|

|

|

|

|

RODENTS: Chipmunks |

|

|

Fig. 1. Eastern chipmunk,

Tamias striatus

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

-

Exclusion

-

Rodent-proof

construction will exclude chipmunks from structures.

-

Use 1/4-inch (0.6-cm)

mesh hardware cloth to exclude chipmunks from

gardens and flower beds.

-

Habitat Modification

-

Store food items, such

as bird seed and dog food, in rodent-proof

containers.

-

Ground covers, shrubs,

and wood piles should not be located adjacent to

structure foundations.

-

Frightening

-

Not effective.

-

Repellents

-

Area repellents.

Naphthalene (moth flakes or moth balls) may be

effective if liberally applied in confined places.

-

Taste repellents.

Repellents containing bitrex, thiram, or ammonium

soaps of higher fatty acids applied to flower bulbs,

seeds, and vegetation (not for human consumption)

may control feeding damage.

-

Toxicants

-

None are federally

registered. Check with local extension agents or a

USDA-APHIS-ADC personnel for possible Special Local

Needs 24(c) registrations.

-

Fumigants

-

Generally impractical.

-

Trapping

-

Rat-sized snap traps.

Live (box or cage) traps. Glue boards.

-

Shooting

-

Small gauge shotguns

or .22-caliber rifles.

Identification

Fifteen species of native

chipmunks of the genus Eutamias and one of the genus

Tamias are found in North America. The eastern chipmunk

(Tamias striatus) and the least chipmunk (Eutamias

minimas), discussed here, are the two most widely

distributed and notable species. Behavior and damage is

similar among all species of native chipmunks.

Therefore, damage control recommendations are similar

for all species.

The eastern chipmunk is a

small, brownish, ground-dwelling squirrel. It is

typically 5 to 6 inches (13 to 15 cm) long and weighs

about 3 ounces (90 g). It has two tan and five blackish

longitudinal stripes on its back, and two tan and two

brownish stripes on each side of its face. The

longitudinal stripes end at the reddish rump. The tail

is 3 to 4 inches (8 to 10 cm) long and hairy, but it is

not bushy (Fig. 1).

The least chipmunk is the

smallest of the chipmunks. It is typically 3 2/3 to 4

1/2 inches (9 to 11 cm) long and weighs 1 to 2 ounces

(35 to 70 g). The color varies from a faint yellowish

gray with tawny dark stripes (Badlands, South Dakota) to

a grayish tawny brown with black stripes (Wisconsin and

Michigan). The stripes, however, continue to the base of

the tail on all least chipmunks.

Chipmunks are often

confused with thirteen-lined ground squirrels (Spermophilus

tridecemlineatus), also called “striped gophers,” and

red squirrels (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus). The

thirteen-lined ground squirrel is yellowish, lacks the

facial stripes, and its tail is not as hairy as the

chipmunk’s. As this squirrel’s name implies, it has 13

stripes extending from the shoulder to the tail on each

side and on its back. When startled, a ground squirrel

carries its tail horizontally along the ground; the

chipmunk carries its tail upright. The thirteen-lined

ground squirrel’s call sounds like a high-pitched

squeak, whereas chipmunks have a rather sharp

“chuck-chuck-chuck” call. The red squirrel is very vocal

and has a high-pitched chatter. It is larger than the

chipmunk, has a bushier tail and lacks the longitudinal

stripes of the chipmunk. Red squirrels spend a great

deal of time in trees, while chipmunks spend most of

their time on the ground, although they can climb trees.

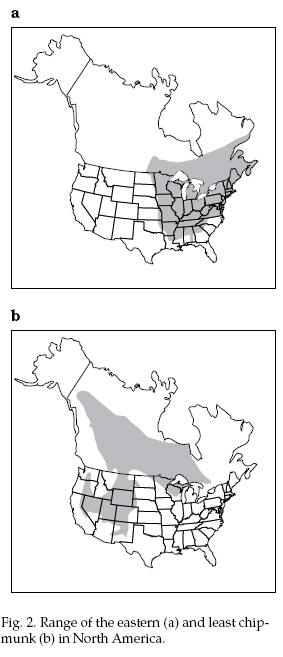

Range Range

The eastern chipmunk’s

range includes most of the eastern United States. The

least chipmunk’s range includes most of Canada, the US

Rocky Mountains, the Great Basin, and parts of the upper

Midwest (Fig. 2).

