|

|

|

|

|

OTHER MAMMALS: Opossums |

|

|

Identification

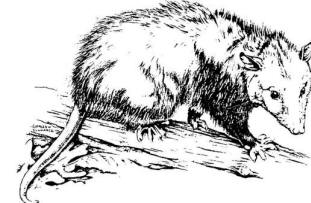

An opossum (Didelphis

virginiana) is a whitish or grayish mammal about the

size of a house cat (Fig. 1). Underfur is dense with

sparse guard hairs. Its face is long and pointed, its

ears rounded and hairless. Maximum length is 40 inches

(102 cm); the ratlike tail is slightly less than half

the total length. The tail may be unusually short in

northern opossums due to loss by frostbite. Opossums may

weigh as much as 14 pounds (6.3 kg); males average 6 to

7 pounds (2.7 to 3.2 kg) and females average 4 pounds

(6.3 kg). The skull is usually 3 to 4 inches (8 to 10

cm) long and contains 50 teeth — more than are found in

any other North

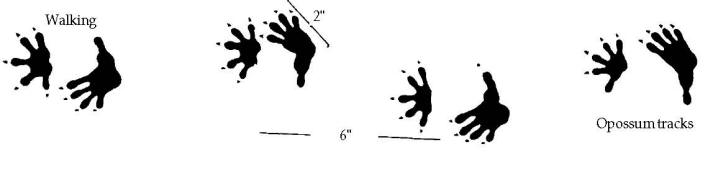

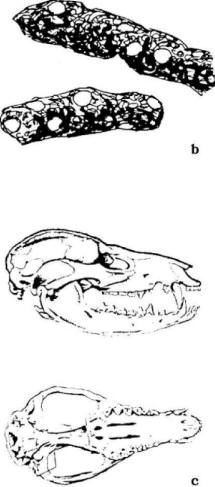

Fig. 2. Opossum sign and

characteristics: (a) tracks, (b) droppings, and (c)

skull.

American

mammal. Canine teeth (fangs) are prominent. Tracks of

both front and hind feet look as if they were made by

little hands with widely spread fingers (Fig. 2). They

may be distinguished from raccoon tracks, in which hind

prints appear to be made by little feet. The hind foot

of an opossum looks like a distorted hand. American

mammal. Canine teeth (fangs) are prominent. Tracks of

both front and hind feet look as if they were made by

little hands with widely spread fingers (Fig. 2). They

may be distinguished from raccoon tracks, in which hind

prints appear to be made by little feet. The hind foot

of an opossum looks like a distorted hand.

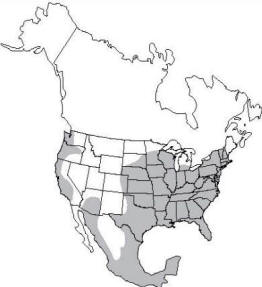

Fig. 3. Range of the

opossum in North America.

Range

Opossums are found in

eastern, central, and west coast states. Since 1900 they

have expanded their range northward in the eastern

United States. They are absent from the Rockies, most

western plains states, and parts of the northern United

States (Fig. 3).

Habitat

Habitats are diverse,

ranging from arid to moist, wooded to open fields.

Opossums prefer environments near streams or swamps.

They take shelter in burrows of other animals, tree

cavities, brush piles, and other cover. They sometimes

den in attics and garages where they may make a messy

nest.

Food Habits

Foods preferred by

opossums are animal matter, mainly insects or carrion.

Opossums also eat considerable amounts of vegetable

matter, especially fruits and grains. Opossums living

near people may visit compost piles, garbage cans, or

food dishes intended for dogs, cats, and other pets.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Opossums usually live

alone, having a home range of 10 to 50 acres (4 to 20

ha). Young appear to roam randomly until they find a

suitable home range. Usually they are active only at

night. The mating season is January to July in warmer

parts of the range but may start a month later and end a

month earlier in northern areas. Opossums may raise 2,

rarely 3, litters per year. The opossum is the only

marsupial in North America. Like other marsupials, the

blind, helpless young develop in a pouch. They are born

13 days after mating. The young, only 1/2 inch (1.3 cm)

long, find their way into the female’s pouch where they

each attach to one of 13 teats. An average of 7 young

are born. They remain in the pouch for 7 to 8 weeks. The

young remain with the mother another 6 to 7 weeks until

weaned.

