|

|

|

|

|

RODENTS: Roof Rats |

|

|

Fig. 1. Roof rat, Rattus

rattus

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Many control methods are

essentially the same for roof rats as for Norway rats.

Identification

The roof rat (Rattus

rattus, Fig. 1) is one of two introduced rats found in

the contiguous 48 states. The Norway rat (R. norvegicus)

is the other species and is better known because of its

widespread distribution. A third rat species, the

Polynesian rat (R. exulans) is present in the Hawaiian

Islands but not on the mainland. Rattus rattus is

commonly known as the roof rat, black rat, and ship rat.

Roof rats were common on early sailing ships and

apparently arrived in North America by that route. This

rat has a long history as a carrier of plague.

Three subspecies have been

named, and these are generally identified by their fur

color: (1) the black rat (R. rattus rattus Linnaeus) is

black with a gray belly; (2) the Alexandrine rat (R.

rattus alexandrinus Geoffroy) has an agouti (brownish

streaked with gray) back and gray belly; and (3) the

fruit rat (R. rattus frugivorus Rafinesque), has an

agouti back and white belly. The reliability of using

coloration to identify the subspecies is questionable,

and little significance can be attributed to subspecies

differentiations. In some areas the subspecies are not

distinct because more than one subspecies has probably

been introduced and crossbreeding among them is a common

occurrence. Roof rats cannot, however, cross with Norway

rats or any native rodent species.

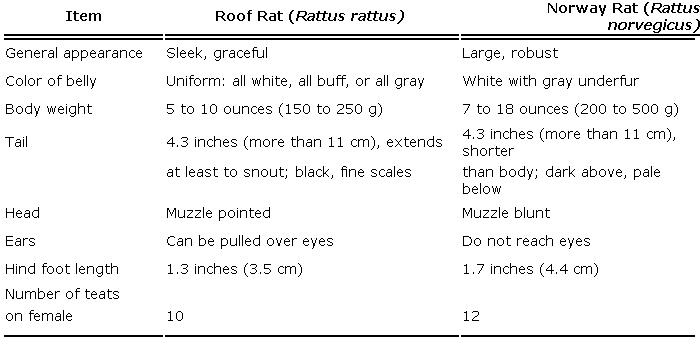

Some of the key

differences between roof and Norway rats are given in

Table 1. An illustration of differences is provided in

figure 2 of the chapter on Norway rats.

Table 1. Identifying

characteristics of adult rats.

Range Range

Roof rats range along the

lower half of the East Coast and throughout the Gulf

States upward into Arkansas. They also exist all along

the Pacific Coast and are found on the Hawaiian Islands

(Fig. 2). The roof rat is more at home in warm climates,

and apparently less adaptable, than the Norway rat,

which is why it has not spread throughout the country.

Its worldwide geographic distribution suggests that it

is much more suited to tropical and semitropical

climates. In rare instances, isolated populations are

found in areas not within their normal distribution

range in the United States. Most of the states in the US

interior are free of roof rats, but isolated

infestations, probably stemming from infested cargo

shipments, can occur.

Habitat

Roof rats are more aerial than Norway rats in their

habitat selection and often live in trees or on

vine-covered fences. Landscaped residential or

industrial areas provide good habitat, as does riparian

vegetation of riverbanks and streams. Parks with natural

and artificial ponds, or reservoirs may also be

infested. Roof rats will often move into sugarcane and

citrus groves. They are sometimes found living in rice

fields or around poultry or other farm buildings as well

as in industrial sites where food and shelter are

available.

Roof rats frequently enter

buildings from the roof or from accesses near overhead

utility lines, which they use to travel from area to

area. They are often found living on the second floor of

a warehouse in which Norway rats occupy the first or

basement floor. Once established, they readily breed and

thrive within buildings, just as Norway rats do. They

have also been found living in sewer systems, but this

is not common.

