|

|

|

|

|

RODENTS: Squirrels, Belding's, California,

and Rock Ground |

|

|

Fig. 1.

Belding’s ground squirrel, Spermophilus beldingi (left)

Fig. 2. California ground squirrel, Spermophilus

beecheyi (right)

Introduction

Twenty-three species and

119 subspecies of ground squirrels exist in the United

States (Hall 1981). At least 10 species can be of

considerable economic importance to agriculture or have

a significant impact on public health. This chapter

covers the three species found in the far west and

southwest. All three species range over extensive

regions. While the California (Spermophilus beecheyi)

and the Belding’s (S. beldingi) ground squirrels are

considered pests over large agricultural areas, they are

not pests throughout their entire range. The rock ground

squirrel (S. variegatus) is not a major pest but is

important because of its involvement in the spread of

plague. The Belding ground squirrel (Fig. 1) is

medium-sized with a stocky build and short, furry (but

not bushy) tail. It is brownish gray to reddish brown in

color, and has no stripes, mottling, or markings of any

type. The underside of the body is dull cream-buff,

paling on the throat and inner sides of the legs.

Coloration varies somewhat with subspecies. The body is

about 8 1/2 inches (21.6 cm) long, with a 2 1/2-inch

(6.4-cm) tail. The ears are small and not prominent.

The California ground

squirrel (Fig. 2) is 10 inches (25.4 cm) long and

slightly larger than the Belding ground squirrel. It has

a moderately long (6 1/2-inch [16.5-cm]) semi-bushy

tail. Ears are tall and conspicuous, with some

exceptionally long hairs at the tips. The fur is

brownish gray and dusky, with a flecked or mottled and

grizzly appearance. Fur markings vary with subspecies.

The Douglas subspecies (S. b. douglasii), for example,

has a blackish brown wedge-shaped patch in the middle of

the back between the shoulders, which readily

distinguishes it from the other subspecies.

The rock ground squirrel

is a large-sized, heavy-bodied, ground squirrel (10 1/2

inches [26.7 cm] long) with a moderately long (8-inches

[20.3-cm]) bushy tail. Large prominent ears extend above

the top of the head. The fur is grayish, brownish gray,

or blackish and is mottled with light gray or whitish

specks or spots; coloration varies with subspecies. This

ground squirrel resembles the California ground squirrel

in many ways, but is somewhat larger and has a longer

and bushier tail. The ranges of the rock and the

California ground squirrels do not overlap; hence the

two squirrels cannot be confused with one another.

Range Range

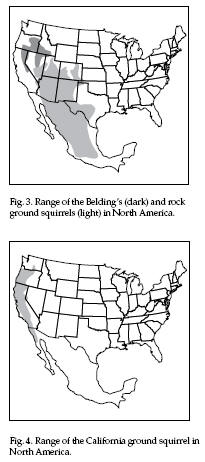

The Belding occupies the

northeastern part of California, extending northward

into eastern Oregon and eastward into the southwestern

portion of Idaho (Fig. 3). It also ranges into the

north-central portion of Nevada. It is the most numerous

and troublesome squirrel in Oregon and northeastern

California.

The California ground

squirrel’s range extends along the far west coast from

northern Mexico northward throughout much of California,

the western half of Oregon, and a moderate distance into

south-central Washington (Fig. 4). This species is

absent from the desert regions of California. It is the

most serious native rodent pest in California,

especially the subspecies (S. b. fisheri and S. b.

beecheyi,) which occupy the Central Valley and the

coastal region south from San Francisco.

The rock squirrel’s range

covers nearly all of Arizona and New Mexico. It extends

eastward into southwestern Texas and northward into

southern Nevada, and covers approximately two-thirds of

Utah and Colorado. More than half of its range extends

south into Mexico (Fig. 3).

Habitat

The large ranges of these

three species cut across highly varied habitat. The

habitat discussed here is more or less typical and the

one most often associated with economic losses.

Belding ground squirrels

live mainly in natural meadows and grasslands but are

adaptive to alfalfa, irrigated pastures, and the margins

of grain fields. At higher elevations they may occupy

meadows in forested areas, but they avoid forests or

dense brushlands.

