|

|

|

|

|

REPTILES, AMPHIBIANS, ETC: Rattlesnakes |

|

|

Fig. 1. Prairie

rattlesnake, Crotalus viridis viridis

Introduction

Introduction Rattlesnakes

are distinctly American serpents. They all have a

jointed rattle at the tip of the tail, except for one

rare species on an island off the Mexican coast.

This chapter concerns the

genus Crotalus, of the pit viper family Crotalidae,

suborder Serpentes. Since snakes evolved from lizards,

both groups make up the order Squamata.

This article describes the

characteristics of the common species of rattlesnakes

that belong to the genus Crotalus. These include the

eastern diamondback, (C. adamanteus); the western

diamond (back) rattlesnake, (C. atrox); the red diamond

rattlesnake, (C. ruber); the Mohave rattlesnake, (C.

scutulatus); the sidewinder, (C. ceraster); timber

rattlesnake, (C. horridus); three subspecies of the

western rattlesnake, (C. viridis): the prairie

rattlesnake (C. v. viridis); the Great Basin rattlesnake

(C. v. lutosus); and the Pacific rattlesnake (C. v.

oreganus).

*Information pertains to

other poisonous snakes.

There are 15 species of

rattlesnakes in the United States and 25 in Mexico.

Other front-fanged poisonous snakes of the Crotalidae

family, which are not included in this discussion, are

the massasauga and pigmy rattlesnakes, both of the genus

Sistrurus. Also not included are two snakes that do not

have rattles, hence are not called rattlesnakes: the

water moccasin or cottonmouth, and the copperhead, both

of the genus Agkistrodon. Two other genera of poisonous

snakes in North America are coral snakes (Micrurus and

Micruroides) of the family Elapidae.

Identification

Rattlesnakes are usually

identified by their warning rattle — a hiss or buzz —

made by the rattles at the tip of their tails. A

rattlesnake is born with a button, or rattler, and

acquires a new rattle section each time it molts.

Rattlesnakes also are distinguished by having rather

flattened, triangular heads. The heads of all Crotalus

rattlesnakes are about twice as wide as their necks.

Only pit vipers possess this head configuration; coral

snakes do not.

Rattlesnakes belong to the

pit viper family Crotalidae, so named because all

possess visible loreal pits, or lateral heat sensory

organs, between eye and nostril on each side of the head

(Fig. 2). These heat sensory pits are not present in

true vipers, which do not occur in the Western

Hemisphere. The facial pits enable rattlesnakes to seek

out and strike, even in darkness, warm objects such as

small animal prey, as well as larger animals that could

be a threat. The vertically elliptical eye pupils, or

“cat eyes,” are also a characteristic of rattlesnakes

(Fig. 2). Identifying a dead rattler whose rattles are

missing can be done by looking at the snake’s scales on

the underside in the short region between the vent and

the tip of the tail. If the scales are divided down the

center, the snake is harmless. The scales on

rattlesnakes are not divided.

Rattlesnakes come in a

great variety of colors, depending on the species and

stage of molt. Most rattlers are various shades of

brown, tan, yellow, gray, black, chalky white, dull red,

and olive green. Many have diamond, chevron, or blotched

markings on their backs and sides.

Elliptical eye pupil

Fig. 2. Rattlesnake head

showing “cat-eye” elliptical pupil and location of the

large loreal pit, characteristic of pit vipers.

Range and Habitat

Rattlesnakes occur only in

North and South America and range from sea level to

perhaps 11,000 feet (over 3,000 m) in California and

14,000 feet (4,000 m) in Mexico, although they are not

abundant at the higher elevations. They are found

throughout the Great Plains region and most of the

United States, from deserts to dense forests and from

sea level to fairly high mountains. They need good cover

so they can retreat from the sun. Rattlers are common in

rough terrain and wherever rodents are abundant.

Food Habits

Young or small species of

rodents comprise the bulk of the food supply for most

rattlesnakes. Larger rattlers may capture and consume

squirrels, prairie dogs, wood rats, cottontails, and

young jackrabbits. Occasionally, even small carnivores

like weasels and skunks are taken. Ground-nesting birds

and bird eggs can also make up an appreciable amount of

the diet of some rattlers. Lizards are frequently taken

by rattlers, especially in the Southwest. The smaller

species of rattlesnakes and young rattlesnakes regularly

feed on lizards and amphibians.

