|

|

|

|

|

RODENTS: Beavers |

|

|

Identification

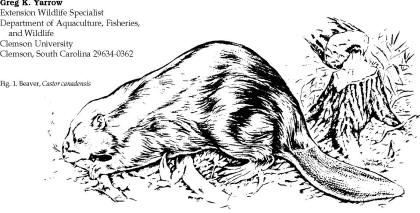

The

beaver (Castor canadensis, Fig. 1) is the largest North

American rodent. Most adults weigh from 35 to 50 pounds

(15.8 to 22.5 kg), with some occasionally reaching 70 to

85 pounds (31.5 to 38.3 kg). Individuals have been known

to reach over 100 pounds (45 kg). The beaver is a stocky

rodent adapted for aquatic environments. Many of the

beaver’s features enable it to remain submerged for long

periods of time. It has a valvular nose and ears, and

lips that close behind the four large incisor teeth.

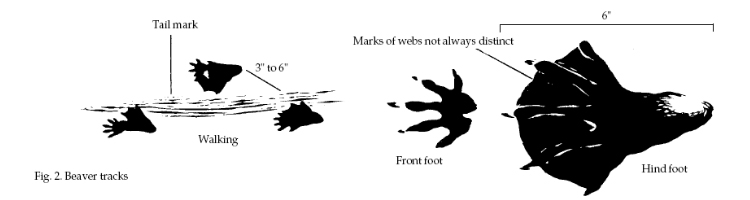

Each of the four feet have five digits, with the hind

feet webbed between digits and a split second claw on

each hind foot. The front feet are small in comparison

to the hind feet (Fig. 2). The underfur is dense and

generally gray in color, whereas the guard hair is long,

coarse and ranging in color from yellowish brown to

black, with reddish The

beaver (Castor canadensis, Fig. 1) is the largest North

American rodent. Most adults weigh from 35 to 50 pounds

(15.8 to 22.5 kg), with some occasionally reaching 70 to

85 pounds (31.5 to 38.3 kg). Individuals have been known

to reach over 100 pounds (45 kg). The beaver is a stocky

rodent adapted for aquatic environments. Many of the

beaver’s features enable it to remain submerged for long

periods of time. It has a valvular nose and ears, and

lips that close behind the four large incisor teeth.

Each of the four feet have five digits, with the hind

feet webbed between digits and a split second claw on

each hind foot. The front feet are small in comparison

to the hind feet (Fig. 2). The underfur is dense and

generally gray in color, whereas the guard hair is long,

coarse and ranging in color from yellowish brown to

black, with reddish brown the most common coloration. The prominent tail is

flattened dorsoventrally, scaled, and almost hairless.

It is used as a prop while the beaver is sitting upright

(Fig. 3) and for a rudder when swimming. Beavers also

use their tail to warn others of danger by abruptly

slapping the surface of the water. The beaver’s large

front (incisor) teeth, bright orange on the front, grow

continuously throughout its life. These incisors are

beveled so that they are continuously sharpened as the

beaver gnaws and chews while feeding, girdling, and

cutting trees. The only way to externally distinguish

the sex of a beaver, unless the female is lactating, is

to feel for the presence of a baculum (a bone in the

penis) in males and its absence in females.

brown the most common coloration. The prominent tail is

flattened dorsoventrally, scaled, and almost hairless.

It is used as a prop while the beaver is sitting upright

(Fig. 3) and for a rudder when swimming. Beavers also

use their tail to warn others of danger by abruptly

slapping the surface of the water. The beaver’s large

front (incisor) teeth, bright orange on the front, grow

continuously throughout its life. These incisors are

beveled so that they are continuously sharpened as the

beaver gnaws and chews while feeding, girdling, and

cutting trees. The only way to externally distinguish

the sex of a beaver, unless the female is lactating, is

to feel for the presence of a baculum (a bone in the

penis) in males and its absence in females.

Range

Beavers

are found throughout North America, except for the

arctic tundra, most of peninsular Florida, and the

southwestern desert areas (Fig. 4). The species may be

locally abundant wherever aquatic habitats are found. Beavers

are found throughout North America, except for the

arctic tundra, most of peninsular Florida, and the

southwestern desert areas (Fig. 4). The species may be

locally abundant wherever aquatic habitats are found.

