|

|

|

|

|

OTHER MAMMALS: Cottontail Rabbits |

|

|

Fig. 1. Eastern cottontail

rabbit, Sylvilagus floridanus

Introduction

Rabbits mean different

things to different people. For hunters, the cottontail

rabbit is an abundant, sporting, and tasty game animal.

However, vegetable and flower gardeners, farmers, and

homeowners who are suffering damage may have very little

to say in favor of cottontails. They can do considerable

damage to flowers, vegetables, trees, and shrubs any

time of the year and in places ranging from suburban

yards to rural fields and tree plantations. Control is

often necessary to reduce damage, but complete

extermination is not necessary, desirable, or even

possible.

Rabbits usually can be

accepted as interesting additions to the backyard or

rural landscape if control techniques are applied

correctly. Under some unusual circumstances, control of

damage may be difficult.

Damage control methods

include removal by live trapping or hunting, exclusion,

and chemical repellents. In general, no toxicants or

fumigants are registered for rabbit control; however,

state regulations may vary. Frightening devices may

provide a sense of security for the property owner, but

they rarely diminish rabbit damage.

Identification

There are 13 species of

cottontail rabbits (genus Sylvilagus), nine of which are

found in various sections of North America north of

Mexico. All nine are similar in general appearance and

behavior, but differ in size, range, and habitat. Such

differences result in a wide variation of damage

problems, or lack of problems. The pygmy rabbit (S.

idahoensis), found in the Pacific Northwest, weighs only

1 pound (0.4 kg), while the swamp rabbit (S. aquaticus),

found in the southeastern states as far north as

southern Illinois, may weigh up to 5 pounds (2.3 kg).

Most species prefer open, brushy, or cultivated areas

but some frequent marshes, swamps, or deserts. The swamp

rabbit and the marsh rabbit (S. palustris) are strong

swimmers. The eastern cottontail (S. floridanus) is the

most abundant and widespread species. For the purposes

of the discussion here about damage control and biology,

the eastern cottontail (Fig. 1) will be considered

representative of the genus. Cottontail rabbits must be

distinguished from jackrabbits and other hares, which

are generally larger in size and have longer ears.

Jackrabbits are discussed in another chapter of this

book.

The eastern cottontail

rabbit is approximately 15 to 19 inches (37 to 48 cm) in

length and weighs 2 to 4 pounds (0.9 to 1.8 kg). Males

and females are basically the same size and color.

Cottontails appear gray or brownish gray in the field.

Closer examination reveals a grizzled blend of white,

gray, brown, and black guard hairs over a soft grayish

or brownish underfur, with a characteristic rusty brown

spot on the nape of the neck. Rabbits molt twice each

year, but remain the same general color. They have large

ears, though smaller than those of jackrabbits, and the

hind feet are much larger than the forefeet. The tail is

short and white on the undersurface, and its similarity

to a cotton ball resulted in the rabbits common name.

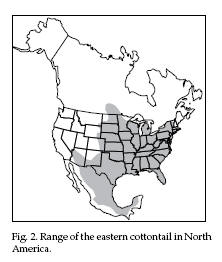

Range Range

The eastern cottontail's

range includes the entire United States east of the

Rocky Mountains and introductions further west. It

extends from southern New England along the Canadian

border west to eastern Montana and south into Mexico and

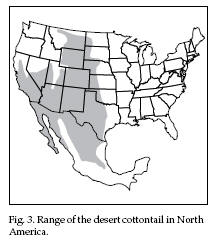

South America (Fig. 2). The most common species of the

western United States include the desert cottontail (S.

auduboni, Fig. 3), and mountain cottontail (S. muttalli,

Fig. 4). Refer to a field guide or suggested readings if

other species of the genus Sylvilagus are of interest.

Habitat

Cottontails do not

distribute themselves evenly across the landscape. They

tend to concentrate in favorable habitat such as brushy

fence rows or field edges, gullies filled with debris,

brush piles, or landscaped backyards where food and

cover are suitable. They are rarely found in dense

forests or open grasslands, but fallow crop fields, such

as those in the Conservation Reserve Program, may

provide suitable habitat.

Cottontails

generally spend their entire lives in an area of 10

acres or less. Occasionally they may move a mile or so

from summer range to winter cover or to a new food

supply. Lack of food or cover is usually the motivation

for a rabbit to relocate. In suburban areas, rabbits are

numerous and mobile enough to fill any habitat created

when other rabbits are removed. Population density

varies with habitat quality, but one rabbit per acre is

a reasonable average. Cottontails

generally spend their entire lives in an area of 10

acres or less. Occasionally they may move a mile or so

from summer range to winter cover or to a new food

supply. Lack of food or cover is usually the motivation

for a rabbit to relocate. In suburban areas, rabbits are

numerous and mobile enough to fill any habitat created

when other rabbits are removed. Population density

varies with habitat quality, but one rabbit per acre is

a reasonable average.

Contrary to popular

belief, cottontails do not dig their own burrows, as the

European rabbit does. Cottontails use natural cavities

or burrows excavated by woodchucks or other animals.