Rattlesnakes consume about

40% of their own body weight each year. Many prey are

killed but not eaten by rattlesnakes because they are

too large or cannot be tracked after being struck. One

male rattler captured in the field had consumed 123% of

its weight, but young rattlers frequently die due to

lack of food. Domestically raised rattlesnakes will

survive when fed only once a year, but in the field,

snakes usually feed more than once, depending on the

size of prey consumed. A snake may kill several prey,

one after another, and of different species. When

rodents and rabbits are struck, the prey is immediately

released. The snake then uses its tongue to track the

prey to where it has died.

Digestion is quite slow

and usually no bones remain in the feces, called

“scats.” Hair, feathers, and sometimes teeth, however,

can usually be identified in scats. Rattlesnakes use

very little energy except when active, and they probably

are active for less than 10% of their lives. They are

not very active unless food is scarce. They store much

fat in their bodies, which can last them for long

periods.

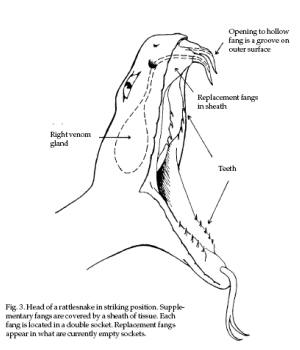

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

When a rattlesnake strikes

its prey or enemy, the paired fangs unfold from the roof

of its mouth. Prior to the completion of the forward

strike motion, the fangs become fully erect at the outer

tip of the upper jaw. The erectile fangs are hollow and

work like hypodermic needles to inject a modified

saliva, the venom, into the prey. Rattlesnakes can

regulate the amount of venom they inject when they

strike.

Mature fangs generally are

shed several times a season. They may become embedded in

the prey and may even be swallowed with the prey. When

one mature fang in a pair is lost, it will soon be

replaced by another functional mature fang. A series of

developing fangs are located directly behind one another

in the same sheath at the roof and outer tip of the

mouth (Fig. 3). If a newly replaced fang is artificially

removed, it may require weeks or longer before another

replacement will be fully effective. One fang can

function, however, while the other in the pair is being

replaced. Fangs that get stuck in a person’s boot are

not very dangerous; they cannot contain much venom since

they serve only as a hollow needle. The external opening

of the hollow fang is a groove on the outside of the

fang, set slightly back from the tip to prevent it from

becoming plugged by tissue from the prey (Fig. 3).

Rattlesnakes cannot spit

venom, but the impact of a strike against an object can

squeeze the venom gland, located in the roof of the

mouth, and venom may be squirted. This can happen when a

rattler strikes the end of a stick pointed at it, or the

wire mesh of a snake trap. The venom is released

involuntarily if sufficient pressure is exerted, as

occurs when venom is artificially “milked” from live

snakes. Such venom is dangerous only if it gets into an

open wound. Always wear protective clothing when

handling rattlesnakes.

Female rattlesnakes are

ovoviviparous. That is, they produce eggs that are

retained, grow, and hatch internally. The young of most

species of rattlesnakes are 6 to 8 inches (15 to 20 cm)

when born. They are born with a single rattle or button,

fangs, and venom. They can strike within minutes, but

being so small, they are not very dangerous. Average

broods consist of 5 to 12 young, but sometimes twice as

many may be produced.

The

breeding season lasts about 2 months in the spring when

the snakes emerge from hibernation. Sperm is thought to

survive in the female as long as a year. During summer,

pregnant females usually do not feed, so few are ever

captured that contain eggs about to hatch. The young are

born in the fall. Most rattlesnakes are mature in 3

years, but may require more time in northerly areas.

Rattlesnakes may not produce young every year. The

breeding season lasts about 2 months in the spring when

the snakes emerge from hibernation. Sperm is thought to

survive in the female as long as a year. During summer,

pregnant females usually do not feed, so few are ever

captured that contain eggs about to hatch. The young are

born in the fall. Most rattlesnakes are mature in 3

years, but may require more time in northerly areas.

Rattlesnakes may not produce young every year.