Habitat

Beavers have a relatively

long life span, with individuals known to have lived to

21 years. Most, however, do not live beyond 10 years.

The beaver is unparalleled at dam building and can build

dams on fast-moving streams as well as slow-moving ones.

They also build lodges and bank dens, depending on the

available habitat. All lodges and bank dens have at

least two entrances and may have four or more. The lodge

or bank den is used primarily for raising young,

sleeping, and food storage during severe weather (Fig.

5).

Fig. 5. Cross section of a

beaver lodge.

The size and species of

trees the beaver cuts is highly variable — from a 1-inch

(2.5-cm) diameter at breast height (DBH) softwood to a

6-foot (1.8-m) DBH hardwood. In some areas beavers

usually cut down trees up to about 10 inches (25 cm) DBH

and merely girdle or partially cut larger ones, although

they often cut down much larger trees. Some beavers seem

to like to girdle large pines and sweet-gums. They like

the gum or storax that seeps out of the girdled area of

sweet-gum and other species.

An important factor about

beavers is their territoriality. A colony generally

consists of four to eight related beavers, who resist

additions or outsiders to the colony or the pond. Young

beavers are commonly displaced from the colony shortly

after they become sexually mature, at about 2 years old.

They often move to another area to begin a new pond and

colony. However, some become solitary hermits inhabiting

old abandoned ponds or farm ponds if available.

Beavers have only a few

natural predators aside from humans, including coyotes,

bobcats, river otters, and mink, who prey on young

kittens. In other areas, bears, mountain lions, wolves,

and wolverines may prey on beavers. Beavers are hosts

for several ectoparasites and internal parasites

including nematodes, trematodes, and coccidians. Giardia

lamblia is a pathogenic intestinal parasite transmitted

by beavers, which has caused human health problems in

water supply sys-tems. The Centers for Disease Control

have recorded at least 41 outbreaks of waterborne

Giardiasis, affecting more than 15,000 people. For more

information about Giardiasis, see von Oettingen (1982).

Damage and

Damage Identification

The

habitat modification by beavers, caused primarily by dam

building, is often beneficial to fish, furbearers,

reptiles, amphibians, waterfowl, and shorebirds.

However, when this modification comes in conflict with

human objectives, the impact of damage may far outweigh

the benefits. The

habitat modification by beavers, caused primarily by dam

building, is often beneficial to fish, furbearers,

reptiles, amphibians, waterfowl, and shorebirds.

However, when this modification comes in conflict with

human objectives, the impact of damage may far outweigh

the benefits.

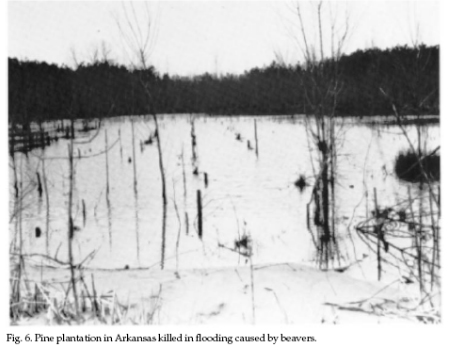

Most of the damage caused

by beavers is a result of dam building, bank burrowing,

tree cutting, or flooding. Some southeastern states

where beaver damage is extensive have estimated the cost

at $3 million to $5 million dollars annually for timber

loss; crop losses; roads, dwellings, and flooded

property; and other damage. In some states, tracts of

bottomland hardwood timber up to several thousand acres

(ha) in size may be lost because of beaver. Some unusual

cases observed include state highways flooded because of

beaver ponds, reservoir dams destroyed by bank den

burrows collapsing, and train derailments caused by

continued flooding and burrowing. Housing developments

have been threatened by beaver dam flooding, and

thousands of acres (ha) of cropland and young pine

plantations have been flooded by beaver dams (Fig. 6).

Road ditches, drain pipes, and culverts have been

stopped up so badly that they had to be dynamited out

and replaced. Some bridges have been destroyed because

of beaver dam-building activity. In addition, beavers

threaten human health by contaminating water supplies

with Giardia.

