|

|

|

|

|

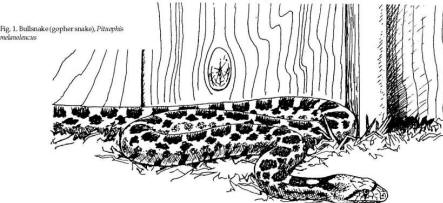

REPTILES, AMPHIBIANS, ETC: Nonpoisonous

Snakes |

|

|

Identification

Of the many kinds of

snakes found in the United States, only the following

are harmful: rattlesnakes, copperheads, cottonmouths,

coral snakes, and sea snakes. The latter group lives

only in the oceans. All poisonous snakes, except coral

snakes and sea snakes, belong in a group called pit

vipers. There are three ways to distinguish between pit

vipers and nonpoisonous snakes in the United States:

(1) Allpit vipers have a

deep pit on each side of the head, midway between the

eye and the nostril. Nonpoisonous snakes do not have

these pits.

(2) On the underside of

the tail of pit vipers, scales go all the way across in

one row (except on the very tip of the tail, which may

have two rows in some cases). On the underside of the

tail of all nonpoisonous snakes, scales are in two rows

all the way from the vent of the snake to the tip of the

tail (Fig. 2). The shed skin of a snake shows the same

characteristics.

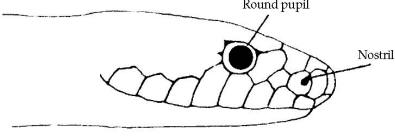

(3) The pupil of pit

vipers is vertically elliptical (egg-shaped). In very

bright light, the pupil may be almost a vertical line,

due to extreme contraction to shut out light. The pupil

of nonpoisonous snakes is perfectly round (Fig. 3).

The poisonous coral snake

is ringed with red, yellow, and black, with red and

yellow rings touching. Nonpoisonous mimics of the coral

snake (such as the scarlet king snake) have red and

yellow rings, separated by black rings. A helpful saying

to memorize is: “Red on yellow, kill a fellow; red on

black, friend of Jack.”

Range

Some species of

nonpoisonous snakes occur throughout several states, but

the majority have only limited ranges.

Fig. 3. Nonpoisonous

snakes have a round eye pupil and have no pit between

the eye and the nostril.

Habitat

Snakes are not very

mobile, and even though some are fairly adaptable, most

have specific habitat requirements. Some live

underground (these are mostly small in size), and some

have eyes shielded by scales of the head. Others, such

as green snakes, live primarily in trees. One group

spends its entire life in the oceans. In general, snakes

like cool, damp, dark areas where they can find food.

The following are areas around the home that seem to be

attractive to snakes: firewood stacked directly on the

ground; old lumber piles; junk piles; flower beds with

heavy mulch; gardens; unkempt basements; shrubbery

growing against foundations; barn lofts— especially

where stored feed attracts rodents; attics in houses

where there is a rodent or bat problem; stream banks;

pond banks where there are boards, innertubes, tires,

planks, and other items lying on the bank; unmowed

lawns; and abandoned lots and fields.

Food Habits

All snakes are predators,

and the different species eat many different kinds of

food. Rat snakes eat primarily rodents (such as rats,

mice, and chipmunks), bird eggs, and baby birds. King

snakes eat other snakes, as well as rodents, young

birds, and bird eggs. Some snakes, such as green snakes,

eat primarily insects. Some small snakes, such as earth

snakes and worm snakes, eat earthworms, slugs, and

salamanders. Water snakes eat primarily frogs, fish, and

tadpoles.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Snakes are specialized

animals, having elongated bodies and no legs. They have

no ears, externally or internally, and no eyelids,

except for a protective window beneath which the eye

moves. The organs of the body are elongated. Snakes have

a long, forked tongue, which helps them smell. Gaseous

particles from odors are picked up by the tongue and

inserted into the two-holed organ, called the Jacobson’s

Organ, at the roof of the mouth.

The two halves of the

lower jaw are not fused, but are connected by a ligament

to each other. They are also loosely connected so the

snake can swallow food much larger than its head.

Because snakes are cold-blooded and not very active, one

meal may last them several weeks. Also, because they are

cold-blooded, they may hibernate during cold weather

months or aestivate during hot summer months when the

climate is severe. In either case, they consume little

or no food during these times. Some snakes lay eggs,

some hatch their eggs inside the body, and some give

live birth. The young of copperheads, rattlesnakes, and

cottonmouths are born alive.

Nonpoisonous snakes are

harmless to humans. In most cases, a snake will crawl

away when approached if it feels it can reach cover

safely. No snakes charge or attack people, with the

exception of the racers, which occasionally bluff by

advancing toward an intruder. Racers will retreat

rapidly, however, if challenged. Snakes react only when

cornered. Different species react in different ways,

playing dead by turning over on the back, hissing,

opening the mouth in a menacing manner, coiling, and

striking and biting if necessary.

