|

|

|

|

|

OTHER MAMMALS: Shrews |

|

|

Fig. 1. A masked shrew,

Sorex cinereus

Identification

The shrew is a small,

mouse-sized mammal with an elongated snout, a dense fur

of uniform color, small eyes, and five clawed toes on

each foot (Fig. 1). Its skull, compared to that of

rodents, is long, narrow, and lacks the zygomatic arch

on the lateral side characteristic of rodents. The teeth

are small, sharp, and commonly dark-tipped. Pigmentation

on the tips of the teeth is caused by deposition of iron

in the outer enamel. This deposition may increase the

teeth’s resistance to wear, an obvious advantage for

permanent teeth that do not continue to grow in response

to wear. The house shrew (Suncus murinus) lacks the

pigmented teeth. Shrew feces are often corkscrew-shaped,

and some shrews (for example, the desert shrew [Notiosorex

crawfordi]) use regular defecation stations. Albino

shrews occur occasionally. Shrews are similar to mice

except that mice have four toes on their front feet,

larger eyes, bicolored fur, and lack an elongated snout.

Moles also are similar to shrews, but are usually larger

and have enlarged front feet. Both shrews and moles are

insectivores, whereas mice are rodents.

Worldwide, over 250

species of shrews are recognized, with over 30 species

recognized in the United States, the US Territories, and

Canada (Table 1). Specific identification of shrews may

be difficult. Taxonomists are still refining the

phylogenetic relationships between populations of

shrews. Consult a regional reference book on mammals, or

seek assistance from a qualified mammalogist.

Range

Shrews are broadly

distributed throughout the world and North America. For

specific range information, refer to one of the many

references available on mammal distribution for your

region. Publications by Burt and Grossenheider (1976),

Hall (1981), and Junge and Hoffmann (1981) are

particularly helpful.

Habitat

Shrews vary widely in

habitat preferences throughout North America. Shrews

exist in practically all terrestrial habitats, from

montane or boreal regions to arid areas. The northern

water shrew (Sorex palustris) prefers marshy or

semiaquatic areas. Regional reference books will help

identify specific habitats. A word of caution is in

order, however. Distribution studies based on the

results of snap-trapping research have a pronounced

tendency to understate the abundance of shrews. Studies

using pit traps are more successful in assessing the

presence or absence of shrews in a particular location.

Food Habits

Shrews are in the

taxonomic order Insectivora. As the name implies,

insects make up a large portion of the typical shrew

diet. Food habit studies have revealed that shrews eat

beetles, grasshoppers, butterfly and moth larvae,

ichneumonid wasps, crickets, spiders, snails,

earthworms, slugs, centipedes, and millipedes. Shrews

also eat small birds, mice, small snakes, and even other

shrews when the opportunity presents itself. Seeds,

roots, and other vegetable matter are also eaten by some

species of shrews.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Shrews are among the

world’s smallest mammals. The pigmy shrew (Sorex hoyi)

is the smallest North American mammal. It can weigh as

little as 0.1 ounce (2 g). Because of their small size,

shrews have a proportionally high sur-face-to-volume

ratio and lose body heat rapidly. Thus, to maintain a

constant body temperature, they have a high metabolic

rate and need to consume food as often as every 3 to 4

hours. Some shrews will consume three times their body

weight in food over a 24-hour period.

Shrews usually do not live

longer than 1 to 2 years, but they have 1 to 3 litters

per year with 2 to 10 young per litter. Specific

demographic features vary with the species. The

gestation period is approximately 21 days.

Shrews have an acute sense

of touch, hearing, and smell, with vision playing a

relatively minor role. Some species of shrews use a

series of high-pitched squeaks for echolocation, much as

bats do. However, shrews probably use echolocation more

for investigating their habitat than for searching out

food. Glands located on the hindquarters of shrews have

a pungent odor and probably function as sexual

attractants. Blarina brevicauda, and presumably B.

carolinensis and B. hylophaga (the short-tailed shrews),

have a toxic venom in their saliva that may help them

subdue small prey.

Some shrews are mostly

nocturnal; others are active throughout the day and

night. They frequently use the tunnels made by voles and

moles. During periods of occasional abundance, shrews

may have a strong, although temporary, negative impact

on mouse or insect populations. Many predators kill

shrews, but few actually eat them. Owls in particular

consume large numbers of shrews.