Identifying beaver damage

generally is not difficult. Signs include dams;

dammed-up culverts, bridges, or drain pipes resulting in

flooded lands, timber, roads, and crops; cut-down or

girdled trees and crops; lodges and burrows in ponds,

reservoir levees, and dams. In large watersheds, it may

be difficult to locate bank dens. However, the limbs,

cuttings, and debris around such areas as well as dams

along tributaries usually help pinpoint the area.

Legal

Status

It is almost impossible as

well as cost-prohibitive to exclude beavers from ponds,

lakes, or impoundments. If the primary reason for

fencing is to exclude beavers, fencing of large areas is

not practical. Fencing of culverts, drain pipes, or

other structures can sometimes prevent damage, but

fencing can also promote damage, since it provides

beavers with construction material for dams. Protect

valuable trees adjacent to waterways by encircling them

with hardware cloth, woven wire, or other metal

barriers. Construction of concrete spillways or other

permanent structures may reduce the impact of beavers.

Cultural Methods

Because beavers usually

alter or modify their aquatic habitat so extensively

over a period of time, most practices generally thought

of as cultural have little impact on beavers. Where

feasible, eliminate food, trees, and woody vegetation

that is adjacent to beaver habitat. Continual

destruction of dams and removal of dam construction

materials daily will (depending on availability of

construction materials) sometimes cause a colony or

individual beavers to move to another site. They might,

however, be even more troublesome at the new location.

The use of a three-log

drain or a structural device such as wire mesh culverts

(Roblee 1983) or T-culvert guards (Roblee 1987) will

occasionally cause beavers to move to other areas. They

all prevent beavers from controlling water levels.

However, once beavers have become abundant in a

watershed or in a large contiguous area, periodic

reinvasions of suitable habitat can be expected to

occur. Three-log drains have had varying degrees of

success in controlling water levels in beaver

impoundments, especially if the beaver can detect the

sound of falling water or current flow. All of these

devices will stimulate the beavers to quickly plug the

source of water drainage.

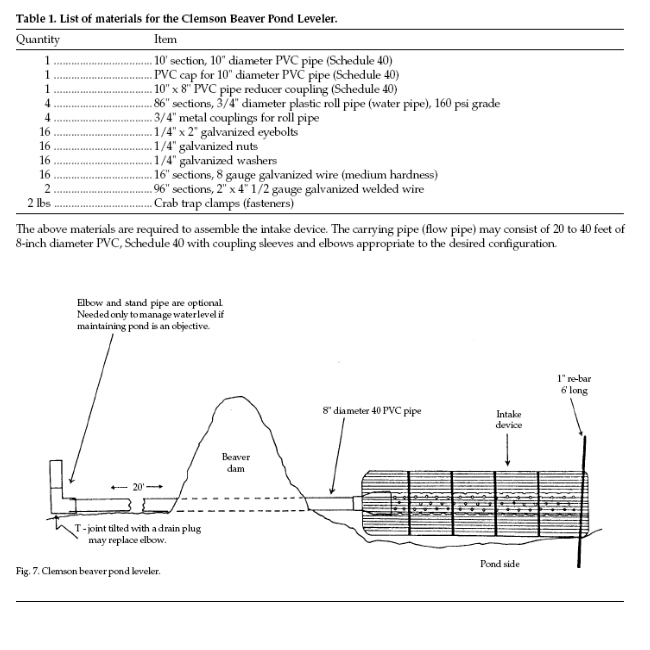

A new device for

controlling beaver impoundments and keeping blocked

culverts open is the Clemson beaver pond leveler. It has

proven effective in allowing continual water flow in

previously blocked culverts/drains and facilitating the

manipulation of water levels in beaver ponds for

moist-soil management for waterfowl (Wood and Woodward

1992) and other environmental or aesthetic purposes. The

device (Fig. 7) consists of a perforated PVC pipe that

is encased in heavy-gauge hog wire. This part is placed

upstream of the dam or blocked culvert, in the main run

or deepest part of the stream. It is connected to

nonperforated sections of PVC pipe which are run through

the dam or culvert to a water control structure

downstream. It is effective because the beavers cannot

detect the sound of falling or flowing water as the pond

or culvert drains; therefore, they do not try to plug

the pipe. The Clemson beaver pond leveler works best in

relatively flat terrain where large volumes of water

from watersheds in steep terrain are not a problem.

