|

|

|

|

|

RODENTS: Porcupines |

|

|

Fig. 1. Porcupine,

Erethizon dorsatum

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

- Exclusion

- Fences (small

areas). Tree trunk guards.

- Cultural Methods

- Encourage

closed-canopy forest stands.

- Repellents

- None are

registered.

- Some wood

preservatives may incidentally repel porcupines.

- Toxicants

- None are

registered.

- Fumigants

- None are

registered.

- Trapping

- Steel leghold trap

(No. 2 or 3). Body-gripping (Conibear®) trap (No.

220 or 330). Box trap.

- Shooting

- Day shooting and

spotlighting are effective where legal.

- Other Methods

- Encourage natural

predators.

Identification

Porcupines (Erethizon

dorsatum), sometimes called “porkies” or “quill pigs,”

(Fig. 1) are heavy-bodied, short-legged, slow, and

awkward rodents, with a waddling gait. Adults are

typically 25 to 30 inches (64 to 76 cm) long and weigh

10 to 30 pounds (4.5 to 13.5 kg). They rely on their

sharp, barbed quills (up to 30,000 per individual) for

defense.

Range

and Habitat Range

and Habitat

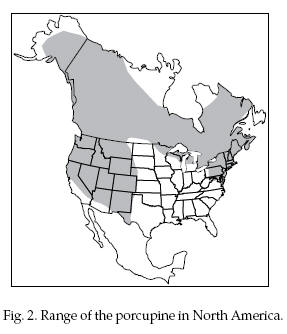

The porcupine is a common

resident of the coniferous forests of western and

northern North America (Fig. 2) It wanders widely and is

found from cottonwood stands along prairie river bottoms

and deserts to alpine tundra.

Food Habits

Porcupines eat herbaceous

plants, inner tree bark, twigs, and leaves, with an

apparent preference for ponderosa pine, aspen, willow,

and cottonwood. Trees with thin, smooth bark are

preferred over those with thick, rough bark. Porcupine

feeding is frequently evident and has considerable

impact on the cottonwood stands of western river

bottoms.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Porcupines breed in

autumn, and after a 7-month gestation period usually

produce 1 offspring in spring. Although the young are

capable of eating vegetation within a week after birth,

they generally stay with the female through the summer.

Juvenile survival rates are high.

Predators of porcupines

include coyotes, bobcats, mountain lions, black bears,

fishers, martens, great horned owls, and others. Coyote

scats (feces) containing large numbers of quills are not

unusual. How the quills are maneuvered through the

coyote’s gastrointestinal tract is a mystery.

Porcupines are active

year-round and are primarily nocturnal, often resting in

trees during the day. They favor caves, rock slides, and

thick timber downfalls for shelter.

Damage and Damage Identification

Clipped

twigs on fresh snow, tracks, and gnawings on trees are

useful means of damage identification (Fig. 3). Trees

are often deformed from partial girdling. Porcupines

clip twigs and branches that fall to the ground or onto

snow and often provide food for deer and other mammals.

The considerable secondary effects of their feeding come

from exposing the tree sapwood to attack by disease,

insects, and birds. This exposure is important to many

species of wildlife because diseased or hollow trees

provide shelter and nest sites. Clipped

twigs on fresh snow, tracks, and gnawings on trees are

useful means of damage identification (Fig. 3). Trees

are often deformed from partial girdling. Porcupines

clip twigs and branches that fall to the ground or onto

snow and often provide food for deer and other mammals.

The considerable secondary effects of their feeding come

from exposing the tree sapwood to attack by disease,

insects, and birds. This exposure is important to many

species of wildlife because diseased or hollow trees

provide shelter and nest sites.

Porcupines occasionally

will cause considerable losses by damaging fruits, sweet

corn, alfalfa, and small grains. They chew on hand tools

and other wood objects while seeking salt. They destroy

siding on cabins when seeking plywood resins.

Porcupines offer a

considerable threat to dogs, which never seem to learn

to avoid them. Domestic stock occasionally will nuzzle a

porcupine and may be fatally injured if quills are not

removed promptly.

Legal Status

Porcupines are considered

nongame animals and are not protected.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Fencing small tree plantings, orchards, and gardens

is effective in reducing porcupine damage. Electric

fences are effective when the smooth electric wire is

placed 1 1/2 inches (3.8 cm) above 18-inch-high (46-cm)

poultry wire. A 4- to 6-inch (10-to 15-cm) electric

fence can be enhanced by painting molasses on the wire.

Porcupines will climb fences, but an overhanging wire

strip around the top of the fence at a 65o angle to the

upright wire will discourage them.

Completely enclose small

trees with wire baskets or encircle the trunks of fruit

and ornamental trees with 30-inch (70-cm) bands of

aluminum flashing to reduce damage.

Cultural Methods

Thinned forest stands are vulnerable to porcupine

damage because lower vegetation can thrive. Porcupine

populations are usually lower in closed canopy stands

where understory vegetation is scant.

