife species and aggravate

coastal erosion problems by destroying vegetation that

holds marsh soils together. Nutria are fond of grassy

arrowhead (Sagittaria platyphylla) tubers and may

destroy stands propagated as food for waterfowl in

artificial impoundments.

Nutria can be infected

with several pathogens and parasites that can be

transmitted to humans, livestock, and pets. The role of

nutria, however, in the spread of diseases such as

equine encephalomyelitis, leptospirosis, hemorrhagic

septicemia (Pasteurellosis), paratyphoid, and

salmonellosis is not well documented. They may also host

a number of parasites, including the nematodes and blood

flukes that cause “swimmer’s-itch” or “nutria-itch” (Strongyloides

myopotami and Schistosoma mansoni), the protozoan

responsible for giardiasis (Giardia lamblia), tapeworms

(Taenia spp.), and common liver flukes (Fasciola

hepatica). The threat of disease may be an important

consideration in some situations, such as when livestock

drink from water contaminated by nutria feces and urine.

Damage Identification

The ranges of

nutria, beavers, and muskrats overlap in many areas and

damage caused by each may be similar in appearance.

Therefore, careful examination of sign left at the

damage site is necessary to identify the responsible

species.

On-site observations of

animals and their burrows are the best indicators of the

presence of nutria. Crawl outs, slides, trails, and the

exposed entrances to burrows often have tracks that can

be used to identify the species. The hind foot, which is

about 5 inches (13 cm) long, has four webbed toes and a

free outer toe. A drag mark left by the tail may be

evident between the footprints (Fig. 3).

Droppings may be found

floating in the water, along trails, or at feeding

sites. These are dark green to almost black in color,

cylindrical, and approximately 2 inches (5 cm) long and

1/2 inch (1.3 cm) in diameter. Additionally, each

dropping usually has deep, parallel grooves along its

entire length (Fig. 4).

Trees girdled by nutria

often have no tooth marks, and bark may be peeled from

the trunk. The crowns of seedling trees are usually

clipped (similar to rabbit [Sylvilagus spp.] damage) and

discarded along with other woody portions of the plant.

In rice fields, damage

caused by nutria, muskrats, and Norway rats (Rattus

norvegicus) can be confused. Nutria and muskrats damage

rice plants by clipping stems at the water line in

flooded fields; Norway rats reportedly clip stems above

the surface of the water (E. A. Wilson, personal

communication).

Legal

Status

Nutria are protected as

furbearers in some states or localities because they are

economically important. Permits may be necessary to

control animals that are damaging property. In other

areas, nutria have no legal protection and can be taken

at any time by any legal means. Consequently, citizens

experiencing problems with nutria should be familiar

with local wildlife laws and regulations. Complex

problems should be handled by professional wildlife

damage control specialists who have the necessary

permits and expertise to do the job correctly. Your

state wildlife agency can provide the names of qualified

wildlife damage control specialists and information on

pertinent laws and regulations.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Preventive measures should

be used whenever possible, especially in areas where

damage is prevalent. When control is warranted, all

available techniques should be considered before a

control plan is implemented. The objective of control is

to use only those techniques that will stop or alleviate

anticipated or ongoing damage or reduce it to tolerable

levels. In most cases, successful control will depend on

integrating a number of different techniques and

methods.

Timing and location of

control activities are important factors governing the

success or failure of any control project. Control in

sugarcane, for example, is best applied during the

growing season, after damage has started. At this time,

nutria in affected areas are relatively stationary and

concentrated in drainages adjacent to fields.

Conversely, efforts to protect rice field levees or the

shorelines of southern lakes and ponds should be

initiated during the winter when animals are mobile and

concentrated in Fig. 4. Nutria dropping in relation to a

2-inch (5.1-cm) camera lens cover. Note longitudinal

grooves major ditches and other large bodies of along

the length of the dropping. water.

Nutria are best controlled

where they are causing damage or where they are most

active. Baiting is sometimes used to concentrate nutria

in specific locations where they can be controlled more

easily. After the main concentrations of nutria are

removed, control efforts should be directed at removing

wary individuals.

Exclusion

Fences, walls,

and other structures can reduce nutria damage, but high

costs usually limit their use. As a general rule,

barriers are too expensive to be used to control damage

to agricultural crops. Low fences (about 4 feet [1.2 m])

with an apron buried at least 6 inches (15 cm) have been

used effectively to exclude nutria from home gardens and

lawns. Sheet metal shields can be used to prevent

gnawing damage to wooden and styrofoam structures and

trees. Barriers constructed of sheet metal can be

expensive to erect and unsightly.

