|

|

|

|

|

OTHER MAMMALS: Moles |

|

|

Identification

Yates and Pedersen (1982)

list seven North American species of moles. They are the

eastern mole (Scalopus aquaticus), hairy-tailed mole (Parascalops

breweri), star-nosed mole (Condylura cristata),

broad-footed mole (Scapanus latimanus), Townsend’s mole

(Scapanus townsendii), coast mole (Scapanus orarius) and

shrew mole (Neurotrichus gibbsii).

The mole discussed here is

usually referred to as the eastern mole (Scalopus

aquaticus). It is an insectivore, not a rodent, and

is related to shrews and bats.

True moles may be

distinguished from meadow mice (voles), shrews, or

pocket gophers—with which they are often confused—by

noting certain characteristics. They have a hairless,

pointed snout extending nearly 1/2 inch (1.3 cm) in

front of the mouth opening. The small eyes and the

opening of the ear canal are concealed in the fur; there

are no external ears. The forefeet are very large and

broad, with palms wider than they are long. The toes are

webbed to the base of the claws, which are broad and

depressed. The hind feet are small and narrow, with

slender, sharp claws.

Average Dimensions and

Weight

Males : Average

total length, 7 inches (17.6 cm) Average length of tail,

1 1/4 inches (3.3 cm) Average weight, 4 ounces (115 g)

Females: Average

total length, 6 5/8 inches (16.8 cm) Average length of

tail, 1 1/4 inches (3.3 cm) Average weight, 3 ounces (85

g).

Range

Fig.

2. Range of the eastern mole in North America. Fig.

2. Range of the eastern mole in North America.

Out of the seven species

that occur in North America, three inhabit lands east of

the Rocky Mountains (Yates and Pedersen 1982). The

eastern mole is the most common and its range is shown

in figure 2. The star-nosed mole is most common in

northeastern United States and southeastern Canada,

sharing much of the same range as the hairy-tailed mole.

The remaining four species are found west of the Rocky

Mountains. The Townsend mole and the coast mole are

distributed in the extreme northwest corner of the

United States and southwest Canada. The broad-footed

mole is found in southern Oregon and throughout the

coastal region of California excluding the Baja

peninsula. Finally, the shrew mole is also found along

the West Coast from Santa Cruz County, California, to

southern British Columbia (Yates and Pedersen 1982).

Habitat

The mole lives in the

seclusion of underground burrows, coming to the surface

only rarely, and then often by accident. Researchers

believe that the mole is a loner. On several occasions

two or even three moles have been trapped at the same

spot, but that does not necessarily mean they had been

living together in a particular burrow. Networks of

runways made independently occasionally join otherwise

separate burrows.

Because of their food

requirements, moles must cover a larger amount of area

than do most animals that live underground. The home

range of a male mole is thought to be almost 20 times

that of a male plains pocket gopher. Three to five moles

per acre (7 to 12 per ha) is considered a high

population for most areas in the Great Plains.

Deep runways lead from the

mole’s den to its hunting grounds. The denning area

proper consists of irregular chambers here and there

connected with the deep runways. The runways follow a

course from 5 to 8 inches (12.7 to 20.3 cm) beneath the

surface of the ground. The chambers from which these

runs radiate are about the size of a quart jar.

Most of a mole’s runway

system is made up of shallow tunnels ranging over its

hunting ground. These tunnels may not be used again or

they may be re-traversed at irregular intervals.

Eventually, they become filled by the settling soil,

especially after heavy showers. In some cases, moles

push soil they have excavated from their deep runways

into the shallow tunnels. These subterranean hunting

paths are about 1 1/4 to 1 1/2 inches (3.2 to 3.8 cm) in

diameter. Moles usually ridge up the surface of the

soil, so their tunnels can be readily followed. In wet

weather, runways are very shallow; during a dry period

they range somewhat deeper, following the course of

earthworms.

