|

|

|

|

|

RODENTS: Squirrels, Franklin, Richardson,

Columbian Washington and Townsend |

|

|

Fig. 1.

Franklin ground squirrel, Spermophilus franklinii

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

-

Exclusion

Limited usefulness.

-

Cultural Methods

Flood irrigation, forage removal, crop rotation, and

summer fallow may reduce populations and limit

spread.

-

Repellents

None are registered.

-

Toxicants

Zinc phosphide.

Chlorophacinone.

Diphacinone.

Note: Not all toxicants are registered for use in

every state. Check registration labels for

limitations within each state.

-

Fumigants

Aluminum phosphide. Gas cartridge.

-

Trapping

Box traps. Burrow-entrance traps. Leghold traps.

-

Shooting

Limited usefulness.

Identification

The Franklin ground

squirrel (Spermophilus franklinii, Fig. 1) is a rather

drab grayish brown. Black speckling gives a spotted or

barred effect. Head and body average 10 inches (25.4 cm)

with a 5- to 6-inch (12.7- to 15.2-cm) tail. Adults

weigh from 10 to 25 ounces (280 to 700 g).

The Richardson ground

squirrel (S. richardson) is smaller and lighter colored

than the Franklin. Some are dappled on the back. The

squirrel’s body measures about 8 inches (20.3 cm) with a

tail of from 2 to 4 inches (5 to 10 cm). Adults weigh

from 11 to 18 ounces (308 to 504 g).

The Columbian ground

squirrel (S. columbianus) is easily distinguished from

others in its range by its distinctive coloration.

Reddish brown (rufous) fur is quite evident on the nose,

forelegs, and hindquarters. The head and body measure 10

to 12 inches (25.4 to 30.5 cm) in length with a 3- to

5-inch (7.6-to 12.7-cm) tail. An average adult weighs

more than 16 ounces (454 g).

The Washington ground

squirrel (S. washingtoni) has a small smoky-gray flecked

body with dappled whitish spots. The tail is short with

a blackish tip. This squirrel is similar to Townsend and

Belding squirrels except the latter have no spots. Head

and body are about 6 to 7 inches long (15.2 to 18 cm);

the tail 1.3 to 2.5 inches long (3.4 to 6.4 cm); and

adults weigh 6 to 10 ounces (168 to 280 g).

The Townsend ground

squirrel’s (S. townsendi) head and body range in length

from 5.5 to 7 inches (14 to 18 cm). It has a short

bicolored tail about 1.3 to 2.3 inches (3 to 6 cm) long,

and weighs approximately 6 to 9 ounces (168 to 252 g).

The body is smoky-gray washed with a pinkish-buff. The

belly and flanks are whitish.

Other species not

described here because they cause few economic problems

are Idaho (S. brunneus), Uinta (S. armatus), Mexican (S.

mexicanus), Spotted (S. spilosoma), Mohave (S.

mohavensis), and roundtail (S. tereticaudus) ground

squirrels.

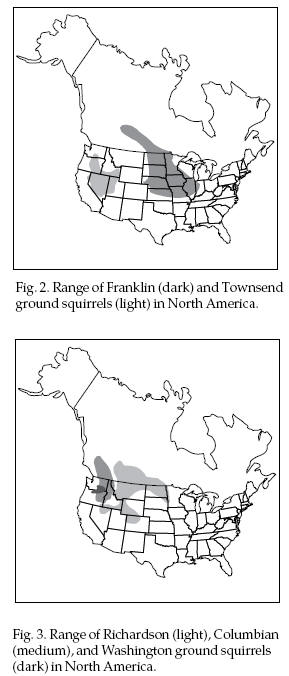

Range Range

Ground squirrels are

common throughout the western two-thirds of the North

American continent. Most are common to areas of open

sagebrush and grasslands and are often found in and

around dryland grain fields, meadows, hay land, and

irrigated pastures. Details of each species range, which

overlap occasionally, are shown in figures 2 and 3.

Food Habits

Ground squirrels eat a

wide variety of food. Most prefer succulent green

vegetation (grasses, forbs, and even brush) when

available, switching to dry foods, such as seeds, later

in the year. The relatively high nutrient and oil

content of the seeds aids in the deposition of fat

necessary for hibernation. Most store large quantities

of food in burrow caches. Some species, like the

Franklin, eat a greater amount of animal matter,

including ground-nesting bird eggs. Insects and other

animal tissue may comprise up to one-fourth of their

diet.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Ground squirrels construct

and live in extensive underground burrows, sometimes up

to 6 feet (2 m) deep, with many entrances. They also use

and improve on the abandoned burrows of other mammals

such as prairie dogs and pocket gophers. Most return to

their nests of dried vegetation within the burrows at

night, during the warmest part of summer days, and when

they are threatened by predators, such as snakes,

coyotes, foxes, weasels, badgers, and raptors.