The sex of a rattlesnake

is not easy to determine. Even though the tail of the

rattlesnake (the distance between the vent and the

rattles) is quite short, it is much longer in males than

in females of the same size. The paired hemipenises of

male snakes are not visible except during mating, when

one of these paired hollow organs is turned inside out

and extruded from the cloaca. If both are extruded

artificially, they appear like two forked, stumpy legs.

Snakes never close their

eyes, since they have no eyelids. They are deaf, but can

detect vibrations. They have a good sense of smell and

vision, and their forked tongues transport microscopic

particles from the environment to sensory cells in pits

at the roof of the mouth. A rattlesnake uses these pits

to track prey it has struck and to gather information

about its environment.

Snakes have a large number

of ribs and vertebrae with ball-and-socket joints. Each

rib is joined to one of the scales on the snake’s

underside. The snake accomplishes its smooth flowing

glide by hooking the ground with its scales, which are

then given a backward push from the ribs. Rattlesnakes

often look much larger when seen live than after they

have been killed. This happens because their right lung

extends almost the full length of the tubular body, and

when the snakes inhale they can appear much fatter and

more threatening. The expulsion of the air can produce a

hiss.

Rattlesnakes, like other

snakes, periodically shed their skin. When the new skin

underneath is formed, the snake rubs its snout against a

stone, twig, or rough surface until a hole is worn

through. After it works its head free, the snake

contracts its muscles rhythmically, pushing, pulling,

and rubbing, until it can crawl out of the old skin,

which peels off like an inverted stocking. Each molt

produces a new rattle. Some rattles usually break off

from older snakes. Even if no rattles have been lost,

they do not indicate exact age because several rattles

may be produced in one season.

Even though the optimum

temperature for rattlesnakes is around 77o to 89o F (25o

to 32o C), the greatest period of activity is spring,

when they come out of hibernation and are seeking food.

If lizards are active, be alert for rattlesnakes. The

activity period for rattlers can vary from about 10

months or so in warm southern regions to perhaps less

than 5 months in the north and at high elevations.

Depending upon availability of good, dry denning sites

below the frost line, rattlesnakes may hibernate alone

or in small numbers. However, sometimes they den in

large groups of several hundred in abandoned prairie dog

burrows or rock caverns, where they lie torpid in groups

or “balls.” All dens must be deep enough so the

temperature is not affected by occasional warm days. If

not, the snakes might emerge too early in spring only to

become sluggish and vulnerable should the weather again

turn cold. Since snakes are cold-blooded animals and

their body temperature is altered by air temperature,

refrigeration makes them sluggish and easy to handle for

displaying.

Rattlesnakes usually see

humans before humans see them, or they detect soil

vibrations made by walking. They coil for protection,

but they can strike only from a third to a half of their

body length. Rattlers rely on surprise to strike prey.

Once a prey has been struck, but not killed, it is

unlikely that it will be struck again. Experienced

rodents and dogs can evade rattlesnake strikes.

Rattlesnakes may appear

quite aggressive if exposed to warm sunshine. Since they

have no effective cooling mechanism, they may die from

heat stroke if kept in the sun on a hot day much longer

than 15 or 20 minutes.

If a rattlesnake has just

been killed by cutting off its head, it can still bare

its fangs and bite. The heat sensory pits will still be

functioning, and the warmth of a hand will activate the

striking reflex. The head cannot strike, but it can bite

and inflict venom. The reflex no longer exists after a

few minutes, or as long as an hour or more if it is

cool, as rigor mortis sets in.

Damage and Damage Identification

The greatest danger to

humans from rattlesnakes is that small children may be

struck while rolling and tumbling in the grass. Only

about 1,000 people are bitten and less than a dozen

people die from rattlesnake venom each year in the

United States. Nevertheless, it is a most unpleasant

experience to be struck. The venom, a toxic enzyme

synthesized in the snake’s venom glands, causes tissue

damage, as it tends to quickly tenderize its prey. When

known to be abundant, rattlesnakes detract from the

enjoyment of outdoor activities. The human fear of

rattlesnakes is much greater than the hazard, however,

and many harmless snakes inadvertently get killed as a

result. Death from a rattlesnake bite is rare and the

chance of being bitten in the field is extremely small.

