|

|

|

|

|

RODENTS: Gophers, Pocket |

|

|

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

- Exclusion

- Generally not

practical. Small mesh wire fence may provide

protection for ornamental trees and shrubs or flower

beds. Plastic netting protects seedlings.

- Cultural Methods

- Damage resistant

varieties of alfalfa. Crop rotation. Grain buffer

strips. Control of tap-rooted forbs. Flood

irrigation. Plant naturally resistant varieties of

seedlings.

- Repellents

- Synthetic predator

odors are all of questionable benefit.

- Toxicants

- Baits: Strychnine

alkaloid. Zinc phosphide. Chlorophacinone.

Diphacinone.

- Fumigants:

- Carbon monoxide

from engine exhaust. Others are not considered very

- effective, but

some are used: Aluminum phosphide. Gas cartridges.

- Trapping

- Various

specialized gopher kill traps. Common spring or pan

trap (sizes No. 0 and No. 1).

- Shooting

- Not practical.

- Other

- Buried irrigation

pipe or electrical cables can be protected with

cylindrical pipe having an outside diameter of at

least 2.9 inches (7.4 cm).

- Surrounding a

buried cable with 6 to 8 inches (15 to 20 cm) of

coarse gravel (1 inch [2.5 cm] in diameter) may

provide some protection.

Identification

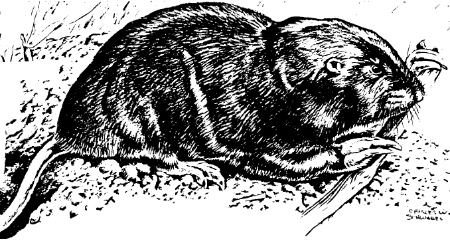

Pocket gophers (Fig. 1)

are fossorial (burrowing) rodents, so named because they

have fur-lined pouches outside of the mouth, one on each

side of the face (Fig. 2). These pockets, which are

capable of being turned inside out, are used for

carrying food. Pocket gophers are powerfully built in

the forequarters and have a short neck; the head is

fairly small and flattened. The forepaws are

large-clawed and the lips close behind their large

incisors, all marvelous adaptations to their underground

existence.

Gophers have small

external ears and small eyes. As sight and sound are

severely limited, gophers are highly dependent on the

sense of touch. The vibrissae (whiskers) on their face

are very sensitive to touch and assist pocket gophers

while traveling about in their dark tunnels. The tail is

sparsely haired and also serves as a sensory mechanism

guiding gophers’ backward movements. The tail is also

important in thermoregulation, acting as a radiator.

Pocket gophers are

medium-sized rodents ranging from about 5 to nearly 14

inches (13 to 36 cm) long (head and body). Adult males

are larger than adult females. Their fur is very fine,

soft, and highly variable in color. Colors range from

nearly black to pale brown to almost white. The great

variability in size and color of pocket gophers is

attributed to their low dispersal rate and thus limited

gene flow, resulting in adaptation to local conditions.

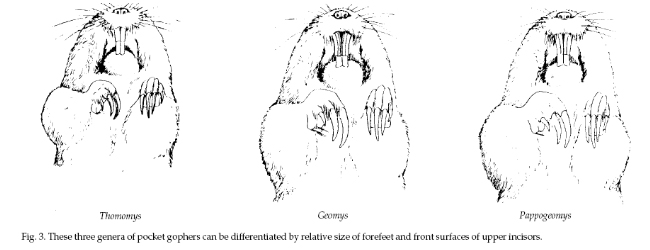

Thirty-four species of

pocket gophers, represented by five genera, occupy the

western hemisphere. In the United States there are 13

species and three genera. The major features

differentiating these genera are the size of their

forefeet, claws, and front surfaces of their chisel-like

incisors (Fig. 3).

small forefeet with small

claws. Northern pocket gophers (Thomomys talpoides) are

typically from 6 1/2 to 10 inches (17 to 25 cm) long.