California ground

squirrels occupy grasslands and savannah-like areas with

mixtures of oaks and grasslands. They avoid moderate to

heavily forested areas or dense brushlands. They

generally prefer open space, but they are highly

adaptable to disturbed environments and will infest

earthen dams, levees, irrigation ditch banks, railroad

rights-of-way, and road embankments, and will readily

burrow beneath buildings in rural areas. They thrive

along the margins of grain fields and other crops,

feeding out into the field.

Rock squirrels inhabit

rocky areas, hence their name. They live in rocky

canyons or on rocky hillsides in arid environments, but

they adapt to disturbed environments and will live along

stone walls and roadside irrigation ditches, feeding out

into cultivated fields.

Food Habits

Ground squirrels are

essentially herbivores, but insects sometimes make up a

very small portion of their diet. The California ground

squirrel, and possibly the other two, will consume eggs

of small ground-nesting birds, such as quail. Ground

squirrels are known to cannibalize their own kind and

sometimes scavenge on road kills of squirrels or other

vertebrate species. This, however, represents a very

small part of their overall diet.

All three species do well

in the absence of free water, even in the drier regions

of the west. They obtain needed water from dew or

succulent vegetation, plant bulbs, and bark. If water is

available, they will sometimes be seen drinking, but the

presence of a stream or stock reservoir does not offer

any special attraction for the squirrels.

Ground squirrels feed

almost exclusively on green vegetation when they emerge

from hibernation and throughout their gestation and

lactation period. As the grasses and herbaceous

vegetation begin to dry up in arid climates and to

produce seed, the squirrels switch to eating fruit or

seed for the majority of their diet. With the California

ground squirrel this switch is dramatic; a complete

change occurs over as short a period as 2 weeks. Using

their cheek pouches for carrying food items, the

California and rock ground squirrels are highly prone to

hoarding and caching food. The Belding is rarely seen in

this activity.

The Belding ground

squirrel feeds extensively on the leaves, stems, and

seeds of wild and cultivated grasses. Its diet, more

than that of the other species discussed in this

chapter, tends to change less dramatically and remains

heavily slanted toward green succulent vegetation rather

than seeds. This, in part, is because of a short active

period (from February to July) at higher elevations

where food is of high quality and plentiful, and few

seeds may have matured by the date the squirrels start

into hibernation. The lack of seeds in their diet

creates significant squirrel control problems because

commercial squirrel baits use cereal grains as the base

of their bait, hence the bait may be poorly accepted by

the squirrels. The Belding also consumes flowers, stems,

leaves, and roots of herbaceous plants, depending on its

habitat. It consumes seeds and fruit of mature plants in

greater quantities in regions where the hibernation

period is delayed until late summer or fall.

The California ground

squirrel feeds extensively on the leaves, stems, and

seeds of a wide variety of forage grasses and forbs,

depending on the availability in the area. In oak

savannah habitat, acorns are a favorite food. Thistle

seeds are also highly preferred. All grains and a wide

variety of other crops are consumed in cultivated areas

by this opportunistic feeder.

The food of the rock

squirrel is varied, depending on the native vegetation

of the region. It eats many kinds of grasses and forbs.

Acorns, pine nuts, juniper berries, mesquite buds and

beans, and fruit and seeds of various native plants,

including cactus, make up much of its diet.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

All species of ground

squirrels dig burrows for shelter and safety. The burrow

systems are occupied year after year and are extended in

length and complexity each year. Each system has

numerous entrances which are always left open and never

plugged with soil. The California and rock ground

squirrels are more colonial in their habits. A number of

squirrels occupy the same burrow system. The Belding

ground squirrel is somewhat less colonial and its

burrows are more widely dispersed.

Ground squirrels are rapid

runners and good climbers. Of the three species, the

California and rock ground squirrels are the most prone

to climbing. When scared by humans or predators, ground

squirrels always retreat to their burrows.

Ground squirrels are

hibernators. Most or all of the adult population goes

into hibernation during the coldest period of the year.

Squirrels born the previous spring may not go into

complete hibernation during the first winter. In hot

arid regions they may estivate, which is a temporary

summer sleep that may last for a few days to a couple of

weeks.

