|

|

|

|

|

RODENTS: Prairie Dogs |

|

|

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

- Exclusion

Wire mesh fences can be installed but they are

usually not practical or cost-effective. Visual

barriers of suspended burlap, windrowed pine trees,

or snow fence may be effective.

- Cultural Methods

Modify grazing practices on mixed and mid-grass

rangelands to exclude or inhibit prairie dogs.

Cultivate, irrigate, and establish tall crops to

discourage prairie dog use.

- Frightening

No methods are effective.

- Repellents

None are registered

- Toxicants

Zinc phosphide.

- Fumigants

Aluminum phosphide. Gas cartridges.

- Trapping

Box traps. Snares. Conibear® No. 110 (body-gripping)

traps or equivalent.

- Shooting

Shooting with .22 rimfire or larger rifles.Day

shooting and spotlighting are effective where legal.

- Other Methods

Several home remedies have been used but most are

unsafe and are not cost-effective.

Identification

Prairie dogs (Fig. 1) are

stocky burrowing rodents that live in colonies called

“towns.” French explorers called them “little dogs”

because of the barking noise they make. Their legs are

short and muscular, adapted for digging. The tail and

other extremities are short. Their hair is rather coarse

with little underfur, and is sandy brown to cinnamon in

color with grizzled black and buff-colored tips. The

belly is light cream to white.

Five species of prairie

dogs are found in North America: the black-tailed (Cynomys

ludovicianus), Mexican (C. mexicanus), white-tailed (C.

leucurus), Gunnison’s (C. gunnisoni), and Utah prairie

dog (C. parvidens). The most abundant and widely

distributed of these is the black-tailed prairie dog,

which is named for its black-tipped tail. Adult

black-tailed prairie dogs weigh 2 to 3 pounds (0.9 to

1.4 kg) and are 14 to 17 inches (36 to 43 cm) long. The

Mexican prairie dog also has a black-tipped tail, but is

smaller than its northern relative. White-tailed, Gunni-son’s,

and Utah prairie dogs all have white-tipped tails.

White-tailed prairie dogs are usually smaller than

black-tailed prairie dogs, weighing between 1 1/2 and 2

1/2 pounds (0.7 to 1.1 kg). The Gunnison’s prairie dog

is the smallest of the five species.

Range Range

Prairie dogs occupied up

to 700 million acres of western grasslands in the early

1900s. The largest prairie dog colony on record, in

Texas, measured nearly 25,000 square miles (65,000 km2)

and contained an estimated 400 million prairie dogs.

Since 1900, prairie dog populations have been reduced by

as much as 98% in some areas and eliminated in others.

This reduction is largely the result of cultivation of

prairie soils and prairie dog control programs

implemented in the early and mid-1900s. Population

increases have been observed in the 1970s and 1980s,

possibly due to the increased restrictions on and

reduced use of toxicants.

Today, about 2 million

acres of prairie dog colonies remain in North America.

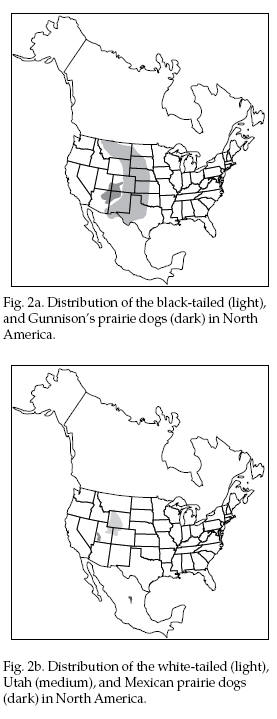

The black-tailed prairie

dog lives in densely populated colonies (20 to 35 per

acre [48 to 84/ha]) scattered across the Great Plains

from northern Mexico to southern Canada (Fig 2).

Occasionally they are found in the Rocky Mountain

foothills, but rarely at elevations over 8,000 feet

(2,438 m). The Mexican prairie dog occurs only in Mexico

and is an endangered species. White-tailed prairie dogs

live in sparsely populated colonies in arid regions up

to 10,000 feet (3,048 m). The Gunnison’s prairie dog

inhabits open grassy and brushy areas up to 12,000 feet

(3,658 m). Utah prairie dogs are a threatened species,

limited to central Utah.

Habitat

All species of prairie dogs are found in

grassland or short shrubland habitats. They prefer open

areas of low vegetation. They often establish colonies

near intermittent streams, water impoundments, homestead

sites, and windmills. They do not tolerate tall

vegetation well and avoid brush and timbered areas. In

tall, mid- and mixed-grass rangelands, prairie dogs have

a difficult time establishing a colony unless large

grazing animals (bison or livestock) have closely grazed

vegetation. Once established, prairie dogs can maintain

their habitat on mid-and mixed-grass rangelands. In

shortgrass prairies, where moisture is limited, prairie

dogs can invade and maintain acceptable habitat without

assistance.

Food

Habits

Prairie dogs are active

above ground only during the day and spend most of their

time foraging. In the spring and summer, individuals

consume up to 2 pounds (0.9 kg) of green grasses and

forbs (broad-leafed, nonwoody plants) per week. Grasses

are the preferred food, making up 62% to 95% of their

diet. Common foods include western wheatgrass, blue

grama, buffalo grass, sand dropseed, and sedges. Forbs

such as scarlet globe mallow, prickly pear, kochia,

peppergrass, and wooly plantain are common in prairie

dog diets and become more important in the fall, as

green grass becomes scarce. Prairie dogs also eat

flowers, seeds, shoots, roots, and insects when

available.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Prairie dogs are social

animals that live in towns of up to 1,000 acres (400 ha)

or more. Larger towns are often divided into wards by

barriers such as ridges, lines of trees, and roads.

Within a ward, each family or “coterie” of prairie dogs

occupies a territory of about 1 acre (0.4 ha). A coterie

usually consists of an adult male, one to four adult

females, and any of their offspring less than 2 years

old. Members of a coterie maintain unity through a

variety of calls, postures, displays, grooming, and

other forms of physical contact.

Black-tailed prairie dog

towns typically have 30 to 50 burrow entrances per acre,

while Gunnison’s and white-tailed prairie dog towns

contain less than 20 per acre. Most burrow entrances

lead to a tunnel that is 3 to 6 feet (1 to 2 m) deep and

about 15 feet (5 m) long. Prairie dogs construct crater-

and dome-shaped mounds up to 2 feet (0.6 m) high and 10

feet (3 m) in diameter. The mounds serve as lookout

stations. They also prevent water from entering the

tunnels and may enhance ventilation of the tunnels.