Experienced livestock

operators and farmers usually can identify rattlesnake

bites on people or on livestock without much difficulty,

even if they did not witness the strike. A rattlesnake

bite results in almost immediate swelling, darkening of

tissue to a dark blue-black color, a tingling sensation,

and nausea. Bites will also reveal two fang marks in

addition to other teeth marks (all snakes have teeth;

only pit vipers have fangs too). Rattlesnakes often bite

livestock on the nose or head as the animals attempt to

investigate them. Sheep, in particular, may crowd

together in shaded areas near water during midday. As a

consequence, they also frequently are bitten on the legs

or lower body when pushed close to snakes. Fang marks

and tissue discoloration that follows in the major blood

vessels from the bite area are usually apparent on

livestock that are bitten (see Wade and Bowns 1982,

pages 32 and 34 in the Damage Identification section of

this book).

Legal Status

Most species of

rattlesnakes are not considered threatened or

endangered. Since they are potentially dangerous, there

has not been much support for protecting them except in

national parks and preserves. However, since there are

state and local restrictions, contact local wildlife

agencies for more information.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

An occasional single

poisonous snake can be destroyed if one has enough

determination. In areas where the habitat is favorable

for rattlesnakes, copperheads, or water moccasins, a

significant reduction in their population density may be

difficult. In snake country, most people learn to “keep

their eyes open” and be cautious.

Exclusion

When feasible, the most

effective way for a homeowner to protect a child’s play

area from rattlesnakes is to construct a

rattlesnake-proof fence around it. The fencing must be

tight. If wire mesh is used, it should be 1/4-inch

(0.6-cm) mesh and about 3 feet (1 m) high. Bury the

bottom 3 or 4 inches (8 or 10 cm) or bend outward 3 or

more inches of the base of the wire to discourage other

animals from digging under the fence. Put the stakes on

the inside and install a gate that is tight-fitting at

the sides and bottom, equipped with a self-closing

spring. The benefit of the fence will be lost if wood,

junk, or thick vegetation accumulates against the

outside of the fence. Vegetation that has ground-level

foliage also provides attractive hiding places for

rattlesnakes, so it should be removed or properly

pruned. Tight-fitting doors will prevent snakes from

entering outbuildings. The foundations of all buildings

should be sealed or tightly screened with 1/4-inch

(0.6-cm) wire mesh to keep out snakes.

Habitat Modification

It is always desirable to

use nonlethal biological means of control when feasible.

Although good quantified data are not available to

evaluate the effectiveness of removing the prey of

snakes, effective, sustained rodent control will reduce

the attractiveness of a rural residence or other

facility to rattlesnakes. Snakes will not remain in

habitat made less favorable for them. Hiding places

under buildings, piles of debris, or dense vegetation

should be removed. Hay barns and feed storage areas that

encourage rodents will attract rattlers.

Frightening

No methods are known that will frighten

rattlesnakes. Sounds certainly will not work because

snakes are deaf.

Repellents

Many potential snake

repellents have been researched, only to be found

ineffective. All species of snakes are likely to cross a

strip of repellent substance if they want to get to the

other side. Dr. T’s Snake-A-Way®, a mixture of sulphur-naphthalene,

has been registered by EPA; however, its registration in

California was denied as of July 1991, because required

data was not submitted. A Y-shaped laboratory enclosure

that provided rattlers with a choice of crawling into a

tunnel with odor or one free of odor showed they usually

chose the passage free of odor. No field test data is

available. To be of practical use, the odor of a snake

repellent must not be too objectionable to people.

Toxicants No effective

toxicant is registered for the control of rattlesnakes.

When rodents were poisoned with various rodenticides and

then fed to rattlesnakes, the snakes were not affected.

Apparently, digestion is too slow for the toxicants to

have an effect on snakes.