The squirrels generally

enter their burrows to estivate, escaping the late

summer heat. They hibernate during the coldest part of

the winter. Males usually become active above ground 1

to 2 weeks before the females in the spring, sometimes

as early as late February or early March. A few may be

active above ground throughout the year. Breeding takes

place immediately after emergence. The young are born

after a 4-to 5-week gestation period with 2 to 10 young

per litter. Generally only 1 litter is produced each

year. Densities of the ground squirrel populations can

range from 2 to 20 or more per acre (5 to 50/ha).

Damage and Damage Identification

High populations of ground

squirrels may pose a serious pest problem. The squirrels

compete with livestock for forage; destroy food crops,

golf courses, and lawns; and can be reservoirs for

diseases such as plague. Their burrow systems have been

known to weaken and collapse ditch banks and canals,

undermine foundations, and alter irrigation systems. The

mounds of soil excavated from their burrows not only

cover and kill vegetation, but damage haying machinery.

In addition, some ground squirrels prey on the eggs and

young of ground-nesting birds or climb trees in the

spring to feed on new shoots and buds in orchards.

Legal Status

Ground squirrels generally

are unprotected. However, species associated with them,

such as black-footed ferrets, weasels, wolves, eagles,

and other carnivores may be protected. Local laws as

well as specific label restrictions should be consulted

before initiating lethal control measures.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Exclusion is impractical

in most cases because ground squirrels are able to dig

under or climb over most simple barriers. Structures

truly able to exclude them are prohibitively expensive

for most situations. Sheet metal collars are sometimes

used around tree trunks to prevent damage to the base of

the trees or to keep animals from climbing trees to eat

fruit or nut crops.

Cultural Methods/Habitat

Modification

Flood irrigation of hay

and pasture lands and frequent tillage of other crops

discourage ground squirrels somewhat. Squirrels,

however, usually adapt by building the major part of

their burrows at the margins of fields, where they have

access to the crop. During the early part of the season

they begin foraging from the existing burrow system into

the field until their comfort escape zone is exceeded.

When this zone is exceeded and as the litters mature in

the colony, tunnels will be extended into the feeding

area. Late in the summer or fall, tillage will destroy

these tunnels but will not disturb or destroy the

original system at the edge of the field.

Some research has been

conducted on the effect of tall vegetation on ground

squirrel populations and movements. The data, while

sketchy, indicate that the squirrels may move out of

tall vegetation stands to more open grass fields. The

addition of raptor (hawk, owl, and kestrel) nest boxes

and perches around the field border or throughout the

colony may reduce colony growth, but is not a reliable

damage control method.

Toxicants

Zinc phosphide and

anticoagulants are currently registered for ground

squirrel control. Since pesticide registrations vary

from state to state, check with your local extension,

USDA-APHIS-Animal Damage Control, or state department of

agriculture for use limitations. Additional restrictions

may be in effect for areas where endangered species have

been identified.

Zinc phosphide has been

used for several years to control ground squirrels. It

is a single-dose toxicant which, when used properly, can

result in mortality rates as high as 85% to 90%. If,

however, the targeted animals do not consume enough bait

for mortality to occur, they become sick, associate

their illness with the food source they have just

consumed, and are reluctant to return to the bait. This

is called “bait shyness.” Repeated baiting with the same

bait formulations is generally unsuccessful,

particularly when tried during the same year.

Prebaiting may increase

bait acceptance with treated grain baits. Prebaiting

means exposing squirrels to untreated grain bait several

days before using toxic grain. Conditioning the

squirrels to eating this new food improves the

likelihood of their eating a lethal dose of toxic grain.

Prebaiting often improves bait acceptance and,

therefore, control. The major disadvantage is the cost

of labor and materials for prebaiting.

Zinc phosphide is

classified as a Restricted Use Pesticide and as such,

can only be purchased or used with proper certification

from the state. Certification information can be

obtained from your local Cooperative Extension or state

department of agriculture office. Zinc phosphide can be

absorbed in small amounts through the skin. Rubber

gloves should be worn when handling the bait.

Use only fresh bait.

Spoiled or contaminated baits will not be eaten by

ground squirrels. Old bait may not be sufficiently toxic

to be effective. If zinc phosphide baits are more than a

few months old they should not be used, particularly if

they have not been stored in air-tight, sealed

containers, because they decompose with humidity in the

air.

Chlorophacinone and

diphacinone are two anticoagulant baits that have been

registered in some states for ground squirrel control

and have been found to be quite effective. Both are

formulated under a number of trade names. Death will

occur within 4 to 9 days if a continual supply of the

bait is consumed. If baiting is interrupted or a

sufficient amount is not maintained during the control

period, the toxic effects of the chemicals wear off and

the animal will recover.