Damage and Damage Identification

A nonpoisonous snake bite

has no venom and can do no more harm than frighten the

victim. After being bitten several thousand times by

nonpoisonous snakes, the author and his students have

never suffered any adverse reaction, and no treatment

was ever used. The only harm nonpoisonous snakes can

cause is frightening people who are not familiar with

them. A bite from a poisonous snake, however, causes an

almost immediate reaction—swelling, tissue turning a

dark blue-black, a tingling sensation, and nausea. If

none of these is observed or felt, the bite was from a

nonpoisonous snake. Also, bites from one of the pit

vipers (copperheads, rattlesnakes, and cottonmouths)

will reveal two fang marks, in addition to teeth marks.

All snakes have teeth; only pit vipers have fangs. North

American pit vipers have only two rows of teeth on top

and two on the bottom, whereas nonpoisonous snakes have

four on top and four on the bottom.

Legal Status

In most states, snakes are

considered nongame wildlife and are protected by state

law unless they are about to cause personal or property

damage. Therefore, snakes should not be indiscriminately

killed. Some species are listed on federal and/or state

threatened and endangered species lists.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Snakes enter houses, barns

and other buildings when habitat conditions are suitable

inside the buildings. They are particularly attracted to

rodents and insects as well as cool, damp, dark areas

often associated with buildings. All openings 1/4 inch

(0.6 cm) and larger should be sealed to exclude snakes.

Check the corners of doors and windows, as well as

around water pipe and electrical service entrances.

Holes in masonry foundations (poured concrete and

concrete blocks or bricks) should be sealed with mortar

to exclude snakes. Holes in wooden buildings can be

sealed with fine mesh (1/8-inch [0.3-cm]) hardware cloth

or sheet metal.

In some cases, the

homeowner may get peace of mind by constructing a

snake-proof fence around the home or yard (Fig. 4). A

properly constructed snake-proof fence will keep out all

poisonous snakes and most harmless snakes (some

nonpoisonous snakes are fairly good climbers). The cost

of fencing a whole yard may be high, but it costs little

to enclose a play space for children too young to

recognize dangerous snakes. The following design is

taken from information from the US Fish and Wildlife

Service.

The fence should be made

of heavy galvanized hardware cloth, 36 inches (91 cm)

wide with a 1/4-inch (0.6-cm) mesh. The lower edge

should be buried 6 inches (15 cm) in the ground, and the

fence should be slanted outward from the bottom to the

top at a 30o angle (Fig. 5). Place supporting stakes

inside the fence and make sure that any gate is tightly

fitted. Gates should swing inward because of the outward

slope of the fence. A 36-inch (91-cm) vertical fence

with a 12-inch (30-cm) lip at the top, facing outside

and angled downward at a 30o angle would probably work

as well.

Any opening under the

fence should be firmly filled—concrete is preferable.

Mow all vegetation just outside the fence, for snakes

might use these plants to help climb over the fence. If

children tend to crush the fence, it must be supported

by more and sturdier stakes and by strong wire connected

to its upper edge.

Habitat Modification

The primary food of most

snakes, especially the larger ones, is birds, bird eggs,

and rodents such as rats, mice, and chipmunks. No

control program for rodent-eating snakes is ever

complete without removing rodents and rodent habitats.

Put all possible sources of rodent food in secure

containers. Be sure to keep all dog or cat food cleaned

up after each feeding and make the stored food

unavailable to the rodents. Keep all vegetation closely

mowed around buildings. Remove bushes, shrubs, rocks,

boards, and debris of any kind lying close to the

ground, as these provide cover for both rodents and

snakes. Refer to the chapters on rodents for more

information on their control.

Frightening

Not applicable.

Repellents

Several repellents have

been used in the past, but none has been consistently

effective. Currently Dr. T’sTM Snake-A-Way® is

registered for the control of rattlesnakes and the

checkered garter snake, but is apparently not effective

against most species of snakes. Active ingredients

include sulfur and naphthalene. Band applications around

the area to be protected are recommended.

Fumigants

There are no legal

fumigants to kill snakes. Moreover, because most snakes

do not burrow, using fumigants in underground burrows is

not a feasible method of control. In the past, pest

control operators have completely encased houses with

plastic and fumigated at tremendous expense to the

homeowner (several thousand dollars). This is not a

reasonable control method for nonpoisonous snakes since

the animals being killed are completely harmless.

