|

|

|

|

|

OTHER MAMMALS: Wild Pigs |

|

|

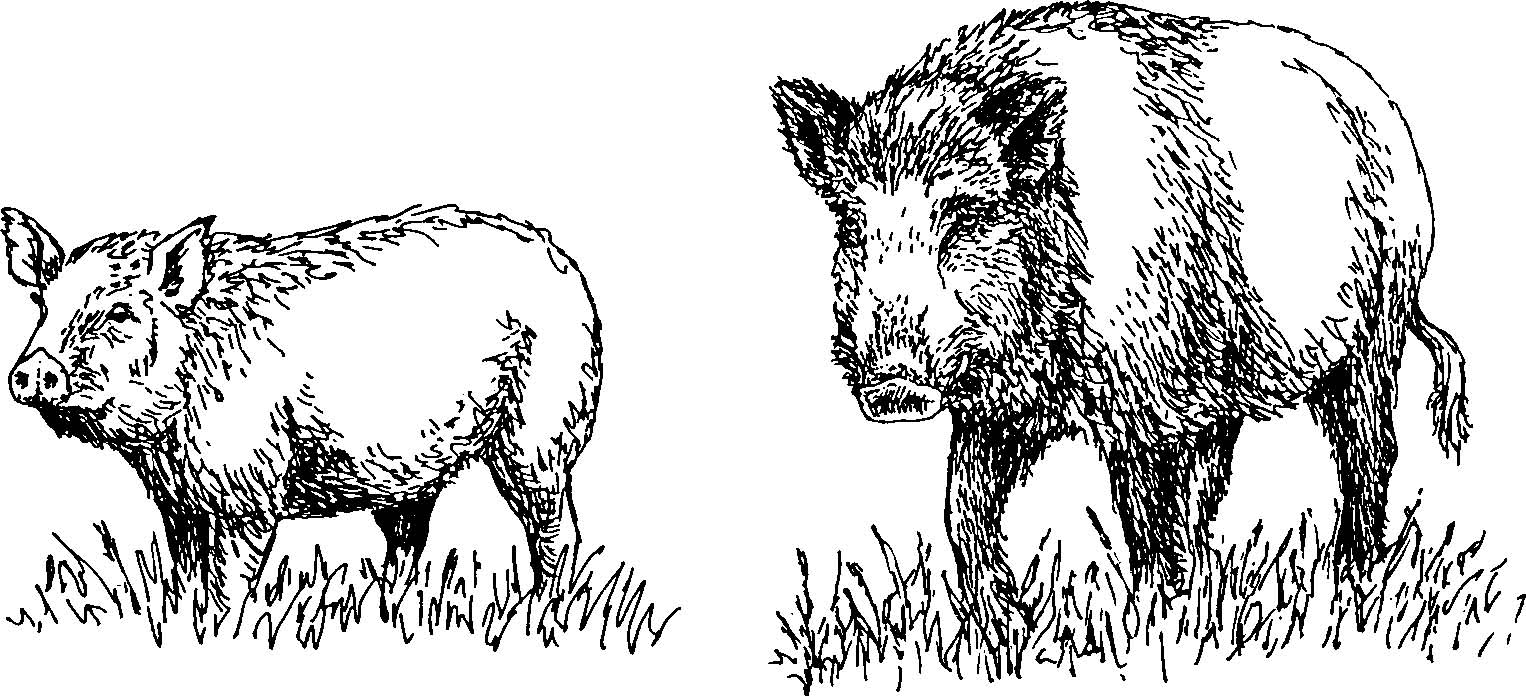

Fig. 1. Feral hog (left)

and European wild boar (right). Both are the species,

Sus scrofa.

Identification

Wild pigs (Sus scrofa,

Fig. 1) include both feral hogs (domestic swine that

have escaped captivity) and wild boar, native to Eurasia

but introduced to North America to interbreed with feral

hogs. Like domestic hogs, they may be any color. Their

size and conformation depend on the breed, degree of

hybridization with wild boar, and level of nutrition

during their growing period.

Wild boar have longer legs

and larger heads with longer snouts than feral hogs. The

color of young boar is generally reddish brown with

black longitudinal “watermelon” stripes. As the young

develop, the stripes begin to disappear and the red

changes to brown and finally to black. Both the male

feral hog and wild boar have continuously growing tusks.