Male California and

Belding squirrels generally emerge from hibernation 10

to 14 days prior to the females. The reverse is reported

for rock squirrels. Breeding commences shortly after

emergence from hibernation. Breeding is fairly well

synchronized, with the vast majority of the females in

the area bred over about a 3-week period. Exact breeding

dates may vary from region to region depending on

weather, elevation, and latitude. Those farthest north

and at the higher elevations are latest to emerge from

hibernation and to breed. Gestation is 28 to 32 days,

and the young are born in a nest chamber in the burrow

system. The young are born hairless with their eyes

closed. They are nursed in the burrow until about 6 to 7

weeks of age (about one-third adult size), when they

begin to venture above ground and start feeding on green

vegetation. Only 1 litter is produced annually.

The litter size of the

California ground squirrel averages slightly over 7,

while that of the rock and Belding squirrels average 5

and 8, respectively. The rodent’s relatively slow annual

reproductive rate is compensated by a relatively long

life span of 4 to 5 years.

Damage and Damage Identification

Two of the three species

included in this chapter, the California and the

Belding, are considered serious agricultural pests where

they are found in moderate to high densities adjacent to

susceptible crops or home gardens. Rock squirrels

overall are relatively insignificant as agricultural

pests even though their damage may be economically

significant to individual growers. All three are

implicated in the transmission of certain diseases to

people, notably plague. This is the major reason that

rock squirrels are included in this chapter. They are

all adaptive and feed on a variety of crops, depending

on the ones grown in proximity to their natural habitat.

Since ground squirrels are active during daylight hours,

and their burrow openings are readily discernible,

damage identification is generally uncomplicated.

Their burrowing

activities, particularly those of the California and

Belding ground squirrels, weaken levees, ditch banks,

and earthen dams, and undermine roadways and buildings.

Burrows can also result in loss of irrigation water by

unwanted diversions, and in natural habitats they may

cause accelerated soil erosion by channeling rain or

snow runoff.

Burrow entrances in school

playgrounds, parks, and other recreational areas are

responsible for debilitating falls, occasionally

resulting in sprained or broken ankles or limbs. Burrows

in horse exercising or jumping arenas or on equestrian

trails can cause serious injuries to horses and to their

riders if thrown.

The Belding ground

squirrel, under favorable conditions, reaches incredible

densities, often exceeding 100 per acre (247/ha).

Extensive losses may be experienced in range forage,

irrigated pastures, alfalfa, wheat, oats, barley, and

rye.

The California ground

squirrel, where numerous, significantly depletes the

forage for livestock, reducing carrying capacity on

rangeland as well as irrigated pasture land. All grains,

and a wide variety of other crops, are consumed in

agricultural regions by this opportunistic feeder.

Almonds, pistachios, walnuts, apples, apricots, peaches,

prunes, oranges, tomatoes, and alfalfa are subject to

extensive damage. Certain vegetables and field crops

such as sugar beets, beans, and peas are taken at the

seedling stage, and orchard trees are sometimes injured

by bark gnawing.

Rock ground squirrels

consume peas, squash, corn, and grains of all kinds.

They also feed on various fruit, including apples,

cherries, apricots, peaches, pears, and melons,

primarily to obtain their seed. They sometimes dig up

and consume planted seed. Rock squirrels are not major

pests, however, because their preferred natural habitat

infrequently adjoins cultivated crops.

Legal Status

The three species of

ground squirrels discussed in this chapter are generally

regarded as pests and, as such, are not protected. Local

laws or regulations should, however, be consulted before

undertaking lethal control.

Be aware that several of

the numerous ground squirrel species are on the

threatened or endangered species lists. Any control of

pest species must take into consideration the

safeguarding and protection of endangered ground

squirrels and other rodent species.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Squirrels can be excluded from buildings with the

same techniques used to exclude commensal rats (see

Rodent-proof Construction and Exclusion Methods). Use

sheet metal cylinders around tree trunks to prevent loss

of fruit or nut crops.

While fences can be

constructed to exclude squirrels, they aren’t usually

practical because of their expense. Ground squirrels can

readily dig beneath fences that are buried several feet

(m) deep in the soil. Sheet metal caps atop a 4-foot

(1.2 m) wire mesh fence will prevent them from climbing

over. For a fence to remain squirrel-proof, the

squirrels that burrow near the fence should be

eliminated. Experiments with a temporary low electric

fence have been shown to seasonally discourage

California squirrels from invading research or small

garden plots from outside areas.