Trapping Trapping

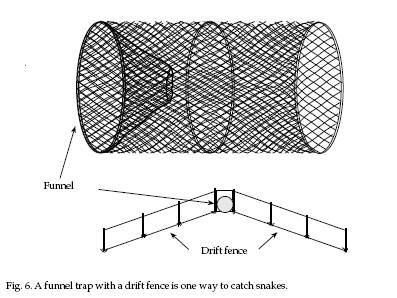

One method reported by

researchers to catch snakes involves a funnel trap with

drift fences constructed of 1/4- inch or 1/2-inch (0.6-

or 1.3-cm) mesh hardware cloth erected 2 feet (0.6 m)

high and 25 feet (7.5 m) long. Posts for drift fences

should be on the back side of the fence. These fences

guide animals into the funnel end of the trap (Fig. 6).

One type of funnel trap

can be made by rolling a 3 x 4-foot (0.9 x 1.2-m) piece

of 1/4-inch (0.6-cm) mesh hardware cloth into a cylinder

about 1 foot (0.3 m) in diameter and 4 feet (1.2 m)

long. An entrance funnel can be made similarly a

cylinder with hardware cloth and attach the drift fence.

To catch the animal from either direction, put another

funnel at the other end of the trap and another drift

fence facing the opposite direction.

Shooting

Nonpoisonous snakes are

protected by law in most states, and indiscriminate

killing is illegal. Shooting or clubbing is extremely

effective in states where it is allowed and will soon

eliminate the snake population. Permission may be

required from the local state wildlife agency.

Other Methods

It is not difficult to

remove snakes from inside a house or other buildings.

Place piles of damp burlap bags or towels in areas where

snakes have been seen or are likely to be found. Cover

each pile with a dry burlap bag or towel to slow

evaporation. Snakes are attracted to damp, cool, dark

areas such as these piles. After the bags or towels have

been out for a couple of weeks, completely remove them

with a large scoop shovel during the middle of the day

when snakes are likely to be inside or underneath.

Glue boards have proven to

be useful for trapping snakes in or under buildings.

Securely tack several rodent glue traps (or use bulk

glue) to a plywood board approximately 24 x 16 inches

(61 x 41 cm) to make a glue patch at least 7 x 12 inches

(15 to 30 cm). Place the board against a wall where

snakes are likely to travel. Snakes become stuck when

they try to cross the board. Do not place the board near

any object (pipes or beams) that the snake can use for

leverage in attempting to free itself. A hole drilled

through the plywood board will allow removal of the

board and the entrapped snake with a long stick or

hooked pole. Animals trapped in the glue can be removed

with the aid of vegetable oil, which counteracts the

adhesive.

Do not use glue boards

outdoors or in any location where they are likely to

catch pets or nontarget wildlife. The glue can be quite

messy and is hard to remove from animals.

Economics of Damage and Control

As mentioned earlier,

nonpoisonous snakes are completely harmless and cause no

damage, except occasionally frightening people.

Therefore, no expense toward control of nonpoisonous

snakes is justified. Most methods to remove snakes are

inexpensive, except for the snake-proof fence, which can

be quite expensive.

Acknowledgments

Appreciation is expressed

to the US Fish and Wildlife Service for some of the

information presented in this chapter, particularly the

design of the snake-proof fence.

Figures 1 through 3 by

Emily Oseas Routman.

Figures 4 through 6 by

Jill Sack Johnson.

For Additional Information

Boys, F. E. 1959.

Poisonous amphibians and reptiles. C. C. Thomas Co.,

Springfield, Illinois. 149 pp.

Conant,

R. 1975. A field guide to reptiles and amphibians of

eastern and central North America. Houghton Mifflin Co.,

Boston. 429 pp.

Ditmars,

R. L. 1939. A field book of North American snakes.

Doubleday, Doran, and Co., New York. 305 pp.

Ditmars,

R. L. 1966. Snakes of the world. Macmillan Co., New

York, 207 pp.

Huheey, J. E., and A.

Stupka. 1967. Amphibians and reptiles of the Great

Smokey Mountains National Park. Univ. Tennessee Press,

Knoxville. 98 pp.

Lamburn,

J. B. C. 1964. Snake lore. Doubleday and Co., New York.

152 pp.

Leviton,

A. E. 1971. Reptiles and amphibians of North America.

Doubleday and Co., New York. 250 pp.

Parker, H. W. 1977. Snakes

— a natural history. Cornell Univ. Press, 124 pp.

Schlauch,

F. C. 1976. City snakes, suburban salamanders. Nat. Hist.

85:46-53.

Schmidt, K. P., and D. D.

David. 1941. Field book of snakes of the United States

and Canada. G. P. Putnam’s Sons. New York. 365 pp.

Simon, H. 1973. Snakes:

the facts and the folklore. Viking Press, New York. 128

pp.

Stidworthy,

J. 1972. Snakes of the world. Bantam Books, Inc., 159

pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

01/26/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|