Repellents

There are no chemical repellents registered for

beavers. Past research efforts have tried to determine

the effectiveness of potential repellent materials;

however, none were found to be effective,

environmentally safe, or practical. One study in Georgia

(Hicks 1978) indicated that a deer repellent had some

potential benefit. Other studies have used a combination

of dam blowing and repellent soaked (Thiram 80 and/or

paradichlorobenzene) rags to discourage beavers with

varying degrees of success (Dyer and Rowell 1985).

Additional research is

needed on repellents for beaver damage prevention.

Toxicants

None are registered. Research efforts have been

conducted, however, to find effective, environmentally

safe and practical toxicants. Currently there are none

that meet these criteria.

Fumigants

None are registered.

Trapping

The use of traps in most situations where beavers

are causing damage is the most effective, practical, and

environmentally safe method of control. The

effectiveness of any type of trap for beaver control is

dependent on the trapper’s knowledge of beaver habits,

food preferences, ability to read beaver signs, use of

the proper trap, and trap placement. A good trapper with

a dozen traps can generally trap all the beavers in a

given pond (behind one dam) in a week of trap nights.

Obviously in a large watershed with several colonies,

more trapping effort will be required. Most anyone with

trapping experience and some outdoor “savvy” can become

an effective beaver trapper in a short time. In an area

where beavers are common and have not been exposed to

trapping, anyone experienced in trapping can expect good

success. Additional expertise and improved techniques

will be gained through experience.

A variety of trapping

methods and types of traps are effective for beavers,

depending on the situation. Fish and wildlife agency

regulations vary from state to state. Some types of

traps and trapping methods, although effective and legal

in some states, may be prohibited by law in other

states. Individual state regulations must be reviewed

annually before beginning a trapping program.

In some states where

beavers have become serious economic pests, special

regulations and exemptions have been passed to allow for

increased control efforts. For example, some states

allow trapping and snaring of beavers and other control

measures throughout the year. Others, however, prohibit

trapping except during established fur trapping seasons.

Some states allow exemptions for removal of beavers only

on lands owned or controlled by persons who are

suffering losses. In some states a special permit is

required from the state fish and wildlife agency.

Of the variety of traps

commonly allowed for use in beaver control, the Conibear®

type, No. 330, is one of the most effective (Fig. 8).

Not all trappers will agree that this type of trap is

the most effective; however, it is the type most

commonly used by professional trappers and others who

are principally trapping beavers. This trap kills

beavers almost instantly. When properly set, the trap

also prevents any escape by a beaver, regardless of its

size. Designed primarily for water use, it is equally

effective in deep and shallow water. Only one trap per

site is generally necessary, thus reducing the need for

extra traps. The trap exerts tremendous pressure and

impact when tripped. Appropriate care must be exercised

when setting and placing

the

trap. Care should also be taken when using the Conibear®

type traps in urban and rural areas where pets

(especially dogs) roam free. Use trap sets where the

trap is placed completely underwater. the

trap. Care should also be taken when using the Conibear®

type traps in urban and rural areas where pets

(especially dogs) roam free. Use trap sets where the

trap is placed completely underwater.

Some additional equipment

will be useful: an axe, hatchet, or large cutting tool;

hip boots or waders; wire; and wire cutters. With the

Conibear®-type trap, some individuals use a device or

tool called “setting tongs.” Others use a piece of 3/8-

or 1/2-inch (9- or 13mm) nylon rope. Most individuals

who are experienced with these traps use only their

hands. Regardless of the techniques used to set the

trap, care should be exercised.