Food

Habits

The food habits of roof

rats outdoors in some respects resemble those of tree

squirrels, since they prefer a wide variety of fruit and

nuts. They also feed on a variety of vegetative parts of

ornamental and native plant materials. Like Norway rats,

they are omnivorous and, if necessary, will feed on

almost anything. In food-processing and storage

facilities, they will feed on nearly all food items,

though their food preferences may differ from those of

Norway rats. They do very well on feed provided for

domestic animals such as swine, dairy cows, and

chickens, as well as on dog and cat food. There is often

a correlation between rat problems and the keeping of

dogs, especially where dogs are fed outdoors. Roof rats

usually require water daily, though their local diet may

provide an adequate amount if it is high in water

content.

General Biology

Control methods must

reflect an understanding of the roof rat’s habitat

requirements, reproductive capabilities, food habits,

life history, behavior, senses, movements, and the

dynamics of its population structure. Without this

knowledge, both time and money are wasted, and the

chances of failure are increased.

Unfortunately, the rat’s

great adaptability to varying environmental conditions

can sometimes make this information elusive.

Reproduction and

Development

The young are born in a

nest about 21 to 23 days after conception. At birth they

are hairless, and their eyes are closed. The 5 to 8

young in the litter develop rapidly, growing hair within

a week. Between 9 and 14 days, their eyes open, and they

begin to explore for food and move about near their

nest. In the third week they begin to take solid food.

The number of litters depends on the area and varies

with nearness to the limit of their climatic range,

availability of nutritious food, density of the local

rat population, and the age of the rat. Typically, 3 or

more litters are produced annually.

The young may continue to

nurse until 4 or 5 weeks old. By this time they have

learned what is good to eat by experimenting with

potential food items and by imitating their mother.

Young rats generally

cannot be trapped until about 1 month old. At about 3

months of age they are completely independent of the

mother and are reproductively mature.

Breeding seasons vary in

different areas. In tropical or semitropical regions,

the season may be nearly year-round. Usually the peaks

in breeding occur in the spring and fall. Roof rats

prefer to nest in locations off of the ground and rarely

dig burrows for living quarters if off-the-ground sites

exist.

Feeding Behavior

Rats usually begin

searching for food shortly after sunset. If the food is

in an exposed area and too large to be eaten quickly,

but not too large to be moved, they will usually carry

it to a hiding place before eating it. Many rats may

cache or hoard considerable amounts of solid food, which

they eat later. Such caches may be found in a dismantled

wood pile, attic, or behind boxes in a garage.

When necessary, roof rats

will travel considerable distances (100 to 300 feet [30

to 90 m]) for food. They may live in the landscaping of

one residence and feed at another. They can often be

seen at night running along overhead utility lines or

fences. They may live in trees, such as palm, or in

attics, and climb down to a food source. Traditional

baiting or trapping on the ground or floor may intercept

very few roof rats unless bait and/or traps are placed

at the very points that rats traverse from above to a

food resource. Roof rats have a strong tendency to avoid

new objects in their environment and this neophobia can

influence control efforts, for it may take several days

before they will approach a bait station or trap.

Neophobia is more pronounced in roof rats than in Norway

rats. Some roof rat populations are skittish and will

modify their travel routes and feeding locations if

severely and frequently disturbed. Disturbances such as

habitat modifications should be avoided until the

population is under control.

Senses

Rats rely more on their

keen senses of smell, taste, touch, and hearing than on

vision. They are considered to be color-blind,

responding only to the degree of lightness and darkness

of color.

They use their keen sense

of smell to locate and select food items, identify

territories and travel routes, and recognize other rats,

especially those of the opposite sex. Taste perception

of rats is good; once rats locate food, the taste will

determine their food preferences.

Touch is an important

sense in rats. The long, sensitive whiskers (vibrissae)

near their nose and the guard hairs on their body are

used as tactile sensors. The whiskers and guard hairs

enable the animals to travel adjacent to walls in the

dark and in burrows.

Roof rats also have an

excellent sense of balance. They use their tails for

balance while traveling along overhead utility lines.

They move faster than Norway rats and are very agile

climbers, which enables them to quickly escape

predators. Their keen sense of hearing also aids in

their ability to detect and escape danger.

