|

|

|

|

|

REPTILES, AMPHIBIANS, ETC: Turtles |

|

|

Fig. 1. Eastern box

turtle, Terrapene carolina

Identification and Range

Turtles occur on all

continents except Antarctica. Over 240 species occur

worldwide but turtles are most abundant in eastern North

America. Most turtles have good field characteristics

that are visible and can be easily identified. Some

species, however, require close examination of the

shields on the plastron (underside shell) for a positive

identification.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Any permanent body of

water is a potential home for turtles. Some species will

also tolerate brackish water, but the sea turtles are

the only true saltwater species.

Unlike most other turtles,

including soft-shells, snapping turtles rarely bask.

Turtles feed on a combination of plant and animal

material that includes items such as aquatic weeds,

crayfish, carrion, insects, fish, and other small

organisms. The diet of snapping turtles, however,

usually includes a relatively high proportion of fish.

They are relatively aggressive predators, occasionally

known to take fish off fish stringers.

All turtles reproduce by

laying eggs in early spring. Hatching begins in late

summer and extends into the fall, depending on summer

temperatures associated with the climate of the range.

During winter, turtles usually bury themselves in soft

mud or sand in shallow water with only the eyes and

snout exposed.

Turtles are easy prey for

a number of predator species such as alligators, otters,

raccoons, and bears. Humans are probably the greatest

threat to turtle populations, particularly for the most

commercial species, such as snappers and soft-shells.

Damage

Turtles are seldom a pest

to people. Turtles are very beneficial and of economic

importance, except in certain areas such as waterfowl

sanctuaries, aquaculture facilities, and rice fields in

the south. Indiscriminate destruction of turtles is

strongly discouraged, and every effort should be made to

ensure that local populations are not exterminated

unless it can be clearly demonstrated that they are

undesirable.

Some species of pond and

marsh turtles are occasional economic pests in rice

fields in the south. Their feeding activity on young

rice often results in significant yield reductions in

local areas.

In farm ponds, turtles

undoubtedly compete with fish for natural food sources

such as crayfish and insects. Turtles, however, are

valuable because they kill diseased and weakened fish,

and clean up dead or decaying animal matter.

In commercial aquaculture

production ponds, turtles can eat fish that are being

grown. They also eat fish food. Aquaculture ponds are

not the preferred habitat of turtles, however. The heavy

clay soils required for pond construction are not

conducive to the turtles’ laying of eggs.

Legal Status

Most turtles are not

protected by state laws. Licenses usually are required

for commercial fishing and sale of turtles. Before

taking turtles, contact a state wildlife or conservation

agency representative for legal status.

There were two turtles

listed by the US Fish and Wildlife Service as endangered

or threatened species as of December 1992. The desert

tortoise was listed as threatened everywhere except for

a population in Arizona. Its historic range is Arizona,

California, Nevada, and Utah. The gopher tortoise was

listed as threatened wherever found west of the Mobile

and Tombigbee rivers in Alabama, Mississippi, and

Louisiana. Its historic range is Alabama, Florida,

Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina.

Five freshwater turtles

were listed by the US Fish and Wildlife Service as

endangered or threatened species as of December 1992.

The Alabama red-bellied turtle and the flattened musk

turtle were listed as endangered and threatened,

respectively. Alabama is the historic range of both

species. The ringed sawback turtle is threatened in its

historic range of Louisiana and Mississippi. The

yellow-blotched map turtle is threatened in its historic

range of Mississippi. The Plymouth red-bellied turtle is

endangered in its historic range of Massachusetts.

Additional species under

review include the alligator snapping turtle, bog

turtles, and the western tortoises.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Cultural Methods

The best control for box,

pond, and marsh turtles in rice fields is to drain

irrigation canals and fallow fields during winter

months. Without a permanent water source year-round,

these species do not reach large enough populations to

become a serious economic problem.

Ponds that are used for

the production of channel catfish or other finfish are

routinely harvested by seining. The seining process will

also capture turtles. Farmers can control turtle

populations by moving these captured turtles to their

natural habitats.

Repellents, Toxicants, and

Fumigants

None are registered.

Trapping

Since turtles generally

are not a pest to people, control measures are limited

primarily to trapping. Trapping can be used quite

effectively to reduce local populations of these species

where damage occurs.

The best place to trap

turtles is in the quiet water areas of streams and

ponds, or in the shallow water of lakes. Soft-bottom

areas near aquatic vegetation are excellent spots.