Prairie dogs are most

active during the day. In the summer, during the hottest

part of the day, they go below ground where it is much

cooler. Black-tailed prairie dogs are active all year,

but may stay underground for several days during severe

winter weather. The white-tailed, Gunnison’s, and Utah

prairie dogs hibernate from October through February.

Black-tailed prairie dogs

reach sexual maturity after their second winter and

breed only once per year. They can breed as early as

January and as late as March, depending on latitude. The

other four species of prairie dogs reach sexual maturity

after their first winter and breed in March. The

gestation period is about 34 days and litter sizes range

from 1 to 6 pups. The young are born hairless, blind,

and helpless. They remain underground for the first 6

weeks of their lives. The pups emerge from their dens

during May or June and are weaned shortly thereafter. By

the end of fall, they are nearly full grown. Survival of

prairie dog pups is high and adults may live from 5 to 8

years.

Even with their sentries

and underground lifestyle, predation is still a major

cause of mortality for prairie dogs. Badgers, weasels,

and black-footed ferrets are efficient predators.

Coyotes, bobcats, foxes, hawks, and eagles also kill

prairie dogs. Prairie rattlesnakes and bull snakes may

take young, but rarely take adult prairie dogs.

Accidents, starvation, weather, parasites, and diseases

also reduce prairie dog populations, but human

activities have had the greatest impact.

Prairie dog colonies

attract a wide variety of wildlife. One study identified

more than 140 species of wildlife associated with

prairie dog towns. Vacant prairie dog burrows serve as

homes for cottontail rabbits, small rodents, reptiles,

insects, and other arthropods. Many birds, such as

meadowlarks and grasshopper sparrows, appear in greater

numbers on prairie dog towns than in surrounding

prairie. The burrowing owl is one of several uncommon or

rare species that frequent prairie dog towns. Others

include the golden eagle, prairie falcon, ferruginous

hawk, mountain plover, swift fox, and endangered

black-footed ferret (see Appendix A of this chapter).

Damage

and Damage Identification

Several independent

studies have produced inconsistent results regarding the

impacts of prairie dogs on livestock production. The

impacts are difficult to determine and depend on several

factors, such as the site conditions, weather, current

and historic plant communities, number of prairie dogs,

size and age of prairie dog towns, and the intensity of

site use by livestock and other grazers. Prairie dogs

feed on many of the same grasses and forbs that

livestock feed on. Annual dietary overlap ranges from

64% to 90%. Prairie dogs often begin feeding on pastures

and rangeland earlier in spring than cattle do and clip

plants closer to the ground. Up to 10% of the

aboveground vegetation may be destroyed due to their

burrowing and mound-building activities. Overall,

prairie dogs may remove 18% to 90% of the available

forage through their activities.

The species composition of

pastures occupied by prairie dogs may change

dramatically. Prairie dog activities encourage

shortgrass species, perennials, forbs, and species that

are resistant to grazing. Annual plants are selected

against because they are usually clipped before they can

produce seed. Several of the succeeding plant species

are less palatable to livestock than the grasses they

replace.

Other studies, however,

indicate that prairie dogs may have little or no

significant effect on livestock production. One research

project in Oklahoma revealed that there were no

differences in annual weight gains between steers using

pastures inhabited by prairie dogs and steers in

pastures without prairie dogs. Reduced forage

availability in prairie dog towns may be partially

compensated for by the increased palatability and crude

protein of plants that are stimulated by grazing. In

addition, prairie dogs sometimes clip and/or eat plants

that are toxic to livestock. Bison, elk, and pronghorns

appear to prefer feeding in prairie dog colonies over

uncolonized grassland.

Prairie dog burrows

increase soil erosion and are a potential threat to

livestock, machinery, and horses with riders. Damage may

also occur to ditch banks, impoundments, field trails,

and roads.

Prairie dogs are

susceptible to several diseases, including plague, a

severe infectious disease caused by the bacterium

Yersinia pestis. Plague, which is often fatal to humans

and prairie dogs, is most often transmitted by the bite

of an infected flea. Although plague has been reported

throughout the western United States, it is uncommon.

Symptoms in humans include swollen and tender lymph

nodes, chills, and fever. The disease is curable if

diagnosed and treated in its early stages. It is

important that the public be aware of the disease and

avoid close contact with prairie dogs and other rodents.

Public health is a primary concern regarding prairie dog

colonies that are in close proximity to residential

areas and school yards.

Rattlesnakes and black

widow spiders also occur in prairie dog towns, but can

be avoided. Rattlesnakes often rest in prairie dog

burrows during the day and move through towns at night

in search of food. Black widow spiders are most often

found in abandoned prairie dog holes where they form

webs and raise their young. Bites from these animals are

rare, but are a threat to human health.

Legal Status

Black-tailed,

white-tailed, and Gunni-son’s prairie dogs are typically

classified as unprotected or nuisance animals, allowing

for their control without license or permit. Most states

require purchase of a small game license to shoot

prairie dogs. If the shooter is acting as an agent for

the landowner to reduce prairie dog numbers, a license

may not be required. The Utah and Mexican prairie dogs

are classified as threatened and endangered species,

respectively. Contact your local wildlife agency for

more information.

The black-footed ferret is

an endangered species that lives almost exclusively in

prairie dog towns, and all active prairie dog colonies

are potential black-footed ferret habitat. It is a

violation of federal law to willfully kill a

black-footed ferret or poison prairie dog towns where

ferrets are present. Federal agencies must assess their

own activities to determine if they “may affect”

endangered species. Some pesticides registered for

prairie dog control require private applicators to

conduct ferret surveys before toxicants can be applied.

Detailed information on identifying black-footed ferrets

and their sign is included in Appendix A of this

chapter. To learn more about federal and state

guidelines regarding prairie dog control, black-footed

ferret surveys, and block clearance procedures, contact

personnel from your local Cooperative Extension,

USDA-APHIS-ADC, US Fish and Wildlife Service, or state

wildlife agency office.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Fencing.

Exclusion of prairie dogs is rarely practical, although

they may be discouraged by tight-mesh, heavy-gauge,

galvanized wire, 5 feet (1.5 m) wide with 2 feet (60 cm)

buried in the ground and 3 feet (90 cm) remaining

aboveground. A slanting overhang at the top increases

the effectiveness of the fence.

Visual Barriers.

Prairie dogs graze and closely clip vegetation to

provide a clear view of their surroundings and improve

their ability to detect predators. Fences, hay bales,

and other objects can be used to block prairie dogs’

view and thus reduce suitability of the habitat.