Moles make their home

burrows in high, dry spots, but they prefer to hunt in

soil that is shaded, cool, moist, and populated by worms

and grubs. This preference accounts for the mole’s

attraction to lawns and parks. In neglected orchards and

natural woodlands, moles work undisturbed. The ground

can be infiltrated with runways. Moles commonly make

their denning areas under portions of large trees,

buildings, or sidewalks.

The maze of passages that

thread the soil provides protective cover and traffic

for several species of small mammals. Voles (meadow

mice), white-footed mice, and house mice live in and

move through mole runways, helping themselves to grains,

seeds, and tubers. The mole, however, often gets blamed

for damaging these plants. Moles “swim” through soil,

often near the ground surface, in their search for

worms, insects, and other foods. In doing so, they may

damage plants by disrupting their roots (Fig. 3).

Food Habits

The teeth of a mole (see

Fig. 1) indicate the characteristics of its food and

general behavior. In several respects moles are much

more closely related to carnivorous or flesh-eating

mammals than to rodents. The mole’s diet consists mainly

of the insects, grubs, and worms it finds in the soil

(Table 1). Moles are thought to damage roots and tubers

by feeding on them, but rodents usually are to blame.

Moles eat from 70% to 100%

of their weight each day. A mole’s appetite seems to be

insatiable. Experiments with captive moles show that

they will usually eat voraciously as long as they are

supplied with food to their liking. The tremendous

amount of energy expended in plowing through soil

requires a correspondingly large amount of food to

supply that energy. Moles must have this food at

frequent intervals.

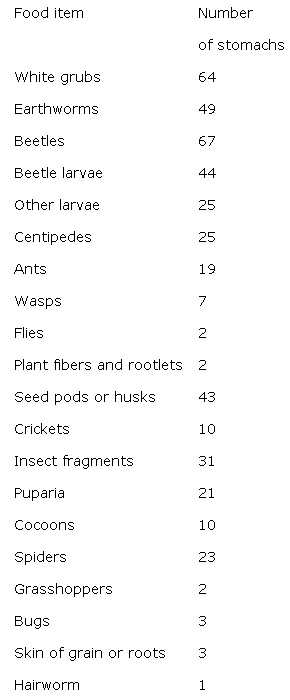

Table

1. Stomach contents of 100 eastern moles: Table

1. Stomach contents of 100 eastern moles:

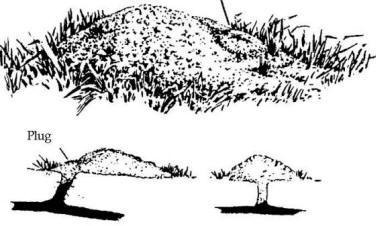

Fig.

3. Moles “swim” through soil, often near the ground

surface, in their search for worms, insects, and other

foods. In doing so, they may damage plants by disrupting

their roots. Fig.

3. Moles “swim” through soil, often near the ground

surface, in their search for worms, insects, and other

foods. In doing so, they may damage plants by disrupting

their roots.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Moles prefer loose, moist

soil abounding in grubs and earthworms. They are most

commonly found in fields and woods shaded by vegetation,

and are not able to maintain existence in hard, compact,

semiarid soil.

The mole is not a social

animal. Moles do not hibernate but are more or less

active at all seasons of the year. They are busiest

finding and storing foods during rainy periods in

summer.

The gestation period of

moles is approximately 42 days. Three to five young are

born, mainly in March and early April.

The moles have only a few

natural enemies because of their secluded life

underground. Coyotes, dogs, badgers, and skunks dig out

a few of them, and occasionally a cat, hawk, or owl

surprises one above ground. Spring floods are probably

the greatest danger facing adult moles and their young.

Damage

and Damage Identification

Moles remove many damaging

insects and grubs from lawns and gardens. However, their

burrowing habits disfigure lawns and parks, destroy

flower beds, tear up the roots of grasses, and create

havoc in small garden plots.

It is important to

properly identify the kind of animal causing damage

before setting out to control the damage. Moles and

pocket gophers are often found in the same location and

their damage is often confused. Control methods differ

for the two species.

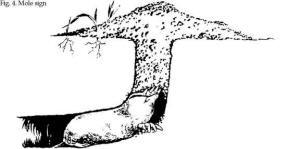

Moles leave volcano-shaped

hills (Fig. 4a) that are often made up of clods of soil.