The best seasons for

trapping are spring, summer, and early fall. Most

turtles hibernate through the winter, except in the

extreme south, and do not feed, making trapping

ineffective. Methods of trapping are described for

various types of turtles in the following sections.

Traps should be baited

with fresh fish or red meat. Catfish heads and cut carp

are regarded as two of the best baits available for

trapping turtles. Baits should be suspended in traps on

a bait hook or placed in bait containers for maximum

effectiveness. In areas where turtle populations are

high, it is often necessary to check traps two or three

times per day and add fresh bait, since turtles are

capable of consuming large quantities of bait rather

quickly.

Snapping and Soft-Shell

Turtles.

While snapping turtles are

in hibernation, they often can be taken in quantities

from spring holes and old muskrat holes, under old logs,

and in soft bottoms of waterways. Turtle collectors rely

on their hunting instincts and experience to locate

hibernating turtles. When one is found, it pays to

explore the surrounding area carefully because snappers

often hibernate together. The method for capture, known

as noodling or snagging, requires a stout hook. One end

of an iron rod is bent to form a hook and sharpened; the

other end of the rod is used for probing into the mud or

soil to locate the turtles. The hunter probes about in

the mud bottom until a turtle is located (which feels

much like a piece of wood) and then pulls it out with

the hook. Turtles are inactive during the winter and

offer little resistance to capture, although the landing

of large ones may be difficult even for experienced

hunters.

Snappers and soft-shelled

turtles are sometimes taken on set lines baited with cut

fish or other fresh meat. One recommended device is made

by tying 4 or 5 feet (1.2 or 1.5 m) of line to a stout

flexible pole, 6 to 8 feet (1.8 to 2.4 m) long. About 12

inches (30.5 cm) of No. 16 steel wire is placed between

the line and the hook, preferably a stout hook about 1

inch (2.5 cm) across between barb and shaft. The end of

the pole is pushed into the bank far enough to make it

secure at an angle that will hold the bait a few inches

(cm) above the bottom.

Snappers and soft-shelled

turtles may also be taken readily in baited fyke or hoop

nets (Fig. 2). These barrel-shaped traps may sometimes

be purchased on the market or made from 3-inch (7.6- cm)

square mesh of No. 24 nylon seine twine. The trap should

be 4 to 6 feet (1.2 to 1.8 m) long from front to back

hoop. The three to five hoops per trap be approximately

30 inches (76 cm) in diameter, made of wood or 6-gauge

steel wire with welded joints. The funnel-shaped mouth

should be 18 inches (46 cm) deep from the front hoop to

the opening inside. The entrance opening of the funnel

should be 1 inch x 20 inches (2.5 x 51 cm). The corners

of the opening are tied by twine to the middle hoop. The

rear or box end may be closed with a purse string. After

the hoops have been installed, the net should be treated

with a preservative of tanbark, cooper oleate, tar, or

asphalt. To keep the trap extended, stretchers of wood

or steel wire, about 9 gauge or larger, are fastened

along each side.

Coarse mesh poultry wire

may be substituted for the twine. If this is done, the

frame will be approximately 30 inches (76 cm) square.

The shape and dimensions of the entrance as specified

should be the same in all traps, as it is easily

negotiated by the turtles. The dimensions of the trap

may be altered for ease of transportation. A door may be

installed in the top to facilitate baiting and removal

of turtles. Entrance funnels may be placed on each end

if desired.

Fyke or hoop turtle traps

should be set with the tops of the hoops just out of the

water. This will permit the turtles to obtain air and

lessen their struggles to escape, and will enable other

turtles to enter the trap more freely. It is necessary

to set traps this way if the turtles are to be taken

alive. Traps set in streams must be anchored. If the

water is too deep for the top of the trap to be out of

the water, short logs can be lashed to each side to

float the trap. Turtles enter more readily when the

mouth of the trap is set downstream.

Box, Pond, and Marsh

Turtles. Because of their habits, these species must

be captured with methods different from those for

snapping and softshelled turtles. They cannot be taken

in numbers during the winter, like snappers, because

they do not congregate in their hibernating places. In

the summer some species are gregarious, crowding

together in numbers on projecting logs and banks.

