|

|

|

|

|

RODENTS: Kangaroo Rats |

|

|

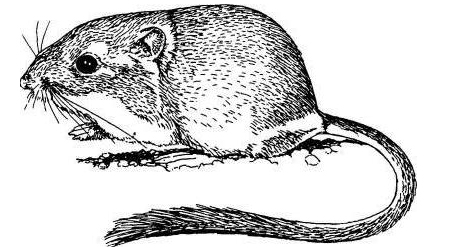

Fig. 1. The Ord’s kangaroo

rat, Dipodomys ordi

Identification

and Range Identification

and Range

There are 23 species of

kangaroo rats (genus Dipodomys) in North America.

Fourteen species occur in the lower 48 states. The Ord’s

kangaroo rat (D. ordi, Fig. 1) occurs in 17 US states,

Canada, and Mexico. Other widespread species include the

Merriam kangaroo rat (D. merriami), bannertail kangaroo

rat (D. spectabilis), desert kangaroo rat (D. deserti),

and Great Basin kangaroo rat (D. microps). Kangaroo rats

are distinctive rodents with small forelegs; long,

powerful hind legs; long, tufted tails; and a pair of

external, fur-lined cheek pouches similar to those of

pocket gophers. They vary from pale cinnamon buff to a

dark gray on the back with pure white underparts and

dark markings on the face and tail. The largest, the

giant kangaroo rat (D. ingens), has a head and body

about 6 inches (15 cm) long with a tail about 8 inches

(20 cm) long. The bannertail kangaroo rat is

approximately the same size, but has a white-tipped

tail. The other common species of kangaroo rats are

smaller. The Ord’s kangaroo rat has a head and body

about 4 inches (10 cm) long and a tail about 7 inches

(18 cm) long.

Habitat

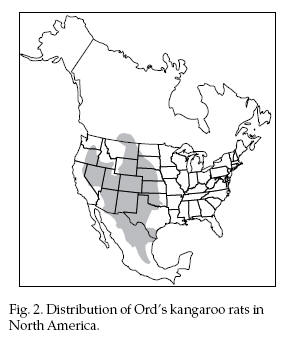

Kangaroo rats inhabit semiarid and arid

regions throughout most of the western and plains

states. The Ord’s kangaroo rat is the most common and

widespread of the kangaroo rats (Fig. 2). Several other

species are located in Mexico, California, and the

southwestern United States. They generally are not found

in irrigated pastures or crops, but may be found

adjacent to these areas on native rangelands, especially

on sandy or soft soils. They also invade croplands under

minimum tillage in these areas, particularly areas under

dry farming.

Food Habits

Kangaroo rats are primarily seed eaters, but

occasionally they will eat the vegetative parts of

plants. At certain times of the year they may eat

insects. They have a strong hoarding habit and will

gather large numbers of seeds in their cheek pouches and

take them to their burrows for storage. This caching

activity can cause significant impact on rangeland and

cropland. They remove seeds from a large area, thus

preventing germination of plants, particularly grasses,

in succeeding years. Since these rodents do not

hibernate, the seed caches are a source of food during

severe winter storms or unusually hot summer weather.

Kangaroo rats are quite sensitive to extremes in

temperature and during inclement weather may remain

underground for several days.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Kangaroo rats breed from

February to October in southern desert states. The

breeding period is shorter in the northern states. The

gestation period is approximately 30 days. Reproductive

rates vary according to species, food availability, and

density of rodent populations. Females have 1 to 3

litters of 1 to 6 young per year. The young are born

hairless and blind in a fur-lined nest within the tunnel

system. Usually, the young remain in the nest and tunnel

for nearly a month before appearing aboveground.

Only a few females will

breed after a prolonged drought when food is in short

supply. Most females will bear young when food is

abundant, and some young females born early in the

season will also produce litters before the season ends.

All kangaroo rats build

tunnels in sandy or soft soil. The tunnel system is

fairly intricate, and consists of several sleeping,

living, and food storage chambers. The extensive

burrowing results in a fair amount of soil being brought

up and mounded on the ground surface. These mounds can

be mistaken for prairie dog mounds, particularly when

observed on aerial photographs. They may vary in size

but can be as large as 15 feet (4.5 m) across and up to

2 feet (60 cm) high.

Kangaroo rats are

completely nocturnal and often plug their burrow

entrances with soil during the day to maintain a more

constant temperature and relative humidity. They are

often seen on roads at night, hopping in front of

headlights in areas where they occur.

Kangaroo rats often occur

in aggregations or colonies, but there appears to be

little if any social organization among them. Burrows

are spaced to allow for adequate food sources within

normal travel distances. Spacing of mounds will vary

according to abundance of food, but well-defined travel

lanes have been observed between neighboring mounds.