The mole hills are pushed up from the deep tunnels and

may be 2 to 24 inches (5 to 60 cm) tall. The number of

mole hills is not a measure of the number of moles in a

given area. Surface tunnels (Fig. 4b) or ridges are

indicative of mole activity.

Pocket gopher mounds are

generally kidney-shaped and made of finely sifted and

cloddy soil (Fig. 4c). Generally, gophers leave larger

mounds than moles do. Gopher mounds are often built in a

line, indicative of a deeper tunnel system.

Legal Status

Moles are unprotected in

most states. See state and local laws for types of

traps, toxicants, and other methods of damage control

that can be used.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

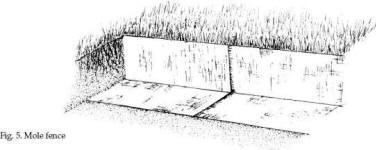

For small areas, such as

seed beds, install a 24-inch (61-cm) roll sheet metal or

hardware cloth fence. Place the fence at the ground

surface and bury it to a depth of at least 12 inches (30

cm), bent out at a 90o angle (Fig. 5).

Cultural Methods

In practice, packing the

soil with a roller or reducing soil moisture may reduce

a habitat’s attractiveness to moles. Packing may even

kill moles if done in the early morning or late evening.

Milky-spore disease is a

satisfactory natural control for certain white grubs,

one of the mole’s major food sources. It may take

several years, however, for the milky-spore disease to

become established. Treatments are most effective when

they are made on a community-wide basis. The spore dust

can be applied at a rate of 2 pounds per acre (2.3

kg/ha) and in spots 5 to 10 feet (1.5 to 3m) apart (1

level teaspoon [4 g] per spot). If you wish to try

discouraging moles by beginning a control program for

white grubs, contact your local extension agent for

recommended procedures.

Because moles feed largely

on insects and worms, the use of certain insecticides

may reduce their food supply, causing them to leave the

area. However, before doing so, they may increase their

digging in search of food, possibly increasing damage to

turf or garden areas. Check local sources of

insecticides for controlling grubs. Follow the label

instructions for use.

Fig. 4a. Moles push dirt through vertical tunnels onto

surface of ground. Mole hill Fig.

4b. Ridge caused by tunneling of mole under sod.

Plug Gopher mound Mole tunnel and hill Fig. 4c.

Comparison of gopher mound and mole hill. Mole fence

Frightening

Some electronic, magnetic,

and vibrational devices have been promoted as being

effective in frightening or repelling moles. None,

however, have been proven effective.

Repellents

No chemical products are

registered or effective for repelling moles. Borders of

marigolds may repel moles from gardens, although this

method has not been scientifically tested.

Toxicants

Since moles normally do

not consume grain, toxic grain baits are seldom

effective. Two poisons are federally registered for use

against moles. Ready-to-use grain baits containing

strychnine are sold at nurseries or garden supply

stores.

Recent work by Elshoff and

Dudderar at Michigan State University reported on the

use of Orco Mole Bait, a chlorophacinone pellet which is

used in Washington and some other states under 24(c)

permits for mole damage control. Even though the

researchers stated the use of this toxicant is a highly

effective and easily applied mole control technique,

there are disadvantages. Two or more successive

treatments are often required. An average of 21 1/2 days

was required to achieve zero damage on treated dry soil

and 39 days on treated irrigated soils.

Fumigants

Two fumigants, aluminum

phosphide and gas cartridges, are federally registered

for use against moles (see Supplies and Materials).

Aluminum phosphide is a Restricted Use Pesticide. These

fumigants have the greatest effectiveness when the

materials are placed in the mole’s deep burrows, not in

the surface runways. Golf course owners, however, report

that moles can be repelled from surface tunnels by

placing aluminum phosphide pellets in them. Since state

pesticide registrations vary, check with your local

extension or USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services office for

information on toxicants and repellents that are legal

in your area. Care should be taken when using chemicals.