Habitat

and General Biology

Eastern chipmunks

typically inhabit mature woodlands and woodlot edges,

but they also inhabit areas in and around suburban and

rural homes. Chipmunks are generally solitary except

during courtship or when rearing young.

The least chipmunk

inhabits low sagebrush deserts, high mountain coniferous

forests, and northern mixed hardwood forests.

The home range of a

chipmunk may be up to 1/2 acre (0.2 ha), but the adult

only defends a territory about 50 feet (15.2 m) around

the burrow entrance. Chipmunks are most active during

the early morning and late afternoon. Chipmunk burrows

often are well-hidden near objects or buildings (for

example, stumps, wood piles or brush piles, basements,

and garages). The burrow entrance is usually about 2

inches (5 cm) in diameter. There are no obvious mounds

of dirt around the entrance because the chipmunk carries

the dirt in its cheek pouches and scatters it away from

the burrow, making the burrow entrance less conspicuous.

In most cases, the

chipmunk’s main tunnel is 20 to 30 feet (6 m to 9 m) in

length, but complex burrow systems occur where cover is

sparse. Burrow systems normally include a nesting

chamber, one or two food storage chambers, various side

pockets connected to the main tunnel, and separate

escape tunnels.

With the onset of cold

weather, chipmunks enter a restless hibernation and are

relatively inactive from late fall through the winter

months. Chipmunks do not enter a deep hibernation as do

ground squirrels, but rely on the cache of food they

have brought to their burrow. Some individuals become

active on warm, sunny days during the winter. Most

chipmunks emerge from hibernation in early March.

Eastern chipmunks mate two

times a year, during early spring and again during the

summer or early fall. There is a 31-day gestation

period. Two to 5 young are born in April to May and

again in August to October. The young are sexually

mature within 1 year. Adults may live up to 3 years.

Adult least chipmunks mate

over a period of 4 to 6 weeks from April to mid-July.

Least chipmunks produce 1 litter of 2 to 7 young in May

or June. Occasionally a second litter is produced in the

fall.

Chipmunk pups appear above

ground when they are 4 to 6 weeks old — 2/3 the size of

an adult. Young will leave the burrow at 6 to 8 weeks.

Population densities of

chipmunks are typically 2 to 4 animals per acre (5 to

10/ha). Eastern chipmunk population densities may be as

high as 10 animals per acre (24/ha), however, if

sufficient food and cover are available. Home ranges

often overlap among individuals.

Food Habits

The diet of chipmunks

consists primarily of grains, nuts, berries, seeds,

mushrooms, insects, and carrion. Although chipmunks are

mostly ground-dwelling rodents, they regularly climb

trees in the fall to gather nuts, fruits, and seeds.

Chipmunks cache food in their burrows throughout the

year. By storing and scattering seeds, they promote the

growth of various plants.

Chipmunks also prey on

young birds and bird eggs. Chipmunks themselves serve as

prey for several predators.

Damage and Damage Identification

Throughout their North

American range, chipmunks are considered minor

agricultural pests. Most conflicts with chipmunks are

nuisance problems. When chipmunks are present in large

numbers they can cause structural damage by burrowing

under patios, stairs, retention walls, or foundations.

They may also consume flower bulbs, seeds, or seedlings,

as well as bird seed, grass seed, and pet food that is

not stored in rodent-proof storage containers. In New

England, chipmunks and tree squirrels cause considerable

damage to maple sugar tubing systems by gnawing the

tubes.

Legal Status

Chipmunks are not

protected by federal law, but state and local

regulations may apply. Most states allow landowners or

tenants to take chipmunks when they are causing or about

to cause damage. Some states, (for example, Georgia,

North Carolina, and Arkansas) require a permit to kill

nongame animals. Other states are currently developing

laws to protect all nongame species. Consult your local

conservation agency or USDA-APHIS-ADC personnel for the

legal status of chipmunks in your state.