Wild boar and feral hogs hybridize freely; therefore,

the term wild pig is appropriate as a generic term for

these animals.

Range

Christopher Columbus first

introduced members of the family Suidae into North

America in 1493 in the West Indies (Towne and Wentworth

1950). The first documented introduction to the United

States was in Florida by de Soto in 1593. More

introductions followed in Georgia and the Carolinas,

which established free-ranging populations in the

Southeast. Free-ranging practices continued until they

became illegal in the mid-twentieth century. Populations

of unclaimed hogs increased and spread throughout the

Southeast. Domestic hogs were released in California in

1769 and free-ranging practices there also resulted in a

feral hog population. European wild boar were released

at Hooper Bald, North Carolina, in 1912, and from there

introduced to California in 1925.

Wild pigs are found

throughout the southeastern United States from Texas

east to Florida and north to Virginia; and in

California, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands.

The local introduction of these animals for hunting

purposes occurred in North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas,

Louisiana, and California. The National Park Service

reports feral hogs in 13 National Park Service areas.

They occur in many state parks as well (Mayer and

Brisbin 1991). Feral hogs are also found in Hawaii,

Australia, New Zealand, and several other South Pacific

Islands.

Habitat

A variety of habitats,

from tidal marshes to mountain ranges, are suitable for

wild pigs. They prefer cover of dense brush or marsh

vegetation. They are generally restricted to areas below

snowline and above freezing temperatures during the

winter. Wild pigs frequent livestock-producing areas.

They prefer mast-producing hardwood forests but will

frequent conifer forests as well. In remote areas or

where human activities are minimal, they may use open

range or pastures, particularly at night. During periods

of hot weather, wild pigs spend a good deal of time

wallowing in ponds, springs, or streams, usually in or

adjacent to cover.

Food Habits

Types of food vary greatly

depending on the location and time of year. Wild pigs

will eat anything from grain to carrion. They may feed

on underground vegetation during periods of wet weather

or in areas near streams and underground springs. Acorns

or other mast, when available, make up a good portion of

their diet. Wild pigs gather in oak forests when acorns

fall, and their movements will generally not be as great

during this period. In the winters of poor mast years,

wild pigs greatly increase their range and consume

greater quantities of underground plant material,

herbaceous plants, and invertebrates (Singer 1981).

Stomach analyses indicate that wild hogs ingest flesh

from vertebrates, but the extent to which animals are

taken as prey or carrion is not known. Wild pigs are

capable of preying on lambs (Pavlov et al. 1981), as

well as goat kids, calves, and exotic game.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Wild pigs are intelligent

animals and readily adapt to changing conditions. They

may modify their response to humans fairly rapidly if it

benefits their survival. Wild boar have a greater

capacity to invade colder and more mountainous terrain

than do other wild pigs. Feral hogs feed during daylight

hours or at night, but if hunting pressure becomes too

great during the day, they will remain in heavy cover at

that time and feed at night. In periods of hot weather,

wild pigs remain in the shade in wallows during the day

and feed at night.

The wild pig is the most

prolific large wild mammal in North America. Given

adequate nutrition, a wild pig population can double in

just 4 months. Feral hogs may begin to breed before 6

months of age, if they have a high-quality diet. Sows

can produce 2 litters per year and young may be born at

any time of the year. Wild boar usually do not breed

until 18 months of age and commonly have only 1 litter

per year unless forage conditions are excellent. Like

domestic animals, the litter size depends upon the sow’s

age, nutritional intake, and the time of year. Litter

sizes of feral hogs in northern California average 5 to

6 per sow (Barrett 1978). Wild boar usually have litter

sizes of 4 to 5 but may have as many as 13 (Pine and

Gerdes 1973).

Damage

and Damage Identification

Wild pigs can cause a

variety of damage. The most common complaint is rooting

(sometimes called grubbing), resulting in the

destruction of crops and pastures. Damage to farm ponds

and watering holes for livestock is another common

problem. Predation on domestic stock and wildlife has

been a lesser problem in North America.

