|

|

|

|

|

RODENTS: Mice, White-Footed and Deer |

|

|

Identification

Fifteen species of native

mice of the genus Peromyscus may be found in the United

States. The two most common and widely distributed

species are the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus, Fig.

1) and the white-footed mouse (P. leucopus). This

chapter will deal primarily with these species.

Collectively, all species of Peromyscus are often

referred to as “white-footed mice” or “deer mice.” Other

species include the brush mouse (P. boylei), cactus

mouse (P. eremicus), canyon mouse (P. crinitus), cotton

mouse (P. gossypinus), golden mouse (P. nuttalli), piñon

mouse (P. truei), rock mouse (P. difficilis), white-ankled

mouse (P. pectoralis), Merriam mouse (P. merriami),

California mouse (P. californicus), Sitka mouse (P.

sitkensis), oldfield mouse (P. polionotus), and the

Florida mouse (P. floridanus).

All of the Peromyscus

species have white feet, usually white undersides, and

brownish upper surfaces. Their tails are relatively

long, sometimes as long as the head and body. The deer

mouse and some other species have a distinct separation

between the brownish back and white belly. Their tails

are also sharply bicolored. It is difficult even for an

expert to tell all of the species apart.

In comparison to house

mice, white-footed and deer mice have larger eyes and

ears. They are considered by most people to be more

“attractive” than house mice, and they do not have the

characteristic mousy odor of house mice. All species of

Peromyscus cause similar problems and require similar

solutions.

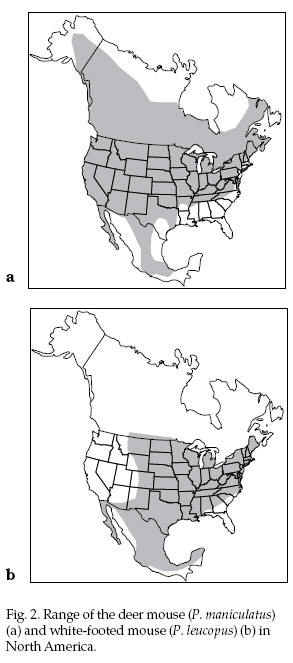

Range

The

deer mouse is found throughout most of North America

(Fig. 2). The white-footed mouse is found throughout the

United States east of the Rocky Mountains except in

parts of the Southeast (Fig. 2). The

deer mouse is found throughout most of North America

(Fig. 2). The white-footed mouse is found throughout the

United States east of the Rocky Mountains except in

parts of the Southeast (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Range of the deer

mouse (P. maniculatus) (a) and white-footed mouse (P.

leucopus) (b) in North America.

The brush mouse is found

from southwestern Missouri and northwestern Arkansas

through Oklahoma, central and western Texas, New Mexico,

southwestern Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and California.

The cactus mouse is limited to western Texas, southern

New Mexico, Arizona (except the northeast portion), and

southern California. The canyon mouse occurs in western

Colorado, northwestern New Mexico, northern and western

Arizona, Utah, Nevada, southern California, southeast

Oregon, and southwestern Idaho.

The cotton mouse is found

only in the southeastern United States from east Texas

and Arkansas through southeastern Virginia. The golden

mouse occupies a similar range but it extends slightly

farther north.

The piñon mouse is found

from southwestern California through the southwestern

United States to the Texas panhandle. The rock mouse is

limited to Colorado, southeastern Utah, eastern Arizona,

New Mexico, and the far western portion of Texas. The

white-ankled mouse is found only in parts of Texas and

small areas in southern New Mexico, southern Oklahoma,

and southern Arizona.

The Merriam mouse is

limited to areas within southern Arizona. The California

mouse ranges from San Francisco Bay to northern Baja

California, including parts of the southern San Joaquin

Valley. The Sitka mouse is found only on certain islands

of Alaska and British Columbia.

The oldfield mouse is

distributed across eastern Alabama, Georgia, South

Carolina, and Florida. The Florida mouse, as its name

indicates, is found only in Florida.

Habitat

The deer mouse occupies

nearly every type of habitat within its range, from

forests to grasslands. It is the most widely distributed

and abundant mammal in North America.