Social Behavior

The social behavior of

free-living roof rats is very difficult to study and, as

a result, has received less attention than that of

Norway rats. Most information on this subject comes from

populations confined in cages or outdoor pens.

Rats tend to segregate

themselves socially in both space and time. The more

dominant individuals occupy the better habitats and feed

whenever they like, whereas the less fortunate

individuals may have to occupy marginal habitat and feed

when the more dominant rats are not present.

Knowledge is limited on

interspecific competition between the different genera

and species of rats. At least in some parts of the

United States and elsewhere in the world, the methods

used to control rats have reduced Norway rat populations

but have permitted roof rats to become more prominent,

apparently because they are more difficult to control.

Elsewhere, reports indicate that roof rats are slowly

disappearing from localized areas for no apparent

reason.

It has often been said

that Norway rats will displace roof rats whenever they

come together, but the evidence is not altogether

convincing.

Population Dynamics

Rat densities (numbers of

rats in a given area) are determined primarily by the

suitability of the habitat—the amount of available

nutritional and palatable food and nearby protective

cover (shelter or harborage).

The great adaptability of

rats to human-created environments and the high

fertility rate of rats make for quick recuperation of

their populations. A control operation, therefore, must

reduce numbers to a very low level; otherwise, rats will

not only reproduce rapidly, but often quickly exceed

their former density for a short period of time.

Unless the suitability of

the rat’s habitat is destroyed by modifying the

landscaping, improving sanitation, and rat-proofing,

control methods must be unrelenting if they are to be

effective.

Damage

and Damage Identification

Nature of Damage

In food-processing and

food-storage facilities, roof rats do about the same

type of damage as Norway rats, and damage is visually

hard to differentiate. In residences where rats may be

living in the attic and feeding outdoors, the damage may

be restricted to tearing up insulation for nesting or

gnawing electrical wiring. Sometimes rats get into the

kitchen area and feed on stored foods. If living under a

refrigerator or freezer, they may disable the unit by

gnawing the electrical wires. In landscaped yards they

often live in overgrown shrubbery or vines, feeding on

ornamentals, vegetables, fruits, and nuts. Snails are a

favorite food, but don’t expect roof rats to eliminate a

garden snail problem. In some situations, pet food and

poorly managed garbage may represent a major food

resource.

In some agricultural

areas, roof rats cause significant losses of tree crops

such as citrus and avocados and, to a lesser extent,

walnuts, almonds, and other nuts. They often eat all the

pulp from oranges while the fruit is still hanging on

the tree, leaving only the empty rind. With lemons they

may eat only the rind and leave the hanging fruit

intact. They may eat the bark of smaller citrus branches

and girdle them. In sugarcane, they move into the field

as the cane matures and feed on the cane stalks. While

they may not kill the stalk outright, secondary

organisms generally invade and reduce the sugar quality.

Norway rats are a common mammalian pest of rice, but

sometimes roof rats also feed on newly planted seed or

the seedling as it emerges. Other vegetable, melon,

berry, and fruit crops occasionally suffer relatively

minor damage when adjacent to infested habitat such as

riparian vegetation.

Like the Norway rat, the

roof rat is implicated in the transmission of a number

of diseases to humans, including murine typhus,

leptospirosis, salmonellosis (food poisoning), rat-bite

fever, and plague. It is also capable of transmitting a

number of diseases to domestic animals and is suspected

in the transference of ectoparasites from one place to

another.

Rat Sign

The nature of damage to

outdoor vegetation can often provide clues as to whether

it is caused by the roof or Norway rat. Other rat signs

may also assist, but be aware that both species may be

present. Setting a trap to collect a few specimens may

be the only sure way to identify the rat or rats

involved. Out-of-doors, roof rats may be present in low

to moderate numbers with little sign in the way of

tracks or droppings or runs and burrows.

There is less tendency to

see droppings, urine, or tracks on the floor in

buildings because rats may live overhead between floors,

above false ceilings, or in utility spaces, and venture

down to feed or obtain food. In food-storage facilities,

the most prominent sign may be smudge marks, the result

of oil and dirt rubbing off of their fur as they travel

along their aerial routes.