Repellents

Thiram is registered as a squirrel and rabbit repellent

and may incidentally repel porcupines. This material is

sprayed or painted on the plants subject to damage. It

must be renewed occasionally to remain effective. Common

wood preservatives may repel porcupines when applied to

exterior plywoods. Avoid using wood preservatives that

are metal-salt solutions. These will attract porcupines.

Toxicants

No toxicants can be legally used to control

porcupines.

Trapping

Steel leghold traps of size No. 2 or 3 can be used

to catch porcupines where legal. Cubby sets with salt

baits, trail sets in front of dens, and coyote urine

scent post sets near dens and damage activity are

effective. Scent post and trail sets must be checked

daily to release nontarget animals that might be caught.

Leghold traps should be bedded, firmly placed and

leveled, and offset slightly to the side of the trail.

The trapped porcupine can be shot or killed by a sharp

blow to the head.

The No. 220 or 330

Conibear® body-gripping trap can be baited with a

salt-soaked material or placed in den entrances to catch

and kill porcupines. Care must be taken to avoid taking

nontarget animals, since salt attracts many animals. The

Conibear® trap does not allow the release of accidental

catches. Some states do not allow the use of No. 330

Conibear® traps for ground sets.

Porcupines are rather easy

to livetrap with large commercial cage traps (32 x 10 x

12 inches [81 x 25 x 30.5 cm]) or homemade box traps.

Place the live trap in the vicinity of damage and bait

with a salt-soaked cloth, sponge, or piece of wood. Live

traps also can be set at den entrances. Move the

porcupine 25 miles (40 km) or more to ensure that it

does not return. Since most areas of suitable habitat

carry large porcupine populations, relocation of the

porcupine often is neither helpful nor humane since the

introduced animal may have a poor chance of survival.

Shooting

Persistent hunting and shooting of porcupines can be

effective in reducing the population in areas that

require protection. Night hunting, where legal, is

effective. During winter months, porcupines are active

and can be tracked in the snow and shot with a

.22-caliber rifle or pistol. Porcupines often congregate

around good denning sites and extensively girdle trees

in the area. In such places large numbers may be taken

by shooting.

Other Considerations

Porcupines are mobile and continually reinvade

control areas. Complete control is not desirable since

it would require complete removal of porcupines. Try to

limit lethal porcupine control to individual animals

causing damage by fencing and management of the plant

species. In areas of high porcupine populations, plant

ornamentals that are not preferred foods. Intensive

predator control may encourage porcupine population

increases.

Economics of Damage and Control

Economic losses can be

considerable from porcupines feeding on forest

plantings, ornamentals, and orchards as well as on

leather and other human implements. Porcupines generally

are tolerated except when commercial timber, high-value

ornamental plantings, orchards, or nursery plants are

damaged by girdling, basal gnawing, or branch clipping.

On occasion, porcupines thin dense, crowded forest

stands. Often tree diameter growth is reduced. Their

preference for mistletoe as a food is an asset.

The porcupine is acclaimed

as a beautiful creature of nature. It is an interesting

animal that has an important place in the environment.

It is edible and has been used by humans as an emergency

food. The quills are used for decorations, especially by

Native Americans. The hair, currently used for

fly-fishing lures, commands many dollars per ounce.

Porcupines are not wary and can be readily observed and

photographed by nature lovers. Porcupines may need to be

controlled but should not be totally eradicated.

Acknowledgments

Some of the information

for this chapter was taken from a chapter by Major L.

Boddicker in the 1980 edition of Prevention and Control

of Wildlife Damage.

Figure 1 by Emily Oseas

Routman.

Figure 2 adapted from Burt

and Grossenheider (1976) by Jill Sack Johnson.

Figure 3 adapted from

Murie (1954) by Renee Lanik, University of

Nebraska-Lincoln.

For Additional Information

Burt, W. H., and R. P.

Grossenheider. 1976. A field guide to the mammals, 3d

ed. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. 289 pp.

Clark, J. P. 1986.

Vertebrate pest control handbook. California Dep. Food

and Agric. Sacramento. 615 pp.

Dodge, W. E. 1982.

Porcupine. Pages 355-366 in J. A. Chapman and G. A.

Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North America: biology,

management, and economics. The Johns Hopkins Univ.

Press. Baltimore.

Marsh, R. E., and W. E.

Howard. 1977. Vertebrate control manual. Pest Control

45:28-31.

Murie, O. J. 1954. A field

guide to animal tracks. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston.

375 pp.

Roze, V. 1989. The North

American porcupine. Smithsonian Press, Washington, DC.

261 pp.

Spencer, D. A. 1948. An

electric fence for use in checking porcupine and other

mammalian crop depredations. J. Wildl. Manage.

12:110-111.

Woods, C. A. 1978.

Erethizon dorsatum. Mammal. Sp. 29:1-6.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom, Robert

M. Timm, Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

10/18/2005

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|