Franklin and Garrett (1989) used a burlap fence to

reduce prairie dog activity over a two-month period.

Windrows of pine trees also reduced prairie dog

activity. Unfortunately, the utility of visual barriers

is limited because of high construction and maintenance

costs. Tensar snow fences (2 feet [60 cm] tall) are less

costly, at about $0.60 per foot ($1.97/m) for materials.

Unfortunately, they were inconsistent in reducing

reinvasion rates of prairie dog towns in Nebraska (Hygnstrom

and Virchow, unpub. data).

Cultural Methods

Grazing Management.

Proper range management can be used to control prairie

dogs. Use stocking rates that maintain sufficient stand

density and height to reduce recolonization of

previously controlled prairie dog towns or reduce

occupation of new areas. The following general

recommendations were developed with the assistance of

extension range management specialists and research

scientists.

Stocking Rate.

Overgrazed pastures are favorable for prairie dog town

establishment or expansion. If present, prairie dogs

should be included in stocking rate calculations. At a

conservative population density of 25 prairie dogs per

acre (60/ha) and dietary overlap of 75%, it takes 6

acres (2.4 ha) of prairie dogs to equal 1 Animal Unit

Month (AUM) (the amount of forage that one cow and calf

ingest per month during summer [about 900 pounds; 485

kg]).

Rest/Rotation

Grazing. Rest pastures for a period of time

during the growing season to increase grass height and

maintain desired grass species. Instead of season-long

continuous grazing, use short duration or rapid rotation

grazing systems, or even total deferment during the

growing season. Livestock can be excluded from vacant

prairie dog towns with temporary fencing to help

vegetation regain vigor and productivity. Mid- to

tallgrass species should be encouraged where they are a

part of the natural vegetation. In semiarid and

shortgrass prairie zones, grazing strategies may have

little effect on prairie dog town expansion or

establishment.

Grazing Distribution.

Prairie dogs often establish towns in areas where

livestock congregate, such as at watering sites or old

homesteads. Move watering facilities and place salt and

minerals on areas that are underutilized by livestock to

distribute livestock grazing pressure more evenly.

Prescribed burns in spring may enhance regrowth of

desirable grass species.

Cultivation.

Prairie dog numbers can be reduced by plowing or disking

towns and leaving the land fallow for 1 to 2 years,

where soil erosion is not a problem. Establish tall

grain crops after the second year to further discourage

prairie dogs. Burrows can be leveled and filled with a

tractor-mounted blade to help slow reinvasion. Flood

irrigation may discourage prairie dogs.

Frightening

Frightening is

not a practical means of control.

Repellents

None are

registered.

Toxicants

Safety Precautions. Use pesticides safely

and comply with all label recommendations. Only use

products that are registered for prairie dog control by

the Environmental Protection Agency. Some pesticides

registered for prairie dog control require that private

applicators conduct ferret surveys before toxicants can

be applied. Detailed information on identifying

black-footed ferrets and their sign is included in

Appendix A of this chapter. Seek assistance from your

local extension agent or from the USDA-APHIS-ADC if

needed.

Toxic Bait.

The only toxic baits currently registered and legal for

use to control prairie dogs are 2% zinc phosphide-treated

grain bait and pellet formulations. Zinc phosphide baits

are effective and relatively safe regarding livestock

and other wildlife in prairie dog towns, if used

properly. These baits are available through national

suppliers, USDA-APHIS-ADC, and local retail

distributors.

Toxic baits are most

effective when prairie dogs are active and when there is

no green forage available. Therefore, it is best to

apply baits in late summer and fall. Zinc phosphide

baits can only be applied from July 1 through January

31.

Prebaiting.

Prairie dog burrows must be prebaited before applying

toxic bait. Prebaiting will accustom prairie dogs to

eating grain and will make the toxic bait considerably

more effective when it is applied. Use clean rolled oats

as a prebait if you are using 2% zinc phosphide-treated

rolled oats. Drop a heaping teaspoon (4 g) of untreated

rolled oats on the bare soil at the edge of each prairie

dog mound or in an adjacent feeding area. The prebait

should scatter, forming about a 6-inch (15-cm) circle

(Fig. 3). Do not place the prebait in piles or inside

burrows, on top of mounds, among prairie dog droppings,

or in vegetation far from the mound.

Apply toxic bait only

after the prebait has been readily eaten, which usually

takes 1 to 2 days. If the prebait is not accepted

immediately, wait until it is eaten readily before

applying the toxic bait. More than one application of

prebait may be necessary if rain or snow falls on the

prebait. Prohibit shooting and other disturbance of the

colony at least 6 weeks prior to and during treatment.

Prebait and toxic bait can

be applied by hand on foot, but mechanical bait

dispensers attached to all-terrain vehicles are more

convenient and cost-ef-fective for towns greater than 20

acres (8 ha). Motorcycles and horses can also be used to

apply prebait and toxic bait.

Bait Application.

Apply about 1 heaping teaspoon (4 g) of grain bait per

burrow in the same way that the prebait was applied.

About 1/3 pound of prebait and 1/3 pound of zinc

phosphide bait are needed per acre (0.37 kg/ha). Excess

bait that is not eaten by prairie dogs can be a hazard

to nontarget wildlife or livestock. It is best to remove

livestock, especially horses, sheep, or goats, from the

pasture before toxic bait is applied; however, removal

is not required. Apply toxic bait early in the day for

best results and restrict any human disturbance for 3

days following treatment. Always wear rubber gloves when

handling zinc phosphide-treated baits. Follow all label

directions and observe warnings regarding bait storage

and handling.

Apply prebait and bait

during periods of settled weather, when vegetation is

dry and dormant. Avoid baiting on wet, cold, or windy

days. Bait acceptance is usually best after August 1st

or when prairie dogs are observed feeding on native

seeds and grains. Do not apply zinc phosphide to a

prairie dog town more than once per year. If desired,

survivors can be removed by fumigation or shooting.

Treatment with toxic baits, followed by a fumigant

cleanup, is most cost-effective for areas of more than 5

acres (2 ha).

Inspection and

evaluation. Inspect treated prairie dog towns 2

to 3 days after treatment. Remove and burn or bury any

dead prairie dogs that are aboveground to protect any

other animals from indirect poisoning. Success rates of

75% to 85% can usually be obtained with zinc phosphide

if it is applied correctly.

To evaluate the success of

a treatment, mark and plug 100 burrows 3 days prior to

treatment. Count the reopened burrows 24 hours later.