Cultural Methods and

Habitat Modification

Flood irrigation, as opposed to sprinkler or drip

irrigation, discourages ground squirrels in orchards,

alfalfa, and pasture land. It does not, however, get rid

of them completely. Ground squirrels are limited by

frequent tillage, especially deep discing or plowing.

Squirrels compensate by living at the margins of

cropland and then feeding inward from the field borders.

Keep fence lines vegetation-free by discing as close as

possible to them to limit the area where squirrels can

thrive.

Eliminate piles of orchard

prunings from the margins of the orchard to reduce cover

sought by the California ground squirrel. Remove

abandoned irrigation pipes or farm equipment from field

margins, as well as piles of rocks retrieved from

fields, to reduce sites beneath which the squirrels

prefer to burrow.

Frightening

Ground squirrels cannot be frightened from their

burrow sites by traditional frightening methods such as

propane exploders or flagging.

Repellents

Chemical taste and/or odor repellents are

ineffective in causing the squirrels to leave or avoid

an area or in preventing damage to growing crops. Seed

treatment repellents may offer some limited protection

to newly planted crops and may be state registered for

special local needs. Thiram is an example of a taste

repellent sometimes used as a seed protectant.

Toxicants

Rodenticide-treated baits are the most economical of all

approaches to population reduction and, hence, have

traditionally been the mainstay of ground squirrel

control. Currently, zinc phosphide is the only acute

rodenticide that is registered by EPA for the control of

Belding and California ground squirrels. In addition,

the anticoagulants diphacinone and chlorophacinone are

registered (some of these labels are state registrations

only). Cholecalciferol has a New Mexico state

registration for rock squirrels but not for any other

squirrel species. Zinc phosphide, for the most part, has

replaced 1080 and strychnine for squirrel control, since

the latter are no longer registered for these species.

Zinc phosphide is not

always highly efficacious, but efficacy is improved if

prebaiting is conducted. Bait shyness occurs when

sublethal doses are consumed at the initial feeding.

The chronic slower-acting

anticoagulants are more expensive to purchase and

require more bait because multiple feedings are

necessary to produce death. Also, death is delayed. On

the other hand, these accumulative poisons do not

produce bait shyness, thus providing more latitude than

zinc phosphide in the timing of baiting programs.

Zinc phosphide baits are

most often hand applied with a tablespoon (4 g) of bait

scattered on bare ground over about 3 or 4 square feet

(0.3 m2) next to the burrow entrance. Zinc phosphide is

a Restricted Use Pesticide when used in large

quantities; follow label instructions as to methods and

rates of application. Some labels permit broadcast

application of zinc phosphide and anticoagulant baits.

Use hand-cranked cyclone seeders or vehicle-mounted

tailgate seeders for such applications.

Anticoagulant

baits, depending on the label directions, may be hand

applied like zinc phosphide but require somewhat more

bait as well as repeated applications. Three or 4

applications a day on alternate days is a commonly used

schedule for the California ground squirrel. Double

strength diphacinone or chlorophacinone (0.01%) is most

effective for broadcast applications. Anticoagulant

baits, depending on the label directions, may be hand

applied like zinc phosphide but require somewhat more

bait as well as repeated applications. Three or 4

applications a day on alternate days is a commonly used

schedule for the California ground squirrel. Double

strength diphacinone or chlorophacinone (0.01%) is most

effective for broadcast applications.

Anticoagulant baits are

most often exposed in bait boxes, where a continuous

supply of bait will be available to the squirrels. Bait

boxes may be made of rubber tires, or metal, plastic, or

wood containers. Many are made of sections of 4-inch

(10-cm) plastic irrigation pipe designed in an inverted

“T” configuration (Fig. 5). Squirrels are often

reluctant to enter the bait boxes or stations for a few

days, and it may take several additional weeks before

all the squirrels are killed and bait consumption

ceases. Caching of bait does occur, especially with

California ground squirrels, and is more prevalent in

the late summer and fall of the year. Apply baits

earlier in the year to save bait.

The timing of baiting

programs is critical to good control. For maximum

effectiveness, bait only when all the squirrels are out

of hibernation or estivation and are actively feeding on

seed. Commercial baits are prepared on grain or

pelletized cereals.

To assure good bait

acceptance prior to an extensive control program,

acceptance should be tested by scattering tablespoons of

bait next to a few burrows. If all of the bait is gone

the next day, good bait acceptance is indicated. Bait

acceptance is especially important with zinc phosphide

or cholecalciferol, both of which require just a single

feeding to produce death. Good acceptance avoids poor

control and possible bait or toxin shyness, which will

adversely affect repeat control efforts.

