|

|

|

|

|

RODENTS: Mountain Beavers |

|

|

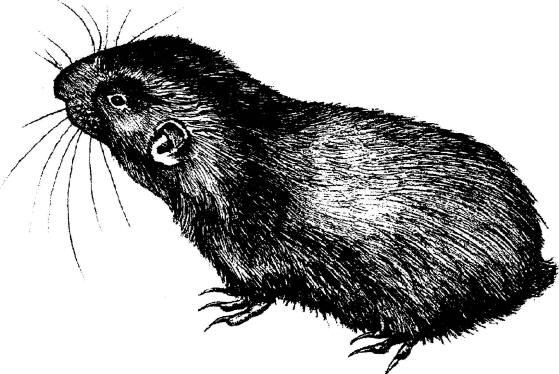

Fig. 1. Mountain beaver,

Aplodontia rufa

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

-

Exclusion

-

Use plastic mesh

seedling protectors on small tree seedlings. Wire

mesh cages are somewhat effective, but large

diameter cages are expensive and allow animals to

enter them.

-

Exclusion from large

areas with buried fencing is impractical for most

sites.

-

Cultural

Methods/Habitat Modification

-

Plant large tree

seedlings that will tolerate minor damage.

-

Burn or remove slash

to reduce cover.

-

Tractor scarification

of sites will destroy burrow systems.

-

Remove underground

nests to reduce reinvasion.

-

Frightening

-

Not applicable.

-

Repellents

-

36% Big Game Repellent

Powder has been registered for mountain beaver in

Washington and Oregon.

-

Toxicants

-

A pelleted strychnine

alkaloid bait was registered in Oregon but may be

discontinued.

-

Fumigants

-

None are registered.

-

Trapping

-

No. 110 Conibear®

traps placed in main burrows are effective but may

take nontarget animals using burrows, including

predators.

-

Welded-wire,

double-door live traps are effective and selective,

but are primarily useful for research studies and

removal of animals in urban/ residential situations.

-

Shooting

-

Not applicable.

Identification Identification

The mountain beaver (Aplodontia

rufa, Fig. 1) is a medium-sized rodent in the family

Aplodontiadae. There are no other species in the family.

Average adults weigh 2.3 pounds (1,050 g) and range from

1.8 to 3.5 pounds (800 to 1,600 g). Average overall

length is 13.5 inches (34 cm), including a rudimentary

tail about 1 inch (2.5 cm) long. The body is stout and

compact. The head is relatively large and wide and

blends into a large neck with no depression where it

joins the shoulders. The eyes and ears are relatively

small and the cheeks have long silver “whiskers.” The

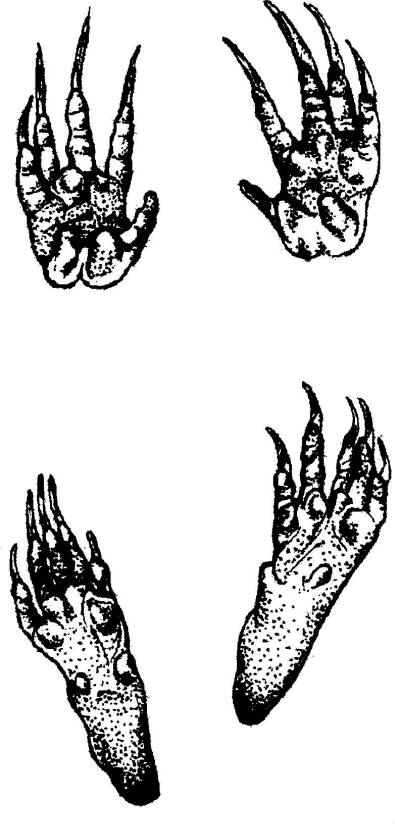

hind feet are about 2 inches (5 cm) long and slightly

longer than the front feet (Fig. 2). Mountain beavers

often balance on their hind feet while feeding. The

front feet are developed for grasping and climbing.