Replug the same 100 burrows 3 days after treatment and

again count the reopened burrows 24 hours later. Divide

the number of reopened burrows (posttreatment) by the

number of reopened burrows (pretreatment) to determine

the survival rate. Abandoned burrows are usually filled

with spider webs, vegetation, and debris. Active burrows

are clean and surrounded by tracks, diggings, and fresh

droppings at the entrances.

Zinc phosphide is a

Restricted Use Pesticide, available for sale to and use

by certified pesticide applicators or their designates.

Contact your county extension office for information on

acquiring EPA certification. Treatment of a prairie dog

town with zinc phosphide-treated baits cost about $10

per acre ($25/ha) (includes materials and labor).

Fumigants

Fumigants,

including aluminum phosphide tablets and gas cartridges,

can provide satisfactory control of prairie dogs in some

situations. We do not recommend fumigation as the

primary means of control for large numbers of prairie

dogs because it is costly, time-consuming, and usually

more hazardous to desirable wildlife species than toxic

baits. Fumigants cost about 5 to 10 times more per acre

(ha) to apply than toxic baits. Therefore, fumigation is

usually used during spring as a follow-up to toxic bait

treatment. Success rates of 85% to 95% can usually be

obtained if fumigants are applied correctly.

For best results, apply

fumigants in spring when soil moisture is high and soil

temperature is greater than 60o F (15o C). Fumigation

failures are most frequent in dry, porous soils. Spring

applications are better than fall applications because

all young prairie dogs are still in their natal burrows.

Do not use fumigants in

burrows where nontarget species are thought to be

present. Black-footed ferrets, burrowing owls, swift

fox, cottontail rabbits, and several other species of

wildlife occasionally inhabit prairie dog burrows and

would likely be killed by fumigation. Be aware of sign

and avoid fumigating burrows that are occupied by

nontarget wildlife. Some manufacturers’ labels now

require private applicators to conduct black-footed

ferret surveys before application. Detailed information

on identifying black-footed ferrets and their sign is

included in Appendix A of this chapter. Burrows used by

burrowing owls often have feathers, pellets, and

whitewash nearby. Natal burrows are often lined with

finely shredded cow manure. Migratory burrowing owls

usually arrive in the central Great Plains in late April

and leave in early October. Fumigate before late April

to minimize the threat to burrowing owls.

Aluminum Phosphide.

Aluminum phosphide is a Restricted Use Pesticide,

registered as a fumigant for the control of burrowing

rodents. The tablets react with moisture in prairie dog

burrows, and release toxic phosphine gas (PH3). Use a

4-foot (1.2-m) section of 2-inch (5-cm) PVC pipe to

improve placement of the tablets. Insert the pipe into a

burrow and roll the tablets down the pipe. Place

crumpled newspaper and/or a slice of sod in the burrow

to prevent loose soil from smothering the tablets and

tightly pack the burrow entrance with soil. To increase

efficiency, work in pairs, one person dispensing and one

plugging burrows.

Always wear cotton gloves

while handling aluminum phosphide. Aim containers away

from the face when opening and work into the wind to

avoid inhaling phosphine gas from the container and the

treated area. Aluminum phosphide should be stored in a

well-ventilated area, never inside a vehicle or occupied

building. Aluminum phosphide is classified as a

flammable solid. Check with your local department of

transportation for regulations regarding transportation

of hazardous materials.

Aluminum phosphide can be

purchased by certified pesticide applicators through

national suppliers (see Supplies and Materials) or local

retail distributors. It typically provides an 85% to 95%

reduction in prairie dog populations when applied

correctly and costs about $25 per acre ($63/ha) to

apply. It is typically more cost-effec-tive to use than

gas cartridges because of the reduced handling time.

Gas Cartridges.

Gas cartridges have been used for many years to control

prairie dogs. When ignited, they burn and produce carbon

monoxide, carbon dioxide, and other gases. To prepare a

gas cartridge for use, insert a nail or small

screwdriver in the end at marked points and stir the

contents before inserting and lighting the fuse. Hold

the cartridge away from you until it starts burning,

then place it deep in a burrow. Burrows should be

plugged immediately in the same way as with aluminum

phosphide. Be careful when using gas cartridges because

they can cause severe burns. Do not use them near

flammable materials or inside buildings. Gas cartridges

are a General Use Pesticide, available through

USDA-APHIS-ADC. They provide up to 95% control when

applied correctly and cost about $35 per acre ($88/ha)

to apply.

Trapping

Cage traps can

be used to capture individual animals, but the process

is typically too expensive and time consuming to be

employed for prairie dog control. Best results are

obtained by trapping in early spring after snowmelt and

before pasture green up. Bait traps with oats flavored

with corn oil or anise oil.

It may be difficult to

find release sites for prairie dogs. Releasing prairie

dogs into an established colony will increase stress on

resident and released prairie dogs.

Body-gripping traps, such

as the Conibear® No. 110, are effective when placed in

burrow entrances. No. 1 Gregerson snares can be used to

remove a few prairie dogs, but the snares are usually

rendered useless after each catch. Prairie dogs also can

be snared by hand, using twine or monofilament line.

These traps and snares may be effective for 1- to 5-acre

(0.4- to 2-ha) colonies where time is not a

consideration.

Shooting

Shooting is

very selective and not hazardous to nontarget wildlife.

It is most effective in spring because it can disrupt

prairie dog breeding. Continuous shooting can remove 65%

of the population during the year, but it usually is not

practical or cost-effective. Prairie dogs often become

wary and gun-shy after extended periods of shooting.

They can be conditioned to loud noises by installing a

propane cannon or old, mis-timed gasoline engine in the

town for 3 to 4 days before shooting.

Long range, flat

trajectory rifles are the most efficient for shooting

prairie dogs. Rifles of .22 caliber or slightly larger

are most commonly used. Bipods and portable shooting

benches, telescopic sights, and spotting scopes are also

useful equipment for efficient shooting. Contact a local

extension office or state wildlife agency for lists of

shooters and receptive landowners.

Other Methods

An amazing

variety of home remedies have been tried in desperate

attempts to control prairie dogs. Engine exhaust, dry

ice, butane, propane, gasoline, anhydrous ammonia,

insecticides, nonregistered rodenticides, water, and

dilute cement are all unregistered for prairie dog

control. None have proven to be as cost-effective or

successful as registered rodenticides, and most are

hazardous to applicators and/or nontarget species. In

addition, those methods that have been observed by the

authors (exhaust, propane, ammonia, nonregistered

rodenticides, and water) were substantially more

expensive than registered and recommended methods.