The adequate inspection of

a large facility for the presence and location of roof

rats often requires a nighttime search when the facility

is normally shut down. Use a powerful flashlight to spot

rats and to determine travel routes for the best

locations to set baits and traps. Sounds in the attic

are often the first indication of the presence of roof

rats in a residence. When everyone is asleep and the

house is quiet, the rats can be heard scurrying about.

Legal

Status

Roof rats are not

protected by law and can be controlled any time with

mechanical or chemical methods. Pesticides must be

registered for rat control by federal and/or state

authorities and used in accordance with label

directions.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

The damage control methods

used for roof rats are essentially the same as for

Norway rats. However, a few differences must be taken

into account.

Exclusion or

Rodent-proofing

When rodent-proofing

against roof rats, pay close attention to the roof and

roof line areas to assure all accesses are closed. Plug

or seal all openings of greater than 1/2 inch (1.3 cm)

diameter with concrete mortar, steel wool, or metal

flashing. Rodent-proofing against roof rats usually

requires more time to find entry points than for Norway

rats because of their greater climbing ability.

Eliminate vines growing on buildings and, when feasible,

overhanging tree limbs that may be used as travel

routes.

Attach rat guards to

overhead utility wires and maintain them regularly. Rat

guards are not without problems, however, because they

may fray the insulation and cause short circuits.

Habitat Modification

and Sanitation

The elimination of food

and water through good warehouse sanitation can do much

to reduce rodent infestation. Store pet food in sealed

containers and do not leave it out at night. Use proper

garbage and refuse disposal containers and implement

exterior sanitation programs. Emphasis should be placed

on the removal of as much harborage as is practical. For

further information see Norway Rats.

Dense shrubbery,

vine-covered trees and fences, and vine ground cover

make ideal harborage for roof rats. Severe pruning

and/or removal of certain ornamentals are often required

to obtain a degree of lasting rat control. Remove

preharvest fruits or nuts that drop in backyards. Strip

and destroy all unwanted fruit when the harvest period

is over.

In tree crops, some

cultural practices can be helpful. When practical,

remove extraneous vegetation adjacent to the crop that

may provide shelter for rats. Citrus trees, having very

low hanging skirts, are more prone to damage because

they provide rats with protection. Prune to raise the

skirts and remove any nests constructed in the trees. A

vegetation-free margin around the grove will slow rat

invasions because rats are more susceptible to predation

when crossing unfamiliar open areas.

Frightening

Rats have acute hearing

and can readily detect noises. They may be frightened by

sound-producing devices for awhile but they become

accustomed to constant and frequently repeated sounds

quickly. High-frequency sound-producing devices are

advertised for frightening rats, but almost no research

exists on their effects specifically on roof rats. It is

unlikely, however, they will be any more effective for

roof rats than for Norway rats. These devices must be

viewed with considerable skepticism, because research

has not proven them effective.

Lights (flashing or

continuously on) may repel rats at first, but rats will

quickly acclimate to them.

Repellents

Products sold as general

animal repellents, based on taste and/or odor, are

sometimes advertised to repel animals, including rats,

from garbage bags. The efficacy of such products for

rats is generally lacking. No chemical repellents are

specifically registered for rat control.

Toxicants

Rodenticides were once

categorized as acute (single-dose) or chronic (multipledose)

toxicants. However, the complexity in mode of action of

newer materials makes these classifications outdated. A

preferred categorization would be “anticoagulants” and

“non-anticoagulants” or “other rodenticides.”

Anticoagulants

(slow-acting, chronic toxicants). Roof rats are

susceptible to all of the various anticoagulant

rodenticides, but less so than Norway rats. Generally, a

few more feedings are necessary to produce death with

the first-generation anticoagulants (warfarin, pindone,

diphacinone, and chlorophacinone) but this is less

significant with the second-generation anticoagulants (bromadiolone

and brodifacoum). All anticoagulants provide excellent

roof rat control when prepared in acceptable baits. A

new second-generation anticoagulant, difethialone, is

presently being developed and EPA registration is

anticipated in the near future.