Read and follow label instructions when using toxicants

and fumigants.

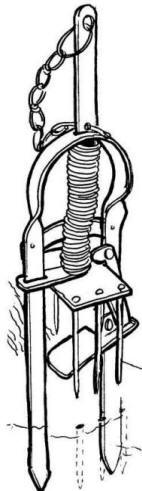

Trapping

Trapping is the most

successful and practical method of getting rid of moles.

There are several mole traps on the market. Each, if

properly handled, will give good results. The traps are

set over a depressed portion of the surface tunnel. As a

mole moves through the tunnel, it pushes upward on the

depressed tunnel roof and trips the broad trigger pan of

the trap. The brand names of the more common traps are:

Victor® mole trap, Out O’ Sight®, and Nash® (choker

loop) mole trap (Fig. 6). The Victor® trap has sharp

spikes that impale the mole when the spikes are driven

into the ground by the spring. The Out O’ Sight® trap

has scissorlike jaws that close firmly across the

runway, one pair on either side of the trigger pan. The

Nash® trap has a choker loop that tightens around the

mole’s body. Others include the Easy-Set mole

eliminator, Cinch mole trap, and the Death-Klutch gopher

trap.

a

B

B

Fig. 6. Mole traps: listed

in counter-clockwise order

(a) Out O’ Sight® (scissor-jawed), (b) Victor®

(harpoon), and (c) Nash® (choker loop).

These traps are well

suited to moles because the mole springs them when

following its natural instinct to reopen obstructed

passageways.

Success or failure in the

use of these devices depends largely on the operator’s

knowledge of the mole’s habits and of the trap

mechanism.

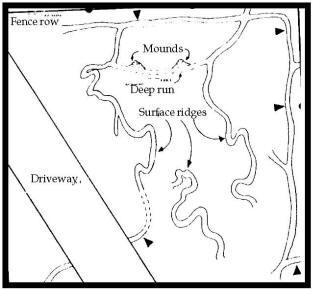

Fig. 7. A network of mole

runways in a yard. The arrowheads indicate good

locations to set traps. Avoid the twisting surface ridges and do not place traps on top of

mounds.

twisting surface ridges and do not place traps on top of

mounds.

To set a trap properly,

select a place in the surface runway where there is

evidence of fresh mole activity and where the burrow

runs in a straight line (Fig. 7). Dig out a portion of

the burrow, locate the tunnel, and replace the soil,

packing it firmly where the trigger pan will rest (Fig.

8).

To set the harpoon or

impaling-type trap, raise the spring, set the safety

catch, and push the supporting spikes into the ground,

one on either side of the runway (Fig. 9). The trigger

pan should just touch the earth where the soil is packed

down. Release the safety catch and allow the impaling

spike to be forced down into the ground by the spring.

This will allow the spike to penetrate the burrow when

the trap is sprung later. Set the trap and leave it. Do

not tread on or disturb any other portion of the mole’s

runway.

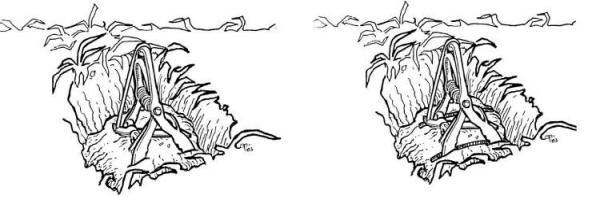

To

set a scissor-jawed trap, dig out a portion of a

straight surface runway, and repack it with fine soil.

Set the trap and secure it by a safety hook with its

jaws forced into the ground. It should straddle the

runway (Fig. 10a) until the trigger pan touches the

packed soil between the jaws. The points of the jaws are

set about 1 inch (2.5 cm) below the mole’s runway and

the trigger pan should rest on the portion as previously

described. Care should be taken to see that the trap is

in line with the runway so the mole will have to pass

directly between the jaws. In heavy clay soils be sure

to cut a path for the jaws (Fig. 10b) so they can close

quickly. The jaws of this trap are rather short, so be

sure the soil on the top of the mole run is low enough

to bring the trap down nearer to the actual burrow. Set

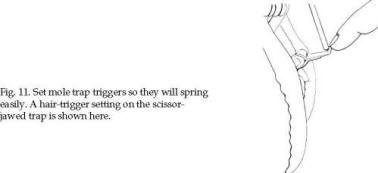

the triggers on both traps so that they will spring

easily (Fig. 11). Remember to release the safety hook

before releasing the trap. Be careful when handling

these traps. To

set a scissor-jawed trap, dig out a portion of a

straight surface runway, and repack it with fine soil.