Their fur is variable in color but is often yellowish

brown with pale underparts. Botta’s (or valley) pocket

gophers (Thomomys bottae) are extremely variable in size

and color. Botta’s pocket gophers are 5 inches to about

13 1/2 inches (13 to 34 cm) long. Their color varies

from almost white to black.

Geomys

have two grooves on each upper incisor and large

forefeet and claws. Plains pocket gophers (Geomys

bursarius) vary in length from almost 7 1/2 to 14 inches

(18 to 36 cm). Their fur is typically brown but may vary

to black. Desert pocket gophers (Geomys arenarius) are

always brown and vary from nearly 8 3/4 to 11 inches (22

to 28 cm) long. Texas pocket gophers (Geomys personatus)

are also brown and are from slightly larger than 8 3/4

to nearly 13 inches (22 to 34 cm) long. Southeastern

pocket gophers (Geomys pinetis) are of various shades of

brown, depending on soil color, and are from 9 to 13 1/4

inches (23 to 34 cm) long.

Pappogeomys

have a single groove on each upper incisor and, like

Geomys, have large forefeet with large claws.

Yellow-faced pocket gophers (Pappogeomys castanops) vary

in length from slightly more than 5 1/2 to just less

than 7 1/2 inches (14 to 19 cm). Their fur color varies

from pale yellow to dark reddish brown. The underparts

vary from whitish to bright yellowish buff. Some hairs

on the back and top of the head are dark-tipped.

Range Range

Pocket gophers are found

only in the Western Hemisphere. They range from Panama

in the south to Alberta in the north. With the exception

of the southeastern pocket gopher, they occur throughout

the western two-thirds of the United States.

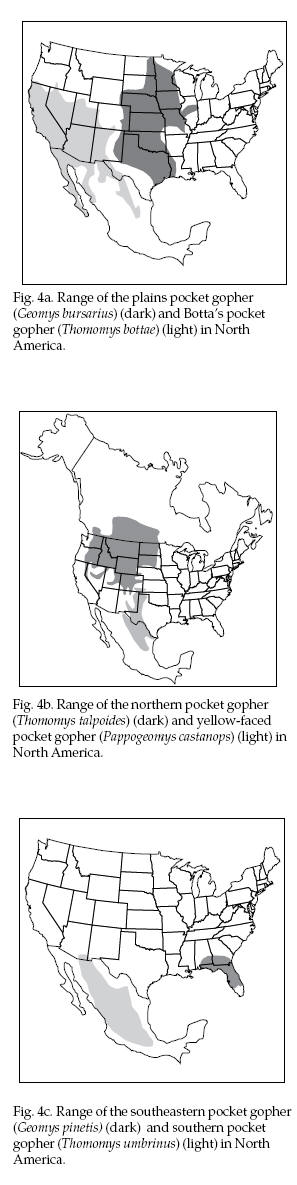

Plains pocket gophers (Geomys

bursarius, Fig. 4a) are found in the central plains from

Canada south through Texas and Louisiana. Botta’s (or

valley) pocket gophers (Thomomys bottae, Fig. 4a) are

found in most of the southern half of the western United

States.

Northern pocket gophers

(Thomomys talpoides, Fig. 4b) range throughout most of

the states in the northern half of the western United

States. Yellow-faced pocket gophers (Pappogeomys

castanops, Fig. 4b) occur from Mexico, along the western

edge of Texas, eastern New Mexico, southeastern

Colorado, southwestern Kansas, and into the panhandle of

Oklahoma.

Southeastern pocket

gophers (Geomys pinetis, Fig. 4c) are found in northern

and central Florida, southern Georgia, and southeastern

Alabama. Southern pocket gophers (Thomomys umbrinus,

Fig. 4c) range primarily in Central America, but occur

in extreme southwestern New Mexico and southeastern

Arizona. Desert pocket gophers (Geomys arenarius) occur

only in southwestern New Mexico and the extreme western

edge of Texas. Mazama pocket gophers (Thomomys mazama,),

mountain pocket gophers (Thomomys monticola ), and Camas

pocket gophers (Thomomys bulbivorus) have more limited

distributions in the extreme western United States.