A few instances of

first-generation anticoagulant resistance have been

reported in roof rats; although not common, it may be

underestimated because so few resistance studies have

been conducted on this species. Resistance is of little

consequence in the control of roof rats, especially with

the newer rodenticides presently available. Where

anticoagulant resistance is known or suspected, the use

of first-generation anticoagulants should be avoided in

favor of the second-generation anticoagulants or one of

the nonanticoagulant rodenticides like bromethalin or

cholecalciferol.

Other rodenticides.

The older rodenticides, formerly referred to as acute

toxicants, such as arsenic, phosphorus, red squill, and

ANTU, are either no longer registered or of little

importance in rat control. The latter two were

ineffective for roof rats. Newer rodenticides are much

more efficacious and have resulted in the phasing out of

these older materials over the last 20 years.

At present there are three

rodenticides—zinc phosphide, cholecalciferol (vitamin

D3), and bromethalin—registered and available for roof

rat control. Since none of these are anticoagulants, all

can be used to control anticoagulant resistant

populations of roof rats.

Roof rats can be

controlled with the same baits used for Norway rats.

Most commercial baits are registered for both species of

rats and for house mice, but often they are less

acceptable to roof rats than to the other species. For

best results, try several baits to find out which one

rats consume most. No rat bait ingredient is universally

highly acceptable, and regional differences are the rule

rather than the exception.

Pelleted or loose cereal

anticoagulant baits are used extensively in

tamper-resistant bait boxes or stations for a permanent

baiting program for Norway rats and house mice. They may

not be effective on roof rats, however, because of their

usual placement. Bait stations are sometimes difficult

to place for roof rat control because of the rodents’

overhead traveling characteristics. Anticoagulant

paraffin-type bait blocks provide an alternative to bait

stations containing pelleted or loose cereal bait. Bait

blocks are easy to place in small areas and

difficult-to-reach locations out of the way of children,

pets, and nontarget species. Where label instructions

permit, small blocks can be placed or fastened on

rafters, ledges, or even attached to tree limbs, where

they are readily accessible to the arboreal rats.

Some of the

first-generation anticoagulants (pindone and warfarin)

are available as soluble rodenticides from which water

baits can be prepared. Liquid baits may be an effective

alternative in situations where normal baits are not

readily accepted, especially where water is scarce or

where rats must travel some distance to reach water.

In controlling roof rats

with rodenticides, a sharp distinction must be made

between control in and around buildings and control away

from buildings such as in landfills and dumps, along

drainage ditches and streams, in sewer water evaporation

ponds, and in parks. Control of roof rat damage in

agriculture represents yet another scenario.

Distinctions must be made as to which rodenticide

(registered product) to use, the method of application

or placement, and the amount of bait to apply. For

example, only zinc phosphide can be applied on the

ground to control rats in sugarcane or macadamia

orchards, and the sec-ond-generation anticoagulants,

cholecalciferol and bromethalin, can be used only in and

around buildings, not around crops or away from

buildings even in noncrop situations. Selection of

rodenticides and bait products must be done according to

label instructions. Labels will specify where and under

what conditions the bait can be used. Specifications may

vary depending on bait manufacturer even though the

active ingredient may be the same. The product label is

the law and dictates the product’s location of use and

use patterns.

Tracking powders.

Tracking powders play an important role in structural

rodent control. They are particularly useful for house

mouse control in situations where other methods seem

less appropriate. Certain first-generation

anticoagulants are registered as tracking powders for

roof rat control; however, none of the second generation

materials are so registered. Their use for roof rats is

limited to control within structures because roof rats

rarely produce burrows.

Tracking powders are used

much less often for roof rats than for Norway rats

because roof rats frequent overhead areas within

buildings. It is difficult to find suitable places to

lay the tracking powder that will not create a potential

problem of contaminating food or materials below the

placement sites.