Some shrews exhibit

territorial behavior. Depending on the species and the

habitat, shrews range in density from 2 to 70

individuals per acre (1 to 30/ hectare) in North

America.

Damage

Most species of shrews do

not have significant negative impacts and are not

abundant enough to be considered pests (Schmidt 1984).

Shrews sometimes conflict with humans, however. The

vagrant shrew (Sorex vagrans) has been reported to

consume the seeds of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii),

although the seeds constitute a minor part of the diet.

The masked shrew (Sorex cinereus) destroyed from 0.3% to

10.5% of white spruce (Picea glauca) seeds marked over a

6-year period (Radvanyi 1970). Lodgepole pine (Pinus

contorta) seeds are also eaten by the masked shrew.

Radvanyi (1966, 1971) has published pictures of shrew,

mouse (Peromyscus, Microtus, and Clethrionomys spp.),

and chipmunk (Eutamias spp.) damage to lodgepole pine

seeds, and describes shrew damage to white spruce seeds.

The northern water shrew (Sorex

palustris) may cause local damage by consuming eggs or

small fish at hatcheries. The least shrew (Cryptotis

parva), also known as the bee shrew, sometimes enters

hives and destroys the young brood (Jackson 1961). The

northern short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) has

been reported to damage ginseng (Panax spp.) roots.

Short-tailed and masked shrews reportedly can climb

trees where they can feed on eggs or young birds in a

nest or consume suet in bird feeders.

The pugnacious nature of

shrews sometimes makes them a nuisance when they live in

or near dwellings. Shrews occasionally fall into window

wells, attack pets, attack birds or chipmunks at

feeders, feed on stored foods, contaminate stored foods

with feces and urine, and bite humans when improperly

handled. Potential exists for the transmission of

diseases and parasites, but this is poorly documented.

The house shrew (Suncus

murinus) is an introduced species to Guam. It has been

reported as a host for the rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis)

which can carry the plague bacillus (Yersinia pestis) (Churchfield

1990). Compared to rat (Rattus spp.) numbers, however,

house shrew numbers are usually low, and risk of plague

transmission is probably minimal. The house shrew is

accustomed to living around humans and houses, which

increases its damage potential. It is considered smelly

and noisy, making incessant, shrill, clattering sounds

as it goes along (Churchfield 1990:149). On occasion it

destroys stored grain products.

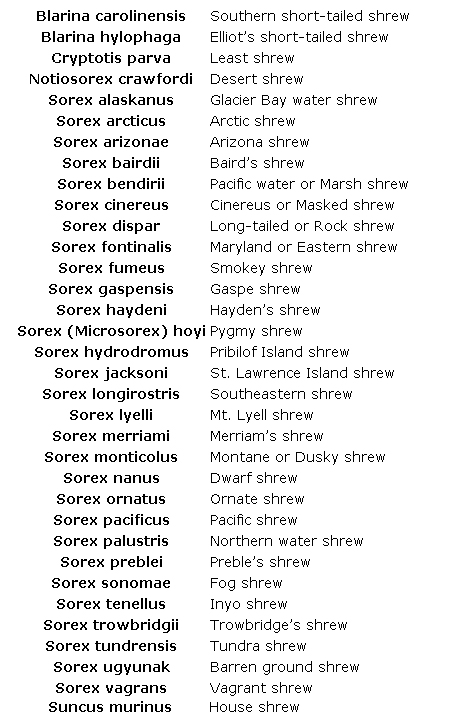

Table 1. Shrews of the

United States, the US Territories, and Canada (from

Legal Status Banks et al. 1987, and Jones et al. 1992).

Shrews are not protected

by federal Scientific name Common name laws, with one

exception. The south-eastern shrew (Sorex longirostris

fischeri) is protected in the Great Dismal Swamp in

Virginia and North Carolina by the Endangered Species

Act of 1973. Nowak and Paradiso (1983:131) list the

following additional species or populations of concern:

Sorex preblei, Sorex trigonirostri, and Sorex merriami

in Oregon; Sorex trigonirostri eionis in Florida along

the Homossassee River; and Sorex palustris punctulatus

in the southern Appalachians.

Some states may have

special regulations regarding the collection or killing

of nongame mammals. Consult your local wildlife agency

or Cooperative Extension office for up-to-date

information.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Rodent-proofing will also exclude shrews from

entering structures. Place hardware cloth of 1/4-inch

(0.6-cm) mesh over potential entrances to exclude

shrews. The pygmy shrew (Sorex hoyi) may require a

smaller mesh. Coarse steel wool placed in small openings

can also exclude shrews.