Most young die during

their first year. Those surviving until spring will

breed in that first year. The maximum age in the wild is

about 7 years.

Although opossums have a

top running speed of only 7 miles per hour (11.3 km/hr),

they are well equipped to escape enemies. They readily

enter burrows and climb trees. When threatened, an

opossum may bare its teeth, growl, hiss, bite, screech,

and exude a smelly, greenish fluid from its anal glands.

If these defenses are not successful, an opossum may

play dead.

When captured or surprised

during daylight, opossums appear stupid and inhibited.

They are surprisingly intelligent, however. They rank

above dogs in some learning and discrimination tests.

Damage

Although opossums may be

considered desirable as game animals, certain

individuals may be a nuisance near homes where they may

get into garbage, bird feeders, or pet food. They may

also destroy poultry, game birds, and their nests.

Legal Status

Laws protecting opossums

vary from state to state. Usually there are open seasons

for hunting or trapping opossums. It is advisable to

contact local wildlife authorities before removing

nuisance animals.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Prevent nuisance animals

from entering structures by closing openings to cages

and pens that house poultry. Opossums can be prevented

from climbing over wire mesh fences by installing a

tightly stretched electric fence wire near the top of

the fence 3 inches (8 cm) out from the mesh. Fasten

garbage can lids with a rubber strap.

Traps

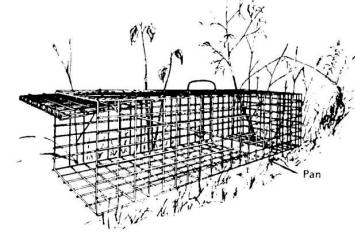

Opossums are not wary of

traps and may be easily caught with suitable-sized box

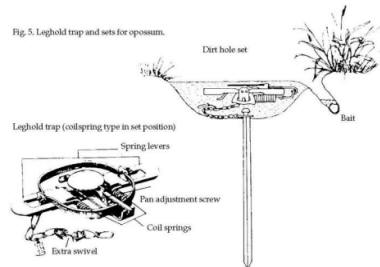

or cage traps (Fig. 4). No. 1 or 1 1/2 leghold traps

also are effective. Set traps along fences or

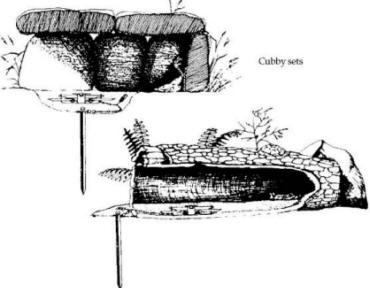

trail-ways. Dirt hole sets or cubby sets are effective

(Fig. 5). A dirt hole is about 3 inches (8 cm) in

diameter and 8 inches (20 cm) deep. It extends into the

earth at a 45 o angle. The trap should be set at the

entrance to the hole. A cubby is a small enclosure made

of rocks, logs, or a box. The trap is set at the

entrance to the cubby. The purpose of the dirt hole or

cubby is to position the animal so that it will place

its foot on the trap. Place bait such as cheese, or

slightly spoiled meat, fish, or fruit in the dirt hole

or cubby to attract the animal. Using fruit instead of

meat will reduce the chance of catching cats, dogs, or

skunks.

Fig. 4. Cage trap (set position).

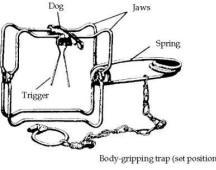

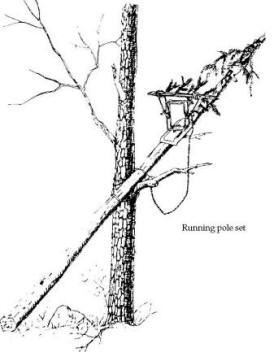

Fig. 6. Body-gripping trap

and running pole set.