Fumigants

It may be possible to kill

rattlesnakes in burrows and rock dens with toxic gas,

although this is not a very practical method. Calcium

cyanide is a chemical frequently recommended, but no

lethal gas has had good success because snakes have such

a slow rate of metabolism, especially when in

hibernation. In addition, susceptible nontarget species

in the burrows or dens may become victims. In the spring

and early summer, when hibernating snakes are about to

emerge, gasoline poured down a burrow or into a den will

drive the snakes out. As the snakes exit they can be

clubbed, shot, or captured alive with snake tongs that

secure a snake at its neck. If transported in a bag, tie

the top securely. Many snake hunters push a hose down a

burrow and after listening to confirm that rattlesnakes

are present, pour 1 to 2 ounces (30 to 60 ml) of

gasoline into a funnel on the hose and then blow on the

hose. This technique seems quite effective for

seasonally reducing rattlesnake numbers, but it may be

lethal to nontarget animals including nonpoisonous and

beneficial snakes. To be effective, community- wide

campaigns should extend over several days, since many

snakes may escape into holes or crevices. Snake hunters

should wear protective clothing such as pants, heavy

gloves, and boots.

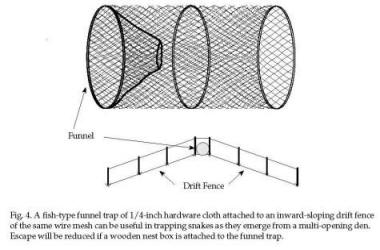

Trapping

Various combinations of

fencing and traps at known rattlesnake dens can be very

successful if one is trying to collect rattlesnakes,

because in some localities several hundred rattlesnakes

may occupy the same den. If all but one opening can be

blocked, it is then quite simple to pipe or otherwise

channel the emerging rattlesnakes into a large oil drum

or other receptacle. If it is not possible to find all

den openings, inward-sloping drift fences of 1/4-inch

(0.6-cm) hardware cloth mesh, 1 or 2 feet (0.5 m) high,

with fish-type funnel traps (Fig. 4) will suffice. The

inward sloping funnel makes it difficult for the snakes

to escape. If a wooden nestbox is attached to one side

of these traps, the snakes will usually hide in the box

and not spend as much time trying to escape. Drift-fence

funnel traps also catch many other animals. Therefore,

this control method requires daily inspection and

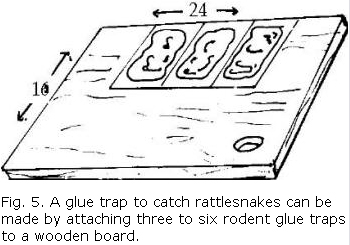

usually is not very practical except at dens. Glue

boards are useful for trapping rattlesnakes that are in

or under buildings (Knight 1986). To trap rattlesnakes,

use a plywood board approximately 24 x 16 inches (61 x

41 cm). Securely tack a 6 x 12-inch (15 x 30-cm) rodent

glue trap (or use bulk glue to make a similar-sized glue

patch) to the plywood (Fig. 5). Place the board against

a wall, as this is where snakes are likely to travel.

The rattlesnake will become stuck while attempting to

cross the board. Do not place the board near any objects

(pipes, beams) that the snake can use for leverage in

attempting to free itself.

Fig. 5. A glue trap to

catch rattlesnakes can be made by attaching three to six

rodent glue traps to a wooden board.

The glue trap can be

removed easily using a long stick or pole with a hook or

by an attached rope if a hole is drilled through the

plywood board. Animals trapped in the glue can be

removed with the aid of vegetable oil, which counteracts

the adhesive.

Do not use glue boards

outdoors or in any location where they are likely to

catch pets or desirable nontarget wildlife. The glue can

be quite messy and is difficult to remove from animals.

Shooting

A shotgun has often been

used to eliminate individual rattlesnakes around a rural

homestead. Similarly, a pistol loaded with birdshot is

very effective at close range. Shooting is not

considered effective for reducing large populations.

Other Methods

Dynamite blasting of known

dens is dangerous and has questionable advantages. There

is no way to know what kinds and how many snakes have

been killed, and the blast may create an even better den

for future rattlesnakes.

Rattlesnakes have natural

predators, but the predators are not likely to help much

in controlling rattlesnake populations. Some dogs,

especially if they have experienced a snake bite, become

excellent guards for children. They will bark when a

snake is discovered, and many can kill rattlesnakes as

well. Domestic geese and turkeys may also help, by

acting as an alarm and by frightening snakes. Hogs do

not provide practical protection around a homestead.