Damage to crops and

rangeland by wild pigs is easily identified. Rooting in

wet or irrigated soil is generally quite visible, but

can vary from an area of several hundred square feet

(m2) or more to only a few small spots where the ground

has been turned over. Rooting destroys pasture, crops,

and native plants, and can cause soil erosion. Wallows

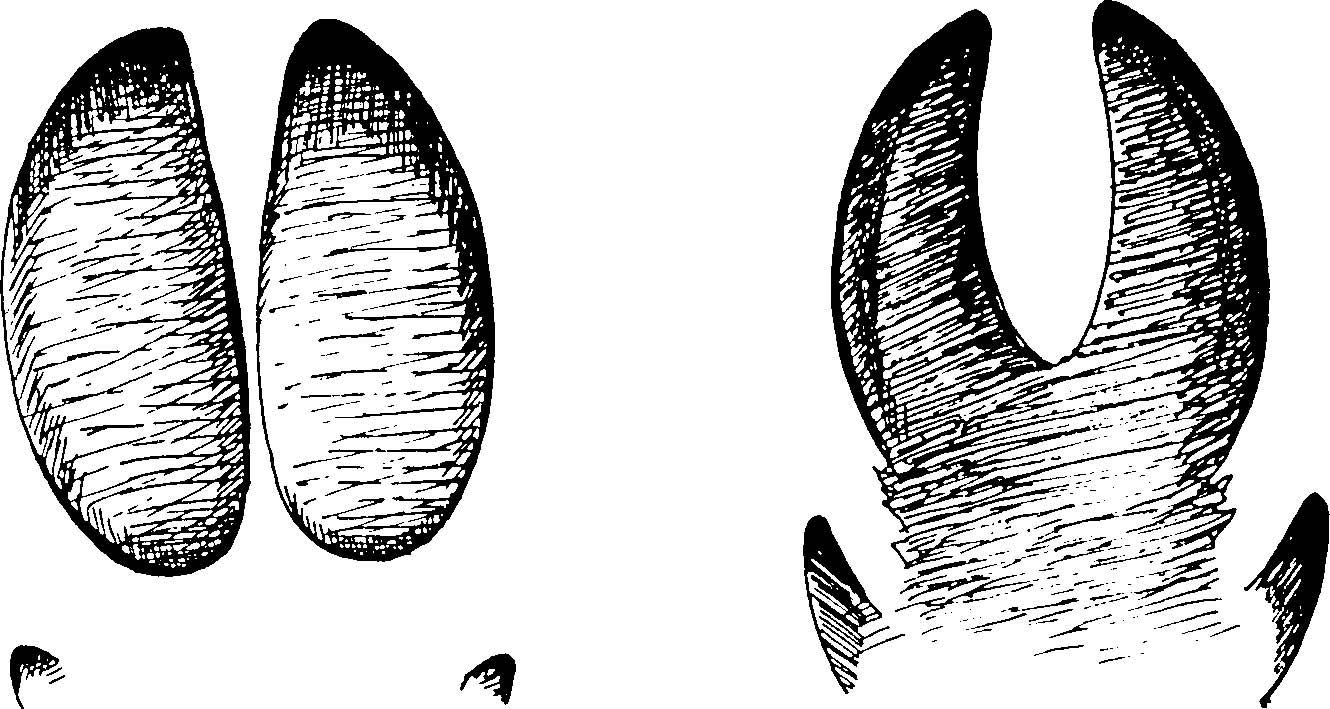

are easily seen around ponds and streams. Tracks of

adult hogs resemble those made by a 200pound (90-kg)

calf. Where ground is soft, dewclaws will show on adult

hog tracks (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Tracks of the feral hog (left) and European wild

boar (right).

Wild pig depredation on

certain forest tree seedlings has been a concern of

foresters in the South and West. Wild pigs have

destroyed fragile plant communities in Great Smoky

Mountains National Park and other preserves. They have

been known to damage fences when going into gardens and

can do considerable damage to a lawn or golf course in a

single night.

In California, wild pigs

have entered turkey pens, damaging feeders, eating the

turkey feed, and allowing birds to escape through

damaged fences. Wild pigs in New South Wales, Australia,

reportedly killed and ate lambs on lambing grounds.