Protect baldcypress and

other seedlings with hardware cloth tubes around

individual plants or wire mesh fencing around the

perimeter of a stand. Extensive use of these is neither

practical nor cost-effective. Plastic seedling

protectors are not effective in controlling damage to

baldcypress seedlings because nutria can chew through

them.

Sheet piling, bulkheads,

and riprap can effectively protect stream banks from

burrowing nutria. Installation requires heavy equipment

and is expensive. Use is usually restricted to

industrial or commercial applications.

Cultural Methods and

Habitat Modification

Land that is

well-drained and free of dense, weedy vegetation is

generally unattractive to nutria. Use of other good

farming practices, such as precision land leveling and

weed management, can minimize nutria damage in

agricultural areas.

Draining and Grading.

Any drainage that holds water can be used by nutria as a

travel route or home site. Consequently, eliminate

standing water in drainages to reduce their

attractiveness to nutria. This may be extremely

difficult or impossible to accomplish in low-lying areas

near coastal marshes and permanent bodies of water.

Higher sites, such as those used for growing sugarcane

and other crops, are better suited for this type of

management.

On poorly drained soils,

contour small ditches to eliminate low spots and sills

and enhance rapid drainage. Use precision leveling on

well-drained soils to eliminate small ditches that are

occasionally used by nutria.

Grading and bulldozing can

destroy active burrows in the banks of steep-sided

ditches and waterways. In addition, contour bank slopes

at less than 45o to discourage new burrowing. Sculpting

rice field levees to make them gently sloping is

similarly effective. Continued deep plowing of land

undermined by nutria can destroy shallow burrow systems

and discourage new burrowing activity.

Vegetation Control.

Eliminate brush, trees, thickets, and weeds from fence

lines and turn rows that are adjacent to ditches,

drainages, waterways, and other wetlands to discourage

nutria. Burn or remove cleared vegetation from the site.

Brush piles left on the ground or in low spots can

become ideal summer homes for nutria.

Water Level

Manipulation. Many low-lying areas along the Gulf

Coast are protected by flood control levees and pumps

that can be used to manipulate water levels. By dropping

water levels during the summer, stressful drought

conditions that cause nutria to concentrate in the

remaining aquatic habitat can be simulated, thus

increasing competition for food and space, exposure to

predators, and emigration to other suitable habitat.

Raising water levels in winter will force nutria out of

their burrows and expose them to the additional stresses

of cold weather. Water level manipulation is expensive

to implement and has not yet been proven to be

effective. Nevertheless, this method should be

considered when a comprehensive nutria control program

is being developed.

Other Cultural Methods.

Alternate field and garden sites should be considered in

areas where nutria damage has occurred on a regular

basis. New fields, gardens, and slab-on-grade buildings

should be located as far as possible from drainages,

waterways, and other water bodies where nutria live.

Late-planted baldcypress

seedlings are less susceptible to damage by nutria than

those planted in the spring. For this reason, plant

unprotected seedlings in the early fall when alternative

natural foods are readily available.

Frightening

Nutria are wary

creatures and will try to escape when threatened. Loud

noises, high pressure water sprays, and other types of

harassment have been used to scare nutria from lawns and

golf courses. The success of this type of control is

usually short-lived and problem animals soon return.

Consequently, frightening as a control technique is

neither practical nor effective.

Repellents

No chemical

repellents for nutria are currently registered. Other

rodent repellents (such as Thiram) may repel nutria, but

their effectiveness has not been determined. Use of

these without the proper state and federal pesticide

registrations is illegal.

Toxicants

Zinc Phosphide.

Zinc phospide is the only toxicant that is registered

for controlling nutria. Zinc phosphide is a Restricted

Use Pesticide that can only be purchased and applied by

certified pesticide applicators or individuals under

their direct supervision. It is a grayish-black powder

with a heavy garlic-like smell and is widely used for

controlling a variety of rodents. When used properly,

zinc phosphide poses little hazard to nontarget species,

humans, pets, or livestock.