Adults are grayish brown

or reddish brown. The underfur on the back and sides is

charcoal with brown tips; guard hair is dark brown or

black with silver tips. Ventrally, the underfur is gray

with few guard hairs. A whitish spot of bare skin is

present at the base of the ears. The feet are lightly

furred on top and bare on the soles. Young animals are

generally darker than adults. Males have a baculum (a

bone about 1 inch [2.5 cm] long in the penis). Mature

females generally have a patch of dark-colored underfur

around each of the six nipples.

Fig. 2. Mountain beaver

feet are developed for burrowing and climbing.

Range

Mountain beavers are found

in the Pacific coastal region from southern British

Columbia to northern California (Fig. 3). They range

westward from the Cascade Mountains and southward into

the Sierras. Numbers are higher and populations are more

Mountains and in the coast range of Washington and

Oregon than elsewhere. In the southern limit of its

range, populations are more scattered but sometimes

locally abundant.

Habitat

Mountain beaver habitat is

characteristically dominated by coastal Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga

menziesii) and western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla).

Within this zone, mountain beavers often favor moist

ravines and wooded or brushy hillsides or flats that are

not subjected to continuous flooding. Although

frequently found near small streams, they are not

limited to those sites except in more arid regions.

Active burrows may carry water runoff after heavy rains,

but mountain beavers will vacate burrow systems that

become flooded. Mountain beavers do not require free

water; they obtain adequate moisture from the vegetation

they eat.

Mountain beavers occupy

mature forests usually in openings or in thinned stands

where there is substantial vegetation in the understory.

They usually leave stands where the canopy has closed

and ground vegetation has become sparse. Preferred

habitats in forested sites are often dominated by red

alder (Alnus rubra), which the animals promote by

preferentially feeding on conifers and other vegetation.

These sites are often dominated by an understory of

sword fern (Polystichum munitum), a preferred food of

mountain beavers. Stands of bracken fern (Pteridium

aquilinum) are also favored by mountain beavers.

Preferred shrub habitats include salmonberry (Rubus

spectabilis), huckleberry (Vaccinium parvifolium), salal

(Gaultheria shallon), and Oregon grape (Berberis

nervosa). Small trees often found cut by mountain

beavers include vine maple (Acer circinatum) and cascara

(Rhamnus purshiana). These species are often

intermingled with 30 or more other plant species

including forbs, grasses, and sedges.

Food Habits

The food habits of

mountain beavers are closely tied to the dominant

vegetation in their habitat. Sword fern and bracken fern

are preferred when available. Douglas-fir, hemlock,

western red cedar (Thuja plicata), and red alder are all

commercial tree species that are cut and eaten by

mountain beavers. Other species found in their habitat

are either eaten or used for construction of nests. Most

feeding occurs above ground within 50 feet (15.2 m) of

burrows, although occasionally mountain beavers may

travel several hundred feet from burrows. They routinely

climb shrubs and trees 8 feet (2.4 m) or higher to cut

off branches up to 3/4 inch (1.9 cm) in diameter, where

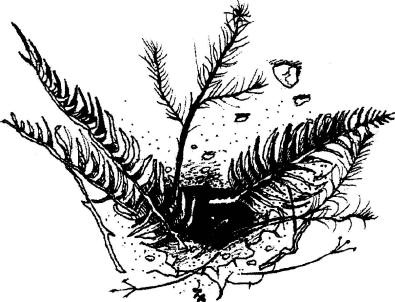

they leave cut stubs of branches on trees. Mountain

beavers also girdle the base of tree stems and will feed

on stems up to 6 inches (15 cm) in diameter, as well as

the root systems of large trees. The bark is found in

the stomach contents of animals collected in midwinter.

Woody stems are often girdled and cut into about 6-inch

(15-cm) lengths. Food and/or nest items are often

stacked at burrow entrances (Fig. 4) but are sometimes

carried directly to food caches or nests. Plant material

is occasionally eaten outside the burrow but is usually

eaten at the food cache, in nests, or in the burrow.