Set the trap and secure it by a safety hook with its

jaws forced into the ground. It should straddle the

runway (Fig. 10a) until the trigger pan touches the

packed soil between the jaws. The points of the jaws are

set about 1 inch (2.5 cm) below the mole’s runway and

the trigger pan should rest on the portion as previously

described. Care should be taken to see that the trap is

in line with the runway so the mole will have to pass

directly between the jaws. In heavy clay soils be sure

to cut a path for the jaws (Fig. 10b) so they can close

quickly. The jaws of this trap are rather short, so be

sure the soil on the top of the mole run is low enough

to bring the trap down nearer to the actual burrow. Set

the triggers on both traps so that they will spring

easily (Fig. 11). Remember to release the safety hook

before releasing the trap. Be careful when handling

these traps.

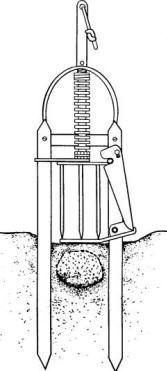

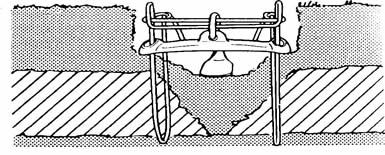

To set a choker trap, use

a garden trowel to make an excavation across the tunnel.

Make it a little deeper than the tunnel and just the

width of the trap. Note the exact direction of the

tunnel from the open ends, and place the set trap so

that its loop encircles this course (Fig. 12). Block the

excavated section with loose, damp soil from which all

gravel and debris have been removed. Pack the [Fig. 9.

Set the harpoon-type trap directly over the runway so

that its supporting stakes straddle the runway and its

spikes go into the runway.] soil firmly underneath the

trigger pan with your fingers and settle the trap so

that the trigger rests snugly on the built-up soil.

Finally, fill the trap hole with enough loose soil to

cover the trap level with the trigger pan and to exclude

all light from the mole burrow.

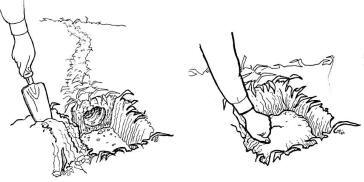

Fig. 8a. Excavation of a mole tunnel is the Fig. 8b.

Replace the soil loosely in the excavation. first step

in setting a mole trap.

Fig. 10a. Set the

scissor-jawed trap so that the jaws straddle the runway.

Fig. 10b. In heavy soils, make a path for the jaws to

travel so they can close quickly.

If a trap fails to catch a mole after 2 days, it can

mean the mole has changed its habits, the runway was

disturbed too much, the trap was improperly set, or the

trap was detected by the mole. In any event, move the

trap to a new location.

Fig. 12. The choker loop trap is set so that the loop

encircles the mole’s runway.

If one cares to take the

time, moles can be caught alive. Examine tunnels early

in the morning or evening where fresh burrowing

operations have been noted. Quietly approach the area

where the earth is being heaved up. Quickly strike a

spade into the ridge behind the mole and throw the

animal out onto the surface. A mole occasionally can be

driven to the surface by flooding a runway system with

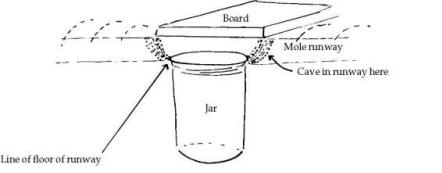

water from a hose or ditch. Another method is to bury a

3-pound (1.4-kg) coffee can or a wide-mouth quart (0.95

l) glass jar in the path of the mole and cover the top

of the burrow with a board (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13. A mole can be live-captured in a pit trap. Be

sure to use a board or other object to shut out all

light. Cave in the runway just in front of the jar on

both sides.