Habitat

A wide variety of

habitats are occupied by pocket gophers. They occur from

low coastal areas to elevations in excess of 12,000 feet

(3,600 m). Pocket gophers similarly are found in a wide

variety of soil types and conditions. They reach their

greatest densities on friable, light-textured soils with

good herbage production, especially when that vegetation

has large, fleshy roots, bulbs, tubers, or other

underground storage structures.

The importance of soil

depth and texture to the presence or absence of gophers

is both obvious and cryptic. Shallow soils may be

subject to cave-ins and thus will not maintain a tunnel.

Tunnels are deeper in very sandy soils where soil

moisture is sufficient to maintain the integrity of the

burrow. A less visible requirement is that atmospheric

and exhaled gases must diffuse through the soil to and

from the gopher’s tunnel. Thus light-textured, porous

soils with good drainage allow for good gas exchange

between the tunnel and the atmosphere. Soils that have a

very high clay content or those that are continuously

wet diffuse gases poorly and are unsuitable for gophers.

Pocket gophers

sometimes occupy fairly rocky habitats, although those

habitats generally do not have more than 10% rocks in

the top 8 inches (20 cm) of soil. Pocket gophers appear

to burrow around rocks greater than 1 inch (2.5 cm) in

diameter, but smaller rocks are frequently pushed to the

surface.

Soil depth is also

important in ameliorating temperatures. Soils less than

4 inches (10 cm) deep probably are too warm during

summers. Shallow tunnels may also limit the presence of

gophers during cold temperatures, especially if an

insulating layer of snow is absent.

Typically, only one

species of pocket gopher is found in each locality. Soil

factors are important in limiting the distributions of

pocket gophers. The larger gophers are restricted to

sandy and silty soils east of the Rockies. Smaller

gophers of the genus Thomomys have a broader tolerance

to various soils.

Food

Habits

Pocket gophers feed on

plants in three ways: 1) they feed on roots that they

encounter when digging; 2) they may go to the surface,

venturing only a body length or so from their tunnel

opening to feed on aboveground vegetation; and 3) they

pull vegetation into their tunnel from below. Pocket

gophers eat forbs, grasses, shrubs, and trees. They are

strict herbivores, and any animal material in their diet

appears to result from incidental ingestion.

Alfalfa and dandelions are

apparently some of the most preferred and nutritious

foods for pocket gophers. Generally, Thomomys prefer

perennial forbs, but they will also eat annual plants

with fleshy underground storage structures. Plains

pocket gophers consume primarily grasses, especially

those with rhizomes, but they seem to prefer forbs when

they are succulent in spring and summer.

Portions of plants

consumed also vary seasonally. Gophers utilize

above-ground portions of vegetation mostly during the

growing season, when the vegetation is green and

succulent. Height and density of vegetation at this time

of year may also offer protection from predators,

reducing the risk of short surface trips. Year-round,

however, roots are the major food source. Many trees and

shrubs are clipped just above ground level. This occurs

principally during winter under snow cover. Damage may

reach as high as 10 feet (3 m) above ground. Seedlings

also have their roots clipped by pocket gophers.

Several mammals are

sometimes confused with pocket gophers because of

variations in common local terminology (Fig. 5). In

addition, in the southeastern United States, pocket

gophers are called “salamanders,” (derived from the term

sandy mounder), while the term gopher refers to a

tortoise. Pocket gophers can be distinguished from the

other mammals by their telltale signs as well as by

their appearance. Pocket gophers leave soil mounds on

the surface of the ground. The mounds are usually

fan-shaped and tunnel entrances are plugged, keeping

various intruders out of burrows.

