|

|

|

|

|

OTHER MAMMALS: Jack Rabbits and other

Hares |

|

|

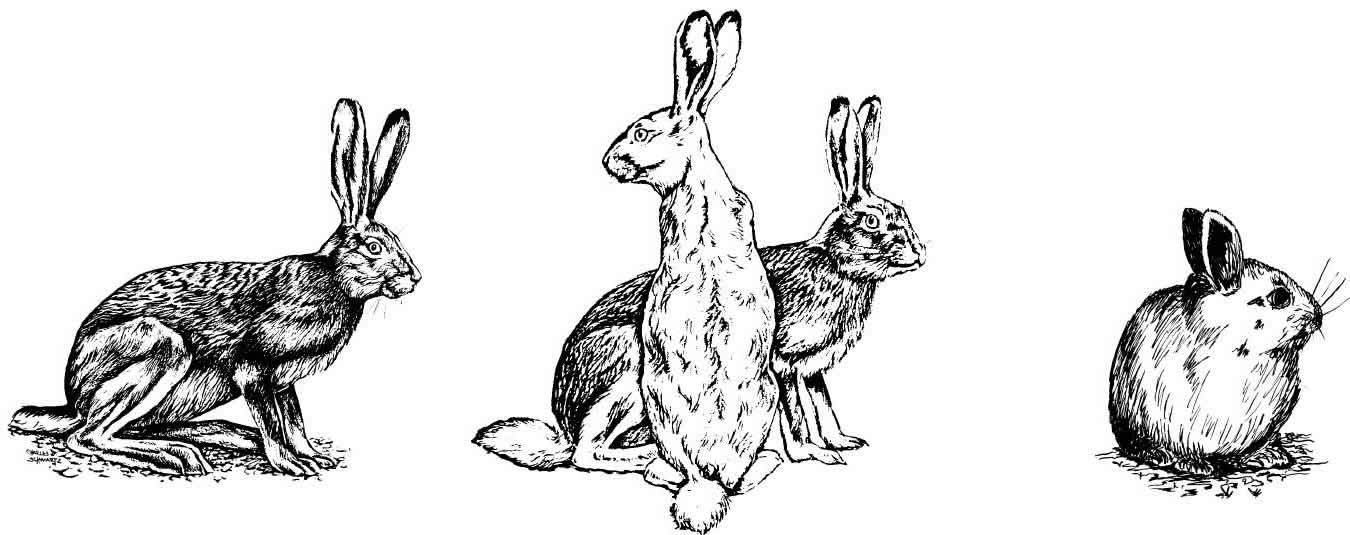

Fig. 1. Blacktail

jackrabbit, Lepus californicus (left); whitetail

jackrabbits, L. townsendii (middle); showshoe hare, L.

americanus (right).

Identification

Three major species of

jackrabbits occur in North America (Fig. 1). These hares

are of the genus Lepus and are represented primarily by

the blacktail jackrabbit, the whitetail jackrabbit, and

the snowshoe hare. Other members of this genus include

the antelope jackrabbit and the European hare. Hares

have large, long ears, long legs, and a larger body size

than rabbits.

The whitetail jackrabbit

is the largest hare in the Great Plains, having a head

and body length of 18 to 22 inches (46 to 56 cm) and

weighing 5 to 10 pounds (2.2 to4.5 kg). It is brownish

gray in summer and white or pale gray in winter. The

entire tail is white. The blacktail jackrabbit, somewhat

smaller than its northern cousin, weighs only 3 to 7

pounds (1.3 to 3.1 kg) and is 17 to 21 inches (43 to 53

cm) long. It has a grayish-brown body, large

black-tipped ears, and a black streak on the top of its

tail. The snowshoe hare is 13 to 18 inches (33 to 46 cm)

long and weighs 2 to 4 pounds (0.9 to 1.8 kg). It has

larger feet than the whitetail and blacktail

jackrabbits. The snowshoe turns white in winter and is a

dark brown during the summer. Its ears are smaller than

those of the other hares. The antelope jackrabbit is 19

to 21 inches (48 to 53 cm) long and weighs 6 to 13

pounds (2.7 to 5.9 kg). Its ears are extremely large and

its sides are a pale white. The European hare is the

largest of the hares in the Northeast, weighing 7 to 10

pounds (3.1 to 4.5 kg) and reaching 25 to 27 inches (63

to 68 cm) in size. This nonnative hare is brownish gray

year-round.