Mountain beavers practice coprophagy (consumption of

feces) and select soft over continuous in the coastal

Olympic hard pellets.

Fig. 4. Sword fern and

Douglas-fir piled at the entrance of a mountain beaver

burrow.

General

Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior General

Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Mountain beavers dig

extensive individual burrow systems that generally are

1/2 to 6 feet (0.2 to 1.8 m) deep with 10 to 30 exit or

entrance holes that are usually left open. The ground

surface often caves in where burrows are shallow. There

are many exit burrows forming T-shaped junctions with a

main burrow. These exits may be horizontal or even

vertical. Burrows are often found under old logs and are

sometimes on the surface in logging debris. Mountain

beavers seldom make obvious trails through vegetation.

Most activity is at night and surface travel is usually

near their burrows. Sometimes they are seen during

daylight in dense surface vegetation several feet from

burrow openings. Burrow systems usually cover a 1/4 acre

(0.1 ha) or more and may intersect with burrow systems

of adjacent individuals. Each system is apparently

defended against neighboring mountain beavers. When an

animal leaves a system or dies, the system is often

quickly reoccupied by another mountain beaver.

Fig. 5. Cross section of

part of a mountain beaver burrow system including food

cache, nest, and fecal chamber.

In the spring and summer,

mountain beavers periodically remove molded and

partially eaten vegetation from their food caches. Most

soil excavation occurs during dry periods from spring to

fall. Vegetation is cut year-round, but activity outside

burrows and away from the nest is curtailed during

subfreezing temperatures. Portions of a burrow may not

be used daily, but active burrows in a burrow system are

usually used at least weekly.

The habit of stacking cut

vegetation at burrow openings has been considered a

means to lower its moisture content before taking it

into humid food caches or relatively dry nest chambers.

Mountain beavers, however, do not always stack cut

vegetation and often cut it during periods of continuous

rainfall and high humidity. Occasionally there may be 20

or 30 fern fronds or several tree seedlings stacked at

burrow openings. The animals usually are quick to carry

away small bundles of sword fern that they have placed

inside the burrow opening. Some items such as grasses

and trailing blackberry vines are cut but are seldom

stacked at openings.

Little is known about

mountain beaver behavior during the breeding season.

Breeding activity occurs mainly from January to March

with gestation lasting about 30 days. Young are born

blind and hairless, weighing about 3/4 ounce (20 g).

They develop incisors at about 30 days and are weaned at

about 8 weeks. Young animals are often active in May.

Females apparently do not bear young until 2 years of

age.

Territorial behavior

usually limits mountain beaver population densities to

about 4 per acre (10/ha) although densities may be

higher in some areas. Densities are generally higher in

May and June when young are still active within burrow

systems. In winter, average population densities in

large reforestation tracts (more than 100 acres [40 ha])

seldom exceed 2 animals per acre (5/ha).

Several predators prey on

mountain beavers. Above ground, the main predator, when

present, is probably the bobcat (Felis rufus). Coyotes (Canis

latrans) and great horned owls (Bubo virginianus) are

other major large predators. In burrow systems, mink (Mustela

vison) and long-tailed weasels (Mustela frenata) are the

main predators. Weasel predation is probably limited to

young or subadult animals less able to defend

themselves.

Mountain beavers appear

relatively free of diseases and internal parasites.

Animals in western Washington were checked as possible

carriers of plague but were found negative. A large flea

(Hystrichopsylla schefferi) unique to mountain beavers

is common on the animals but is not known to be a

problem for humans. Mites (Acarina spp.) often infest

the ear and eye region.

Damage and Damage Identification

Mountain beavers have

damaged an estimated 300,000 acres (120,000 ha) of

commercial coniferous tree species in western Washington

and Oregon. Much of the affected land has the potential

to produce timber values of over $10,000 an acre. The

damage period extends to about 20 years after planting.

The major losses occur from cutting tree seedlings

during the first year after planting (Fig. 6). Secondary

damage occurs during the next 5 years to surviving tree

seedlings, followed by stem girdling and root damage for

the next 10 to 20 years. Increased need for weed and

brush control and occasional replanting costs add to the

economic losses caused by mountain beavers.