Zinc phosphide

is highly toxic to wildlife and humans, so all

precautions and instructions on the product label should

be carefully reviewed, understood, and followed

precisely. Use an approved respirator and wear

elbow-length rubber gloves when handling this chemical

to prevent accidental poisoning. Mix and store baits

treated with zinc phosphide only in well-ventilated

areas to reduce exposing humans to chemical fumes and

dust. When possible, mix zinc phosphide at the baiting

site to avoid having to store and transport treated

baits. Never transport mixed bait or open zinc phosphide

containers in the cab of any vehicle. Store unused zinc

phosphide in a dry place in its original watertight

container because moisture causes it to deteriorate.

Immediately wash off any zinc phosphide that gets on the

skin.

Past studies have shown

that zinc phosphide can kill over 95% of the nutria

present along waterways when applied to fresh baits at a

0.75% (7,500 ppm) rate. Today, the use of zinc phosphide

at this concentration is illegal. Federal and state

registrations, however, allow lower rates to be used.

For example, the label held by USDA-APHIS-ADC (EPA Reg.

No. 56228-9) allows for a maximum 0.67% (6,700 ppm)

treatment rate. At this rate, approximately 94 pounds

(42.7 kg) of bait can be treated with 1 pound (0.4 kg)

of 63.2% zinc phosphide concentrate.

Where to Bait.

The best places to bait nutria are in waterways, ponds,

and ditches where permanent standing water and recent

nutria sign are found. Baiting in these areas increases

efficiency and reduces the likelihood that nontarget

animals will be affected. Small chunks of unpeeled

carrots, sweet potatoes, watermelon rind, and apples can

be used as bait.

The best baiting stations

for large waterways are floating rafts spaced 1/4 to 1/2

mile (0.4 to 0.8 km) apart throughout the damaged area.

In ponds, use one raft per 3 acres (1.2 ha). Rafts

measuring 4 feet (1.2 m) square or 4 x 8 feet (1.2 x 2.4

m) are easily made from sheets of 3/8-to 3/4-inch (1.0-

to 1.9-cm) exterior plywood and 3-inch (7.6-cm)

styrofoam flotation. Install a thin wooden strip around

the perimeter of the raft’s surface to keep bait from

rolling into the water. The raft should float 1 to 4

inches (2.5 to 10.2 cm) above the surface and should be

anchored to the bottom with a heavy weight or tied to

the shore (Fig. 5).

In small ditches or areas

where nutria densities are low, use 6-inch (15.2-cm)

square floating bait boards made of wood and styrofoam,

in lieu of rafts (Fig. 5). These can be maintained in

place with a long slender anchoring pole made of bamboo,

reed, or other suitable material that is placed through

a hole in the center of the platform. This allows the

board to move up and down as water levels change. Attach

baits to small nails driven into the surface of the

platform. Bait boards should be spaced 50 to 100 feet

(15.2 to 30.5 m) apart in areas where nutria are active.

Other natural sites

surrounded by water can also be baited for nutria. Small

islands, exposed tree stumps, floating logs, and feeding

platforms are excellent baiting sites. Avoid placing

baits on muskrat houses and beaver lodges. Baits can be

attached to trees, stumps, or other structures with

small nails and should be kept out of the water.

Baiting on the ground

should only be used when water sites are unsuitable or

lacking. Ground baiting is justified and effective when

eliminating the last few nutria in a local population.

Use care when ground baiting because baits may be

accessible to nontarget animals and humans. Place ground

baits near sites of nutria activity, such as trails and

entrances to burrows.

Prebaiting.

Prebaiting is a crucial step when using zinc phosphide

because it leads to nutria feeding at specific sites on

specific types of food (such as the baits; carrots or

sweet potatoes are preferred). Nutria tend to be

communal feeders, and if one nutria finds a new feeding

spot, other nutria in the area will also begin feeding

there.

To prebait, lightly coat

small (approximately 2-inch [5.1-cm] long) chunks of

untreated bait with corn oil. Place the bait at each

baiting station in late afternoon, and leave it

overnight. Use no more than 10 pounds (4.5 kg) of bait

per raft, 4 pieces of bait per baiting board, or 2 to 5

pieces at other sites at one time. Prebaiting should

continue at least 2 successive nights after nutria begin

feeding at a baiting site. Large (more than 1 week) gaps

in the prebaiting sequence necessitate that the process

be started over.