If acceptance of cereal

baits is less than adequate (either prebait or test

baits are not consumed), then zinc phosphide application

should be delayed until bait acceptance is improved, or

not applied at all in favor of other control options.

Anticoagulant baits placed in bait stations can

sometimes be an effective option where zinc phosphide

acceptance is marginal. Squirrels may learn to take the

anticoagulant bait over time and, since they are

accumulatively poisoned with no bait shyness, control

will not be jeopardized by marginal feeding as long as

feeding continues over a number of days.

Fumigants

Ground squirrels can be killed in their burrow

systems by introducing one of several toxic or

suffocating gases, such as phosphine gas or carbon

monoxide. Fumigation should be conducted when the

squirrels are out of hibernation. Hibernating squirrels

plug their burrows with soil to separate themselves from

the outside, whereby they are safe from the lethal

consequences of the toxic gas.

Burrow fumigation has a

distinct advantage over toxicants and trapping in that

it is linked to no behavioral trait other than that

squirrels seek the cover of their burrows when

disturbed. Fumigation is most effective following ground

squirrel emergence from hibernation and before the

squirrels have time to reproduce. Recently born

squirrels, too young to venture above ground to be

baited or trapped, are effectively controlled by

fumigants.

Gas cartridges are easy to

use and are available from commercial manufacturers and

distributors or from the USDA supply depot at Pocatello,

Idaho. They consist of cylinders of combustible

ingredients with a fuse. Place the cartridge at the

entrance of the burrow and light the fuse; then, with a

shovel handle or stick, push the lit cartridge as far

back into the burrow as possible. Quickly cover the

burrow entrances with soil or sod and tamp tight to seal

in the toxic gases. The best results are obtained when

soil moisture is high, because less gas will escape the

system. Do not use near buildings, because high

temperatures may cause fires.

The method for using

aluminum phosphide differs considerably from that for

gas cartridges. Place the prescribed number of aluminum

phosphide tablets or pellets as far back into the burrow

opening as possible. Then insert a wad of crumpled

newspaper into the burrow and seal it tightly with soil.

The newspaper plug

prevents the soil from covering the pellets or tablets,

permitting them to react more readily with the

atmospheric and soil moisture to produce the lethal

phosphine gas. Aluminum phosphide is a Restricted Use

Pesticide. Knowledge of its proper handling is required.

Trapping

Although labor-intensive, trapping can be highly

effective in reducing low to moderate squirrel

populations over relatively small acreages or where

poison baits may be inappropriate. Trapping can be

conducted any time the squirrels are out of hibernation.

For humane reasons, avoid the period when the females

are lactating and nursing their young. Trapping prior to

the time the young are born is biologically most sound

from a control point of view.

An initial investment of

an adequate number of traps is required, but, if

properly maintained, traps will last many years. In

agricultural situations, 100 or more traps may be needed

to start with. A good rule of thumb is one trap for

every 10 to 15 squirrels present. If too few traps are

used, the trapper becomes discouraged long before the

squirrel population is brought under control. Several

types of traps are used for ground squirrels. A modified

pocket gopher kill-type box trap has been used to trap

the California ground squirrel for many years (Fig. 6).

It can be set near burrow openings, in trails, or in

trees where nut or fruit crops are being damaged. Bait

traps with walnuts, almonds, slices of orange, or pieces

of melon. With all types of squirrel traps, the control

period will be more decisive and maximum results

obtained if the traps are left unset or tied open and

baited for several days to permit the squirrels to get

used to them. Then rebait and set all the traps.

Unbaited Conibear® traps

(No. 110 or No. 110-2) with a 4 1/2 x 4 1/2-inch (11.4 x

11.4-cm) jaw spread are effective when set over the

burrow entrances. This method is not useful where

squirrels are living in the rocks or in rocky situations

where burrow entrances are inaccessible. A special trap

box (Fig. 7) will facilitate the use of Conibear® traps

that cannot be set over burrow openings. These make the

Conibear® traps more versatile as they can be set in

trails or near burrow openings. Conibears in trap boxes

must be baited to entice the squirrels into the trap. If

the squirrels are readily eating seed, then wheat, oats,

or barley can be used as bait. The Conibear® trap has

virtually replaced all uses of leghold traps in the far

west for ground squirrel control.