Damage

to conifer seedlings is identified by angular rough cuts

on stems 1/4 to 3/4 inches (0.6 to 1.9 cm) in diameter.

Mountain beavers climb larger trees and cut stems near

the tips. Limbs are often cut a few inches from the

stem. Small trees are usually cut near ground level

while others may be cut several feet up the stem.

Seedling damage occurs primarily in winter and early

spring, but often continues throughout the year. Damage

to conifer seedlings is identified by angular rough cuts

on stems 1/4 to 3/4 inches (0.6 to 1.9 cm) in diameter.

Mountain beavers climb larger trees and cut stems near

the tips. Limbs are often cut a few inches from the

stem. Small trees are usually cut near ground level

while others may be cut several feet up the stem.

Seedling damage occurs primarily in winter and early

spring, but often continues throughout the year.

Fig. 6. Mountain beaver in

feeding position.

Most stem-girdling damage

is at the base of 3- to 6-inch (7- to 15-cm) diameter

stems (Fig. 7). Girdling damage can be distinguished

from that caused by bears or porcupines in that mountain

beavers do not leave pieces of bark scattered on the

ground and they cut the bark smoothly along the edges.

Girdling damage to older stems is more difficult to

distinguish, but it can be verified by examining burrows

near tree trunks where fresh girdling can be seen on the

roots.

Root girdling may occur at

any age, but small roots are usually cut instead of

girdled. Trees with stems over 6 inches (15 cm) in

diameter may die due to extreme root girdling. Root

girdling may allow tree root pathogens to become

established in individual trees and spread to other

trees. It occurs in winter and spring, and may occur in

other seasons.

Fig. 7. Mountain

beaver–girdled conifer tree.

Damage to coniferous

species is considered detrimental to forest production

and can have long-term effects on habitats. This damage

to commercial crops and other vegetation, however, does

provide diversity of cover for other wildlife. In one

area on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington, the

excessive damage to conifers by mountain beavers caused

a manager to change the area designation from

reforestation land to wildlife habitat.

Legal

Status

Fig. 8. Plastic mesh

seedling protector.

Plastic mesh seedling

protectors photodegrade and deteriorate after several

years. Although they expand with stem growth, they

probably provide little protection from girdling of

large diameter stems by mountain beavers.

Wire mesh cages 1 to 3

feet (0.3 to 1 m) in diameter will protect individual

trees but are expensive and may be climbed over and

burrowed under. These cages also allow competing

vegetation to be protected and often cause poor tree

growth. The wire used in these cages may injure tree

growth if cages are tipped or come into contact with the

tree stem.

Cultural Methods

Plant large

tree seedlings to improve survival of the trees in sites

occupied by mountain beavers. Larger stems are less

subject to being clipped at ground level. Although large

seedlings may be seriously damaged, enough foliage often

remains after damage to provide for regrowth and

survival after later damage. Damage-resistant trees

should be about 2 feet (0.6 m) tall and have 1/2-inch

(1.3-cm) or larger diameter stems at the base. Trees

should be planted away from burrow openings so that

mountain beavers will find them less convenient to cut.

Prescribed slash burning

before planting may reduce mountain beaver populations

by reducing available forage and increasing predation.

Extremely hot fires may cause some mortality, but most

mountain beavers will remain protected in their burrows.

Reduction in available forage after fire may cause

mountain beavers to travel farther from burrows and

subject them to higher levels of predation. Legal

restrictions or other practices that inhibit prescribed

burning may favor mountain beaver populations.

Mountain beaver burrow

systems may be destroyed by tractor scarification on

level or moderate slopes when done to remove logging

debris for replanting or to convert brush fields to

plantations. This method requires the use of toothed

land clearing blades to rip soil and destroy burrows. It

seldom removes the deeper nest chambers but can make the

area unattractive to mountain beavers. Avoid piling soil

and wood debris, both of which will attract mountain

beavers. Wood debris piles should be burned when

possible and soil leveled.