Tracking powders can be

placed in voids behind walls, near points of entry, and

in well-defined trails. Tunnel boxes or bait boxes

specially designed to expose a layer of toxic powder

will reduce potential contamination problems and may

actually increase effectiveness. Some type of clean food

can be used to entice the rats to the boxes, or the

tracking powders can be used in conjunction with an

anticoagulant bait, with both placed in the same

station.

Fumigants

Since roof rats rarely dig

burrows, burrow fumigants are of limited use; however,

if they have constructed burrows, then fumigants that

are effective on Norway rats, such as aluminum phosphide

and gas cartridges, will be effective on roof rats.

Where an entire warehouse may be fumigated for insect

control with a material such as methyl bromide, all rats

and mice that are present will be killed. The fumigation

of structures, truck trailers, or rail cars should only

be done by a licensed pest control operator who is

trained in fumigation techniques. Rodent-infested

pallets of goods can be tarped and fumigated on an

individual or collective basis.

Trapping

Trapping is an effective

alternative to pesticides and recommended in some

situations. It is recommended for use in homes because,

unlike with poison baits, there is no risk of a rat

dying in an inaccessible place and creating an odor

problem.

The

common wooden snap traps that are effective for Norway

rats are effective for roof rats. Raisins, prunes,

peanut butter, nutmeats, and gumdrops make good baits

and are often better than meat or cat food baits. The

commercially available, expanded plastic treadle traps,

such as the Victor Professional Rat Trap, are

particularly effective if properly located in

well-traveled paths. They need not be baited. Place

traps where they will intercept rats on their way to

food, such as on overhead beams, pipes, ledges, or sills

frequently used as travel routes (Fig. 3). Some traps

should be placed on the floor, but more should be placed

above floor level (for example, on top of stacked

commodities). In homes, the attic and garage rafters

close to the infestation are the best trapping sites. The

common wooden snap traps that are effective for Norway

rats are effective for roof rats. Raisins, prunes,

peanut butter, nutmeats, and gumdrops make good baits

and are often better than meat or cat food baits. The

commercially available, expanded plastic treadle traps,

such as the Victor Professional Rat Trap, are

particularly effective if properly located in

well-traveled paths. They need not be baited. Place

traps where they will intercept rats on their way to

food, such as on overhead beams, pipes, ledges, or sills

frequently used as travel routes (Fig. 3). Some traps

should be placed on the floor, but more should be placed

above floor level (for example, on top of stacked

commodities). In homes, the attic and garage rafters

close to the infestation are the best trapping sites.

Pocket gopher box-type

traps (such as the DK-2 Gopher Getter) can be modified

to catch rats by reversing the action of the trigger.

Presently, only one such modified trap (Critter

Control’s Custom Squirrel & Rat Trap) is commercially

available. These kill traps are often baited with whole

nuts and are most useful in trapping rats in trees.

Their design makes them more rat-specific when used

out-of-doors than ordinary snap traps that sometimes

take birds. Caution should be taken to avoid trapping

nontarget species such as tree squirrels.

Wire-mesh, live traps

(Tomahawk®, Havahart®) are available for trapping rats.

Rats that are captured should be humanely destroyed and

not released elsewhere because of their role in disease

transmission, damage potential, and detrimental effect

on native wildlife.

Glue boards will catch

roof rats, but, like traps, they must be located on

beams, rafters, and along other travel routes, making

them more difficult to place effectively for roof rats

than for Norway rats or house mice. In general, glue

boards are more effective for house mice than for either

of the rat species.

Shooting

Where legal and not

hazardous, shooting of roof rats is effective at dusk as

they travel along utility lines. Air rifles, pellet

guns, and .22-caliber rifles loaded with bird shot are

most often used. Shooting is rarely effective by itself

and should be done in conjunction with trapping or

baiting programs.

Predators

In urban settings, cats

and owls prey on roof rats but have little if any effect

on well-established populations. In some situations in

which the rats have been eliminated, cats that are good

hunters may prevent reinfestation.