Earlier models of the

Conibear® type of trap came with round, heavy steel

coils which were dangerous to handle unless properly

used in setting the trap. They are not necessary to

safely set the trap. However, the two safety hooks, one

on each spring, must be carefully handled as each spring

is depressed, as well as during trap placement. On newer

models an additional safety catch (not attached to the

springs) is included for extra precaution against

inadvertent spring release. The last step before leaving

a set trap is to lift the safety hook attached to each

spring and slide the safety hook back from the trap

toward the spring eye, making sure to keep hands and

feet safely away from the center of the trap. If the

extra (unattached) safety catch is used, it should be

removed before the safety hooks that are attached to the

springs to keep it from getting in the way of the

movement of the safety hooks.

Conibear®-type

traps are best set while on solid ground with dry hands.

Once the springs are depressed and the safety hooks in

place, the trap or traps can be carried into the water

for proper placement. Stakes are needed to anchor the

trap down. In most beaver ponds and around beaver dams,

plenty of suitable stakes can be found. At least two

strong stakes, preferably straight and without forks or

snags, should be chosen to place through each spring eye

(Fig. 8). Additional stakes may be useful to put between

the spring arms and help hold the trap in place. Do not

place stakes on the outside of spring arms. Aside from

serving to hold the trap in place, these stakes also

help to guide the beaver into the trap. Where needed,

they are also useful in holding a dive stick at or just

beneath the water surface (Fig. 9). If necessary, the

chain and circle attached to one spring eye can be

attached to another stake. In deep water sets, a chain

with an attached wire should be tied to something at or

above the surface so the trapper can retrieve the trap.

Otherwise the trap may be lost. Conibear®-type

traps are best set while on solid ground with dry hands.

Once the springs are depressed and the safety hooks in

place, the trap or traps can be carried into the water

for proper placement. Stakes are needed to anchor the

trap down. In most beaver ponds and around beaver dams,

plenty of suitable stakes can be found. At least two

strong stakes, preferably straight and without forks or

snags, should be chosen to place through each spring eye

(Fig. 8). Additional stakes may be useful to put between

the spring arms and help hold the trap in place. Do not

place stakes on the outside of spring arms. Aside from

serving to hold the trap in place, these stakes also

help to guide the beaver into the trap. Where needed,

they are also useful in holding a dive stick at or just

beneath the water surface (Fig. 9). If necessary, the

chain and circle attached to one spring eye can be

attached to another stake. In deep water sets, a chain

with an attached wire should be tied to something at or

above the surface so the trapper can retrieve the trap.

Otherwise the trap may be lost.

Trap Sets. There are many

sets that can be made with a Conibear®-type trap (for

example, dam sets, slide sets, lodge sets, bank den

sets, “run”/trail sets, under log/dive sets, pole sets,

under ice sets, deep water sets, drain pipe sets),

depending on the trapper’s capability and ingenuity. In

many beaver ponds, however, most beavers can be trapped

using dam sets, lodge or bank den sets, sets in

“runs”/trails, dive sets or sets in slides entering the

water from places where beavers are feeding. Beavers

swim both at the surface or along the bottom of ponds,

depending on the habitat and water depth. Beavers also

establish runs or trails which they habitually use in

traveling from lodge or den to the dam or to feeding

areas, much like cow trails in a pasture.

Place traps directly

across these runs, staked to the bottom (Fig. 10).

Use a good stake or

“walking staff’ when wading in a beaver pond to locate

deep holes, runs, or trails. This will prevent stepping

off over waders or hip boots in winter, and will help

ward off cottonmouth snakes in the summer. The staff can

also help locate good dive holes under logs as you walk

out runs or trails. In older beaver ponds, particularly

in bottomland swamps, it is not uncommon to find runs

and lodge or bank den entrances where the run or hole is

2 to 3 feet (0.6 to 0.9 m) below the rest of the

impoundment bottom.

To stimulate nighttime

beaver movement, tear a hole in a beaver dam and get the

water moving out of a pond. Beavers quickly respond to

the sound of running water as well as to the current

flow. Timing is also important if you plan to make dam

sets. Open a hole in the dam about 18 inches to 2 feet

(46 to 60 cm) wide and 2 to 3 feet (60 to 90 cm) below

the water level on the upper side of the dam in the

morning. This will usually move a substantial amount of

water out of the pond before evening (Fig. 11). Set

traps in front of the dam opening late that same

evening. Two problems can arise if you set a trap in the

morning as soon as a hole is made: (1) by late evening,

when the beavers become active, the trap may be out of

the water and ineffective; or (2) a stick, branch, or

other debris in the moving water may trip the trap,

again rendering it ineffective.