Observations of prebaited

sites will help you decide how the control program

should proceed. If nontarget animals are feeding at

these sites (as determined by sign or actual

observations of animals), then prebaiting should start

over at another location. Prepare and apply zinc

phosphide-treated baits when nutria become regular users

of prebaited baiting stations and nontarget animals are

not a problem.

Applying Zinc

Phosphide. Prepare zinc phosphide baits as

needed to prevent deterioration. Treated baits are

prepared in 10-pound (4.5-kg) batches (enough to treat

one raft) by using the following ingredients: 10 pounds

(4.5 kg) of bait (carrots or sweet potatoes are

preferred), prepared as for prebaiting; 1 fluid ounce or

2 tablespoons (30 ml) of corn oil; and 1.7 ounces or 7.5

tablespoons (48.2 g) of 63.2% zinc phosphide

concentrate.

To prepare treated baits,

add corn oil to the bait in a 5 gallon (18.9 l) plastic

or metal container. Stir the mixture until the bait is

lightly coated with corn oil. Sprinkle zinc phosphide

over the mixture and stir until the bait is uniformly

coated. Treated baits have a shiny black appearance and

should be dried for about 1 hour in a well-ventilated

area until the color changes to a dull gray. Properly

dried baits are weather-resistant and remain toxic until

they deteriorate. Although treated baits can survive

light rain, they should not be used when heavy rains are

expected or on open water that is subject to heavy wave

action.

The amount of untreated

bait eaten the last night of prebaiting determines how

much treated bait should be used on the first night.

When all or most of the untreated prebait is gone from

baiting stations by morning, the same amount of treated

bait is used on the stations the following night (e.g.,

up to 10 pounds [4.5 kg] per raft, 4 pieces per baiting

board, and 2 to 5 pieces at other sites). When smaller

quantities are eaten, reduce the amount of treated bait

that is used per station proportionately. When only a

few pieces of prebait on a raft are eaten, the raft

should be removed and replaced with several scattered

baiting boards.

The quantity of treated

bait eaten each treatment night is the quantity that

should be put out the following afternoon. Continue

baiting until no more bait is being taken. Most nutria

can be controlled after 4 nights of baiting. When

densities are high, control may require more time.

Post-Control

Procedures. Usually only 25% of the poisoned

nutria die where they can be found. Many nutria die in

dens, dense vegetation, and other inaccessible areas.

Carcasses of nutria killed with zinc phosphide should be

collected as soon as possible and disposed of by deep

burial or burning to prevent exposure of domestic and

wild scavengers to undigested stomach material

containing zinc phosphide. Dispose of any leftover

treated bait in accordance with label directions.

Cessation of damage is the

best indicator that zinc phosphide is controlling

problem animals. You can quantify the reduction in

nutria activity by putting out untreated bait at baiting

stations after the last application of zinc phosphide.

The amount eaten at this time is compared to the amount

of bait eaten on the last night of prebaiting.

Fumigants

Several

fumigants are registered for controlling burrowing

rodents but none are registered for use against nutria.

Some, such as aluminum phosphide, may have potential as

nutria control agents, but their efficacy has not been

scientifically demonstrated. Carbon monoxide gas pumped

into dens has reportedly been used to kill nutria, but

this method is neither practical nor legal because it is

not registered for this purpose.

Trapping

Commercial

Harvest. Damage to crops, levees, wetlands, and other

resources is minimal in areas where nutria are harvested

by commercial trappers. The commercial harvest of nutria

on private and public lands should be encouraged as part

of an overall program to manage nutria-caused damage.

Landowners may be able to obtain additional information

on nutria management, trapping, and a list of licensed

trappers in their area from their state wildlife agency.

Leghold traps.

Leghold traps are the most commonly used traps for

catching nutria. Double longspring traps, No. 11 or 2,

are preferred by most trappers; however, the No. 1 1/2

coilspring, No. 3 double longspring, or the soft-catch

fox trap can also be used effectively. Legholds are more

efficient and versatile than body-grip traps and are

highly recommended for nutria control work. Leghold

traps should be used with care to prevent injury to

children and pets.

Several ways of setting

leghold traps are effective. Set traps just under the

water where a trail enters a ditch, canal, or other body

of water. Make trail sets by placing a trap offset from

the trail’s center line so that nutria are caught by the

foot. Traps can be lightly covered with leaves or other

debris to hide them, but nutria are easily captured in

unconcealed traps.