A modified street sweeper

vacuum has recently been used to suck prairie dogs out

of their burrows. Inventor Gay Balfour of Cortez,

Colorado, reports that the “Sucker Upper” can typically

clear a range of 5 to 20 acres (2 to 8 ha) per day at a

cost of $1,000 per day, not including travel expenses.

This device, unfortunately, has not been independently

tested. Although relatively expensive, this method may

provide a nonlethal approach to dealing with prairie

dogs where conventional methods are not appropriate or

acceptable. The prairie dogs can either be euthanized

with carbon dioxide gas or relocated if a suitable site

can be found.

Integrated Pest Management

An integrated

pest management approach dictates the timely use of a

variety of cost-effective management options to reduce

prairie dog damage to a tolerable level. We recommend

the application of toxic bait in the fall, followed by

the application of aluminum phosphide in the spring. If

possible, defer grazing on the treated area during the

next growing season to allow grasses and other

vegetation to recover. A computer program was produced

by Cox and Hygnstrom in 1993 to determine cost-effective

options and economic returns of prairie dog control (see

For Additional Information).

Economics of Damage and Control

Prairie dogs play an

important role in the prairie ecosystem by creating

islands of unique habitat that increase plant and animal

diversity. Prairie dogs are a source of food for several

predators and their burrows provide homes for several

species, including the endangered black-footed ferret.

Burrowing mixes soil types and incorporates organic

matter, both of which may benefit soil. It also

increases soil aeration and decreases compaction.

Prairie dogs provide recreational opportunities for

nature observers, photographers, and shooters. The

presence of large, healthy prairie dog towns, however,

is not always compatible with agriculture and other

human land-use interests.

Prairie dogs feed on many

of the same grasses and forbs that livestock do. Annual

dietary overlap has been estimated from 64% to 90%. One

cow and calf ingest about 900 pounds (485 kg) of forage

per month during the summer (1 AUM). One prairie dog

eats about 8 pounds (17.6 kg) of forage per month during

the summer. At a conservative population density of 25

prairie dogs per acre (60/ha) and dietary overlap of

75%, it takes 6 acres (2.4/ha) of prairie dogs to equal

1 AUM. Small, rather widely dispersed colonies occupying

20 acres (8 ha) or less are tolerated by many landowners

because of the sport hunting and aesthetic opportunities

they provide. Colonies that grow larger than 20 acres (8

ha) often exceed tolerance levels because of lost AUMs,

taxes, and increasing control costs.

The South Dakota

Department of Agriculture (1981) reported that 730,000

acres (292,000 ha) were inhabited by prairie dogs in

1980, with a loss of $9,570,000 in production. The South

Dakota livestock grazing industry similarly estimated

losses of up to $10.29 per acre ($25.43/ha) on pasture

and rangeland inhabited by prairie dogs and $30.00 per

acre ($74.10/ha) for occupied hay land. Prairie dogs

inhabited about 73,000 acres (29,200 ha) in Nebraska in

1987, with a loss estimated at $200,000. A reported 1/2

to 1 million acres (200,000 to 400,000 ha) are occupied

in Colorado. A committee of the National Academy of

Sciences (1970) concluded that “the numerous eradication

campaigns against prairie dogs and other small mammals

were formerly justified because of safety for human

health and conflicts with livestock for forage.”

On the other hand, Collins

et al. (1984) found it was not economically feasible to

treat prairie dogs on shortgrass rangeland with zinc

phosphide in South Dakota because the annual control

costs exceeded the value of forage gained. Seventeen

acres (6.8 ha) would have to be treated to gain 1 AUM.

Uresk (1985) reported that South Dakota prairie dog

towns treated with zinc phosphide yielded no increase in

production after 4 years. The cost-effectiveness of

prairie dog control depends greatly on the age, density,

and size ofthe prairie dog colony; soil and grassland

type; rainfall; and control method employed.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge M. J.

Boddicker and F. R. Henderson, who authored the “Prairie

Dogs” and “Black-footed Ferrets” chapters, respectively,

in the 1983 edition of Prevention and Control of

Wildlife Damage.

Figure 1 by Emily Oseas

Routman.

Figure 2 by Dave Thornhill,

University of Nebraska.

Figure 3 by Renee Lanik,

University of Nebraska.

For Additional Information

Agnew, W., D. W. Uresk, and R. M. Hansen. 1986. Flora

and fauna associated with prairie dog colonies and

adjacent ungrazed mixed-grass prairie in western South

Dakota. J. Range. Manage. 39:135-139.

Bonham, C.D., and A.

Lerwick. 1976. Vegetation changes induced by prairie

dogs on shortgrass range. J. Range Manage. 29:217-220.

Cable, K. A., and R. M.

Timm. 1988. Efficacy of deferred grazing in reducing

prairie dog reinfestation rates. Proc. Great Plains

Wildl. Damage Control Workshop 8:46-49.

Cincotta, R. P., D. W.

Uresk, and R. M. Hansen. 1987. Demography of

black-tailed prairie dog populations reoccupying sites

treated with rodenticide. Great Basin Nat. 47:339-343.

Clark, T. W. 1986.

Annotated prairie dog bibliography 1973 to 1985. Montana

Bureau Land Manage. Tech. Bull. No. 1. Helena. 32 pp.

Clark, T. W., T. M.

Campbell, III, M. H. Schroeder, and L. Richardson. 1983.

Handbook of methods for locating black-footed ferrets.

Wyoming Bureau Land Manage. Tech. Bull. No. 1. Cheyenne.

55 pp.

Committee. 1970.

Vertebrate Pests: Problems and Control. Natl. Acad. of

Science. Washington, DC. 153 pp.

Collins, A. R., J. P.

Workman, and D. W. Uresk. 1984. An economic analysis of

black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus) control.

J. Range Manage. 37:358-361.

Cox, M. K., and S. E.

Hygnstrom. 1991. Prairie dog control: a computer model

for prairie dog management on rangelands. Proc. Great

Plains Wildl. Damage Control Workshop 10:68-69.

Dobbs, T. L. 1984.

Economic losses due to prairie dogs in South Dakota.

South Dakota Dep. Agric. Div. Agric. Regs. Inspect.

Pierre. 15 pp.

Fagerstone, K. A. 1982. A

review of prairie dog diet and its variability among

animals and colonies. Proc. Great Plains Wildl. Damage

Control Workshop 5:178-184.