The white-footed mouse is

also widely distributed but prefers wooded or brushy

areas. It is sometimes found in open areas.

The other species of

Peromyscus have somewhat more specialized habitat

preferences. For example, the cactus mouse occurs in low

deserts with sandy soil and scattered vegetation and on

rocky outcrops. The brush mouse lives in chaparral areas

of semidesert regions, often in rocky habitats.

Food Habits

White-footed and deer mice

are primarily seed eaters. Frequently they will feed on

seeds, nuts, acorns, and other similar items that are

available. They also consume fruits, insects and insect

larvae, fungi, and possibly some green vegetation. They

often store quantities of food near their nest sites,

particularly in the fall when seeds, nuts, or acorns are

abundant.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

White-footed and deer mice

are mostly nocturnal with a home range of 1/3 acre to 4

acres (0.1 to 1.6 ha) or larger. A summer population

density may reach a high of about 15 mice per acre

(37/ha).

In warm regions,

reproduction may occur more or less year-round in some

species. More typically, breeding occurs from spring

until fall with a summer lull. This is especially true

in cooler climates. Litter size varies from 1 to 8

young, but is usually 3 to 5. Females may have from 2 to

4 or more litters per year, depending on species and

climate.

During the breeding

season, female white-footed and deer mice come into heat

every fifth day until impregnated. The gestation period

is usually 21 to 23 days, but may be as long as 37 days

in nursing females. Young are weaned when they are 2 to

3 weeks old and become sexually mature at about 7 to 8

weeks of age. Those born in spring and summer may breed

that same year.

Mated pairs usually remain

together during the breeding season but may take new

mates in the spring if both survive the winter. If one

mate dies, a new one is acquired. Family groups usually

nest together through the winter. They do not hibernate

but may become torpid for a few days when winter weather

is severe.

Nests consist of stems,

twigs, leaves, roots of grasses, and other fibrous

materials. They may be lined with fur, feathers, or

shredded cloth. The deer mouse often builds its nest

underground in cavities beneath the roots of trees or

shrubs, beneath a log or board, or in a burrow made by

another rodent. Sometimes deer mice nest in aboveground

sites such as a hollow log or fencepost, or in cupboards

and furniture of unoccupied buildings.

White-footed mice spend a

great deal of time in trees. They may use aban-locating

and digging up buried seed. Formerly, much reforestation

was attempted by direct seeding of clear-cut areas, but

seed predation by deer mice and white-footed mice, and

by other rodents and birds, caused frequent failure in

the regeneration. For this reason, to reestablish

Douglas fir and other commercial timber species today,

it is often necessary to hand-plant seedlings, despite

the increased expense of this method.

Damage and Damage Identification

The principal problem

caused by white-footed and deer mice is their tendency

to enter homes, cabins, and other structures that are

not rodent-proof. Here they build nests, store food, and

can cause considerable damage to upholstered furniture,

mattresses, clothing, paper, or other materials that

they find suitable for their nest-building activities.

Nests, droppings, and other signs left by these mice are

similar to those of house mice. White-footed and deer

mice have a greater tendency to cache food supplies,

such as acorns, seeds, or nuts, than do house mice.

White-footed and deer mice are uncommon in urban or

suburban residential areas unless there is considerable

open space (fields, parks) nearby.

Both white-footed and deer

mice occasionally dig up and consume newly planted seeds

in gardens, flowerbeds, and field borders. Their

excellent sense of smell makes them highly efficient at

locating and digging up buried seed. Formerly, much

reforestation was attempted by direct seeding of

clearcut areas, but seed predation by deer mice and

white-footed mice, and by other rodents and birds,

caused frequent failure in the regeneration. For this

reason, to reestablish Douglas fir and other commercial

timber species today, it is often necessary to handplant

seedlings, despite the increased expense of this method.

In mid-1993, the deer

mouse (P. maniculatus) was first implicated as a

potential reservoir of a type of hantavirus responsible

for an adult respiratory distress syndrome, leading to

several deaths in the Four Corners area of the United

States. Subsequent isolations of the virus thought

responsible for this illness have been made from several

Western states. The source of the disease is thought to

be through human contact with urine, feces, or saliva

from infected rodents.