When kangaroo rats are

locally abundant, their mounds, burrow openings, and

trails in vegetation and sand are conspicuous features

of the terrain. Both the number of burrows and

individuals per acre (ha) can vary greatly depending on

locality and time of year. There are usually many more

burrow openings than there are rats. Each active burrow

system, however, will contain at least one adult rat.

There could be as many as 35 rats per acre (14/ha) in

farmlands. In rangelands, 10 to 12 rats per acre (4 to

5/ha) is more likely. Kangaroo rats do not have large

home ranges; their radius of activity is commonly 200 to

300 feet (60 to 90 m), rarely exceeding 600 feet (183

m). They may move nearly a mile (1.6 km) to establish a

new home range.

Damage and Damage Identification

Historically, kangaroo

rats were considered to be of relatively minor economic

importance. They have come into direct conflict with

human interests, however, with large-scale development

of sandy soil areas for sprinkler-irrigated corn and

alfalfa production. A primary conflict develops at

planting time when kangaroo rats dig up newly planted

seeds and clip off new sprouts at their base. Damage is

more severe when population densities are high. Smaller

populations apparently are able to subsist on waste

grain and damage is not as apparent. Since kangaroo rats

are primarily seed eaters, they find irrigated fields

and pastures a veritable oasis and feed extensively on

waste grain after harvest.

Kangaroo rats have foiled

attempts to restore overused rangelands. Their habit of

collecting and caching large numbers of grass seeds

restricts the natural reseeding process. In semiarid

rangelands, activities of kangaroo rats can prevent an

area from making any appreciable recovery even though

the area received complete rest from livestock grazing

for 5 years or more. Reducing livestock grazing is not

enough. As long as kangaroo rats remain in an area, they

will restrict the reestablishment of desirable forages,

particularly native grasses.

Legal Status

Most kangaroo rats are

considered nongame animals and are not protected by

state game laws. Certain local subspecies may be

protected by regulations regarding threatened and

endangered species. Consult local authorities to

determine their legal status before applying controls.

Attention!!

Five kangaroo rat species currently are listed as

endangered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service. They are

found mostly in California and include the Fresno

kangaroo rat (D. nitratoides exilis), giant kangaroo rat

(D. ingens), Morro Bay kangaroo rat (D. heermanni

morroensis), Stephens’ kangaroo rat (D. stephensi

including D. cascus), and Tipton kangaroo rat (D.

nitratoides nitratoides). Persons working in California,

southern Oregon, south central Nevada, and western

Arizona should have expertise in identifying these

species, their mounds, and the ranges in which they

likely occur.

Damage Prevention and Control

Exclusion

Exclusion is most often accomplished by the

construction of rat-proof fences and gates around the

area to be protected. Most kangaroo rats can be excluded

by 1/2-inch (1.3-cm) mesh hardware cloth, 30 to 36

inches (75 to 90 cm) high. The bottom 6 inches (15 cm)

should be turned outward and buried at least 12 inches

(30 cm) in the ground. Exclusion may be practical for

small areas of high-value crops, such as gardens, but is

impractical and too expensive for larger acreages.

Cultural Methods

Alfalfa, corn, sorghum, and other grains are the

most likely crops to be damaged by kangaroo rats. When

possible, planting should be done in early spring before

kangaroo rats become active to prevent loss of seeds.

Less palatable crops should be planted along field edges

that are near areas infested with kangaroo rats.

High kangaroo rat numbers

most often occur on rangelands that have been subjected

to overuse by livestock. Kangaroo rats usually are not

abundant where rangelands have a good grass cover, since

many of the forbs that provide seeds for food are not

abundant in dense stands of grass. Thus, changes in

grazing practices accompanied by control programs may be

necessary for substantial, long-term relief.

Repellents

There are no registered repellents for kangaroo

rats.

Toxicants

Zinc Phosphide. At present, 2% zinc phosphide bait

is federally registered for the control of the

bannertail, Merriam, and Ord’s kangaroo rats in

rangeland vegetation and noncrop areas. Some states may

also have Special Local Needs 24(c) registrations for

zinc phosphide baits to control kangaroo rats.

Zinc phosphide pelleted

rodent bait was tested on kangaroo rats in New Mexico

(Howard and Bodenchuk 1984). Levels of control were much

lower than those for 0.5% strychnine oats, but higher

than for 0.16% strychnine oats. Zinc phosphide applied

in June produced the highest percentage of control. Zinc

phosphide is advantageous because it is thought to

present little or no hazard of secondary poisoning to

small canids and a low hazard to other nontarget

wildlife.

Carefully read and follow

all label instructions. Zinc phosphide is a Restricted

Use Pesticide for retail sale to and use by certified

applicators or persons under their direct supervision,

and only for those uses covered by the applicator’s

certification.