Franklin, W. L., and M. G.

Garrett. 1989. Nonlethal control of prairie dog colony

expansion with visual barriers. Wildl. Soc. Bull.

17:426-430.

Foster-McDonald, N. S.,

and S. E. Hygnstrom. 1990. Prairie dogs and their

ecosystem. Univ. Nebraska. Dep. For., Fish. Wildl.

Lincoln. 8 pp.

Hansen, R. M., and I.

Gold. 1977. Blacktail prairie dogs, desert cottontails

and cattle trophic relations on shortgrass range. J.

Range Manage. 30:210-214.

Hygnstrom, S. E., and P.

M. McDonald. 1989. Efficacy of three formulations of

zinc phosphide for black-tailed prairie dog control.

Proc. Great Plains Wildl. Damage Control Workshop 9:181.

Hygnstrom, S. E., and D.

R. Virchow. 1988. Prairie dogs and their control. Univ.

Nebraska-Coop. Ext. NebGuide No. C80-519. Lincoln. 4 pp.

Knowls, C. J. 1986.

Population recovery of black tailed prairie dogs

following control with zinc phosphide. J. Range Manage.

39:249-251.

Koford, C. B. 1958.

Prairie dogs, whitefaces and blue grama. Wildl. Mono.

3:1-78.

Merriam, C. H. 1902. The

prairie dog of the Great Plains. Pages 257-270 in

Yearbook of the USDA. US Govt. Print. Office.

Washington, DC.

O’Meilia, M. E., F. L.

Knopf, and J. C. Lewis. 1982. Some consequences of

competition between prairie dogs and beef cattle. J.

Range Manage. 35:580-585.

Schenbeck, G. L. 1981.

Management of black-tailed prairie dogs on the National

Grasslands. Proc. Great Plains Wildl. Damage Control

Workshop 5:207-213.

Sharps, J. C., and D. W.

Uresk. 1990. Ecological review of black-tailed prairie

dogs and associated species in western South Dakota.

Great Basin Nat. 50:339-345.

Snell, C. P., and B. D.

Hlavachick. 1980. Control of prairie dogs -the easy way.

Rangelands 2:239-240.

South Dakota Department of

Agriculture. 1981. Vertebrate rodent economic loss,

South Dakota 1980. US Dep. Agric. Stat. Rep. Serv. Sioux

Falls. 4 pp.

Uresk, D. W. 1985. Effects

of controlling black-tailed prairie dogs on plant

production. J. Range Manage. 38:466-468.

Uresk, D. W. 1987.

Relation of black-tailed prairie dogs and control

programs to vegetation, livestock, and wildlife. Pages

312-322 in J. L. Caperinera, ed. Integrated pest

management on rangeland: a shortgrass prairie

perspective. Westview Press. Boulder, Colorado.

Uresk, D. W., J. G.

MacCracken, and A. J. Bjugstad. 1982. Prairie dog

density and cattle grazing relationships. Great Plains

Wildl. Damage Control Workshop. 5:199-201.

Whicker, A. D., and J. K.

Detling. 1988. Ecological consequences of prairie dog

disturbances. BioSci. 38:778-785.

Computer

Software

Cox, M. K., and S. E.

Hygnstrom. 1993. Prairie dog control: An educational

guide, population model, and cost-benefit analysis for

prairie dog control. Available from 105 ACB IANR-CCS,

University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68583-0918.

BLACK-FOOTED FERRETS

Introduction

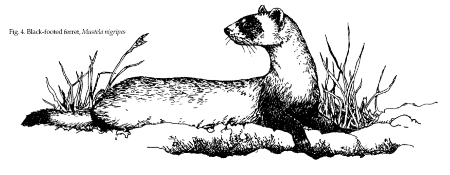

The black-footed ferret (Mustela

nigripes, Fig. 4) is the most rare and endangered mammal

in North America. Black-footed ferrets establish their

dens in prairie dog burrows and feed almost exclusively

on prairie dogs. The reduction in prairie dog numbers in

the last 100 years and the isolation and disappearance

of many large towns has led to the decline of the ferret

population. Large and healthy prairie dog towns are

needed to ensure that black-footed ferrets survive in

the wild.

Identification

Black-footed ferrets are

members of the weasel family and are the only ferret

native to North America. The most obvious distinguishing

feature is the striking black mask across the face. The

feet, legs, and tip of the tail are also black. The

remaining coat is pale yellow-brown, becoming lighter on

the under parts of the body and nearly white on the

forehead, muzzle, and throat. The top of the head and

middle of the back are a darker brown. Ferrets have

short legs, long, well-developed claws on the front

paws, large pointed ears, and relatively large eyes.

Ferrets are similar in

size and weight to wild mink. Adult male ferrets are 21

to 23 inches (53.3 to 58.4 cm) long and weigh 2 to 2 1/2

pounds (0.9 to 1.2 kg). Females are slightly smaller.

The native black-footed

ferret may be confused with the domestic European fitch

ferret, long-tailed weasel, bridled weasel, or wild mink

(Fig. 5). The domestic fitch ferret has longer and

darker pelage on the back, yellowish underfur, and an

entirely black tail. The bridled weasel is a variant of

the been released in north-central Wyoming. For the past

10 years, biologists have intensively searched for and

investigated hundreds of reports of black-footed

ferrets, but no new populations have been found. In

addition, a public reward of $5,000 to $10,000 was

available during the 1980s for sightings of black-footed

ferrets, but none were confirmed. Current efforts are

being made to identify black-footed ferret habitat and

potential reproduction sites. Captive breeding

populations are held at Wheatland, Wyoming, at the

Wyoming Game and Fish Depart-ment’s Sybille Conservation

and Education Center, and at zoos in Omaha, Nebraska;

Washington, DC; Louisville, Kentucky; Colorado Springs,

Colorado; Phoenix, Arizona; and Toronto, Ontario.

Habitat

Black-footed ferrets rely

on prairie dogs for both food and shelter. Therefore,

all active prairie dog colonies are considered potential

black-footed ferret habitat. Resident ferrets have only

been found in prairie dog towns. Transient and

dispersing ferrets may cross areas that are not occupied

by prairie dogs.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Normally 4 young ferrets

are born per litter in May and June. The mother alone

cares for the young and directs their activities until

they disperse in mid-September. The young are first

observed aboveground during daylight hours in July.

From June to mid-July, the

ferret family remains in the same general area of the

prairie dog town. Around the middle of July, after the

young are active aboveground at night, the family

extends its area of activity. By the middle of July the

young ferrets are weaned at nearly one-half adult size.