Other Methods

Nearly everyone has heard

of a surefire home remedy for controlling moles. In

theory, various materials placed in mole tunnels cause

moles to die or at least leave the area. Such cures

suggest placing broken bottles, ground glass, razor

blades, thorny rose branches, bleaches, various

petroleum products, sheep dip, household lye, chewing

gum, and even human hair in the tunnel. Other remedies

include mole wheels, pop bottles, windmills, bleach

bottles with wind vents placed on sticks, and similar

gadgets. Though colorful and sometimes decorative, these

gadgets add nothing to our arsenal of effective mole

control methods.

Another cure-all is the

so-called mole plant or caper spurge (Euphorbia latharis).

Advertisers claim that when planted frequently

throughout the lawn and flower beds, such plants

supposedly act as living mole repellents. No known

research supports this claim. Castor beans are also

supposed to repel moles. Caution must be used, however,

since castor beans are poisonous to humans. Several

electromagnetic devices or “repellers” have been

marketed for the control of rats, mice, gophers, moles,

ants, termites, and various other pests. Laboratory

tests have not proven these devices to be effective.

Unfortunately, there are no short cuts or magic wands

when controlling moles.

Economics of Damage and Control

Perhaps more problems are

encountered with moles than with any other single kind

of wild animal. Unfortunately, people lack an

appreciation of the importance of moles and the

difficulty of gaining complete control where habitats

are attractive to moles.

Before initiating a

control program for moles, be sure that they are truly

out of place. Moles play an important role in the

management of soil and of grubs that destroy lawns.

Moles work over the soil and subsoil. Only a part of

this work is visible at the surface. Tunneling through

soil and shifting of soil particles permits better

aeration of the soil and subsoil, carrying humus farther

down and bringing the subsoil nearer the surface where

the elements of plant food may be made available.

Moles eat harmful lawn

pests such as white grubs. They also eat beneficial

earthworms. Stomach analyses show that nearly two-thirds

of the moles studied had eaten white grubs.

If the individual mole is

not out of place, consider it an asset. If a particular

mole or moles are where you do not want them, remove the

moles. If excellent habitat is present and nearby mole

populations are high, control will be difficult. Often

other moles will move into recently vacated areas.

Acknowledgments

Figures 1 and 4 from

Schwartz and Schwartz (1981).

Figures 6, 8, 9, 10, 11,

12 and 13 adapted from various sources by Jill Sack

Johnson.

For Additional Information

Dudderar, G. R. Moles.

Univ. Michigan. Coop. Ext. Serv. Bull. E-863, 1 p.

Elshoff, D. K. and G. R.

Dudderar. 1989. The efeness of Orco mole bait in

controlling mole damage. Proc. Eastern Wildl.10magerol

Conf. 4: 205-209.

Godfrey, G., and P.

Crowcroft. 1960. The life of the mole. London Museum

Press, 152 pp.

Henderson, F. R. 1989.

Controlling nuisance moles. Coop. Ext. Serv. Kansas

State Univ. C-701, Manhattan.

Holbrook, H. T. and R. M.

Timm. 1986. Moles and their control. NebGuide G86-777.

Univ. Nebraska. Coop. Ext. Lincoln. 4 pp.

San Julian, G. J. 1984.

Moles. Coop. Ext. Serv. North Carolina State Univ.

NCADCM No. 134. 3 pp.

Schwartz, C. W. and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri. rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp.

Silver, J. and A. W.

Moore. 1933. Mole control. US Dep. Agric., Farmers Bull.

No. 1716, Washington, D.C.

Yates, T. L. and R. J.

Pedersen. 1982. Moles. Pages 37-51 in J. A. Chapman and

G. A. Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North America:

biology, management, and economics. The Johns Hopkins

Univ. Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom, Robert

M. Timm, Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|