Removal of nest chambers

after population reduction will reduce reinvasion of the

burrow systems by 50% or more. Practical methods for

locating and removing nest chambers need further study.

Fig. 9. Application of

powdered repellent to conifer seedling.

Repellents

Coniferous

seedlings subject to mountain beaver damage may be

treated with repellents, but they require special

application procedures to assure the plant stem is

treated near the base (Fig. 9). The effectiveness of a

repellent can be enhanced by conditioning the mountain

beavers to the repellent. Treat cull seedlings with the

same repellent and place them in active burrows. This

practice has caused mountain beavers to avoid both

treated and untreated planted seedlings for up to a year

after planting. The only repellent that has been

registered for mountain beavers in Washington and Oregon

is 36% Big Game Repellent Powder (BGR-P ), originally

registered only for big game. Thiram (tetramethylthiuram

disulfide) is another repellent registered for hares,

rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.), and big game that has been

effective against mountain beavers. Repellents may be of

most value where they cause a long-term avoidance. The

placement of repellent-treated cull tree seedlings in

burrows at time of planting and treating significantly

improves repellent efficacy.

Toxicants

A pelleted

0.31% strychnine bait (Boomer-Rid®) has been registered

in Oregon for control of mountain beavers. Recent field

tests in Washington and Oregon, however, showed marginal

efficacy in late winter with Boomer-Rid®. Pelleted bait

is placed by hand inside main burrows, using about five

baits each in 10 burrow openings in each system. The

registered label allows 1/2 to 1 1/2 pounds of bait per

acre (0.6 to 1.7 kg/ha). The bait formulation contains

waterproofing binders that tolerate wet burrow

conditions.

Experimental zinc

phosphide-treated apple bait was poorly accepted by

mountain beavers and was potentially hazardous to bait

handlers. The treated bait was readily eaten by

black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus) and

could present a hazard.

Baiting is severely

restricted in areas frequented by endangered species

such as northern spotted owls (Strix occidentalis

caurina), and bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus).

Fumigants

Fumigants are

generally ineffective because of the open,

well-ventilated structure of the mountain beaver burrow

systems. Aluminum phosphide that was activated when

mountain beavers pulled pellets attached to vegetation

into the nest area was only partially effective. The use

of carbon monoxide gas cartridges and carbon monoxide

gas have been unsuccessful in controlling mountain

beavers. No fumigants are registered for mountain beaver

control. The use of smoke bombs or similar material is

effective in locating the numerous openings in a

mountain beaver burrow system.

Trapping

Mountain

beavers are routinely kill trapped for damage control on

many forest lands scheduled for planting. Trapping is

usually done just prior to planting and repeated 1 or 2

years afterward. Trapping is also repeated when damage

is found in established plantations. Set kill traps in

older stands where stems and roots are being girdled and

undermined. Live trapping is seldom done in forest lands

except for research purposes, but it is used where there

are urban damage problems.

Kill trapping is normally

done using unbaited Conibear® No. 110 traps set in main

burrows. Anchor traps with three sticks, with either two

in the spring (Fig. 10) or with one in the spring and

one at the far end of the jaws, in a vertical position

with the trigger hanging. The trap should take up most

of the space in the burrow, and when properly anchored,

is readily entered by the mountain beavers. This trap is

sometimes not immediately lethal because of the mountain

beaver’s thick short neck. Stronger double-spring traps

may be more effective, but are more difficult to set in

the limited burrow space.

Teams of trappers are

normally used when trapping large acreages. Individual

trappers should be spaced about 30 to 50 feet (9.1 to

15.2 m) apart, depending on habitat conditions. Extra

searching may be required in areas with many small

drainages that may have many burrows. Active burrows

have fresh soil and vegetation piled at burrow entrances

or in burrows. Burrows can often be visually inspected

through openings to determine if there is recent use.