Damage caused by gophers

includes destruction of underground utility cables and

irrigation pipe, direct consumption and smothering of

forage by earthen mounds, and change in species

composition on rangelands by providing seedbeds (mounds)

for invading annual plants. Gophers damage trees by stem

girdling and clipping, root pruning, and possibly root

exposure caused by burrowing. Gopher mounds dull and

plug sicklebars when harvesting hay or alfalfa, and soil

brought to the surface as mounds is more likely to

erode. In irrigated areas, gopher tunnels can channel

water runoff, causing loss of surface irrigation water.

Gopher tunnels in ditch banks and earthen dams can

weaken these structures, causing water loss by seepage

and piping through a bank or the complete loss or

washout of a canal bank. The presence of gophers also

increases the likelihood of badger activity, which can

also cause considerable damage.

Legal Status

Pocket gophers are not

protected by federal or state law.

Exclusion

Because of the expense and

limited practicality, exclusion is of little use.

Fencing of highly valued ornamental shrubs or landscape

trees may be justified. The fence should be buried at

least 18 inches (46 cm). The mesh should be small enough

to exclude gophers: 1/4-inch or 1/2-inch (6- to 13-mm)

hardware cloth will suffice. Cylindrical plastic netting

placed over the entire seedling, including the bare

root, reduces damage to newly planted forest seedlings

significantly.

Cultural Methods and

Habitat Modification

These methods take

advantage of knowledge of the habitat requirements of

pocket gophers or their feeding behavior to reduce or

eliminate damage.

Crop Varieties. In

alfalfa, large tap-rooted plants may be killed or the

vigor of the plant greatly reduced by pocket gophers

feeding on the roots. Varieties with several large roots

rather than a single taproot suffer less when gophers

feed on them. Additionally, pocket gophers in alfalfa

fields with fibrous-root systems may have smaller

ranges. This would reduce gopher impact on yield.

Crop Rotation. There are

many good reasons for using a crop rotation scheme, not

the least of which is minimizing problems with pocket

gophers. When alfalfa is rotated with grain crops, the

resultant habitat is incapable of supporting pocket

gophers. The annual grains do not establish large

underground storage structures and thus there is

insufficient food for pocket gophers to survive

year-round.

Grain Buffer Strips.

Planting 50foot (15-m) buffer strips of grain around hay

fields provides unsuitable habitat around the fields and

can minimize immigration of gophers.

Weed Control. Chemical or

mechanical control of forbs, which frequently have large

underground storage structures, can be an effective

method of minimizing damage by Thomomys to rangelands.

It may also be effective in making orchards and

shelterbelts less suitable for pocket gophers. The

method is less effective for plains pocket gophers as

they survive quite nicely on grasses. The warm-season

prairie grasses have large root-to-stem ratios and these

food sources are adequate for Geomys.

Flood Irrigation.

Irrigating fields by flooding can greatly reduce habitat

suitability for pocket gophers. Water can fill a

gopher’s tunnel, thus causing the occupant to drown or

flee to the surface, making it vulnerable to predation.

The soil may be so damp that it becomes sticky. This

will foul the pocket gopher’s fur and claws. As the soil

becomes saturated with water, the diffusion of gases

into and out of the gopher’s burrow is inhibited,

creating an inhospitable environment. The effectiveness

of this method can be enhanced by removing high spots in

fields that may serve as refuges during irrigation.

Damage-Resistant Plant

Varieties. Tests of several provenances of ponderosa

pine showed that some have natural resistance to gopher

damage.

Repellents

Some predator odors have

been tested as gopher repellents and show some promise.

Commercially available sonic devises are claimed to

repel pocket gophers. There is, however, no scientific

supporting evidence. The plants known as caper spurge,

gopher purge, or mole plant (Euphorbia lathyrus) and the

castor-oil plant (Ricinus communis) have been promoted

as gopher repellents, but there is no evidence of their

effectiveness. In addition, these are not recommended as

they are both poisonous to humans and pets.