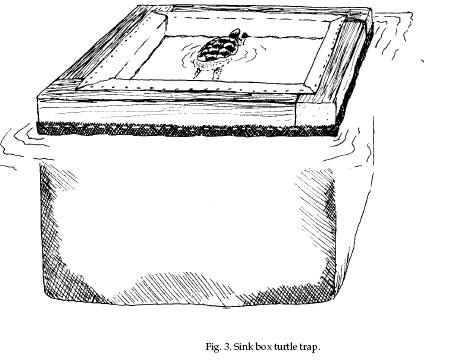

By

takingadvantage of this fact, these basking species may

be taken by trapping in a box sunk in a place the

turtles are using. The turtles crawl up onto the top of

the box to bask in the sun, and many of them fall into

the trap (Fig. 3). By

takingadvantage of this fact, these basking species may

be taken by trapping in a box sunk in a place the

turtles are using. The turtles crawl up onto the top of

the box to bask in the sun, and many of them fall into

the trap (Fig. 3).

The top frame of the box

may be constructed from discarded telephone poles,

imperfect ties, or logs about 8 inches (20 cm) in

diameter. Old natural unpainted wood is preferred. The

logs are mitered at each end to fit together, and the

inside enclosure made to measure 2 to 3 feet (61 to 91

cm) square. About half of each log from the top center

to the inside under center is lined with zinc or

galvanized metal. Turtles that have dropped into the

trap are unable to climb over the zinc or galvanized

metal covering. From the outside water edge to the top

of each

log,

cleats can be nailed or the logs made rough, so turtles

can easily climb on top. Galvanized mesh wire can be

fastened to the logs with staples, hooks, or wire to

form a wire basket fitting the opening between the logs.

One-inch (2.5-cm) mesh is about right if all sizes of

turtles are to be trapped. If only larger specimens are

sought, however, a 3-inch (7.6-cm) mesh can be used. The

trap should be fastened to a stump or some other

permanent anchor. log,

cleats can be nailed or the logs made rough, so turtles

can easily climb on top. Galvanized mesh wire can be

fastened to the logs with staples, hooks, or wire to

form a wire basket fitting the opening between the logs.

One-inch (2.5-cm) mesh is about right if all sizes of

turtles are to be trapped. If only larger specimens are

sought, however, a 3-inch (7.6-cm) mesh can be used. The

trap should be fastened to a stump or some other

permanent anchor.

Some trappers prefer to

use bait; others leave the traps unbaited. For the

capture of snapping and soft-shelled turtles, the trap

can be modified by installing funnel-like entrances on

one or two sides as described for the hoop traps.

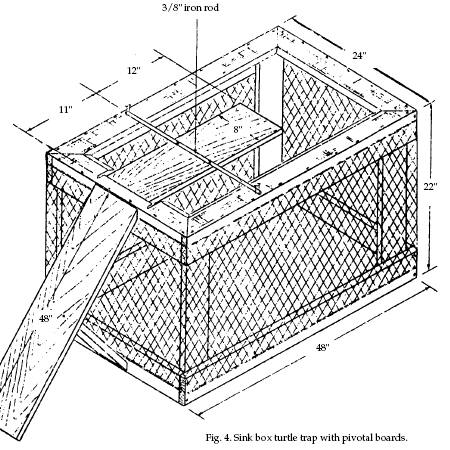

Another type of trap

consists of a box with an inclined board leading up to

it. The turtles climb up on the board to bask and drop

off into the box. Figure 4 shows the same trap with

pivotal boards placed so that turtles crawling out on

the boards overbalance on the terminal end and are

dropped into the box.

Shooting

In some states, shooting

can also be used as a means of reducing populations in

ponds and lakes. This technique, however, is not very

effective.

Economics of Damage and Control

Three groups of turtles

are of economic importance in North America. They

include the snapping turtles; the box, pond, and marsh

turtles; and the soft-shelled turtles. Snapping turtles

are trapped for human consumption and are being

considered for aquaculture. Red-eared turtles are

cultured for the foreign pet trade. Soft-shell turtles

are also trapped for human consumption.

Damage is typically of

little economic concern, but may be a problem in rice

and aquacultural production.

Acknowledgments

Figure 1 from C. W.

Schwartz: Wildlife Drawings (1980), Missouri Department

of Conservation, Jefferson City.

Figures 2 through 4 from

Wildlife Damage Control Handbook (1969), Kansas State

University, Manhattan. Adapted by Emily Oseas Routman.

For Additional Information

Conant, R., and J. T. Collins. 1991. A field guide to

reptiles and amphibians: eastern and central North

America. 3d ed. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston. 450 pp.

Ernst, C. H., and R. W.

Barbour. 1972. Turtles of the United States. Univ.

Kentucky Press, Lexington. 347 pp.

Stebbens, R. L. 1985. A

field guide to western reptiles and amphibians. 2d ed.

Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. 279 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

01/26/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|