Cultural Methods

Regular mowing around structures should decrease

preferred habitat and food, and may increase predation.

Where shrews are eating tree seeds, plant seedlings

instead to eliminate damage.

Repellents No

repellents are registered for use against shrews.

Toxicants No

toxicants are registered to poison shrews.

Fumigants

No fumigants are registered for use against shrews.

It would be impractical to use fumigants because of the

porous nature of typical shrew burrows.

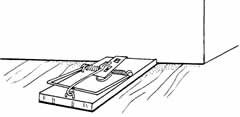

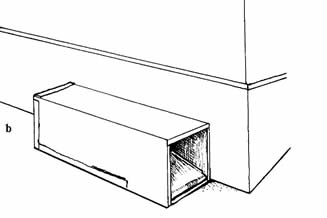

Trapping

Mouse traps (snap traps), box traps, and pit traps

have been used to collect shrews. Set mouse traps in

runways or along walls, with the traps set at a right

angle to the runway and the triggers placed over the

runway (Fig. 2a). Small box traps can be set parallel to

and inside of runways, or parallel to walls around

structures (Fig. 2b). Bait the traps with a mixture of

peanut butter and rolled oats. A small amount of bacon

grease or hamburger may increase the attractiveness of

the bait.

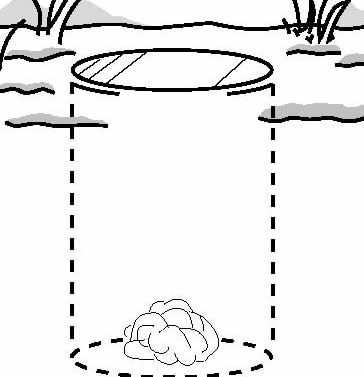

A pit trap consists of a

gallon jar or a large can sunk into the ground under a

runway until the lip of the container is level with the

runway itself (Fig. 2c). Bait is not necessary. A small

amount of bacon grease smeared around the top of the

container may be an effective attractant, but this may

also attract large scavengers. Pit traps are more

effective for capturing shrews than snap traps, although

the increased labor involved in setting a pit trap may

not be justified when trying to capture only one or two

animals. Monitor pit traps daily, preferably in the

morning before the temperature gets hot, although

Churchfield (1990) recommends checking traps four times

in a 24-hour period. Place cotton wool in the pit trap

containers to reduce the mortality of trapped animals.

This is especially important to ensure the successful

release of nontarget animals. Since shrews are generally

beneficial in consuming insects, live-captured animals

can be relocated in suitable habitat more than 200 yards

(193 m) from the capture site.

The traps and placement

procedures described above are also effective for

catching mice. Note the identification characteristics

given above for determining whether the captured animal

is indeed a shrew. Sometimes birds are captured in traps

set for shrews. If this occurs, try placing a cover over

the traps, a cover over the bait, moving the traps to

another location, or omitting rolled oats from the bait

mixture.

Traps for Capturing Shrews

Fig. 2. Traps and trap

placement for capturing shrews: a) mouse trap (snap

trap) set perpendicular to wall, with trigger next to

wall; b) box trap set parallel to wall; c) pit trap sunk

in ground over runway (includes cotton wool).

A

c

Shooting

Shooting is not practical and is not recommended. It

is illegal in some states and localities.

Other Methods

Owls may reduce local populations of shrews in poor

habitats, but this has not been documented. Domestic

cats appear to be very good predators of shrews,

although they seldom eat them (presumably because of the

shrew’s unpleasant odor). Cats may be effective at

temporarily reducing localized shrew populations living

in poor cover around structures. Cat owners may find

dead, uneaten shrews brought inside the home. Rather

than reduce the shrew population outside to prevent

this, simply monitor locations regularly used by your

cat, and dispose of dead shrews by placing a plastic bag

over your hand, picking up the dead animal, turning the

bag inside out while holding the shrew, sealing the bag,

and discarding it with the garbage. Using a plastic bag

in this manner reduces the potential for flea, tick,

helminth parasite, or disease transmission.

Economics of Damage and Control

No studies concerning the economics of shrew

damage and control are available. In Finland, shrews

appear to play a more important role as predators of

conifer seeds than they do in North America. Overall,

the economics of damage by shrews is not considered

great.