Toxicants

Several rodenticides

currently are federally registered and available for

pocket gopher control. The most widely used and

evaluated is strychnine alkaloid (0.25 to 0.5% active

ingredient) on grain baits. There is some concern that

pocket gophers may consume sublethal doses of strychnine

and then develop bait shyness. Strychnine acts very

rapidly and gophers sometimes die within an hour after

consuming a lethal dose. It is registered for use for

Geomys spp. and Thomomys spp. If the label has

directions for use with a burrow builder machine, then

it is a Restricted Use Pesticide. Zinc phosphide (2%) is

less effective than strychnine for gopher control.

Anticoagulants now are available for pocket gopher

control. Currently, the only federally registered

products are chlorophacinone and diphacinone.

To poison pocket gophers, the bait must be placed in

their tunnel systems by hand or by a special machine

known as a burrow builder. Underground baiting for

pocket gopher control with strychnine presents minimal

hazards to nontarget wildlife, either by direct

consumption of bait or by eating poisoned gophers.

Poison bait spilled on the surface of the ground may be

hazardous to ground-feeding birds such as mourning

doves.

The main drawback to grain

baits is their high susceptibility to decomposition in

the damp burrows. A new product that contains a grain

mixture plus the anticoagulant, diphacinone, in a

paraffin block not only increases the bait’s effective

life, but also makes it possible for more than one

gopher to be killed with the same bait. Once the

resident gopher ingests the toxicant and dies, it is

typical for a neighboring gopher to take over the tunnel

system and thus to ingest the still-toxic bait.

Hand Baiting. Bait can be

placed in a burrow system by hand, using a special

hand-operated bait dispenser probe, or by making an

opening to the burrow system with a probe. Placing bait

in the burrow by hand is more time-consuming than either

of the probing methods, but there is no doubt that the

bait is delivered to the tunnel system.

The key to efficient and

effective use of these methods is locating the burrow

system. The main burrow generally is found 12 to 18

inches (30 to 46 cm) away from the plug on the

fan-shaped mounds (Fig. 6). If you use a trowel or

shovel to locate the main burrow, dig 12 to 18 inches

(30 to 46 cm) away from the plug. When the main burrow

is located, place a rounded tablespoon (15 ml) of bait

in each direction. Place the bait well into each tunnel

system with a long-handled spoon and then block off each

tunnel with sod clumps and soil. Bait blocks are also

applied in this manner. The reason for closing the

burrow is that pocket gophers are attracted to openings

in their system with the intent of closing them with

soil. Thus, if there is a detectable opening near the

placement of poison, the pocket gopher may cover the

bait with soil as it plugs the opening. Pocket gophers

normally travel all portions of their burrow system

during a day.

Place a probe for pocket

gopher tunnels where you expect to locate the main

burrow as described above (plans for making a probe and

instructions for use are presented in figure 7). You

will know you have located a burrow by the decreased

friction on the probe. With a reservoir-type bait probe

dispenser (Fig. 8), a button is pushed when the probe is

in a burrow and a metered dose of bait drops into the

burrow. With the burrow probe (without a bait

reservoir), make an opening from the surface of the

ground to the burrow. Place about a tablespoon (15 ml)

of bait down the probe opening. This method is much

quicker than digging open the burrow tunnel. For best

control, dose each burrow system in two or three places.

Be sure to cover the probe hole with a sod clump so that

the pocket gopher does not cover the bait when attracted

to the opening in its burrow. Greater doses of

chlorophacinone or other locally registered

anticoagulants are recommended (1/2 cup [120 ml]) at

each of two or three locations in each burrow. Also,

since some gophers poisoned in this manner die

aboveground, the area should be checked periodically for

10 to 14 days after treatment. Any dead gophers found

should be buried or incinerated.

Mechanical Burrow Builder.

The burrow builder (Fig. 9) delivers bait underground

mechanically, so large areas can be economically treated

for pocket gopher control. It is tractor-drawn and is

available in hydraulically operated units or three-point

hitch models.