Range

The whitetail jackrabbit

is found mainly in the north central and northwestern

United States and no further south than the extreme

north central part of New Mexico and southern Kansas

(Fig. 2a).The blacktail jackrabbit is found mainly in

the southwestern United States and the southern Great

Plains, and no further north than central South Dakota

and southern Washington (Fig. 2b). Snowshoe hares occupy

the northern regions of North America, including Canada,

Alaska, the northern continental United States, and the

higher elevations as far south as New Mexico (Fig. 2c).

Antelope jackrabbits are found only in southern Arizona,

New Mexico, and western Mexico. The European hare is

found only in southern Quebec, New York, and other New

England states.

Fig. 2. Range of the (a)

whitetail jackrabbit, (b) blacktail jackrabbit, and (c)

snowshoe hare.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Members of the genus Lepus

are born well-furred and able to move about. Little or

no nest is prepared, although the young are kept hidden

for 3 to 4 days. Females may produce up to 4 litters per

year with 2 to 8 young per litter. Reproductive rates

may vary from year to year depending on environmental

conditions.

Where food and shelter are

available in one place, no major daily movement of hares

occurs. When food areas and shelter areas are separated,

morning and evening movements may be observed. Daily

movements of 1 to 2 miles (1.6 to 3.2 km) each way are

fairly common. In dry seasons, 10-mile (16-km) round

trips from desert to alfalfa fields have been reported.

Damage

Hares consume 1/2 to 1

pound (1.1 to 2.2 kg) of green vegetation each day.

Significant damage occurs when hare concentrations are

attracted to orchards, gardens, ornamentals, or other

agricultural crops. High jackrabbit populations can also

damage range vegetation.

Most damage to gardens,

landscapes, or agricultural crops occurs in areas

adjacent to swamps or rangeland normally used by hares.

Damage may be temporary and usually occurs when natural

vegetation is dry. Green vegetation may be severely

damaged during these dry periods.

Orchards and ornamental

trees and shrubs are usually damaged by overbrowsing,

girdling, and stripping of bark, especially by snowshoe

hares. This type of damage is most common during winter

in northern areas.

Rangeland overbrowsing and

overgrazing can occur any time jackrabbit numbers are

high. Eight jackrabbits are estimated to eat as much as

one sheep, and 41 jackrabbits as much as one cow.

Estimates of jackrabbit

populations run as high as 400 jackrabbits per square

mile (154/km 2) extending over several hundred square

miles. Range damage can be severe in such situations,

especially where vegetation productivity is low.

Legal Status

Jackrabbits are considered

nongame animals in most states and are not protected by

state game laws. A few states protect jackrabbits

through regulations. Most states in which snowshoe hares

occur have some regulations protecting them. Consult

local wildlife agencies to determine the legal status of

the species before applying controls.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Fencing. Exclusion is most often accomplished by the

construction of fences and gates around the area to be

protected. Woven wire or poultry netting should exclude

all hares from the area to be protected. To be

effective, use wire mesh of less than 1 1/2 inches (3.8

cm), 30 to 36 inches (76 to 91 cm) high, with at least

the bottom 6 inches (15 cm) buried below ground level.

Regular poultry netting made of 20gauge wire can provide

protection for 5 to 7 years or more. Although the

initial cost of fences appears high—about $1,000 per

mile ($625/km)—they are economically feasible for

protecting high-value crops and provide year-round

protection on farms with a history of jackrabbit

problems. Remember to spread the initial cost over the

expected life of the fence when comparing fencing with

other methods. Exclusion by fencing is desirable for

small areas of high-value crops such as gardens, but is

usually impractical and too expensive for larger

acreages of farmland.

Electric fencing has been

found to exclude jackrabbits. Six strands spaced 3

inches (7.6 cm) apart alternating hot and ground wires

should provide a deterrent to most hares. Modern

energizers and high-tensile wire will minimize cost and

maximize effectiveness.

Tree Trunk Guards. The use

of individual protectors to guard the trunks of young

trees or vines may also be considered a form of

exclusion. Among the best of these are cylinders made

from woven wire netting. Twelve- to 18-inch-wide

(30.5-to 45.7-cm) strips of 1-inch (2.5-cm) mesh poultry

netting can be formed into cylinders around trees.

Cylinders should be anchored with lath or steel rods and

braced away from the trunk to prevent rabbits from

pressing them against the trees and gnawing through

them.

Types of tree protectors

commercially available include aluminum, nylon mesh

wrapping, and treated jute cardboard. Aluminum foil, or

even ordinary sacking, has been wrapped and tied around

trees with effective results.

Wrapping the bases of

haystacks with 3-foot-high (0.9-m) poultry netting

provides excellent protection.