Set two or three traps in each active burrow system. All

trap sites should be marked with flags and mapped so

they may be relocated; a crew of trappers should use

several colors of flagging so that individuals can

relocate their own traplines by color. Trapping in older

stands of conifers can be very difficult because traps

are not easily relocated when branches hide the

flagging. Mapping and flagging travel routes in this

type of habitat may be necessary. The trap lines are

usually checked after 1 day and again checked and pulled

after about 5 days. Traps are usually reset during the

first check even where mountain beavers are captured,

because the systems may be quickly invaded by other

mountain beavers. If trapping is unsuccessful, move

traps to burrows with fresh activity. During the

breeding season (January to March), male mountain

beavers may be more commonly trapped than females

because of their greater activity.

During subfreezing

temperatures, trapping should be postponed or trapping

periods lengthened to include warmer periods when

mountain beavers are more active. Trapping during

periods of snow is also usually less successful than

during snow-free periods because trap sites are

difficult to locate and set, and animals are less

active.

Trapping may take

nontarget species such as weasels, spotted skunks (Spilogale

putorius), mink, squirrels (Tamiasciurus spp.), rabbits,

and hares that use the mountain beaver burrows.

Nontarget losses may be reduced by positioning the trap

trigger near the side of the trap so that it is less

likely to be tripped when small animals pass through.

Live trapping is

recommended where domestic animals may enter the

burrows. Double-door wire mesh live traps such as

Tomahawk traps (6 x 6 x 24 inches [15 x 15 x 61 cm])

should be set nearly level in main burrows. Suitable

vegetation should be placed inside and along the outside

of the trap. Wrap the trap with black plastic and cover

it with soil to protect animals from the weather.

Placement should assure that animals enter rather than

go around the ends of the trap. Traps must be checked

once or twice daily, preferably in early morning and

again in the late afternoon, to minimize injury and

stress to mountain beavers held in the live traps.

Live-captured mountain beavers should be placed in dry

burlap sacks and, if necessary, euthanized with carbon

dioxide.

Shooting

Shooting is not

a practical control method.

Other Methods

Habitat

manipulation by increasing or decreasing favored

vegetation has been evaluated only indirectly. Where

native forbs were seeded to reduce deer damage to

Douglas-fir plantations, mountain beaver damage did not

significantly decrease or increase. In another area,

where red huckleberry was abundant and extensively cut,

mountain beaver damage to Douglas-fir was insignificant.

Economics of Damage and Control

Mountain beavers cause

considerable economic damage to reforestation. Most of

their habitat is in timberland where the potential crop

value is high. Well-stocked stands of Douglas-fir are

usually commercially thinned once or twice before final

harvest, and often produce timber values of thousands of

dollars per acre. When mountain beavers prevent

reforestation or cause expenditures for protecting

reforestation, the value of the crops is reduced or

eliminated. A planned Douglas-fir crop rotation period

of 40 years on good sites can be severely disrupted if

at 15 years the crop is lost to damage by mountain

beavers. Since mountain beaver damage occurs on about

300,000 acres (120,000 ha) of commercial forest land, a

conservative annual loss estimate of $100 per acre

($250/ ha) results in an annual loss of $30 million.

Losses to mountain beavers may be $10,000 per acre

($24,700/ha) when damage causes failure of the timber

crop.

Economic losses are caused

by both direct and indirect damage. Cutting of planted

tree seedlings is the most common damage. If it has been

several years since planting, the site may need brush

control by machine, hand, or herbicide before replanting

can be done. Damage to tree seedlings also keeps the

trees within a size range that is susceptible to damage

by hares, rabbits, deer, and elk. If damage is not

controlled, large areas may not be adequately

reforested. Trees that escape early damage may be

damaged later by girdling and undermining by mountain

beavers, causing a loss of many years’ growth of

commercially valuable species.

The mountain beaver

currently has no commercial value. The pelt has no fur

value and there is no market for the meat. The animal is

of significant zoological and medical interest, however,

because of its limited range and unique physiological

characteristics. Despite its limited range, however, the

overall populations of mountain beavers have probably

increased since timber harvesting began in the Pacific

Northwest.