By early August, the

mother ferret separates the young and places them in

different burrows. At this time some longtail weasel. It

occurs in southwest Kansas, parts of Oklahoma, Texas,

and New Mexico. The bridled weasel has a mask or dark

markings on its face, but is smaller than a black-footed

ferret. It does not have black feet, and it has a tail

that is longer in relation to its total body length.

Mink are about the same size as black-footed ferrets but

are dark brown and occasionally have white markings on

the throat.

Range

The original range of the

black-footed ferret included most of the Great Plains

area. Its current range within the Great Plains is

unknown, although it is assumed to be greatly reduced

from the original range. Currently the only known wild

ferret population is an experimental population that has

of the young occasionally hunt at night by themselves.

By mid-August, they can be seen during daylight hours,

peering out of their burrow, playing near the entrance,

and sometimes following the adult female.

By late August or early

September, when the young are as large as the adult, the

ferret family starts to disperse and is no longer seen

as a closely knit group. The young ferrets are solitary

during the late fall, winter, and early spring. In

December, ferrets become active just after sunset and

are active at least until midnight.

Legal Status

The black-footed ferret is

classified as an endangered species and receives full

protection under the Federal Endangered Species Act of

1973 (PL 93-205). The act, as amended, requires federal

agencies to ensure that any action authorized, funded,

or carried out by them is not likely to jeopardize the

continued existence of a threatened or endangered

species or their habitat. Regulations implementing

Section 7 of the act require that federal agencies

determine if any actions they propose “may affect” any

threatened or endangered species. If it is determined

that a proposed action “may affect,” then the agency is

required to request formal Section 7 consultation with

the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Section 9 of the act

prohibits any person (including the federal government)

from the “taking” of a listed species. The term take

means to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill,

capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such

conduct. Habitat destruction constitutes the taking of a

listed species.

Guidelines for

black-footed ferret searches have been developed by the

US Fish and Wildlife Service (Blackfooted Ferret Survey

Guidelines for Compliance with the Endangered Species

Act, 1989). Federal agencies are required by the US Fish

and Wildlife Service to conduct black-footed ferret

surveys if their proposed actions may affect ferrets or

their habitat. Although encouraged to do so, private

landowners and applicators are not required by law to

conduct surveys unless their activities are associated

with federal programs or if they are specifically

directed by pesticide labels. Compliance with or

disregard for black-footed ferret survey guidelines does

not, of itself, show compliance with or violation of the

Endangered Species Act or any derived regulations.

Guidelines for Black-footed Ferret Surveys

Any actions that kill

prairie dogs or alter their habitat could prove

detrimental to ferrets occupying affected prairie dog

towns. The US Fish and Wildlife Service guidelines

should assist agencies or their authorized

representatives in designing surveys to “clear” prairie

dog towns prior to initiation of construction projects,

prairie dog control projects, or other actions that

affect prairie dogs. If these guidelines are followed by

individuals conducting black-footed ferret surveys,

agency personnel can be reasonably confident in results

that indicate black-footed ferrets are not occupying a

proposed project area.

Delineation of

Survey Areas. Until the time that wildlife

agencies are able to identify reintroduction areas and

to classify other areas as being free of ferrets,

surveys for black-footed ferrets will usually be

recommended. During this interim period the following

approach is recommended to determine where surveys are

needed.

A black-tailed prairie dog

town or complex of less than 80 acres (32 ha) having no

neighboring prairie dog towns may be developed or

treated without a ferret survey. A neighboring prairie

dog town is defined as one less than 4.3 miles (7 km)

from the nearest edge of the town being affected by a

project.

Black-tailed prairie dog

towns or complexes greater than 80 acres (32 ha) but

less than 1,000 acres (400 ha) may be cleared after a

survey for black-footed ferrets has been completed,

provided that no ferrets or ferret sign have been found.

A white-tailed prairie dog

town or complex of less than 200 acres (81 ha) having no

neighboring prairie dog towns may be cleared without a

ferret survey. White-tailed prairie dog towns or

complexes greater than 200 acres (81 ha) but less than

1,000 acres (400 ha), may be cleared after completion of

a survey for black-footed ferrets, provided that no

ferrets or their sign were found during the survey.

Contact the US Fish and

Wildlife Service before any federally funded or

permitted activities are conducted on black-tailed or

white-tailed prairie dog towns or complexes greater than

1,000 acres, to determine the status of the area for

future black-footed ferret reintroductions.

Defining a Prairie Dog

Town/ Complex

For the

purpose of this document a prairie dog town is defined

as a group of prairie dog holes in which the density

meets or exceeds 20 burrows per hectare (8

burrows/acre). Prairie dog holes need not be active to

be counted but they should be recognizable and intact;

that is, not caved in or filled with debris. A prairie

dog complex consists of two or more neighboring prairie

dog towns, each less than 4.3 miles (7 km) from the

other.

Timing of Surveys

The US Fish

and WIldlife Service recommends that surveys for

black-footed ferrets be conducted as close to the

initiation of a project construction date as possible

but not more than 1 year before the start of a proposed

action. This is recommended to minimize the chance that

a ferret might move into an area during the period

between completion of a survey and the start of a

project.

Project Type

Construction projects (buildings, facilities, surface

coal mines, transmission lines, major roadways, large

pipelines, impoundments) that permanently alter prairie

dog towns should be surveyed. Projects of a temporary

nature and those that involve only minor disturbances

(fences, some power lines, underground cables) may be

exempted from surveys when project activities are

proposed on small prairie dog towns or complexes of less

than 1,000 acres (400 ha), do not impact those areas

where ferret sightings have been frequently reported, or

occur on areas where no confirmed sightings have been

made in the last 10 years.

The US Fish and Wildlife

Service recommends that before any action involving the

use of a toxicant in or near a prairie dog town begins,

a survey for ferrets should be conducted. If toxicants

or fumigants are to be used, and the town proposed for

treatment is in a complex of less than 1,000 acres (400

ha), the town should be surveyed using the nocturnal

survey technique 30 days or less before treatment.

Prairie dog towns or complexes greater than 1,000 acres

(400 ha) should not be poisoned without first contacting

your local US Fish and Wildlife Service office.

Survey Methods

Method 1

— Daylight surveys for ferrets are recommended if

surveys are conducted between December 1 and March 31.

This type of survey is used to locate signs left by

ferrets. During winter months, ferret scats, prairie dog

skulls, and diggings are more abundant because prairie

dogs are less active and less likely to disturb or

destroy ferret sign. When there is snow cover, both

ferret tracks and fresh diggings are more obvious and

detectable.