Cultural Methods

Habitat Manipulation. In areas where jackrabbit or

hare damage is likely to occur, highly preferred crops

such as alfalfa, young cotton plants, lettuce, and young

grape vines are usually most damaged. Crops with large

mature plants, such as corn, usually are not damaged

once they grow beyond the seedling stage. Where

possible, avoid planting vulnerable crops near

historically high hare populations.

Overuse of range forage

can sometimes lead to high jackrabbit numbers.

Jackrabbits are least abundant where grass grows best

within their range. Like many rodents, they prefer open

country with high visibility to areas where the grass

prevents them from seeing far. Thus, control programs

accompanied by changes in grazing practices that

encourage more vegetative growth may be necessary for

long-term relief.

Frightening

Guard Dogs. Dogs can be chained along boundaries of

crop fields or near gardens to deter jackrabbits.

Repellents

Since state pesticide registrations vary, check with

your local Cooperative Extension or USDA-APHIS-ADC

office for information on repellents legal in your area.

Various chemical

repellents are offered as a means of reducing or

preventing hare damage to trees, vines, or farm and

garden crops. Repellents make protected plants

distasteful to jackrabbits. A satisfactory repellent

must also be noninjurious to plants.

In the past, a variety of

repellents have been recommended in the form of paints,

smears, or sprays. Many of these afford only temporary

protection and must be reapplied too often to warrant

their use. Other, more persistent materials have caused

injurious effects to the treated plants. Some chemical

substances such as lime-sulphur, copper carbonate, and

asphalt emulsions have provided a certain amount of

protection and were harmless to the plants. These are

less commonly used today and have been replaced by

various commercial preparations such as ammonium soaps,

capsaicin, dried blood, napthalene, thiram, tobacco

dust, and ziram, which are probably more effective.

Repellents are applied during either the winter dormant

season or summer growing season. Recommendations vary

accordingly.

Be sure to use repellents

according to the manufacturer’s guidelines and follow

label recommendations.

Powders. Any repellent

applications that involve the use of powders should be

dusted on garden crops early in the morning when plants

are covered with dew, or immediately after a rain. Do

not touch plants with equipment or clothing because

moist plants, especially beans, are susceptible to

disease. When a duster is not available and only a few

plants are involved, use a bag made of cheesecloth to

sift repellent dust onto plant foliage. Repeated

applications may be necessary after rains have washed

the powder from the foliage and as new plant growth

takes place.

Sprays. Thoroughly cover

the upper surfaces of the leaves with spray repellent.

If a sprayer is unavailable and only a small number of

plants are involved, a whisk broom or brush can be used

to apply the repellent to the plant foliage. The

repellents will adhere to the foliage for a longer

period if a latex-type adhesive is used. Reapply liquid

repellents after a heavy rain and at 10-day intervals to

make certain new plant growth is protected.

Some repellents are

not registered for application to leaves, stems, or

fruits of plants to be harvested for human use. A list

of registered commercial repellents can be found in

Supplies and Materials. Many of these may be purchased

at a reasonable cost from suppliers handling seed,

insecticides, hardware, and farm equipment.

Commercial repellents

containing thiram are effective and can be applied

safely to trees and shrubs. Treat all stems and low

branches to a point higher than rabbits can reach while

standing on top of the estimated snow cover. One

application made during a warm, dry day in late fall

should suffice for the entire dormant season. Coal tar,

pine tar, tar paper, and oils have caused damage to

young trees under certain conditions. Carbolic acid and

other volatile compounds have proved effective for only

short periods. For further information on repellents and

their availability, see Supplies and Materials.

Toxicants

Since state pesticide registrations vary, check with

your local Cooperative Extension or USDA-APHIS-ADC

office for information on toxicants legal in your area.

Be sure to read the entire label. Use strictly in

accordance with precautionary statements and directions.

State and federal regulations also apply.

Anticoagulants. In areas

where they are legal, anticoagulant baits may be used to

control jackrabbits. Varying degrees of success have

been reported with diphacinone, warfarin, brodifacoum,

and bromadiolone. Anticoagulants control jackrabbits and

hares by reducing the clotting ability of the blood and

by causing damage to the capillary blood vessels. Death

is caused only if the treated bait is consumed in

sufficient quantities for several days. A single feeding

on anticoagulant baits will not control jackrabbits.

Brodifacoum and bromadiolone may be exceptions, but they

are not yet registered for use on jackrabbits. Bait must

be eaten at several feedings on 5 or more successive

days with no periods longer than 48 hours between

feedings.