A medium-sized

body-gripping (kill type) trap will catch and kill

opossums. Place bait behind the trap in such a way that

the animal must pass through the trap to get it.

Body-gripping traps kill the captured animal quickly. To

reduce chances of catching pets, set the trap above

ground on a running pole (Fig. 6).

Shooting

A rifle of almost any

caliber or a shotgun loaded with No. 6 shot or larger

will effectively kill opossums. Use a light to look for

opossums after dark. If an opossum has not been alarmed,

it will usually pause in the light long enough to allow

an easy shot. Once alarmed, opossums do not run rapidly.

They will usually climb a nearby tree where they can be

located with a light. Chase running opossums on foot or

with a dog. If you lose track, run to the last place

where you saw the animal. Stop and listen for the sound

of claws on bark to locate the tree the animal is

climbing.

Sometimes opossums can be

approached quietly and killed by a strong blow with a

club, but they can be surprisingly hard to kill in this

manner. They can be taken alive by firmly grasping the

end of the tail. If the animal begins to “climb its

tail” to reach your hand, lower the animal until it

touches the ground. This will distract the opossum and

cause it to try to escape by crawling. Opossums can

carry rabies, so wear heavy gloves and be wary of bites.

Euthanize unwanted animals

humanely with carbon dioxide gas, or release them

several miles from the point of capture.

Economics of Damage and Control

No data are available;

however, it is usually worthwhile to remove a particular

animal that is causing damage.

Acknowledgments

Much of the information on

habitat, food habits, and general biology comes from J.

J. McManus (1974) and A. L. Gardner (1982). The

manuscript was read and improved by Jim Byford and

Robert Timm.

Figures 1, 2a, 2c, and 3

from Schwartz and Schwartz (1981).

Figure 2b by Jill Sack

Johnson.

Figures 4, 5, and 6 by

Michael D. Stickney, from the New York Department of

Environmental Conservation publication “Trapping

Furbearers, Student Manual” (1980), by R. Howard, L.

Berchielli, C. Parsons, and M. Brown. The figures are

copyrighted and are used with permission.

For Additional Information

Fitch, H. S., and L. L.

Sandidge. 1953. Ecology of the opossum on a natural area

in northeastern Kansas. Univ. Kansas Publ. Museum Nat.

Hist. 7:305-338.

Gardner, A. L. 1982.

Virginia opossum. Pages 3-36 in J. A. Chapman and G. A.

Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North America: biology,

management, and economics. The Johns Hopkins Univ.

Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Hall, E. R., and K. R.

Kelson. 1959. The mammals of North America, Vol. 1.

Ronald Press Co., New York. 546 pp.

Hamilton, W. J., Jr. 1958.

Life history and economic relations of the opossum (Didelphis

marsupialis virginiana) in New York State. Cornell Univ.

Agric. Exp. Sta. Memoirs 354:1-48.

Howard, R., L. Berchielli,

C. Parsons, and M. Brown. 1980. Trapping furbearers,

student manual. State of New York, Dep. Environ. Conserv.

59 pp.

Lay, D. W. 1942. Ecology

of the opossum in eastern Texas. J. Mammal. 23:147-159.

McManus, J. J. 1974.

Didelphis virginiana. Mammal. Species 40:1-6.

Reynolds, H. C. 1945. Some

aspects of the life history and ecology of the opossum

in central Missouri. J. Mammal. 26:361-379.

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri, rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia, 356 pp.

Seidensticker, J., M. A.

O’Connell, and A. J. T. Johnsingh. 1987. Virginia

opossum. Pages 246-263 in M. Novak, J. A. Baker, M. E.

Obbard, and B. Malloch, eds. Wild furbearer management

and conservation in North America. Ontario Ministry Nat.

Resour. Toronto.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom, Robert

M. Timm, Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

D-64

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|