Damage Prevention and Control

Exclusion

Chipmunks should be excluded from buildings wherever

possible. Use hardware cloth with 1/4-inch (0.6-cm)

mesh, caulking, or other appropriate materials to close

openings where they could gain entry.

Hardware cloth may also be

used to exclude chipmunks from flower beds. Seeds and

bulbs can be covered by 1/4-inch (0.6-cm) hardware cloth

and the cloth itself should be covered with soil. The

cloth should extend at least 1 foot (30 cm) past each

margin of the planting. Exclusion is less expensive in

the long run than trapping, where high populations of

chipmunks exist.

Cultural Methods and

Habitat Modifications

Landscaping features, such as ground cover, trees,

and shrubs, should not be planted in continuous fashion

connecting wooded areas with the foundations of homes.

They provide protection for chipmunks that may attempt

to gain access into the home. It is also difficult to

detect chipmunk burrows that are adjacent to foundations

when wood piles, debris, or plantings of ground cover

provide above-ground protection.

Place bird feeders at

least 15 to 30 feet (5 to 10 m) away from buildings so

spilled bird seed does not attract and support chipmunks

near them.

Repellents

Naphthalene flakes (“moth flakes”) may repel

chipmunks from attics, summer cabins, and storage areas

when applied liberally (4 to 5 pounds of naphthalene

flakes per 2,000 square feet [1.0 to 1.2 kg/100 m2]).

Use caution, however, in occupied buildings, as the odor

may also be objectionable or irritating to people or

pets.

There are currently no

federally registered repellents for controlling rodent

damage to seeds, although some states have Special Local

Needs 24(c) registrations for this purpose. Taste

repellents containing bitrex, thiram, or ammonium soaps

of higher fatty acids can be used to protect flower

bulbs, seeds, and foliage not intended for human

consumption. Multiple applications of repellents are

required. Repellents can be expensive and usually do not

provide 100% reduction in damage to horticultural

plantings.

Toxicants

There are no toxic baits registered for controlling

chipmunks. Baits that are used against rats and mice in

and around homes will also kill chipmunks although they

are not labeled for such use and cannot be recommended.

Moreover, chipmunks that die from consuming a toxic bait

inside structures may create an odor problem for several

days. Some states have Special Local Needs 24(c)

registrations for chipmunk control for site-specific

use.

Consult a professional

pest control operator or USDA-APHIS-ADC biologist if

chipmunks are numerous or persistent.

Fumigants

Fumigants are generally ineffective because of the

difficulty in locating the openings to chipmunk burrows

and because of the complexity of burrows.

Aluminum phosphide is a

Restricted Use Pesticide that is registered in many

states for the control of burrowing rodents. It is

available in a tablet form, which when dropped into the

burrow reacts with the moisture in the soil and

generates toxic phosphine gas.

Aluminum phosphide,

however, cannot be used in, under, or even near occupied

buildings because there is a danger of the fumigant

seeping into buildings.

Gas cartridges are

registered for the control of burrowing rodents and are

available from garden supply centers, hardware stores,

seed catalogs, or the USDA-APHIS-ADC program. Chipmunk

burrows may have to be enlarged to accommodate the

commercially or federally produced gas cartridges. Gas

cartridges should not be used under or around buildings

or near fire hazards since they burn with an open flame

and produce a tremendous amount of heat. Carbon monoxide

and carbon dioxide gases are produced while the

cartridges burn; thus, the rodents die from

asphyxiation.

Trapping

Trapping is the most practical method of eliminating

chipmunks in most home situations. Live-catch wire-mesh

traps or common rat snap traps can be used to catch

chipmunks. Common live-trap models include the Tomahawk

(Nos. 102, 201) and Havahart (Nos. 0745, 1020, 1025)

traps. Check the Supplies and Materials section for

additional manufacturers of live-catch traps.

A variety of baits can be

used to lure chipmunks into live traps, including peanut

butter, nutmeats, pumpkin or sunflower seeds, raisins,

prune slices, or common breakfast cereal grains. Place

the trap along the pathways where chipmunks have been

seen frequently. The trap should be securely placed so

there is no movement of the trap prematurely when the

animal enters. Trap movement may prematurely set off the

trap and scare the chipmunk away. A helpful tip is to

“prebait” the trap for 2 to 3 days by wiring the trap

doors open. This will condition the chipmunk to

associate the new metal object in its territory with the

new free food source. Set the trap after the chipmunk is

actively feeding on the bait in and around the trap.