Underground dens are used

primarily in extremely cold or wet weather and to escape

pursuit. Brush piles and other areas of cover are often

adequate alternatives to burrows.

In spring and fall,

rabbits use a grass or weed shelter. The form is a

nestlike cavity on the surface of the ground, usually

made in dense cover. It gives the rabbit some protection

from weather, but is largely used for concealment. In

summer, lush green growth provides both food and

shelter, so there is little need for a form.

General Biology and Reproduction

Rabbits

live only 12 to 15 months, and probably only one rabbit

in 100 lives to see its third fall, yet they make the

most of the time available to them. Cottontails can

raise as many as 6 litters in a year. Typically, there

are 2 to 3 litters per year in northern parts of the

cottontail range and up to 5 to 6 in southern areas. In

the north (Wisconsin), first litters are born as early

as late March or April. In the south (Texas), litters

may be born year-round. Litter size also varies with

latitude; rabbits produce 5 to 6 young per litter in the

north, 2 to 3 in the south. The rabbit's gestation

period is only 28 or 29 days, and a female is usually

bred again within a few hours of giving birth. Rabbits

give birth in a shallow nest depression in the ground.

Young cottontails are born nearly furless with their

eyes closed. Their eyes open in 7 to 8 days, and they

leave the nest in 2 to 3 weeks. Rabbits

live only 12 to 15 months, and probably only one rabbit

in 100 lives to see its third fall, yet they make the

most of the time available to them. Cottontails can

raise as many as 6 litters in a year. Typically, there

are 2 to 3 litters per year in northern parts of the

cottontail range and up to 5 to 6 in southern areas. In

the north (Wisconsin), first litters are born as early

as late March or April. In the south (Texas), litters

may be born year-round. Litter size also varies with

latitude; rabbits produce 5 to 6 young per litter in the

north, 2 to 3 in the south. The rabbit's gestation

period is only 28 or 29 days, and a female is usually

bred again within a few hours of giving birth. Rabbits

give birth in a shallow nest depression in the ground.

Young cottontails are born nearly furless with their

eyes closed. Their eyes open in 7 to 8 days, and they

leave the nest in 2 to 3 weeks.

Under good conditions,

each pair of rabbits could produce approximately 18

young during the breeding season. Fortunately, this

potential is rarely reached. Weather, disease,

predators, encounters with cars and hunters, and other

mortality factors combine to keep a lid on the rabbit

population.

Because of the cottontails

reproductive potential, no lethal control is effective

for more than a limited period. Control measures are

most effective when used against the breeding population

during the winter. Habitat modification and exclusion

techniques provide long-term, nonlethal control.

Food Habits, Damage, and Damage Identification

The appetite of a rabbit

can cause problems every season of the year. Rabbits eat

flowers and vegetables in spring and summer. In fall and

winter, they damage and kill valuable woody plants.

Rabbits will devour a wide

variety of flowers. The one most commonly damaged is the

tulip; they especially like the first shoots that appear

in early spring.

The proverbial carrot

certainly is not the only vegetable that cottontails

eat. Anyone who has had a row of peas, beans, or beets

pruned to ground level knows how rabbits like these

plants. Only a few crops, corn, squash, cucumbers,

tomatoes, potatoes, and some peppers seem to be immune

from rabbit problems.

Equally annoying, and much

more serious, is the damage rabbits do to woody plants

by gnawing bark or clipping off branches, stems, and

buds. In winter in northern states, when the ground is

covered with snow for long periods, rabbits often

severely damage expensive home landscape plants,

orchards, forest plantations, and park trees and shrubs.

Some young plants are clipped off at snow height, and

large trees and shrubs may be completely girdled. When

the latter happens, only sprouting from beneath the

damage or a delicate bridge graft around the damage will

save the plant.

A rabbit's tastes in food

can vary considerably by region and season. In general,

cottontails seem to prefer plants of the rose family.

Apple trees, black and red raspberries, and blackberries

are the most frequently damaged food-producing woody

plants, although cherry, plum, and nut trees are also

damaged.

Among shade and ornamental

trees, the hardest hit are mountain ash, basswood, red

maple, sugar maple, honey locust, ironwood, red and

white oak, and willow. Sumac, rose, Japanese barberry,

dogwood, and some woody members of the pea family are

among the shrubs damaged. Evergreens seem to be more

susceptible to rabbit damage in some areas than in

others. Young trees may be clipped off, and older trees

may be deformed or killed.

The character of the bark

on woody plants also influences rabbit browsing. Most

young trees have smooth, thin bark with green food

material just beneath it. Such bark provides an

easy-to-get food source for rabbits. The thick, rough

bark of older trees often discourages gnawing. Even on

the same plant, rabbits avoid the rough bark but girdle

the young sprouts that have smooth bark.

Rabbit damage can be

identified by the characteristic appearance of gnawing

on older woody growth and the clean-cut, angled clipping

of young stems. Distinctive round droppings in the

immediate area are a good sign of their presence too.