Producers in Texas and California reported to

USDA-APHIS-ADC that 1,473 sheep, goats, and exotic game

animals were killed by wild pigs in 1991. Predation

usually occurs on lambing or calving grounds, and some

hogs become highly efficient predators. Depredation to

calves and lambs can be difficult to identify because

these small animals may be killed and completely

consumed, leaving little or no evidence to determine

whether they were killed or died of other causes and

then were eaten. Determining predation by wild hogs is

possible if carcasses are not entirely eaten, because

feral hogs follow a characteristic feeding pattern on

lambs (Pavlov and Hone 1982). Photographs and additional

information on wild pig predation may be found in the

booklet by Wade and Bowns (1982).

Always be aware of the

potential for disease transmission when feral hogs are

associated with domestic livestock. Cholera, swine

brucellosis, trichinosis, bovine tuberculosis, foot and

mouth disease, African swine fever, and pseudorabies are

all diseases that may be transmitted to livestock (Wood

and Barrett 1979). Bovine tuberculosis was transmitted

to beef cattle by wild hogs on the Hearst Ranch in

California in 1965. Pork that was infected with hog

cholera brought into Kosrae Island in the East Carolinas

resulted in the decimation of all domestic and feral

hogs on the island.

Legal Status

Wild pigs are game mammals

in California, Texas, Tennessee, North Carolina, Puerto

Rico, Hawaii, and Florida (Wood and Barrett 1979, Mayer

and Brisbin 1991). In California, a depredation permit

is required from the Department of Fish and Game to

conduct a control program or to take depredating

animals. Contact your state wildlife agency to determine

if a permit is required.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Fencing is generally not practical except in small areas

around yards and gardens. Heavy wire and posts must be

used, but if hogs are persistent, exclusion is almost

impossible. Electric fencing on the outside of the mesh

may be of some help, but it is difficult to maintain

over large areas. Electric fencing has been used

effectively in New South Wales, Australia. See the Deer

chapter for details on electric fencing.

Frightening No

methods are effective.

Repellents None are

registered.

Toxicants There are

no toxicants currently registered for controlling wild

pigs in the United States.

Trapping

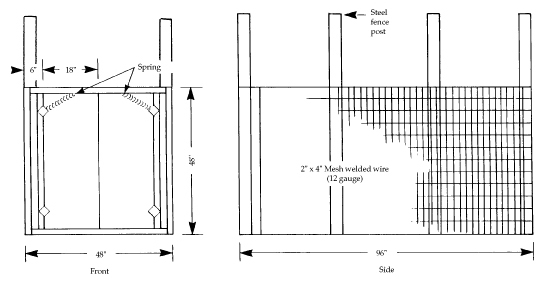

Cage Traps. Trapping, especially where pig densities

are high, is probably the most effective control method.

Traps may not be effective, however, during fall and

winter when acorns or other preferred natural foods are

available. Hogs seem to prefer acorns over grain and

other baits. Leg snares and hunting may be more

productive control methods during fall and winter.

Stationary corral-type traps and box traps have been

used with success. The corral or stationary trap is

permanent and should be constructed in locations where

large populations of hogs are evident and where more

than one hog can be trapped at a time (Fig. 3). Build

the trap out of steel fence posts and 2 x 4-inch (5.1 x

10.2-cm) welded 12-gauge wire fencing. A gate frame can

be made from 2 x 4-inch (5.1 x 10.2-cm) boards. Make

doors from 3/4-inch (1.9-cm) plywood and mount them so

that they open inward and close automatically with

screen door springs. Heavier material may be used for

the gate and frame in areas where exceptionally large

hogs are to be trapped. Also, more steel fence posts may

be needed to reinforce the wire fencing. The wire

fencing should be put on the ground as well as at the

top of the trap to prevent hogs from going under the

sides or over the top. Fasten the sides to the top and

bottom. One or two small hogs can be left inside the

trap with adequate food and water to act as decoys.

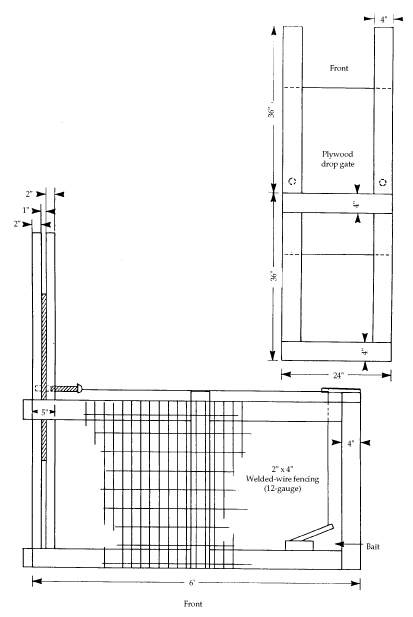

A portable trap with a

drop gate has been used very effectively and can be

moved from one area to another (Fig. 4). It is

especially effective where hogs occur intermittently.

