|

|

|

|

|

OTHER MAMMALS: Pronghorn Antelope |

|

|

Fig. 1. Pronghorn

antelope, Antilocapra americana

Identification

The pronghorn (Antilocapra

americana) is not a true antelope but in a family by

itself (Antilocapridae). It is native only to

North America.

The pronghorn is the only

North American big game animal that has branched horns,

from which its name derives. Pronghorns have true horns

— derived from hair — not antlers. The horns have an

outer sheath of fused, modified hair that covers a

permanent, bony core. Pronghorns shed the hollow outer

sheath each year in October or November and grow a new

set by July. Both bucks and does have horns, but doe

horns are shorter and more slender. Adult pronghorns

stand 3 feet (90 cm) high at the shoulders. Bucks weigh

about 110 pounds (50 kg); does weigh about 80 pounds (36

kg). Pronghorns have a bright reddish-tan coat marked

with white and black. The buck has a conspicuous black

neck patch below the ears, which is lacking on the doe.

At a distance, their markings break up the outline of

their body, making them difficult to see. Their white

rump patch is enlarged and conspicuous when they are

alarmed. The flash of white serves as a warning signal

to other pronghorns and is visible at long distances.

Fig. 2. Range of the pronghorn in North America.

Range

Pronghorns currently have

a scattered but widespread distribution throughout

western North America (Fig. 2)

In the early 1800s, when

the Lewis and Clark expedition recorded the presence of

large herds of pronghorn, the total population across

North America was estimated at 35 million. In less than

100 years, however, intensive market hunting brought

pronghorn numbers to a low of approximately 13,000.

Quick action by conservation-minded leaders saved the

pronghorn from possible extinction.

In the late 1800s and

early 1900s most Great Plains state legislatures passed

laws making it unlawful to kill, ensnare, or trap

pronghorns.

Pronghorns were given

complete protection for nearly 50 years. In the 1940s

and 1950s, limited hunting seasons were permitted, and

pronghorn seasons have been held ever since in most

Great Plains states. Populations have shown a notable

increase in the last 2 decades.

A game management success

story documents an increase from a population low of a

few bands of pronghorn in Nebraska during the early

1900s to a current population of about 7,000. Trapping

and transplanting programs to reestablish pronghorn

populations by the state wildlife agencies and proper

management and protection have been major factors in the

pronghorn’s recovery.

Habitat

Pronghorns thrive in short

and mixed grasslands and sagebrush grasslands. They

prefer rolling, open, expansive terrain at elevations of

3,000 to 6,000 feet (900 to 1,800 m), with highest

population densities in areas receiving an average of 10

to 15 inches (25 to 38 cm) of precipitation annually.

Vegetation heights on good pronghorn ranges average 15

inches (38 cm) with a minimum of 50% ground cover of

mixed vegetation. Healthy pronghorn populations are

seldom found more than 3 to 4 miles (4.8 to 6.4 km) from

water.

Pronghorns sometimes

migrate between their summer and winter ranges. Since

they seldom jump over objects more than 3 feet (90 cm)

high, most fences stop them unless they can go under or

through them. The construction of many highways with

parallel fencing has greatly altered the migratory

patterns of pronghorns. Woven wire fences, in

particular, are a barrier that impede pronghorn

movements to water, wintering grounds, and essential

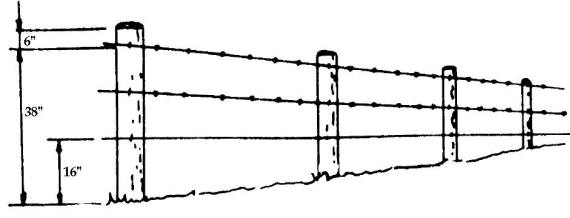

forage. Proper spacing of barbed wire in fences (Fig. 3)

is essential to allow adequate pronghorn movement.

Food Habits

Pronghorns eat a variety

of plants, mostly forbs and browse. Sagebrush often

makes up a large part of their diet. They are dainty

feeders, plucking only the tender, green shoots.

Pronghorns compete with sheep for forbs, but are often

found on summer cattle ranges where cattle eat the

grasses, leaving the forbs and browse. Dietary overlap

of pronghorns with sheep and cattle was 40% and 15%,

respectively, in New Mexico. In the winter, pronghorns

often feed in winter wheat and alfalfa fields.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Pronghorns depend on their

eyesight and speed to escape enemies. Their eyes

protrude in such a way that they can see in a side

direction. They prefer to live on the open plains where

they can see for long distances. Pronghorns are the

fastest North American big game animal and can reach

speeds of up to 60 miles per hour (96 kph).