Live-catch wire or wooden

traps can be used to trap ground squirrels in

residential areas where kill-type traps are considered

inappropriate from a public relations point of view. The

captured squirrels should be removed from the site and

humanely euthanized with carbon dioxide. Releasing live

ground squirrels elsewhere is illegal in some states,

uneconomical, and rarely biologically sound in any

holistic approach to pest management or disease

prevention.

Shooting

If local laws permit, shooting with a .22 rifle may

provide some control where squirrel numbers are low, but

it is very time-consuming. For safety considerations,

shooting is generally limited to rural situations and is

considered too hazardous in many more populated areas,

even if legal. Ground squirrels that are repeatedly shot

at become very hunter/gun-shy. Rarely can one get close

enough to use a pellet gun effectively, and the noise of

a shotgun scares the squirrels sufficiently that after

the first shot, the remaining squirrels will be very

hesitant to emerge from their burrows.

Other Methods

Once ground squirrels have

been removed from a crop area, their reinvasion can be

substantially slowed by ripping up their old burrow

sites to a depth of at least 20 inches (51 cm),

preferably deeper. One to three ripping tongs mounted on

the hydraulic implement bar of a tractor works well.

Spacing between rips should be about 3 feet (1 m). This

approach is not suitable where the burrows are beneath

large rocks or trees.

Economics of Damage and Control

In one experimental study,

12 California ground squirrels were found to consume

about 1,000 pounds (454 kg) of range forage. In another

study, it was calculated that 200 ground squirrels

consumed the same amount as a 1,000-pound (454-kg)

steer. In spite of control, the California ground

squirrel has caused an estimated 30 to 50 million

dollars of agricultural and other damage annually in

California alone.

A northern California

study of the Belding’s ground squirrel showed that 123

squirrels per acre (304/ha) destroyed 1,790 pounds of

alfalfa per acre (2,006 kg/ha) over one growing season.

Little seems to be

recorded concerning the extent or amount of economic

damage caused by the rock squirrel. Economic loss is

believed to be relatively low, but the rock squirrel’s

role in the transmission of plague makes it important

from a public health viewpoint.

The cost of control varies

with the situation, squirrel density, and methods

employed. Baiting with an acute toxicant like zinc

phosphide is the most economical method, with 1 pound

(454 g) of bait ample for placement adjacent to 60

burrow entrances. The use of anticoagulant baits is

considerably more expensive, requiring anywhere from 1/2

to 1 1/4 pounds (227 to 568 g) of bait per squirrel. The

expense of bait stations would be an added cost.

The use of burrow

fumigants is about 8 to 10 times more expensive for

materials and labor than the use of zinc phosphide

baits. Trapping is half again more expensive than burrow

fumigation.

Figure 5, 6, and 7 adapted

from R. E. Marsh by David Thornhill.

For

Additional Information

Beard, M. L., G. O.

Maupin, A. M. Barnes, and E. F. Marshall. 1987.

Laboratory trials of cholecalciferol against

Spermophilus variegatus (rock squirrels), a source of

human plague (Yersinia pestis) in the southwestern

United States. J. Environ. Health 50:287-289.

Clark, J. P. 1986.

Vertebrate pest control handbook (rev.). Div. Plant

Industry, California Dep. Food Agric., Sacramento,

California. 350 pp.

Hall, E. R. 1981. The

mammals of North America. Vol. 1, 2d ed. John Wiley and

Sons, New York. 600 pp.

Marsh, R. E. 1987. Ground

squirrel control strategies in California agriculture.

Pages 261-276 in C. G. J. Richards and T. Y. Ku, eds.

Control of mammal pests. Taylor & Francis, London.

Salmon, T. P. 1981.

Controlling ground squirrels around structures, gardens,

and small farms. Div. Agric. Sci., Univ. California,

Leaflet 21179. 11 pp.

Salmon, T. P., and R. H.

Schmidt. 1984. An introductory overview to California

ground squirrel control. Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf.

11:32-37.

Tomich, P. Q. 1982. Ground

squirrels. Pages 192208 in J. A. Chapman and G. A.

Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North America: biology,

management, and economics. The Johns Hopkins Univ.

Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom, Robert

M. Timm, Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|