When baiting with

anticoagulants, use covered self-dispensing feeders or

nursery flats to facilitate bait consumption and prevent

spillage. Secure feeding stations so that they cannot be

turned over. Place 1 to 5 pounds (0.5 to 2.5 kg) of bait

in a covered self-dispensing feeder or nursery flat in

runways, resting, or feeding areas that are frequented

by jackrabbits. Inspect bait stations daily and add bait

as needed. Acceptance may not occur until rabbits become

accustomed to the feeder stations or nursery flats,

which may take several days. When bait in the feeder is

entirely consumed overnight, increase the amount. It may

be necessary to move feeders to different locations to

achieve bait acceptance. Bait should be available until

all feeding ceases, which may take from 1 to 4 weeks.

Replace moldy or old bait with fresh bait. Pick up and

dispose of baits upon completion of control programs.

Dispose of poisoned rabbit carcasses by deep burying or

burning.

Fumigants There are

no fumigants registered for jackrabbits.

Trapping

Trapping with box-type traps is not effective

because jackrabbits are reluctant to enter a trap or

dark enclosure. Snowshoe hares are susceptible to

box-type traps.

Body-gripping and leghold

traps can be placed in rabbit runways. Trapping in

runways may result in unacceptable nontarget catches.

Check for tracks in snow or dirt surfaces to be sure

only target animals are present. Placement of sticks 1

foot (0.3 m) above the trap will encourage deer and

other large animals to step over the trap while allowing

access to jackrabbits or other hares. Be sure to check

with local wildlife officials on the legality of

trapping hares and jackrabbits.

Shooting

Where safe and legal to do so, shooting jackrabbits

may suppress or eliminate damage. Effective control may

be achieved using a spotlight and a shooter in the open

bed of a pickup truck. Driving around borders of crop

fields or within damaged range areas and carefully

shooting jackrabbits can remove a high percentage of the

population. Some states require permits to shoot from

vehicles or to use spotlights.

In some states sport

hunting of jackrabbits can be encouraged and may keep

populations below problem levels.

Other Methods Predators.

Natural enemies of jackrabbits include hawks, owls,

eagles, coyotes, bobcats, foxes, and weasels. Control of

these predators should occur only after taking into

account their beneficial effect on the reduction of

jackrabbit populations.

Economics of Damage and Control

Jackrabbits consume

considerable vegetation. In cases where their overuse of

natural forage results in the reduction of livestock on

rangeland, control measures may need to be implemented.

Few studies have been conducted on the

cost-effectiveness of jackrabbit control on rangelands.

Damage must be extreme to justify expenditures for

control programs. In most cases, cultural controls and

natural mortality will suffice to keep jackrabbit

populations in check.

Economic loss on croplands

is much easier to measure. In areas with historic

jackrabbit or hare damage, farmers should anticipate

problems and have materials available to use at the

first sign of damage. During dry times of the year or

times of natural food shortages, preventive measures

such as shooting and exclusion may be considered a part

of regular operations. Jackrabbits and other hares can

be deterred most easily if control measures are

implemented before the hares become accustomed to or

dependent on crops.

Acknowledgments

Figure 1 of the snowshoe

hare by Clint E. Chapman, University of Nebraska.

Figure 2 adapted by David

Thornhill, from Burt and Grossenheider (1976).

For Additional Information

Dunn, J. P., J. A. Chapman, and R. E. Marsh. 1982.

Jackrabbits. Pages 124-145 in J. A. Chapman and G. A.

Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North America: biology,

management, and economics. The Johns Hopkins Univ.

Press, Baltimore.

Evans, J., P. L. Hegdal,

and R. E. Griffith, Jr. 1982. Wire fencing for

controlling jackrabbit damage. Univ. Idaho. Coop. Ext.

Serv. Bull. No. 618. 7 pp.

Johnston, J. C. 1978.

Anticoagulant baiting for jackrabbit control. Proc.

Vertebr. Pest Conf. 8:152-153.

Lechleitner, R. R. 1958.

Movements, density, and mortality in a black-tailed

jackrabbit population. J. Wildl. Manage. 22:371-384.

Palmer, T. S. 1987.

Jackrabbits of the U.S. US Dep. Agric. Biol. Survey

Bull. 8:1-88

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri. Univ.

Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp.

Taylor W. P., C. T.

Vorhies, and P. B. Lister 1935. The relation of

jackrabbits to grazing in southern Arizona. J. For.

33:490-493.

US Department of the

Interior. 1973. Controlling rabbits. US Fish Wildl. Serv.

Bull. 2 pp.

Vorhies, C. T., and W. P.

Taylor. 1933. The life histories and ecology of

jackrabbits, Lepus alleni and Lepus californicus sp. in

relation to grazing in Arizona. Univ. Arizona Agric.

Exp. Stn. Tech. Bull. 49:467-587.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom; Robert

M. Timm; Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|