Snake Bite

The best protection for

humans when traveling in snake country is common sense

in choosing protective foot and leg wear. When climbing,

one should beware of putting a hand up over rocks.

Rattlesnakes might be waiting there for a rodent, and

the warmth in a hand may cause the snake to strike

reflexively. Care should be taken at night, when snakes

are more active, and the chance of stepping on a snake

is greater. Fortunately, rattlesnakes try to avoid

people.

The best first aid for a

poisonous snake bite is to seek immediate medical care

and to keep the victim calm, warm, and reassured. Do not

drink alcohol or use ice, cold packs, or freon spray to

treat the snake bite or cut the wound, as was once

recommended.

If a victim of snake bite

is several hours from a car and medical aid, apply a

light constricting cloth or other band on the bitten

limb, 2 to 4 inches(5 to 10 cm) from the bite and

between bite and heart. Make sure it is not as tight as

a tourniquet. It should be easy to insert a finger under

the band. Loosen it if swelling occurs. Apply suction at

the wound for at least 3/4 of an hour by mouth (if no

mouth sores), or with a snake bite kit, but again, only

if medical assistance is several hours away.

The causes of human death

from rattlesnake venom are varied, but usually occur

from extended hypotension and cardiopulmonary arrest.

Usually within a few minutes after being struck the

victim will experience pain and swelling at the wound

site.

Economics of Damage and Control

The greatest economic loss

to humans from rattlesnakes comes from the number of

domestic livestock and pets that are killed. Horses and

cattle are most frequently struck in the head while

grazing. Some have claimed that rattlesnakes benefit

ranchers by the number of rodents they eat, but current

predator-prey theory discounts this. It is very doubtful

that snakes have much effect on the density of rodents.

The commercial value of

rattlesnakes consists of the venom, rattles, skins and,

to a limited degree, the meat.

Acknowledgments

Figures 1 through 3 by

Emily Oseas Routman.

Figures 4 and 5 by Jill

Sack Johnson.

For Additional Information

Dunkle, T. 1981. A perfect

serpent. Science 81 2:30-35.

Duvall, D., M. B. King,

and K. J. Gutzwiller. 1985. Behavioral ecology and

ethology of the prairie rattlesnake. Natl. Geogr. Res.

1:80-111.

Dolbeer, R. A., N. R.

Holler, and D. W. Hawthorne. 1994. Identification and

control of wildlife damage. Pages 474-506 in T. A.

Bookhout ed. Research and management techniques for

wildlife and habitats. The Wildl. Soc. Bethesda,

Maryland.

Kilmon, J., and H.

Shelton. 1981. Rattlesnakes in America. Shelton Press,

Sweetwater, Texas. 234 pp.

Klauber, L. M. 1972.

Rattlesnakes: their habits, life histories, and

influence on mankind, 2 vols. Univ. California Press,

Berkeley. 1533 pp.

Klauber, L. M. 1982.

Rattlesnakes: their habitats, life histories, and

influence on mankind. Abridged by K. H. McClung. Univ.

California Press, Berkeley. 350 pp.

Knight, J. E. 1986. A

humane method for removing snakes from dwellings. Wildl.

Soc. Bull. 14:301-303.

Marsh, R. E., and W. E.

Howard. 1982. Vertebrate pests. Pages 791-861 in A.

Maillis, ed. Handbook of pest control, 6th ed. Franzak

and Foster Co., Cleveland, Ohio. 1001 pp.

Pinney, R. 1981. The snake

book. Doubleday & Co., New York. 248 pp.

San Julian, G. J., and D.

K. Woodward. 1986. What you wanted to know about all you

ever heard concerning snake repellents. Proc. Eastern

Wildl. Damage Control Conf. 2:243-248.

Seigle, R. A., J. T.

Collins, and S. S. Novak. 1987. Snakes: ecology and

evolutionary biology. Macmillan Publ. Co., New York. 529

pp.

Story, K. 1987. Snakes:

separating fact from fantasy. Pest Control Technol.

15(11):54,55,58,60.

Wade, D. A., and J. E.

Bowns. 1982. Procedures for evaluating predation on

livestock and wildlife. Bull. No. B-1429, Texas A & M

Univ., College Station. 42 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committe

01/26/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|