In agricultural settings,

weasels, foxes, coyotes, and other predators prey on

roof rats, but their take is inconsequential as a

population control factor. Because roof rats are fast

and agile, they are not easy prey for mammalian or avian

predators.

Economics of Damage and Control

Roof rats undoubtedly

cause millions of dollars a year in losses of food and

feed and from damaging structures and other gnawable

materials. On a nationwide basis, roof rats cause far

less economic loss than Norway rats because of their

limited distribution.

There are approximately

30,000 professional structural pest control operators in

the United States and about 70% of these are primarily

involved in general pest control, which includes rodent

control. It is difficult to estimate how much is spent

in structural pest control specifically for roof rats

because estimates generally group rodents together.

Sugarcane, citrus,

avocados, and macadamia nuts are the agricultural crops

that suffer the greatest losses. In Hawaii, annual

macadamia loss has recently been estimated at between $2

million and $4 million.

Acknowledgments

I wish to acknowledge my

colleague, Dr. Walter E. Howard, for information taken

from his publication The Rat: Its Biology and Control,

Division of Agricultural Sciences, University of

California, Leaflet 2896 (30 pp.), coauthored with R. E.

Marsh. I also wish to express my thanks to Dr. Robert

Timm, who authored the chapter on Norway rats. To avoid

duplication of information, this chapter relies on the

more detailed control methods presented in the chapter

Norway Rats.

Figure 1 from C. W.

Schwartz and E. R. Schwartz (1981). The Wild Mammals of

Missouri, rev. ed. Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356

pp.

Figures 2 and 3 from

Howard and Marsh (1980), adapted by David Thornhill.

For Additional Information

Dutson, V. J. 1974. The association of the roof rat (Rattus

rattus) with the Himalayan blackberry (Rubus discolor)

and Algerian ivy (Hedera canariensis) in California.

Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 6:41-48.

Frantz, S. C., and D. E.

Davis. 1991. Bionomics and integrated pest management of

commensal rodents. Pages 243-313 in J. R. Gorham, ed.

Ecology and management of food-industry pests. US Food

Drug Admin. Tech. Bull. Assoc. Official Analytical Chem.

Arlington, Virginia.

Howard, W. E., and R. E.

Marsh. 1980. The rat: its biology and control. Div.

Agric. Sci., Publ. 2896, Univ. California. 30 pp.

Jackson, W. B. 1990. Rats

and mice. Pages 9-85 in A. Mallis, ed. Handbook of pest

control. Franzak & Foster Co., Cleveland, Ohio.

Kaukeinen, D. E. 1984.

Resistance; what we need to know. Pest Manage.

3(3):26-30.

Khan, J. A. 1974.

Laboratory experiments on the food preferences of the

black rat (Rattus rattus L.). Zool. J. Linnean Soc.

54:167-184.

Lefebvre, L. W., R. M.

Engeman, D. G. Decker, and N. R. Holler. 1989.

Relationship of roof rat population indices with damage

to sugarcane. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 17:41-45.

Marsh, R. E., and R. O.

Baker. 1987. Roof rat control—a real challenge. Pest

Manage. 6(8):16-18,20,29.

Meehan, A. P. 1984. Rats

and mice: their biology and control. Rentokil Ltd. E.

Grinstead, United Kingdom. 383 pp.

Recht, M. A., R. Geck, G.

L. Challet, and J. P. Webb. 1988. The effect of habitat

management and toxic bait placement on the movement and

home range activities of telemetered Rattus rattus in

Orange County, California. Bull. Soc. Vector Ecol.

13:248-279.

Thompson, P. H. 1984.

Horsing around with roof rats in rural outbuildings.

Pest Control 52(8):36-38,40.

Tobin, M. E. 1992. Rodent

damage in Hawaiian macadamia orchards. Proc. Vertebr.

Pest Conf. 15:272-276.

Weber, W. J. 1982.

Diseases transmitted by rats and mice. Thomson Publ.,

Fresno, California. 182 pp.

Zdunowski, G. 1980.

Environmental manipulation in roof rat control programs.

Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 9:74-79.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom; Robert

M. Timm; Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

09/11/2006

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|