The device consists of a

knife and torpedo assembly that makes the artificial

burrow at desired soil depths, a coulter blade that cuts

roots of plants ahead of the knife, a seeder assembly

for bait dispensing, and the packer wheel assembly to

close the burrow behind the knife. The seeder box has a

metering device for dispensing various toxic baits at

desired rates.

The artificial burrows

should be constructed at a depth similar to those

constructed by gophers in your area. The artificial

burrows may intercept the gopher burrows, or the gophers

may inquisitively enter the artificial burrows, gather

bait in their cheek pouches, and return to their burrow

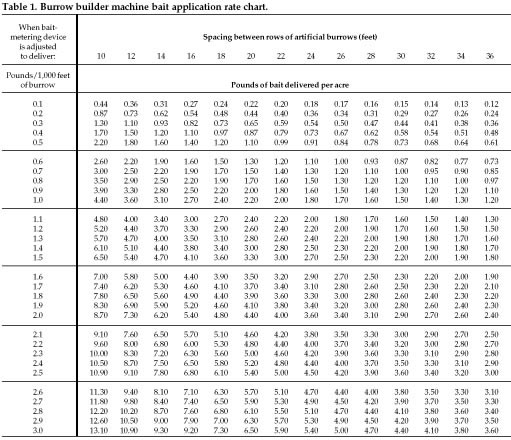

system to consume the bait. Recommended application

rates of 1 to 2 pounds per acre (1.1 to 2.2 kg/ha) of

0.3 to 0.5% strychnine alkaloid grain should provide an

85% to 95% reduction in the gopher population (Table 1

demonstrates how to calculate bait delivery rates). The

burrows should be spaced at 20- to 25-foot (6- to 8-m)

intervals. To assure success:

Operate the burrow builder

parallel to the ground surface, at a depth where gophers

are active. It is essential to check the artificial

burrow. If the soil is too dry, a good burrow will not

be formed; if the soil is too wet and sticky, soil will

accumulate on packer wheels or even on the knife shank

and the slot may not close adequately.

Check periodically to note

whether bait is being dispensed. Sometimes the tube gets

clogged with soil.

Encircle the perimeter of

the field with artificial burrows to deter reinvasions.

Follow directions provided

with the burrow builder machine. It is especially

important to scour the torpedo assembly by pulling it

through sandy soils so that smooth burrows will be

constructed.

It is especially important

to scour the torpedo assembly by pulling it through

sandy soils so that smooth burrows will be constructed.

EXAMPLE: To determine the

amount of bait that will be delivered if a mechanical

baiter is set to apply 0.5 pound per 1,000 feet of

burrow, and is to be used between orchard rows with

22-foot spacings, read down row spacing column 22 until

opposite the designated 0.5 pound. The answer (to the

nearest hundredth) is 0.99 pound.

Fumigants

Federally registered

fumigants include aluminum phosphide and gas cartridges

with various active ingredients. These fumigants usually

are not very successful in treating pocket gophers

because the gas moves too slowly through the tunnel

system. Unless the soil is moist, the fumigant will

diffuse through the soil out of the gopher’s tunnel.

Carbon monoxide from

automobile exhaust is more effective than other

fumigants because of its greater volume and pressure.

Connect a piece of hose or pipe to the engine exhaust,

and place it in a tunnel near a fresh soil mound. Pack

soil around the hose or pipe and allow the engine to run

for about 3 minutes. The method is usually 90%

effective. The engines of newer vehicles with

antipollution devices require a longer running time

since they do not produce as much carbon monoxide. This

procedure requires no registration.