Baiting should not begin

until the entire population is active, 2 to 3 weeks

after the first adults appear. If a portion of the

population is in hibernation or estivation, only the

active animals will be affected.

Bait selection should be

based on the animal’s feeding habits, time of year, and

crop type. Ground squirrel feeding habits vary with the

time of year. Grain baits may be more acceptable during

the spring when the amount of green vegetation is

limited. Pelletized baits using alfalfa or grass as a

major constituent may be preferred later in the season.

It is important to test

the acceptance of a bait before a formal baiting program

begins. Place clean (untreated) grains by several active

burrows. Use only grains acceptable to the animals as a

bait carrier. If none of the grains are consumed, the

same procedure can be repeated for pelletized baits.

Several formulations may need to be tried before an

acceptable bait is selected.

If control with one bait

is unsuccessful, rebaiting with another toxicant may

produce the desired results. This is particularly

important when zinc phosphide is used. Follow-up

treatments with an anticoagulant will often control the

remaining animals.

Bait placement is

critical. Bait should be scattered adjacent to each

active burrow in the amount and manner specified on the

label. It should not be placed in the burrow, because it

will either be covered with soil or pushed out of the

hole by the squirrels. Ground squirrels are accustomed

to foraging above ground for their food and are

suspicious of anything placed in their tunnel systems.

All active burrows must be baited. Incomplete coverage

of the colony will result in poor control success.

Where broadcast

applications are not allowed, baits can be placed in

spill-proof containers. Old tires have been extensively

used in the past but are bulky, heavy, and

time-consuming to cut apart and move. Furthermore, bait

can easily be pushed out by the animals and the tires

can ruin a good sickle bar or header if not removed from

a field before harvest. Corrugated plastic drain pipe of

different diameters cut into 18- to 24-inch (46-to

61-cm) lengths provide an inexpensive, light-weight, and

easy-to-use alternative.

Bait stations should be

placed in the field at about 50-foot (15-m) intervals a

week or so before treatments are to begin. Once the

animals use the stations frequently, baiting can begin.

Not all bait stations will be used by the squirrels at

the same time or with the same frequency. Each station

should be checked every 24 hours and consumed or

contaminated baits replaced until feeding stops. When

the desired level of control has been achieved, the bait

stations should be removed from the field and the old

bait returned to the original container or properly

disposed.

Fumigants

Fumigants are best suited

to small acreages of light squirrel infestations.

Most are only effective in

tight, compact, moist soils over 60o F (15o C). The gas

dissipates too rapidly in loose dry soils to be

effective in any extensive burrow system. Ground

squirrel burrow systems are often complex with several

openings and numerous interconnecting tunnels. The cost

of using gas cartridges may be more than eight times the

cost of using toxic baits.

Fumigants registered for

ground squirrel control include aluminum phosphide and

gas cartridges. Cartridges may contain several

combustible ingredients.

When using aluminum

phosphide, place tablets at multiple entrances at the

same time. Insert the tablets as far back into the

burrows as possible. Water may be added to the soil to

improve activity. Never allow aluminum phosphide to come

into direct contact with water, because the two together

can be explosive. Crumpled paper should be placed in the

hole to prevent the fumigant from being pushed out of

the hole by the animals or being covered by loose soil.

Plug the burrow opening with soil to form an air-tight

seal. Monitor the area for escaping gas and plug holes

as needed.

When using gas cartridges,

punch five or six holes in one end of each gas cartridge

and loosen the contents for more complete combustion

before use. Insert and light a fuse. Gently slide the

cartridge, fuse end first, as far back into the burrow

opening as possible and immediately seal the hole with

soil. Do not cover or smother the cartridge. Follow all

label instructions.

Phosphine gas is toxic to

all forms of animal life. Inhalation can produce a

sensation of pressure in the chest, dizziness, nausea,

vomiting, and a rapid onset of stupor. Affected people

or animals should be exposed to fresh air and receive

immediate medical attention. Never carry a container of

aluminum phosphide in an enclosed vehicle.

Trapping

Traps are best suited for

removal of small populations of ground squirrels where

other control methods are unsatisfactory or undesirable.

Jaw traps (No. 1 or No. 0), box or cage traps, and

burrow entrance traps may be used.

Place leghold traps where

squirrels will travel over them when entering and

leaving their burrows. Conceal the trap by placing it in

a shallow excavation and covering it with 1/8 to 1/4

inch (0.3 to 0.6 cm) of soil. Be certain that there is

no soil beneath the trap pan to impede its action. No

bait is necessary.