Build the trap out of 2 x 4-inch (5.1 x 10.2-cm) welded

12-gauge wire over a 2 x 4-inch (5.1 x 10.2-cm) wooden

frame using a 3/4-inch (1.9-cm) plywood drop gate. Place

loose barbed wire fencing around the outside of the trap

to prevent livestock from entering and to protect both

the traps and bait material. When traps are not in use

make sure trap doors are locked shut to prevent the

possibility of trapping livestock.

There are a number of

different styles of live or cage traps. The two

described here have been used effectively in California.

As many as 14 hogs have been trapped during a night in

one trap. It is important that the material used in the

construction of these traps be strong and heavy enough

to prevent escapes. Corral-type traps have captured up

to 104 hogs in a single night and may have to be

reinforced with extra fence posts and heavier fencing

material.

Fig. 3. Stationary hog

trap.

2" x 4" x 24' wood

36" x 48" x 3/4" plywood

36' x 2" x 4" mesh welded wire

4 6" strap hinges

2 12" screen door springs

8 6" steel fence posts 4 lbs.

16-penny nails 1 lb.

12-penny nails 2 lbs.

1 1/2" staples 1

100' 12-gauge wire

Persistence and dedication

are required if a feral hog control program is to be

successful. Traps must be checked daily to be reset and

to replace bait when needed. Many times control measures

fail because operators fail to check their traps or

provide bait in adequate amounts. Trapping hogs that are

feeding on acorns may be difficult because they seem to

prefer acorns to grain or other baits.

Traps should be checked

from a distance when possible. If several large hogs are

in a trap, the presence of a person or vehicle will

frighten them and escapes can occur even out of

well-built traps. A well-placed shot to the head from a

large-caliber rifle will kill the hog instantly without

greatly alarming other hogs in the trap. Shoot the

largest hog first, if possible. When a trapping program

is being conducted, all hunting in the area should

cease, especially the use of dogs, as this may pressure

the pigs to move to another area.

A prebaiting program

should be conducted before a trapping program is

initiated. Grains such as barley, corn, or oats make

good attractants, as do vegetables or fruits, if a

supply is available. If bait is accepted by hogs,

replace it daily. Make sure enough bait is out to induce

hogs to return the next day; if no feed is available,

they may move on to other feeding areas. A place where

hogs have gathered in the past and seem to frequent

often, is probably a good place to build a cor-ral-type

trap. If only one or two hogs are attracted to the

prebait, a portable trap should be installed.

Fig. 4. Portable hog trap

with drop gate

8 2" x 4" x 6'

4 2" x 4" x 3'

6 2" x 4" x 2'

1 3/4" x 24" x 36" plywood

2 3' x 6' welded-wire fencing (12-gauge)

2 2' x 6' welded-wire fencing (12-gauge)

1 2' x 3' welded-wire fencing (12-gauge)

2 3" strap hinges

1 12" x 20" plywood

2 8' cable or nylon

2 1" x 1" steel pin

16-penny nails

If a swing gate corral

trap is prebaited, prop the doors open so that hogs can

move in and out. When it appears that the number of hogs

that are accepting the bait has peaked, position the

doors so that they will close after hogs enter the trap.

Steel Traps. Steel

leghold traps are not recommended for pigs.

Leg Snares Leg

snares can be used with success where terrain prohibits

the use of cage traps. Snares are not recommended if

livestock, deer, or other nontarget animals are in the

area. An ideal location for leg snares is at a fence

where hogs are entering pens or on trails that hogs are

traveling. Fasten the snare to a heavy drag, such as an

oak limb, 6 to 12 feet (1.8 to 3.6 m) in length, or

longer if large hogs are in the area. Make sure the size

of the cable is heavy enough to hold a large hog.