Folklore and Etymology

Chambers (1979) reviewed

some aspects of shrew biology and folklore: At one time

in Europe it was thought that if a shrew ran across a

farm animal that was lying down, the animal would suffer

intense pain. To counteract this, a shrew would be

walled up in an ash tree (a ‘shrew ash’), and then a

twig taken from the tree would be brushed onto the

suffering animal to relieve the pain. The ancient

Egyptians believed the shrew to be the spirit of

darkness. The shrew has also been mentioned as a Zuni

beast god, providing protection for stored grains from

raids by rats and mice (Hoffmeister 1967).

At least one tall tale

involving shrews has been found to be true. The

discovery that some shrews possess a toxic venom

confirms stories about the poisonous bite of shrews.

The etymology of the word

shrew is also interesting. The Old English form of the

word was screawa, or shrew-mouse. The Middle English

form was shrewe, meaning an evil or scolding person.

Thus shrew has a double meaning. It defines the small

mammal as well as an ill-tempered, scolding human

(usually female).

Shrews are in the family

Soricidae. Soricis is the genitive form of sorex, a

Latin word for shrew-mouse.

Acknowledgments

I appreciate the

assistance and comments of C. L. Shugart, S. E.

Hygnstrom, and four anonymous reviewers while developing

this manuscript. L. Thomas and J. Shepard provided

up-to-date information on the legal status of Sorex

longirostris fischeri.

Figure 1 is reproduced

with permission from Schwartz and Schwartz (1981).

Figure 2 was drawn by Jill

Sack Johnson.

For Additional Information

Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, and A. L. Gardner, eds.

1987. Checklist of vertebrates of the United States, the

US Territories, and Canada. US Dep. Inter, Fish Wildl.

Serv., Resour. Pub. 166. 79 pp.

Burt, W. H., and R. P.

Grossenheider. 1976. A field guide to the mammals.

Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. 289 pp.

Chambers, K. A. 1979. A

country-lover’s guide to wildlife. The Johns Hopkins

Univ. Press, Baltimore, Maryland 228 pp.

Churchfield, S. 1990.

Thenatural history of shrews. Cornell Univ. Press,

Ithaca, New York. 178 pp.

Fowle, C. D., and R. Y.

Edwards. 1955. An unusual abundance of short-tailed

shrews, Blarina brevicauda. J. Mammal. 36:36-41.

Hall, E. R. 1981. The

mammals of North America. Vol. 1. John Wiley and Sons,

New York. 690 pp.

Hoffmeister, D. F. 1967.

An unusual concentration of shrews. J. Mammal.

48:462-464.

Jackson, H.H.T. 1961.

Mammals of Wisconsin. Univ. Wisconsin Press, Madison.

504 pp.

Jones, J. K., Jr., R. S.

Hoffmann, D. R. Rice, C. Jones, R. J. Baker, and M. D.

Engstrom. 1992. Revised checklist of North American

mammals north of Mexico, 1991. Occas. Papers Mus. Texas

Tech Univ. 146:1-23.

Junge, J. A., and R. S.

Hoffmann. 1981. An annotated key to the long-tailed

shrews (genus Sorex) of the United States and Canada,

with notes on Middle American Sorex. Univ. Kansas, Mus.

Nat. Hist., Occas. Papers 94:1-48.

Martin, I. G. 1981. Venom

of the short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) as an

insect immobilizing agent. J. Mammal. 62:189-192.

Nowak, R. M., and J. L.

Paradiso. 1983. Walker’s mammals of the world. Vol. 1.

The Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore, Maryland. 568

pp.

Radvanyi, A. 1966.

Destruction of radio-tagged seeds of white spruce by

small mammals during summer months. For. Sci.

12:307-315.

Radvanyi, A. 1970. Small

mammals and regeneration of white spruce forests in

western Alberta. Ecol. 51:1102-1105.

Radvanyi, A. 1971.

Lodgepole pine seed depredation by small mammals in

western Alberta. For. Sci. 17:213-217.

Schmidt, R. H. 1984. Shrew

damage and control: a review. Proc. Eastern Wildl.

Damage Control Conf. 1:143-146.

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri, rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp.

Tomasi, T. E. 1979.

Echolocation by the short-tailed shrew Blarina

brevicauda. J. Mammal. 60:751-759.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert M. Timm Gary E.

Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|