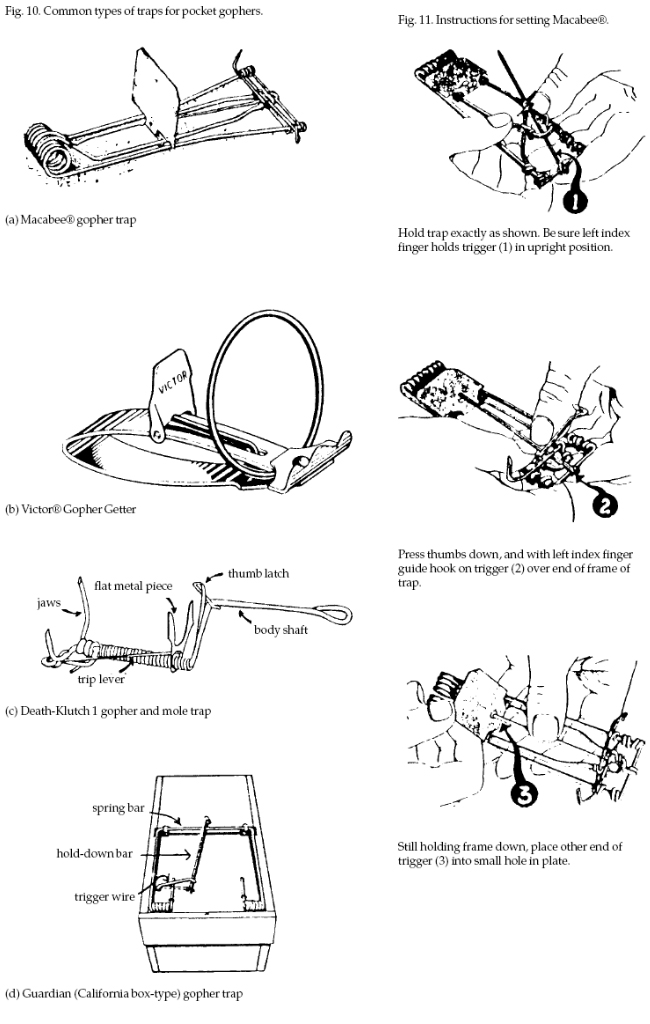

Trapping

Trapping is extremely

effective for pocket gopher control in small areas and

for removal of remaining animals after a poisoning

control program. Some representative traps are

illustrated on the following page (Fig. 10) with

instructions for setting them (Figs. 11 and 12).

Vulnerability to trapping

differs among species of pocket gophers and sometimes

within the same species in different areas and at

different times of the year.

For effective trapping,

the first requisite is to find the tunnel. The procedure

will vary depending on whether traps are set in the main

tunnel or in the lateral tunnels (Fig. 13). To locate

traps in the main tunnel, refer to the section on hand

baiting. To locate the lateral tunnels, find a fresh

mound and with a trowel or shovel, dig several inches

away from the mound on the plug side. The lateral may be

plugged with soil for several inches (cm) or several

feet (m). However, fresh mounds are usually plugged only

a few inches.

You may have to experiment

with trap type and placement. Some trappers have success

leaving tunnels completely open when they set their

traps; others, when they place traps in the main, close

off the tunnel completely, and when trapping the

lateral, close most of the tunnel with sod. Traps can be

marked above ground with engineering flags and should be

anchored with a stake and wire or chain so a predator

does not carry off the catch and the trap.

Trapping can be done

year-round because gophers are always active, but a

formidable effort is required for trapping when the soil

is frozen. Trapping is most effective when gophers are

pushing up new mounds, generally in spring and fall. If

a trap is not visited within 48 hours, move it to a new

location. Leave traps set in a tunnel system even if you

have trapped a gopher in spring and early summer, when

gophers are most likely to share their quarters.

Shooting

Since pocket gophers spend

essentially all their time below ground, this method is

impractical.

Other

Methods

Buried utility cables and

irrigation lines can be protected by enclosing them in

various materials, as long as the outside diameter

exceeds 2.9 inches (7.4 cm). Gophers can open their

mouths only wide enough to allow about a 1-inch (2.5-cm)

span between the upper and lower incisors. Thus, the

recommended diameter presents an essentially flat

surface to most pocket gophers. Cables can be protected

in this manner whether they are armored or not. Soft

metals such as lead and aluminum used for armoring

cables are readily damaged by pocket gophers if the

diameters are less than the suggested sizes.