Fig. 3. Specifications for livestock fences constructed

on antelope ranges, recommended by the US Bureau of Land

Management Regional Fencing Workshop (1974).

Pronghorns are social

animals, gathering in relatively large herds. In spring,

however, bucks are alone or form small groups.

Pronghorns breed during September and October. Bucks are

polygamous, collecting harems of 7 to 10 does, which

they defend from other bucks. Bucks and does begin

breeding at 15 to 16 months of age. Usually 2 kids

(young) are born 8 months after mating. The kids are

grayish brown at birth and usually weigh 5 to 7 pounds

(2.3 to 3.2 kg). Does nurse their kids and keep them

hidden until they are strong enough to join the herd,

usually at 3 weeks of age. By fall, the kids can take

care of themselves and are somewhat difficult to

distinguish from adults.

Pronghorns are relatively

disease- and parasite-free. Losses occur from predation,

primarily coyote, and starvation during severe winters

with prolonged deep snow.

Damage

Pronghorns sometimes cause

damage to grain fields, alfalfa, and haystacks during

the winter. Damage occurs from feeding, bedding, and

trampling.

Legal Status

Pronghorns have

game-animal status in all of the western states. Permits

are required to trap or shoot pronghorns.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Woven wire fences of 8-inch (20-cm) mesh, 48 inches

(1.2 m) high, near agricultural fields will help to

curtail damage. Electric fences with two wires spaced at

8 to 10 inches (20 to 25 cm) and 3 feet (90 cm) above

the ground will discourage pronghorns from entering

croplands. A single strand of electric wire painted with

molasses as an attractant and 30 to 36 inches (76 to 91

cm) above the ground will discourage pronghorn access.

Cultural Methods

Plant tall crops, such as corn, as a barrier between

rangelands and small grain fields to help reduce damage.

Alfalfa fields adjacent to rangeland are more vulnerable

and apt to suffer damage. Pronghorns often move out of

pastures that are heavily grazed by cattle to ungrazed

areas.

Frightening

Propane or acetylene exploders may provide temporary

relief from crop damage. These devices are also used for

bird damage control (see Bird Dispersal Techniques and

Supplies and Materials).

Repellents None are

registered.

Toxicants None are

registered, and poisoning pronghorns also violates state

laws that protect them as game animals.

Trapping

In areas where crop depredation and livestock

competition are severe, pronghorns can be readily herded

with aircraft into corral traps. After capture, they can

be translocated into suitable unoccupied habitat. This

technique is for use only by federal or state wildlife

agencies.

Shooting

Encourage legal hunting near agricultural fields to

help curtail crop damage. Shooting permits are available

in some states to remove pronghorns that are causing

significant damage outside of the regular hunting

season.

Economics of Damage and Control

Competition with livestock

and occasional damage to agricultural crops should be

weighed against the economic value of pronghorns as game

animals. Landowners in Texas and other Great Plains

states often charge $200 or more for trespass fees per

hunter. Guided hunts may yield $600 to $800 or more per

animal taken. In addition, many landowners derive

aesthetic pleasure from observing pronghorns. Some

states provide economic reimbursement for crop damage.

In Wyoming, costs of pronghorn crop damage on private

land, including administration (for example, salaries

and travel) averaged $169,453 per year (1987 to 1991).

Similar antelope crop damage costs in Colorado for the

same period averaged $5,510 per year.

Acknowledgments

Figure 1 by Charles W. Schwartz, adapted from

Yoakum (1978) by Emily Oseas Routman.

Figure 2 from Burt and

Grossenheider (1976), adapted by Jill Sack Johnson.

Figure 3 from the US

Bureau of Land Management (1974).

For Additional Information

Kitchen, D. W., and B. W. O’Gara. 1982. Pronghorn. Pages

960-971 in J. A. Chapman and G. A. Feldhamer, eds. Wild

mammals of North America: biology, management and

economics. The Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore,

Maryland.

O’Gara, B. W. 1978.

Antilocapra americana. Mammal. Sp. 90:1-7.

US Bureau of Land

Management. 1974. Proc. Regional Fencing Workshop.

Washington, DC. 74 pp.

Yoakum, J. D. 1978.

Pronghorn. Pages 102-122 in

J. L. Schmidt and D. L.

Gilbert, eds. Big game of North America. Wildl. Manage.

Inst. and Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Yoakum, J. D., and B. W.

O’Gara. 1992. Pronghorn antelope: ecology and

management. Wildl. Manage. Inst. (in prep).

Yoakum, J. D., and D. E.

Spalinger. 1979. American pronghorn antelope - articles

published in the Journal of Wildlife Management

1937-1977. The Wildl. Soc., Washington, DC. 244 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

D-74

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|