Bait can be used to lure

nutria to leghold sets. Nutria use their teeth to pick

up large pieces of food; therefore, bait should be

placed beside, rather than inside, the trap jaws.

Leghold traps are also effective when set on floating

rafts that have been prebaited for a short period of

time.

Use drowning sets when

deep water is available. Otherwise, stake leghold traps

to the ground, or anchor them to solid objects in the

water or on land (such as floating logs, stumps, or

trees and shrubs). Nutria caught in non-drowning leghold

sets should be humanely dispatched with a shot or hard

blow to the head. Nontarget animals should be released.

Live Traps.

Nutria are easily captured in single-or double-door live

traps that measure 9 x 9 x 32 inches (22.8 x 22.8 x 81.3

cm) or larger.

Use these when leghold and

body-grip traps cannot be set or when animals are to be

translocated. Bait live traps with sweet potatoes and

carrots and place them along active trails or wherever

nutria or their sign are seen. A short line of baits

leading to the entrance of a live trap will increase

capture success. Live traps placed on floating rafts

will effectively catch nutria but prebaiting is

necessary. A large raft can hold up to 8 traps. Unwanted

nutria should be destroyed with a shot or blow to the

head. Nontarget animals should be released.

Floating, drop-door live

traps catch nutria but are bulky and cumbersome to use.

The same is true for expensive suitcase-type beaver

traps. Unwary nutria can be captured using a

long-handled dip net. This method should only be used by

trained damage control professionals who should take

special precautions to prevent being bitten or clawed

(Fig. 6). Live nutria can be immobilized with an

injection of ketamine hydrochloride. Funnel traps are

not effective for controlling nutria.

Body-gripping Traps.

The Conibear® trap, No. 220-2, is the most commonly used

body-gripping trap for controlling nutria. Nos. 160-2

and 330-2 Conibear® traps can also be used. Place sets

in trails, at den entrances, in culverts, and in narrow

waterways. Large body-grip traps can be dangerous and

should be handled with extreme caution. These traps

should not be set in areas frequented by children, pets,

or desirable wildlife species.

Other Traps.

Use locking snares to catch nutria when other traps

cannot be set. Snares are relatively easy to set, safer

than leghold and body-grip traps, and almost invisible

to the casual observer. Snares constructed with

3/32-inch (0.2-cm) diameter, flexible (7 x 7-winding)

stainless steel or galvanized aircraft cable are

suitable for catching nutria. Ready-made snares and

components (for example, cable, one-way cable locks,

swivels, and cable stops) for making homemade snares can

be purchased from trapping suppliers.

Place set snares in trails

and other travel routes, feeding lanes, trails, and bank

slides. Snares do not kill the animals they catch, so

anchor the snare securely. Check snares frequently

because they are often knocked down by nutria and other

animals. Snared nutria should be dispatched with a shot

or blow to the head. Release any nontarget animals that

are captured.

Shooting

Shooting can be

used as the primary method of nutria control or to

supplement other control techniques. Shooting is most

effective when done at night with a spotlight, however,

night shooting is illegal in many states and should not

be done until proper permits have been obtained. Once

shooting has been approved by the proper authorities,

nutria can be shot from the banks of waterways and other

bodies of water or from boats. In some cases, 80% of the

nutria in an area can be removed by shooting with a

shotgun or small caliber rifle, such as the .22 rimfire.

Care should be taken when shooting over open water to

prevent bullets from ricocheting.

Shooting at Bait

Stations. Baits can attract large numbers of

nutria to floating rafts, baiting boards, and other

areas where they can be shot. Shooting from dusk to

about 10:00 p.m. for 3 consecutive nights is effective

once a regular feeding pattern has been established.

Feeding sites should be lit continuously by a spotlight

and easily visible to the shooter from a vehicle or

other stationary blind. At night, nutria can be located

by their red-shining eyes and the V-shaped wake left by

swimming animals. As many as 4 to 5 nutria per hour may

be taken by this method. Shooters should wait 2 to 3

weeks before shooting nutria at the same site again.

Boat Shooting.

Shooting can also be done in the late afternoon or early

evening from a small boat paddled slowly along waterways

and large ditches or along the shores of small lakes and

ponds. Nutria are especially vulnerable to this method

when water levels are extremely high or vegetative cover

is scarce. At times, animals can be stimulated to

vocalize or decoyed to a boat or blind by making a “maw”

call, which imitates the nutria’s nocturnal feeding and

assembly call. This call can be learned from someone who

knows it or by listening to nutria vocalizations at

night. Nutria become wary quickly, so limit shooting to

no more than 3 nights, followed by 2 to 3 weeks of no

activity.