Box or cage traps may be

set in any areas frequented by ground squirrels. Place

them solidly on the ground so that they will not tip or

rock when the squirrel enters. Never place the trap

directly over a hole or on a mound. Cover the floor of

the trap with soil and bait it with fresh fruit,

vegetables, greens, peanut butter, or grain. Experiment

to find the best bait or combination of baits for your

area and time of year. Wire the door of the trap open

for 2 to 3 days and replenish the bait daily to help

overcome the squirrel’s trap shyness and increase

trapping success.

Shooting

Shooting may provide

relief from ground squirrel depredation where very small

colonies are under constant shooting pressure. It is,

however, an expensive and time-consuming practice.

Hunting licenses may be required in some states.

Other Methods

Gas exploding devices for

controlling burrowing rodents have not proven to be

effective. Propane/oxygen mixtures injected for 45

seconds and then ignited only reduced the population by

about 40%. Vacuum devices that suck rodents out of their

burrows are currently being developed and tested. No

reliable data, however, exist at this time to confirm or

deny their efficacy.

Economics of Damage and Control

Very little is known about

the economic consequences of ground squirrels foraging

in agriculture. A single pair and their offspring can

remove about 1/4 acre (0.1 ha) of wheat or alfalfa

during one season. Water lost from one canal can flood

thousands of acres or cause irrigation failures. The

crop loss and cost of repair can be very expensive.

Prevention, by incorporating a rodent management plan

into the total operation of an enterprise, far outweighs

the cost of added management practices.

Acknowledgments

Figure 1 from Schwartz and

Schwartz (1981).

Figures 2 and 3 adapted

from Burt and Grossenheider (1976) by David Thornhill.

Some of the material

included in this draft was written by C. Ray Record in

the 1983 edition of

Prevention and Control of

Wildlife Damage.

For Additional Information

Albert, S. W., and C.R. Record. 1982. Efficacy and cost

of four rodenticides for controlling Columbian ground

squirrel in western Montana. Great Plains Wildl. Damage

Control Workshop. 5:218-230.

Andelt, W. F., and T. M.

Race. 1991. Managing Wyoming (Richardson’s) ground

squirrels in Colorado. Coop. Ext. Bull. 6.505, Colorado

State Univ. 3 pp.

Askham, L. R. 1985.

Effectiveness of two anticoagulant rodenticides (chlorophacinone

and bromadiolone) for Columbian ground squirrel (Spermophilus

columbianus) control in eastern Washington. Crop

Protect. 4(3):365-371.

Askham, L. R. 1990. Effect

of artificial perches and nests in attracting raptors to

orchards. Proc. Vertebr. Pest. Conf. 14:144-148.

Askham, L. R., and R. M.

Poché. 1992. Biodeterioration of cholorphacinone in

voles, hawks and an owl. Mammallia 56(1):145-150.

Burt, W. H., and R. P.

Grossenheider. 1976. A field guide to the mammals, 3d

ed. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. 289 pp.

Edge, W. D., and S. L.

Olson-Edge. 1990. A comparison of three traps for

removal of Columbian ground squirrels. Proc. Vertebr.

Pest Conf. 14:104-106.

Fagerstone, K. A. 1988.

The annual cycle of Wyoming ground squirrels in

Colorado. J. Mamm. 69:678-687.

Lewis, S. R., and J. M.

O’Brien. 1990. Survey of rodent and rabbit damage to

alfalfa hay in Nevada. Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf.

14:116-119.

Matschke, G. H., and K. A.

Fagerstone. 1982. Population reduction of Richardson’s

ground squirrels with zinc phosphide. J. Wildl. Manage.

46:671-677.

Matschke, G. H., M. P.

Marsh, and D. L. Otis. 1983. Efficacy of zinc phosphide

broadcast baiting for controlling Richardson’s ground

squirrels on rangeland. J. Range. Manage. 36:504-506.

Pfeifer, S. 1980. Aerial

predation of Wyoming ground squirrels. J. Mamm.

61:371-372.

Schmutz, J. K., and D. J.

Hungle. 1989. Populations of ferruginous and Swainson’s

hawks increase in synchrony with ground squirrels. Can.

J. Zool. 67:2596-2601.

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri, rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp.

Sullins, M., and D.

Sullivan. 1992. Observations of a gas exploding device

for controlling burrowing rodents. Proc. Vertebr. Pest

Conf. 15:308-311.

Tomich, P. Q. 1992. Ground

squirrels. Pages 192-208 in J. A. Chapman and G. A.

Feldhamer. eds. Wild mammals of North America. The Johns

Hopkins Univ. Press., Baltimore, Maryland.

Wobeser, G. A., and F. A.

Weighton. 1979. A simple burrow entrance live trap for

ground squirrels. J. Wildl. Manage. 43:571-572.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

04/05/2006

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|