The burrowing and

vegetation cutting activities of mountain beavers may

improve soils and reduce competition by brush species.

Sometimes, however, the burrowing activity has caused

damage to roads and trails. Forest workers are

periodically injured by falling into mountain beaver

burrows.

An economic study of

Pacific Northwest forest animal damage indicates that

damage control expenditures of about $150 per acre

($375/ha) are reasonable on average-site Douglas-fir

forest land. On higher quality land the expenditure for

damage control can be higher, particularly where

mountain beavers cause heavy mortality in reforestation

areas.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank numerous

employees of USDAAPHIS, the USDA Forest Service, the

USDI Bureau of Land Management, the Washington

Department of Natural Resources, the Oregon Department

of Forestry, and many private forest industry companies

for support of studies involving research into mountain

beaver damage control. I also wish to thank Kathryn

Campbell for the illustrations drawn from photos and

descriptions by the author.

For Additional Information

Borrecco, J. E. 1976. Vexar tubing as a means to protect

seedlings from wildlife damage. Weyerhaeuser For. Res.

Tech. Rep. 4101/76/36. 18 pp.

Borrecco, J. E., and R. J.

Anderson. 1980. Mountain beaver problems in the forests

of California, Oregon, and Washington. Proc. Vertebr.

Pest Conf. 9:135-142.

Campbell, D. L. 1987.

Potential for aversive conditioning in forest animal

damage control. Pages 117-118 in H. L. Black, ed. Proc.

Symp. Anim. Damage Manage. Pacific Northwest For.

Spokane, Washington.

Campbell, D. L., and J.

Evans. 1975. “Vexar” seedling protectors to reduce

wildlife damage to Douglas-fir. USDI Fish Wildl. Serv.

Wildl. Leaflet. No. 508. 11 pp.

Campbell, D. L. and J.

Evans. 1988. Recent approaches to controlling mountain

beavers (Aplodontia rufa) in Pacific Northwest forests.

Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 13:183-187.

Campbell, D. L., J. Evans,

and G. B. Hartman. 1988. Evaluation of seedling

protection materials in western Oregon. US Dep. Inter.

Bureau Land Manage. Tech. Note OR-5. 14 pp.

Campbell, D. L., J. D.

Ocheltree, and M. G. Carey. 1988. Adaptation of mountain

beaver (Aplodontia rufa) to removal of underground

nests. Northwest Sci. 62(2):75.

Engeman, R. M., D. L.

Campbell, and J. Evans. 1991. An evaluation of two

activity indicators for use in mountain beaver burrow

systems. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 19:413-416.

Evans, J. 1984. Mountain

beaver. Pages 610-611 in P. MacDonald, ed. The

encyclopedia of mammals. Facts on File Publ. New York.

Evans, J. 1987. Mountain

beaver damage and management. Pages 73-74 in H. L.

Black, ed. Proc. Symp. Anim. Damage Manage. Pacific

Northwest For. Spokane, Washington.

Feldhamer, G. A. and J. A.

Rochelle. 1982. Mountain beaver. Pages 167-175 in J. A.

Chapman and G. A. Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North

America: biology, management, and economics. The Johns

Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore.

Hartwell, H. D. and L. E.

Johnson. 1992. Mountain beaver tree injuries in relation

to forest regeneration. DNR Res. Rep. State of

Washington, Dept. Nat. Resour. Olympia. 49 pp.

Hooven, E. F. 1977. The

mountain beaver in Oregon: its life history and control.

Res. Pap. 30. Oregon State Univ. Corvallis. 20 pp.

Martin, P. 1971. Movements

and activities of the mountain beaver (Aplodontia rufa).

J. Mammal. 52:717-723.

Motobu, D., J. Todd, and

M. Jones. 1977. Trapping guidelines for mountain beaver,

Weyerhaeuser For. Res. Rep. 042-4101/77/20. 28 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom; Robert

M. Timm; Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

05/16/2006

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|