The best dam sets are made

about 12 to 18 inches (30.8 to 45.7 cm) in front of the

dam itself. Using stakes or debris on either side of the

trap springs, create a funnel to make the beaver go into

the jaws of the trap. Always set the trigger on the

Conibear®-type trap in the first notch to prevent debris

from tripping it before the beaver swims into the trap.

The two heavy-gauge wire trippers can be bent outward

and the trigger can be set away from the middle if

necessary, to keep debris from tripping the trap. This

can also keep small beaver or possibly fish or turtles

from springing the trap. Double-spring leghold traps

have been used for hundreds of years and are still very

effective when properly used by skilled trappers. Use at

least No. 3 double (long) spring or coil spring type

leghold traps or traps of equivalent size jaw spread and

strength. Use a drowning set attachment with any leghold

trap (Fig. 12). As the traps are tripped, the beaver

will head for the water. A weight is used to hold the

trapped beaver underwater so that it ultimately drowns.

Some trappers stake the wire in deep water to accomplish

drowning. If leghold traps are not used in a manner to

accomplish drowning, there is a good likelihood that

legs or toes will be twisted off or pulled loose,

leaving an escaped, trap-wise beaver.

Placement is even more

critical with leghold traps than with the Conibear®-type.

Place leghold traps just at the water’s edge, slightly

underwater, with the pan, jaws, and springs covered

lightly with leaves or debris or pressed gently into the

pond bottom in soft mud. Make sure there is a cavity

under the pan so that when the beaver’s foot hits the

pan, it will trigger the trap and allow the jaws to snap

closed. Place traps off-center of the trail or run to

prevent “belly pinching” or missing the foot or leg.

With some experience, beaver trappers learn to make sets

that catch beavers by a hind leg rather than a front

leg. The front leg is much smaller and easier to twist

off or pull out.

Sometimes it’s wise, when

using leghold traps, to make two sets in a slide, run,

dam, or feeding place to increase trapping success and

remove beavers more quickly. In some situations, a

combination of trapping methods can shorten trapping

time and increase success.

Trappers have come up with

unique methods of making drown sets. One of the simplest

and most practical is a slide wire with a heavy weight

attached to one end, or with an end staked to the bottom

in 3 or more feet (>0.9 m) of water. The other end of

the wire is threaded through a hole in one end of a

small piece of angle iron. The trap chain is attached to

a hole in the other end of the angle. The end of the

wire is then attached to a tree or stake driven into the

bank (Fig. 13). When the beaver gets a foot or leg in

the trap, it immediately dives back into the water. As

the angle slides down the wire, it prevents the beaver

from reaching the surface. The angle iron piece will not

slide back up the wire and most often bends the wire as

the beaver struggles, thus preventing the beaver from

coming up for air. Trappers should be prepared to

quickly and humanely dispatch a beaver that is caught in

a trap and has not drowned.

The leghold trap set in

lodges or bank dens is also effective, especially for

trapping young beavers. Place the set on the edge of the

hole where the beaver first turns upward to enter the

lodge or den, or place it near the bottom of the dive

hole. Keep the jaws and pan off of the bottom by pulling

the springs backward so that a swimming foot will trip

the pan. Stake the set close to the bottom or wire the

trap to a log or root on the bottom, to avoid the need

for drowning weights, wires, and angle iron pieces.

Generally, more time and expertise is necessary to make

effective sets with leghold traps and snares than is

required with the Conibear®-type trap.

Use scent or freshly cut

cottonwood, aspen, willow, or sweetgum limbs to entice

beaver to leghold trap sets. Bait or scent is especially

useful around scent mounds and up slides along the banks

or dams. Most trappers who use Conibear®-type traps do

not employ baits or scent, although they are

occasionally helpful. In some states it is illegal to

use bait or scent.