Shooting

Sport hunting is used in certain areas to reduce

wild pig densities and can be a source of revenue for

ranchers. Success is highly dependent on local

situations and terrain. Hunting is not recommended if

there is a serious depredation or disease problem.

Unsuccessful hunting will make wild pigs keep to cover

and change their feeding habits. The use of dogs can

increase hunter success. Good dogs chase pigs from cover

where they can be shot by hunters.

Economics of Damage and Control

In most areas it is

unlikely that wild pigs can be exterminated. It is

theoretically possible, but the cost to do so is usually

prohibitive. Landowners must generally accept the fact

that they will always have some wild pigs and should

therefore plan for a long-term control program.

Feral hog damage can be

extensive and costly if not controlled. Control for

disease suppression is extremely expensive because many

hogs need to be eliminated. Crop depredations may cease

after one or two hogs are shot or trapped, or

intermittent hunting pressure is put on them. They

simply move to new areas. If depredations are heavy

enough to require a reduction in the overall population

then a program can be very costly, depending on the size

of the area involved.

Acknowledgments

Figures 1 and 2 by Emily

Oseas Routman.

Figures 3 and 4 by Marilyn

Murtos, US Bureau of Reclamation, Sacramento,

California.

For Additional Information

Barrett, R. H. 1970.

Management of feral hogs on private lands. Trans.

Western Sect. Wildl. Soc. 6:71-78.

Barrett, R. H. 1977. Wild

pigs in California. Pages 111-113 in G. W. Wood, ed.

Research and management of wild hog populations. Symp.

Belle W. Baruch For. Sci. Inst., Clemson Univ.,

Georgetown, South Carolina.

Barrett, R. H. 1978. The

feral hog on the Dye Creek Ranch, California. Hilgardia

46:283-355.

Barrett, R. H., B. L.

Goatcher, P. J. Gogan, and E.

L. Fitzhugh. 1988.

Removing feral pigs from Annadel State Park. Trans.

Western Sect. Wildl. Soc. 24:47-52.

Bratton, S. P. 1974. The

effect of the European wild boar (Sus scrofa) on the

high elevation vernal flora in Great Smoky Mountains

National Park. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 101:198-206.

Mayer, J. J., and I. L.

Brisbin, Jr. 1991. Wild pigs of the United States: their

history, morphology, and current status. Univ. Press,

Athens, Georgia. 313 pp.

Pavlov, P. M., and J.

Hone. 1982. The behavior of feral pigs, Sus scrofa, in a

flock of lambing ewes. Australian Wildl. Resour.

9:101-109.

Pavlov, P. M., J. Hone, R.

J. Kilgour, and H. Pedersen. 1981. Predation by feral

pigs on Merino lambs at Nyngan, New South Wales.

Australian J. Exp. Agric. An. Husb. 21:570-574.

Pine, D. S., and C. S.

Gerdes. 1973. Wild pigs in Monterey county, California.

California Fish Game 59:126-137.

Plant, J. W. 1977. Feral

pigs predators of lambs. Agric. Gazette, New South Wales

Dep. Agric. Vol. 8, No.5.

Plant, J. W. 1980.

Electric fences give pigs a shock. Agric. Gazette, New

South Wales Dep. Agric. Vol. 91, No. 2.

Singer, F. J. 1981. Wild

pig populations in the national parks. Environ. Manage.

5:263-270.

Singer, F. J., D. K. Otto,

A. R. Tipton, and C. P. Hable. 1981. Home range

movements and habitat use of wild boar. J. Wildl.

Manage. 45:343-353.

Sterner, J. D., and R. H.

Barrett. 1991. Removing feral pigs from Santa Cruz

Island, California. Trans. Western Sect. The Wildl. Soc.

27:47-53.

Tisdell, C. A. 1982. Wild

pigs: environmental pest or economic resource? Pergamon

Press, New York. 445 pp.

Towne, C. W., and E. N.

Wentworth. 1950. Pigs from Cave to Cornbelt. Univ.

Oklahoma Press, Norman. 305 pp.

Wade, D. A., and J. E.

Bowns. 1982. Procedures for evaluating predation on

livestock and wildlife. Bull. B-1429, Texas A & M Univ.,

College Station. 42 pp.

Wood, C. W., and R.

Barrett. 1979. Status of wild pigs in the United States.

Wildl. Soc. Bull. 7:237-246.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|