|

|

|

|

|

OTHER MAMMALS: Armadillos |

|

|

Fig. 1. Armadillo,

Dasypus novemcinctus

Identification

The armadillo (Dasypus

novemcinctus) is a rather interesting and unusual

animal that has a protective armor of “horny” material

on its head, body, and tail. This bony armor has nine

movable rings between the shoulder and hip shield. The

head is small with a long, narrow, piglike snout. Canine

and incisor teeth are absent. The peglike cheek teeth

range in number from seven to nine on each side of the

upper and lower jaw. The long tapering tail is encased

in 12 bony rings. The track usually appears to be

three-toed and shows sharp claw marks. The armadillo is

about the size of an opossum, weighing from 8 to 17

pounds (3.5 to 8 kg).

Range

The armadillo ranges from

south Texas to the southeastern tip of New Mexico,

through Oklahoma, the southeastern corner of Kansas and

the southwestern corner of Missouri, most of Arkansas,

and southwestern Mississippi. The range also includes

southern Alabama, Georgia, and most of Florida (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Range of the armadillo in North America.

Habitat

The armadillo prefers

dense, shady cover such as brush, woodlands, forests,

and areas adjacent to creeks and rivers. Soil texture is

also a factor in the animal’s habitat selection. It

prefers sandy or loam soils that are loose and porous.

The armadillo will also inhabit areas having cracks,

crevices, and rocks that are suitable for burrows.

Food Habits

More than 90% of the

armadillo’s diet is made up of insects and their larvae.

Armadillos also feed on earthworms, scorpions, spiders,

and other invertebrates. There is evidence that the

species will eat some fruit and vegetable matter such as

berries and tender roots in leaf mold, as well as

maggots and pupae in carrion. Vertebrates are eaten to a

lesser extent, including skinks, lizards, small frogs,

and snakes, as well as the eggs of these animals.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

The armadillo is active

primarily from twilight through early morning hours in

the summer. In winter it may be active only during the

day. The armadillo usually digs a burrow 7 or 8 inches

(18 or 20 cm) in diameter and up to 15 feet (4.5 m) in

length for shelter and raising young. Burrows are

located in rock piles, around stumps, brush piles, or

terraces around brush or dense woodlands. Armadillos

often have several dens in an area to use for escape.

The young are born in a

nest within the burrow. The female produces only one

litter each year in March or April after a 150-day

gestation period. The litter always consists of

quadruplets of the same sex. The young are identical

since they are derived from a single egg.

The armadillo has poor

eyesight, but a keen sense of smell. In spite of its

cumbersome appearance, the agile armadillo can run well

when in danger. It is a good swimmer and is also able to

walk across the bottom of small streams.

Damage and Damage Identification

Most armadillo damage

occurs as a result of their rooting in lawns, golf

courses, vegetable gardens, and flower beds.

Characteristic signs of armadillo activity are shallow

holes, 1 to 3 inches (2.5 to 7.6 cm) deep and 3 to 5

inches (7.6 to 12.7 cm) wide, which are dug in search of

food. They also uproot flowers and other ornamental

plants. Some damage has been caused by their burrowing

under foundations, driveways, and other structures. Some

people complain that armadillos keep them awake at night

by rubbing their shells against their houses or other

structures.

There is evidence that

armadillos may be responsible for the loss of domestic

poultry eggs. This loss can be prevented through proper

housing or fencing of nesting birds.

Disease is a factor

associated with this species. Armadillos can be infected

by the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae, the causative

agent of leprosy. The role that armadillos have in human

infection, however, has not yet been determined. They

may pose a potential risk for humans, particularly in

the Gulf Coast region.

Legal Status

Armadillos are unprotected

in most states.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Armadillos have the

ability to climb and burrow. Fencing or barriers,

however, may exclude armadillos under certain

conditions. A fence slanted outward at a 40o angle, with

a portion buried, can be effective. The cost of

exclusion should be compared to other forms of control

and the value of the resources being protected.

Cultural Methods

Armadillos prefer to have

their burrows in areas that have cover, so the removal

of brush or other such cover will discourage them from

becoming established.

Repellents

None are currently

registered or known to be effective.

Toxicants

None are currently

registered.

Fumigants

None are currently

registered; however, there are some that are effective.

Since state pesticide registrations vary, check with

your local extension office or state wildlife agency for

information on pesticides that are legal in your area.

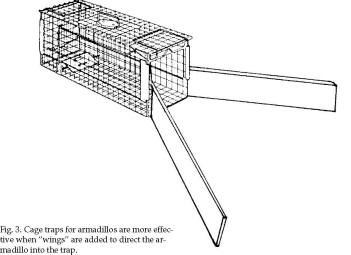

Trapping

Armadillos can be captured

in 10 x 12 x 32-inch (25 x 30.5 x 81-cm) live or box

traps, such as Havahart, Tomahawk, or homemade types.

The best locations to set traps are along pathways to

armadillo burrows and along fences or other barriers

where the animals may travel.

The best trap is the type

that can be opened at both ends. Its effectiveness can

be enhanced by using “wings” of 1 x 4-inch (2.5 x 10-cm)

or 1 x 6-inch (2.5 x 15-cm) boards about 6 feet (1.8 m)

long to funnel the target animal into the trap (Fig. 3).

This set does not need baiting. If bait is desired, use

overripe or spoiled fruit. Other suggested baits are

fetid meats or mealworms.

Other traps that may be

used are leghold (No. 1 or 2) or size 220 Conibear®

traps. These types should be placed at the entrance of a

burrow to improve selectivity. Care should be taken when

placing leghold traps to avoid areas used by nontarget

animals.

Shooting

Shooting is an effective

and selective method. The best time to shoot is during

twilight hours or at night by spotlight when armadillos

are active. A shotgun (No. 4 to BB-size shot) or rifle

(.22 or other small caliber) can be used. Good judgment

must be used in determining where it is safe to shoot.

Check local laws and ordinances before using shooting as

a control method.

Other Methods

Since most of the damage

armadillos cause is a result of their rooting for

insects and other invertebrates in the soil, soil

insecticides may be used to remove this food source and

make areas less attractive to armadillos.

Economics of Damage and Control

There are few studies

available on the damage caused by armadillos. The damage

they do is localized and is usually more of a nuisance

than an economic loss.

Acknowledgments

Figure 1 from Schwartz and

Schwartz (1981), adapted by Emily Oseas Routman.

Figure 2 adapted from Burt

and Grossenheider (1976) by Jill Sack Johnson.

Figure 3 by Jill Sack

Johnson.

For Additional Information

Chamberlain, P. A. 1980. Armadillos: problems and

control. Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 9:163-169.

Galbreath, G. J. 1982.

Armadillo. Pages 71-79 in J. A. Chapman and G. A.

Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North America: biology,

management and economics. The Johns Hopkins Univ. Press,

Baltimore.

Humphrey, S. R. 1974.

Zoogeography of the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus

novemcinctus) in the United States. BioSc. 24:457-462.

McBee, K., and R. J.

Baker. 1982. Dasypus novemcinctus. Mammal. Sp. 162:1-9.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom, Robert

M. Tim, Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|