Several other types of

traps can be used, including basket/suitcase type live

traps. These are rarely used, however, except by

professionals in urban areas where anti-trap sentiment

or other reasons prevent the killing of beavers. These

traps are difficult and cumbersome to use, and will not

be further discussed here for use in beaver damage

control. Any type of traps used for beavers or other

animals should be checked daily.

Snaring can be a very

cost-effective method for capturing beavers. Snaring

equipment costs far less than trapping equipment and is

more convenient to use in many situations. In addition,

beavers can be captured alive by snaring and released

elsewhere if desired.

Snare placement is similar

to trap placement. First, look for runways and fresh

sign that indicate where beaver activities are focused.

Find a suitable anchor such as a large tree, log, or

root within 10 feet (3 m) of the runway where the snare

will be set. If necessary, anchor snares by rods driven

into the ground, but this is more time consuming and

less secure. Attach three 14-gauge wires to the anchor

so that each can swivel freely. Cut each wire to length

so they reach about 1 foot (30 cm) past the runway.

Twist the wires together to form a strong braided anchor

cable. Drive a supporting stake into the ground near the

runway and wrap the free end of the anchor cable around

it twice. Prepare a new, dyed, No. 4 beaver or coyote

snare, consisting of 42 inches (107 cm) of 3/32-inch

(2.4-mm) steel cable with an attached wire swivel and

slide lock. Twist the free ends of the three anchor

wires around the wire swivel on the end of the snare

cable. Wrap the longest anchor wire around the base of

the wire swivel and crimp it onto the snare cable about

2 inches (5 cm) from the swivel. Use both the stake and

the supporting anchor wire to suspend a full-sized loop

about 4 inches (10 cm) above the runway. If necessary,

use guide sticks or other natural debris to guide beaver

into the snare.

The described snare set is

very common, but there are several variations and sets

that can be used. Snares are frequently placed under

logs, near bank dens, and next to castor mounds.

Drowning sets can be made using underwater anchors,

slide cables, and slide locks.

Snares should be checked

at least every 24 hours. Dispatch snared beavers with a

sharp blow or shot to the head. Beavers can be

chemically immobilized and transported to suitable sites

for release if desired.

Snares must be used with

great care to avoid capturing nontarget animals. Avoid

trails or areas that are used by livestock, deer, or

dogs. Check with your local wildlife agency for

regulations associated with trapping and snaring.

Snaring is not allowed in some states.

For more information about

the use of snares see A Guide to Using Snares for Beaver

Capture (Weaver et al. 1985) listed at the end of this

chapter.

Fig. 14. Conibear® in

culvert set. When beavers are stopping up a drainage

culvert, (1) clean out the pipe to get water flowing

through freely; (2) set the trap at the level of the

drain pipe entrance, but far enough away to clear the

culvert when the beaver enters; (3) put stakes on either

side to make the beaver enter the trap correctly.

Shooting

In some states, because of the extent of damage

caused by beavers, regulations have been relaxed to

allow shooting. Some states even allow the use of a

light at night to spot beavers while shooting. Before

attempting to shoot beavers, check regulations, and if

applicable, secure permits and notify local law

enforcement personnel of your intentions. Beavers are

most active from late afternoon to shortly after

daybreak, depending on the time of year. They usually

retire to a lodge or bank den for the day. Therefore, if

night shooting is not permitted, the early evening and

early morning hours are most productive. Choice of

weapons depends on the range and situation. Most

shooting is done with a shotgun at close range at night.

Shooting alone is generally not effective in eliminating

all beaver damage in an area. It can, however, be used

to quickly reduce a population.

Other Methods

Because of the frustration and damage beavers have

caused landowners, almost every control method

imaginable has been tried. These range from dynamiting

lodges during midday to using snag-type fish hooks in

front of dams, road culverts, and drain pipes. Such

methods rarely solve a damage problem, although they may

kill a few beavers and nontarget species. They are not

recommended by responsible wildlife professionals. One

method used occasionally along streams prone to flooding

is shooting beavers that have been flooded out of lodges

and bank dens. This method is often dangerous and rarely

solves a damage problem.