Legal Status

White-footed and deer mice

are considered native, nongame mammals and receive

whatever protection may be afforded such species under

state or local laws. It is usually permissible to

control them when necessary, but first check with your

state wildlife agency. Doned bird or squirrel nests,

adding a protective “roof” of twigs and other materials

to completely enclose a bird’s nest (Fig. 3). Like deer

mice, they nest at or just below ground level or in

buildings.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Rodent-proof construction is the best and most

permanent method of preventing rodents from entering

homes, cabins, or other structures. White-footed and

deer mice require measures similar to those used for

excluding house mice. No openings larger than 1/4 inch

(0.6 cm) should be left unmodified. Mice will gnaw to

enlarge such openings so they can gain entry. For

additional information, see the chapter Rodent-proof

Construction & Exclusion Methods.

Use folded hardware cloth

(wire mesh) of 1/4 inch (0.6 cm) or smaller to protect

newly seeded garden plots. Homemade wire-screen caps or

bowls can be placed over seeded spots. Bury the edges of

the wire several inches beneath the soil. Plastic

strawberry-type baskets inverted over seeded spots serve

a similar purpose.

Habitat Modification

Store foodstuffs such as dry pet food, grass seed,

and boxed groceries left in cabins in rodent-proof

containers.

Mouse damage can be

reduced in cabins or other buildings that are used only

occasionally, by removing or limiting nesting

opportunities for mice. Remove padded cushions from

sofas and chairs and store them on edge, separate from

one another, preferably off the floor. Remove drawers in

empty cupboards or chests and reinsert them upside-down,

eliminating them as suitable nesting sites. Other such

techniques can be invented to outwit mice. Remember that

white-footed and deer mice are excellent climbers. They

frequently enter buildings by way of fireplace chimneys,

so seal off fireplaces when not in use.

When cleaning areas

previously used by mice, take precautions to reduce

exposure to dust, their excreta, and carcasses of dead

mice. Where deer mice or related species may be

reservoirs of hantaviruses, the area should be

disinfected by spraying it thoroughly with a

disinfectant or a solution of diluted household bleach

prior to beginning any sweeping, vacuuming, or handling

of surfaces or materials with which mice have had

contact. Use appropriate protective clothing, including

vinyl or latex gloves. Contact the Centers for Disease

Control (CDC) Hotline for current recommendations when

handling rodents or cleaning areas previously infested.

Frightening

There are no methods known for successfully keeping

white-footed or deer mice out of structures by means of

sound. Ultrasonic devices that are commercially sold and

advertised to control rodents and other pests have not

proven to give satisfactory control.

Repellents

Moth balls or flakes (naphthalene) may effectively

repel mice from closed areas where a sufficient

concentration of the chemical can be attained in the

air. These materials are not registered for the purpose

of repelling mice, however.

Toxicants

Anticoagulants. Anticoagulant baits such as warfarin,

diphacinone, chlorophacinone, brodifacoum, and

bromadiolone are all quite effective on white-footed and

deer mice, although they are not specifically registered

for use on these species. Brodifacoum and bromadiolone,

unlike the other anticoagulants, may be effective in a

single feeding. If baiting in and around structures is

done for house mice in accordance with label directions,

white-footed and deer mice usually will be controlled.

No violation of pesticide laws should be involved since

the “site” of bait application is the same.

Behavioral differences may

result in white-footed and deer mice carrying off and

hoarding more bait than house mice normally do. For this

reason, loose-grain bait formulations or secured

paraffin wax bait blocks may be more effective, since

these cannot be easily carried off. Cabins should be

baited before being left unoccupied. For further

information on anticoagulant baits and their use, see

the chapter House Mice.

Zinc phosphide. Various

zinc phosphide grain baits (1.0% to 2.0% active

ingredient) are registered for the control of Peromyscus

as well as voles and for post-harvest application in

orchards and at other sites. Zinc phosphide is a

single-dose toxicant, and all formulations are

Restricted Use Pesticides. Follow label directions when

applying. There are few damage situations where control

of white-footed or deer mice require the use of zinc

phosphide.