Bank Shooting.

Nutria can be shot by slowly stalking along the banks of

ditches and levees; this can be an effective control

method where nutria have not been previously harassed.

Unlike night shooting from a boat or blind, bank

shooting is most effective at twilight, both in the

evening and morning. Several nutria can usually be shot

the first night, however, success decreases with each

successive night of shooting. Daytime shooting from the

bank of a waterway is effective in some situations.

Economics

of Damage and Control

Nutria can have either

positive or negative values. They are economically

important furbearers when their pelts provide income to

commercial trappers. Conversely, they are considered

pests when they damage property.

From 1977 to 1984, an

average of 1.3 million nutria pelts were harvested

annually in the United States. Based on prices paid to

Louisiana trappers during this period, these pelts were

worth about $7.3 million.

The estimated value of

sugarcane and rice damaged by nutria each year has

ranged from several thousand dollars to over a million

dollars. If losses of other resources are added to this

amount, the estimated average loss would probably exceed

$1 million annually.

Management plans developed

for nutria should be comprehensive and should consider

the needs of all stakeholders. Regulated commercial

trapping should be an integral part of any management

scheme because it can provide continuous, long-term

income to trappers; maintain acceptable nutria

densities; and reduce damage to tolerable levels.

The value of the protected

resource must be compared with the cost of control when

determining whether nutria control is economically

feasible. Most people will not control nutria if costs

exceed the value of the resource being protected or if

control will adversely impact income derived from

trapping. Of course, there are exceptions, especially

when the resource has a high sentimental or aesthetic

value to the owner or user.

Acknowledgments

This chapter is a revision

of an earlier chapter written by Evans (1983). Kinler et

al. (1987) and Willner (1982) were the primary sources

consulted for biological information on nutria.

Figures 1 and 3 by Peggy

A. Duhon of Lafayette, Louisiana.

Figure 2 from Willner

(1982) and reprinted with permission of The Johns

Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Harland D. Guillory, Dr.

Robert B. Hamilton, and E. Allen Wilson reviewed the

manuscript and provided valuable comments and

suggestions.

For Additional Information

Baker, S. J., and C. N. Clarke. 1988. Cage trapping

coypus (Myocastor coypus) on baited rafts. J. Appl.

Ecol. 25:41-48.

Conner, W. H., and J. R.

Toliver. 1987. The problem of planting cypress in

Louisiana swamplands when nutria (Myocastor coypus) are

present. Proc. Eastern Wildl. Damage Control Conf.

3:42-49.

Conner, W. H., and J. R.

Toliver. 1987. Vexar seedling protectors did not reduce

nutria damage to planted baldcypress seedlings. Tree

Planters’ Notes 38:26-29.

Evans, J. 1970. About

nutria and their control. US Dep. Inter., Bureau Sport

Fish. Wildl., Resour. Publ. No. 86. 65 pp.

Evans, J. 1983. Nutria.

Pages B-61 to B-70 in R.M. Timm, ed. Prevention and

control of wildlife damage, Coop. Ext. Serv., Univ.

Nebraska, Lincoln.

Evans, J., J. O. Ells, R.

D. Nass, and A. L. Ward. 1972. Techniques for capturing,

handling, and marking nutria. Trans. Annual Conf.

Southeast. Assoc. Game Fish Comm. 25:295-315.

Falke, J. 1988.

Controlling nutria damage. Texas An. Damage Control Serv.

Leaflet 1918. 3 pp.

Kinler, N. W., G.

Linscombe, and P. R. Ramsey. 1987. Nutria. Pages 331-343

in M. Novak, J. A. Baker, M. F. Obbard, and B. Malloch,

eds. Wild furbearer management and conservation in North

America. Ministry of Natural Resources, Ontario.

Wade, D. A., and C. W.

Ramsey. 1986. Identifying and managing aquatic rodents

in Texas: beaver, nutria, and muskrats. Texas Agric.

Ext. Serv. Bull. 1556. 46 pp.

Willner, G. R. 1982.

Nutria. Pages 1059-1076 in J. A. Chapman and G. A.

Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North America: biology,

management, and economics. The Johns Hopkins Univ.

Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|