Economics of Damage and Control

The economics of beaver damage is somewhat dependent

on the extent of the damage before it has been

discovered. Some beaver damage problems are intensive,

such as damage The most important point is that damage

control should begin as soon as it is evident that a

beaver problem exists or appears likely to develop. Once

beaver colonies become well established over a large

contiguous area, achieving control is difficult and

costly. One of the most difficult situations arises when

an adjacent landowner will not allow the control of

beavers on their property. In this situation, one can

expect periodic reinvasions of beavers and continual

problems with beaver damage, even if all beavers are

removed from the property where control is practiced.

Although benefits of

beavers and beaver ponds are not covered in depth here,

there are a number. Aside from creating fish, waterfowl,

furbearer, shorebird, reptile, and amphibian habitat,

the beaver in many areas is an important fur resource,

as well as a food resource. For those who have not yet

tried it, beaver meat is excellent table fare if

properly prepared, and it can be used whether the pelts

are worth skinning or not. It also makes good bait for

trapping large predators.

Proper precautions, such

as wearing rubber gloves, should be taken when skinning

or eviscerating beaver carcasses, to avoid contracting

transmissible diseases such as tuleremia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank, for their cooperation, past and

present employees of the Fish and Wildlife Service, US

Department of the Interior, county extension agents with

the Cooperative Extension Service in various states,

cooperators with the USDA-APHIS-ADC program in a number

of states, and the many landowners with beaver problems

across the South. The experience gained in efforts to

assist landowners with wildlife damage problems provided

most of the information contained herein.

Figures 1, 2, 4 and 5 from

Schwartz and Schwartz (1981).

Figure 3 by Jill Sack

Johnson.

Figure 6 and 7 by the

authors.

Figures 8 through 12 and

14 from Miller (1978).

Figure 13 by Jill Sack

Johnson after Miller (1978).

For

Additional Information

Arner, D. H., and J. S.

Dubose. 1982. The impact of the beaver on the

environment and economics in Southeastern United States.

Trans. Int. Congr. Game Biol. 14:241-247.

Byford, J. L. 1976.

Beavers in Tennessee: control, utilization and

management. Tennessee Coop. Ext. Serv., Knoxville. Pub.

687. 15 pp.

Dyer, J. M., and C. E.

Rowell. 1985. An investigation of techniques used to

discourage rebuilding of beaver dams demolished by

explosives. Proc. Eastern Wildl. Damage Control Conf.

2:97-102.

Hicks, J. T. 1978. Methods

of beaver control. Final Rep., Res. Proj. No. W-37-R,

Georgia Game Fish Div., Dep. Nat. Res. 3 pp.

Hill, E. H. 1974. Trapping

beaver and processing their fur. Alabama Coop. Wildl.

Res. Unit, Agric. Exp. Stn., Auburn Univ. Pub. No. 1. 10

pp.

Miller, J. E. 1972.

Muskrat and beaver control. Proc. Nat. Ext. Wildl.

Workshop, 1:35-37.

Miller, J. E. 1978. Beaver

— friend or foe. Arkansas Coop. Ext. Serv., Little Rock.

Cir. 539. 15 pp.

Roblee, K. J. 1983. A wire

mesh culvert for use in controlling water levels at

nuisance beaver sites. Proc. Eastern Wildl. Damage

Control Conf. 1:167-168.

Roblee, K. J. 1987.The use

of the T-culvert guard to protect road culverts from

plugging damage by beavers. Proc. Eastern Wildl. Damage

Control Conf. 3:25-33

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri, Rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp.

von Oettingen, S.L. 1982.

A survey of beaver in central Massachusetts for Giardia

lamblia. M.S. Thesis, Univ. Massachusetts, Amherst. 58

pp.

Weaver, K. M., D. H. Arner,

C. Mason, and J. J. Hartley. 1985. A guide to using

snares for beaver capture. South. J. Appl. For.

9(3):141-146.

Wood, G. W., and L. A.

Woodward. 1992. The Clemson beaver pond leveler. Proc.

Annu. Conf. Southeast Fish Wildl. Agencies.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom; Robert

M. Timm; Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

James E. Miller

Program Leader, Fish and Wildlife

USDA — Extension Service Natural Resources and Rural

Development Unit

Washington, DC 20250

|