Live traps can be purchased from local hardware stores,

department stores, pest control companies, or rented

from local animal shelters.

Check traps frequently to

remove captured chipmunks and release any nontarget

animals caught in them. Avoid direct contact with

trapped chipmunks. Transport and release livetrapped

chipmunks several miles from the point of capture (in

areas where they will not bother someone else), or

euthanize by placing in a carbon dioxide chamber.

Common rat snap traps can

be used to kill chipmunks if these traps are isolated

from children, pets, or wildlife. They can be set in the

same manner as live traps but hard baits should be tied

to the trap trigger. Prebait snap traps by not setting

the trap until the animal has been conditioned to take

the bait without disturbance for 2 to 3 days. Small

amounts of extra bait may be placed around the traps to

make them more attractive. Set the snap traps

perpendicular to the chipmunk’s pathway or in pairs

along travel routes with the triggers facing away from

each other. Set the trigger arm so that the trigger is

sensitive and easily sprung.

To avoid killing songbirds

in rat snap traps, it is advisable to place the traps

under a small box with openings that allow only

chipmunks access to the baited trap. The box must allow

enough clearance so the trap operates properly. Conceal

snap traps that are set against structures by leaning

boards over them. Small amounts of bait can be placed at

the openings as an attractant.

Shooting

Where shooting is legal, use a small-gauge shotgun

or a .22-caliber rifle with bird shot or C.B. cap loads.

Chipmunks are nervous and alert, so they make difficult

targets. The best time to attempt shooting is on bright

sunny days during the early morning.

Economics of Damage and Control

The majority of chipmunk

damage involves minimal economic loss (under $200).

Homeowners report that chipmunks are quite destructive

when it comes to their burrowing activities around

structures. This damage warrants an investment in

control to protect structural integrity of stairs,

patios, and foundations. Their consumption of seeds,

flower bulbs, fruit, and vegetables is often a nuisance.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all

the USDA-APHIS-ADC wildlife biologists who provided

information on chipmunks pertinent to their locality.

Kathleen LeMaster and Dee Anne Gillespie provided

technical assistance.

Figure 1 from Schwartz and

Schwartz (1981).

Figure 2 from Burt and

Grossenheider (1976).

For

Additional Information

Bennett, G. W., J. M.

Owens, and R. M. Corrigan. 1988. Truman’s scientific

guide to pest control operations. Purdue Univ./ Edgell

Commun. Duluth, Minnesota. 539 pp.

Burt, W. H., and R. P.

Grossenheider. 1976. A field guide to the mammals.

Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. 289 pp.

Corrigan, R. M., and D. E.

Williams. 1988. Chipmunks. ADC-2 leaflet, Coop. Ext.

Serv., Purdue Univ., West Lafayette, Indiana. in coop.

with the US Dept. Agric. 2 pp.

Dudderar, G. 1977.

Chipmunks and ground squirrels. Ext. Bull. E-867,

Michigan State Univ., Lansing, Michigan. 1 p.

Eadie, W. R. 1954. Animal

control in field, farm, and forest. The Macmillan Co.,

New York. 257 pp.

Gunderson, H. L., and J.

R. Beer. 1953. The mammals of Minnesota. Univ. Minnesota

Press. Minneapolis. 190 pp.

Hoffmeister, D. F., and C.

O. Mohr. 1957. A fieldbook of Illinois mammals. Nat.

Hist. Surv. Div. Urbana, Illinois. 233 pp.

Marsh, R. E., and W. E.

Howard. 1990. Vertebrate pests. Pages 771-831 in A.

Mallis ed., Handbook of pest control. 7th ed. Franzak

and Foster Co. Cleveland, Ohio.

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri. The Univ.

Missouri Press. Columbia. 356 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom; Robert

M. Timm; Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

David E.

Williams State Director USDA-APHIS-Animal Damage Control

Lincoln, Nebraska 68501

Robert M. Corrigan Staff Specialist Vertebrate Pest

Management Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana

47907

|