Buried cables may be

protected from gopher damage by surrounding the cable

with 6 to 8 inches (15 to 20 cm) of coarse gravel.

Pocket gophers usually burrow around gravel 1 inch (2.5

cm) in diameter, whereas smaller pebbles may be pushed

to the surface.

Economics of Damage and Control

It is relatively easy to

determine the value of the forage lost to pocket

gophers. Botta’s pocket gophers at a density of 32 per

acre (79/ha) decreased the forage yield by 25% on

foothill rangelands in California, where the plants were

nearly all annuals. Plains pocket gophers reduced forage

yield on rangelands in western Nebraska by 21% to 49% on

different range sites. Alfalfa yields in eastern

Nebraska were reduced as much as 46% in dryland and 35%

in irrigated alfalfa. Losses of 30% have been reported

for hay meadows.

Calculating the cost of

control operations is only slightly more complicated.

However, the benefit-cost analysis of control is still

not straightforward. More research data are needed on

managing the recovery of forage productivity. For

example, should range be fertilized, rested, or lightly

grazed? Should gopher mounds on alfalfa be lightly

harrowed? A study of northern pocket gopher control on

range production in southern Alberta indicated that

forage yields increased 16%, 3 months after treatment.

The potential for complete yield recovery the first year

following gopher removal has been noted for a

fibrous-rooted variety of alfalfa.

Economic assessment should

also be made to determine the cost of no control, the

speed of pocket gopher infestation, and the costs

associated with dulled or plugged mowing machinery or

mechanical breakdowns caused by the mounds. Assessment

could also be made for damages to buried cable,

irrigation structures, trees, and so on.

The benefits of pocket

gophers also complicate the economic analysis. Some of

these benefits are: (1) increased soil fertility by

adding organic matter such as buried vegetation and

fecal wastes; (2) increased soil aeration and decreased

soil compaction; (3) increased water infiltration and

thus decreased runoff; and (4) increased rate of soil

formation by bringing subsoil material to the surface of

the ground, subjecting it to weathering.

Decisions on whether or

not to control gophers may be influenced by the animals’

benefits, which are long-term and not always readily

recognized, and the damage they cause, which is obvious

and sometimes substantial in the short-term. Landowners

who are currently troubled by pocket gophers can gain

tremendously by studying the gophers’ basic biology.

They would gain economically by learning how to manage

their systems with pocket gophers in mind, and

aesthetically by understanding how this interesting

animal “makes a living.”

The distribution of

gophers makes it unlikely that control measures will

threaten them with extinction. Local eradication may be

desirable and cost-effective in some small areas with

high-value items. On the other hand, it may be effective

to simply reduce a population. There are also times when

control is not cost-effective and therefore inadvisable.

Complete control may upset the long-term integrity of

ecosystems in a manner that we cannot possibly predict

from our current knowledge of the structure and function

of those systems.

Acknowledgments

We thank the many

researchers and managers who have spent untold time

studying these extremely interesting rodents. Some are

listed in the reference section. Special thanks are due

to Scott Hygnstrom for his editorial assistance; to Rex

E. Marsh, Bob Timm, and Jan Hygnstrom for their helpful

comments on an earlier draft, and to Diane Gronewold and

Diana Smith for their technical assistance.

Figures 1, 2, and 6 from

Schwartz and Schwartz (1981).

Figures 3 and 5 from

Turner et al. (1973).

Figures 4a, 4b, and 4c

after Hegdal and Harbour (1991), adapted by BruceJasch

and Dave Thornhill.

Figures 7, 8, and 10 by

Jill Sack Johnson.

Figure 9 courtesy of

Elston Equipment Company.

Figure 11 courtesy of Z.

A. Macabee Gopher Trap Company.

Figure 12 courtesy of P-W

Manufacturing Company.

Figure 13 adapted from E.

K. Boggess (1980), “Pocket Gophers,” in Handbook on

Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage, Kansas State

University, Manhattan.

Table 1 taken from Marsh

and Cummings (1977).

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

11/14/2006

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|