Fumigants

None are registered for white-footed or deer mice.

Because of the species’ habitat, there are few

situations where fumigation would be practical or

necessary.

Trapping

Ordinary mouse snap traps, sold in most grocery and

hardware stores, are effective in catching white-footed

and deer mice. Bait traps with peanut butter, sunflower

seed, or moistened rolled oats. For best results, use

several traps even if only a single mouse is believed to

be present. Set traps as you would for house mice:

against walls, along likely travel routes, and behind

objects. Automatic traps designed to live-capture

several house mice in a single setting also are

effective against white-footed and deer mice. They

should be checked frequently to dispose of captured mice

in an appropriate manner: euthanize them with carbon

dioxide gas in a closed container, or release them alive

into an appropriate location where they won’t cause

future problems. For further details on trapping, see

House Mice.

Other Methods

Recent research has revealed the possibility that

supplemental feeding at time of seeding can increase

survival of conifer seed by reducing predation by deer

mice, although the tests were not carried out to

germination.

Sunflower seed, and a

combination of sunflower and oats, were applied along

with Douglas fir and lodgepole pine seed in ratios

ranging from two to seven alternate foods to one conifer

seed. Significantly more conifer seeds survived mouse

predation for the 6and 9-week test periods than without

the supplemental feeding. For further details on the

experimental use of this technique, see Sullivan and

Sullivan (1982a and 1982b).

Economics of Damage and Control

Damage by both

white-footed and deer mice is usually a nuisance. When

mice destroy furniture or stored materials, the cost of

such damage depends upon the particular circumstances.

The greatest economic impact of deer mice is their

destruction of conifer seed in forest reseeding

operations. In west coast forest areas, Peromyscus seed

predation has resulted in millions of dollars worth of

damage and has been documented to have been a serious

problem since the early 1900s. New efficacious,

cost-effective methods of reducing this seed predation

are needed.

Acknowledgments

Much of the information in

this chapter was taken from Marsh and Howard (1990) and

from Schwartz and Schwartz (1981).

Figures 1 through 3 from

Schwartz and Schwartz (1981).

For

Additional Information

Burt, W. H., and R. P.

Grossenheider. 1976. A field guide to the mammals, 3d

ed. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. 289 pp.

Clark, J. P. 1986.

Vertebrate pest control handbook. California Dep. Food

Agric. Sacramento. 610 pp.

Everett, R. L., and R.

Stevens. 1981. Deer mouse consumption of bitterbrush

seed treated with four repellents. J. Range Manage.

34:393-396.

Howard, W. E., R. E.

Marsh, and R. E. Cole. 1968. Food detection by deer mice

using olfactory rather than visual cues. An. Behav.

16:13-17.

Howard, W. E., R. E.

Marsh, and R. E. Cole. 1970. A diphacinone bait for deer

mouse control. J. For. 68:220-222.

King, J. A., ed. 1968.

Biology of Peromyscus (Rodentia). Am. Soc. Mammal.,

Spec. Publ. 2. 539 pp.

Kirkland, G. L., Jr., and

J. N. Layne, eds. 1989. Advances in the study of

Peromyscus (Rodentia). Texas Tech. Univ. Press, Lubbock.

366 pp.

Marsh, R. E., and W. E.

Howard. 1990. Vertebrate pests. Pages 771-831 in A.

Mallis, ed. Handbook of pest control, 7th ed. Franzak

and Foster Co., Cleveland, Ohio.

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri, rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp.

Sullivan, T. P., and D. S.

Sullivan. 1982a. The use of alternative foods to reduce

lodgepole pine seed predation by small mammals. J. Appl.

Ecol. 19:33-45.

Sullivan, T. P., and D. S.

Sullivan. 1982b. Reducing conifer seed predation by use

of alternative foods. J. For. 80:499-500.

Taitt, M. J. 1981. The

effect of extra food on small rodent populations: I.

Deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus). J. An. Ecol.

50:111-124.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom; Robert

M. Timm; Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|