Fumigants

There are no fumigants registered specifically for

kangaroo rats. Aluminum phosphide and gas cartridges are

currently registered for “burrowing rodents such as

woodchucks, prairie dogs, gophers, and ground

squirrels.”

Trapping

Live Traps. Trapping with box-type (wire

cage) traps can be successful in a small area when a

small number of kangaroo rats are causing problems.

These traps can be baited successfully with various

grains, oatmeal, oatmeal and peanut butter, and other

baits. One problem is the disposal of kangaroo rats

after they have been trapped. They usually die from

exposure if they remain in the trap for over 6 hours. If

the rats are released, they should be taken to an area

more than 1 mile (1.6 km) from the problem site. The

release site should provide suitable habitat and be

acceptable to everyone involved. Do not release kangaroo

rats in areas where landowners do not want them.

Snap Traps.

Trapping with snap traps is probably the most efficient

and humane method for kangaroo rats. Mouse traps will

suffice for smaller animals, but Victor® “museum

specials” or rat traps are needed for larger kangaroo

rats, particularly the bannertail. Successful baits

include whole kernel corn, peanut butter and oatmeal,

and oatmeal paste, which are placed on the trigger

mechanism. Place traps near, but not inside, the burrow

entrances or along runways between mounds. Check traps

each day to remove dead kangaroo rats. Reset tripped

traps and replace baits that may have been removed by

ants or other insects. Do not use whole kernel corn when

large numbers of seed-eating songbirds are in the area.

Other Methods

If kangaroo rats from only

one or two mounds are causing the problems, and water is

available, they may be flushed from their burrows and

either killed or allowed to go elsewhere. Collapse the

mounds after the kangaroo rats have been driven out.

This not only levels the surface but also allows you to

detect burrow reinvasion by other kangarooa rats. Use

caution when flushing burrows with water or trapping

kangaroo rats. The burrow entrances are sometimes used

by rattlesnakes seeking to escape heat and direct

sunlight during hot days. Even on warm days,

rattlesnakes may be found near mounds since kangaroo

rats are a source of food for them.

Economics of Damage and Control

Wood (1969) found that

Ord’s kangaroo rats eat about 1,300 pounds (585 kg) of

air-dried plant material per section per year in south

central New Mexico based on average (medium) densities.

He also reported an additional 336 pounds (151 kg) of

air-dried plant material per section per year consumed

by bannertail kangaroo rats in the same area under

average (medium) population densities. These data were

for arid rangelands and could be higher if the

populations of either species were denser. This forage

loss (3 Animal Unit Months [AUMs]) is currently valued

at $6 to $12 per section in New Mexico.

Bannertail kangaroo rats

stored 2.9 tons (2.6 mt) of plant material per section

per year in their burrows. Furthermore, production of

grasses on rangelands in excellent condition were

reduced by 10.6% (or 12 AUMs) by denuding of areas in

the vicinity of kangaroo rat mounds. These estimates do

not include the loss of regeneration of desirable

grasses due to seed consumption.

In areas that are being

farmed for production of pasture or commercial crops,

densities of kangaroo rats could become much higher than

those reported by Wood (1969). These higher densities,

coupled with higher crop values, could conceivably

produce losses greater than $100 per acre ($250/ha).

The cost of controlling

kangaroo rats can be quite high if labor-intensive

methods are employed. Of course, the cost per mound will

be higher when controlling a few mounds rather than

larger numbers. Trapping is the most costly method;

toxicants the least costly. The cost of the traps varies

greatly, depending on the size, number, and kind of

traps used. Live traps cost more than snap traps. The

cost of toxic baits is relatively low on a per-mound

basis. Labor costs are reduced when large areas are

treated with toxic grain baits using a four-wheel,

all-terrain cycle.

Information on specific

control techniques and limitations can be obtained from

your local extension agent or extension wildlife

specialist. In addition, personnel from state wildlife

agencies or USDA-APHIS-ADC can provide information on

control measures available in your area.

Acknowledgments

Figure 1 by Emily Oseas

Routman.

Figure 2 adapted by the

author from Burt and Grossenheider (1976).

For

Additional Information

Burt, W. H., and R. P.

Grossenheider. 1976. A field guide to the mammals, 3d

ed. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, 289 pp.

Eisenbert, J. F. 1963. The

behavior of heteromyid rodents. Univ. California Publ.

Zool. 69:1-100. P>

Howard, V. W., Jr., and M.

J. Bodenchuk. 1984. Control of kangaroo rats with poison

baits. New Mexico State Univ. Range Improv. Task Force.

Res. Rep. 16.

Wood, J. E. 1965. Response

of rodent populations to controls. J. Wildl. Manage.

29:425-438.

Wood, J. E. 1969. Rodent

populations and their impact on desert rangelands. New

Mexico Agric. Exper. Stn. Bull. 555. 17 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom, Robert

M. Timm, Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska - Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|