Daylight searches for

ferret sign should meet the following criteria to

fulfill the minimum standards of these guidelines:

-

Three searches must be

made on each town. Conduct each search when fresh

snow has been present for at least 24 hours and

after 10 or more days have passed between each

search period.

-

Vehicles driven at

less than 5 miles per hour (8.3 km/hr) may be used

to search for tracks or ferret diggings, but

complete visual inspections of each part of the town

being surveyed is required (that is, visually

overlapping transects).

-

If ferret sign is

observed, photograph the sign and make drawings and

measurements of diggings before contacting the US

Fish and Wildlife Service and state wildlife agency.

Method 2 —

Nighttime surveys involve the use of spotlighting

techniques for locating ferrets. This survey method is

designed to locate ferrets when the maximum population

and the longest periods of ferret activity are expected

to occur.

Minimum standards should

be followed as recommended below:

-

Conduct surveys

between July 1 and October 31.

-

Continuously survey

the prairie dog town using spotlights. Begin surveys

at dusk and continue until dawn on each of at least

3 consecutive nights. Divide large prairie dog

colonies into tracts of 320 acres (130 ha) and

search each tract systematically throughout 3

consecutive nights. Rough uneven terrain and tall

dense vegetation may require smaller tracts to

result in effective coverage of a town.

-

Begin observations on

each prairie dog town or tract at a different

starting point on each successive night to maximize

the chance of overlapping nighttime activity periods

of ferrets.

-

A survey crew should

consist of one vehicle and two observers equipped

with two 200,000 to 300,000 candlepower (lumen)

spotlights. In terrain not suitable for vehicles, a

crew should consist of two individuals working on

foot with battery-powered 200,000 to 300,000

candlepower (lumen) spotlights. To estimate the

number of crew nights for a survey, divide the total

area of prairie dog town to be surveyed by 320 acres

(130 km) and multiply by 3. One or both of the

observers in each survey crew should be a biologist

trained in ferret search techniques.

Additional information on

data collection, reporting, and training workshops are

included in Black-footed Ferret Survey Guidelines for

Compliance with the Endangered Species Act, 1989,

available from the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Black-footed Ferret Sign

To determine if

black-footed ferrets are living in a given area, some

sign must be found or a ferret observed. Evidence such

as tracks, diggings, or droppings is uncommon, even

where ferrets occur. They are secretive, nocturnal, and

inactive for long periods of time, and therefore are

very seldom seen by people.

Prairie dogs compact the

soil around their burrows, making it difficult to find

ferret tracks. Most ferret tracks are observed when snow

covers the ground. The average distance between each

“twin print” track in the normal bounding gait is 12 to

16 inches (30.5 to 40.6 cm) (Fig. 6). The track of a

ferret is very similar to that of a mink or weasel. In

Wyoming, ferrets are most active between December and

early March, sometimes covering up to 5 miles (8 km) per

night. Scent marks, scrapes, and scratches in the snow

may be noticeable. Ferret droppings are rarely found

above ground. They are long and thin, taper on both

ends, and consist almost entirely of prairie dog hair

and bones.

Ferrets sometimes form

“trenches” or “ramps” when they excavate prairie dog

burrows. Prairie dogs occasionally plug the entrances to

their burrow systems with soil. When excavating such a

plug in a burrow, the ferret backs out with the soil

held against its chest with its front paws. It generally

comes out of the burrow in the same path each time. This

usually occurs when snow covers the ground. After

repeated trips, a ramp from 3 to 5 inches (7.6 to 12.7

cm) wide and from 1 to 9 feet (0.3 to 2.7m) long is

formed (Fig. 7). Badgers, foxes, and weasels

occasionally form similar ramps.

Prairie dogs generally

deposit excavated soil around the burrow entrance to

form a mound, building it higher by adding soil from

outside the mound. The movement of soil toward the mound

is in the opposite direction of that done by a ferret.

Ferrets sometimes dig in

fresh snow. These "snow trenches are narrow trough-like

depressions in the snow that extend away from prairie

dog burrow entrances. Snow trenches are relatively rare

compared to trenches in the soil.

If you observe a

black-footed ferret or identify ferret sign while

conducting surveys, notify your local US Fish Wildlife

Service or state wildlife representative within 24

hours.

Acknowledgments

Figures 4 and 5 by Emily

Oseas Routman.

Figure 6 courtesy of

Thomas M. Campbell III, Biota Research and Consulting

Service.

Figure 7 courtesy of Walt

Kittams.

For Additional Information

Biggins, P.E., and R.A.

Crete. 1989. Black-footed ferret recovery. Proc. Great

Plains Wildl. Damage Control Workshop 9:59-63.

Clark, T.W., T.M.

Campbell, III, M.H. Schroeder, and L. Richardson. 1984.

Handbook of methods for location of black-footed

ferrets. Wyoming BLM Wildl. Tech. Bull. No. 1. US Bureau

Land Manage., in coop. with Wyoming Game Fish Comm.

Cheyenne. 47 pp.

Hall, E.R. 1981. The

mammals of North America. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

1181 pp.

Hillman, C.N. 1968. Field

observations of black-footed ferrets in South Dakota.

Trans. North Am. Wildl. Nat. Resour. Conf. 33:346-349.

Hillman, C.N. 1974. Status

of the black-footed ferret. Pages 75-81 in Proc. symp.

endangered and threatened species of North America. Wild

Canid Survival Res. Center. St. Louis, Missouri.

Hillman, C.N., and T.W.

Clark. 1980. Mustela nigripes. Mammal. Species 126:1-3.

Hillman, C.N., and R.L.

Linder. 1973. The black-footed ferret. Pages 10-23 in R.

L. Linder and C. N. Hillman, eds. Proc. black-footed

ferret and prairie dog workshop. South Dakota State

Univ., Brookings.

Sheets, R.C., R.L. Linder,

and R.B. Dahlgren. 1972. Food habits of two litters of

black-footed ferrets in South Dakota. Am. Midl. Nat.

87:249-251.

US Fish and Wildlife

Service. 1988. Black-footed ferret recovery plan. US

Fish Wildl. Serv., Denver, Colorado. 154 pp.

US Fish and Wildlife

Service. 1989. Black-footed ferret survey guidelines for

compliance with the endangered species act. US Fish

Wildl. Serv. Denver, Colorado, 15 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom, Robert

M. Timm, Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

04/05/2006

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|