Rabbit damage rarely

reaches economic significance in commercial fields or

plantations, but there are exceptions. For example,

marsh rabbits have been implicated in sugarcane damage

in Florida. Growers should always be alert to the

potential problems caused by locally high rabbit

populations.

Legal Status

In most states, rabbits

are classified as game animals and are protected as such

at all times except during the legal hunting season.

Some state regulations may grant exceptions to property

owners, allowing them to trap or shoot rabbits outside

the normal hunting season on their own property.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

One of the best ways to

protect a backyard garden or berry patch is to put up a

fence. It does not have to be tall or especially sturdy.

A fence of 2-foot (60cm) chicken wire with the bottom

tight to the ground or buried a few inches is

sufficient. Be sure the mesh is 1 inch

(2.5

cm) or smaller so that young rabbits will not be able to

go through it. A more substantial fence of welded wire,

chain link, or hog wire will keep rabbits, pets, and

children out of the garden and can be used to trellis

vine crops. The lower 1 1/2 to 2 feet (45 to 60 cm)

should be covered with small mesh wire. A fence may seem

costly, but with proper care it will last many years and

provide relief from the constant aggravation of rabbit

damage. Inexpensive chicken wire can be replaced every

few years. (2.5

cm) or smaller so that young rabbits will not be able to

go through it. A more substantial fence of welded wire,

chain link, or hog wire will keep rabbits, pets, and

children out of the garden and can be used to trellis

vine crops. The lower 1 1/2 to 2 feet (45 to 60 cm)

should be covered with small mesh wire. A fence may seem

costly, but with proper care it will last many years and

provide relief from the constant aggravation of rabbit

damage. Inexpensive chicken wire can be replaced every

few years.

Cylinders of 1/4-inch

(0.6-cm) wire hardware cloth will protect valuable young

orchard trees or landscape plants (Fig. 5). The

cylinders should extend higher than a rabbits reach

while standing on the expected snow depth, and stand 1

to 2 inches (2.5 to 5 cm) out from the tree trunk.

Larger mesh sizes, 1/2- to 3/4-inch (1.2-to 1.8-cm), can

be used to reduce cost, but be sure the cylinder stands

far enough away from the tree trunk that rabbits cannot

eat through the holes. Commercial tree guards or tree

wrap are another alternative. Several types of paper

wrap are available, but they are designed for protection

from sun or other damage. Check with your local garden

center for advice. When rabbits are abundant and food is

in short supply, only hardware cloth will guarantee

protection. Small mesh (1/4-inch [0.6-cm]) hardware

cloth also protects against mouse damage.

A dome or cage of chicken

wire secured over a small flower bed will allow

vulnerable plants such as tulips to get a good start

before they are left unprotected.

Habitat Modification

One form of natural

control is manipulation of the rabbits habitat. Although

frequently overlooked, removing brush piles, weed

patches, dumps, stone piles, and other debris where

rabbits live and hide can be an excellent way to manage

rabbits. It is especially effective in suburban areas

where fewer suitable habitats are likely to be

available. Vegetation control along ditch banks or fence

rows will eliminate rabbit habitat in agricultural

settings but is likely to have detrimental effects on

other species such as pheasants. Always weigh the

consequences before carrying out any form of habitat

management.

Repellents

Several chemical

repellents discourage rabbit browsing. Always follow

exactly the directions for application on the container.

Remember that some repellents are poisonous and require

safe storage and use. For best results, use repellents

and other damage control methods at the first sign of

damage.

Most repellents can be

applied, like paint, with a brush or sprayer. Many

commercially available repellents contain the fungicide

thiram and can be purchased in a ready-to-use form (see

Supplies and Materials).

Some formerly recommended

repellents are no longer available. Most repellents are

not designed to be used on plants or plant parts

destined for human consumption. Most rabbit repellents

are contact or taste repellents that render the treated

plant parts distasteful. Mothballs are an example of an

area or odor repellent that repels by creating a noxious

odor around the plants to be protected. Taste repellents

protect only the parts of the plant they contact; new

growth that emerges after application is not protected.

Heavy rains may necessitate reapplication of some

repellents.

Mothballs or dried blood

meal sometimes keeps rabbits from damaging small flower

beds or garden plots. Place these substances among the

plants. Blood meal does not weather well, however.

Taste repellents are

usually more effective than odor repellents. The degree

of efficacy, however, is highly variable, depending on

the behavior and number of rabbits, and alternative

foods available. When rabbits are abundant and hungry,

use other control techniques along with chemical

repellents.

Toxicants

There are no toxicants or fumigants registered for use

against rabbits. Poisoning rabbits is not recommended.

Since state pesticide registrations vary, check with

your local Cooperative Extension Service or

USDA-APHIS-ADC office for information on repellents or

other new products available for use in your area.

Trapping

Trapping is the best way to remove rabbits in

cities, parks, and suburban areas. The first step is to

get a well built and well-designed live trap. Several

excellent styles of commercial live traps are available

from garden centers, hardware stores, and seed catalogs.

Most commercial traps are wire and last indefinitely

with proper care. Average cost is about $20 to $30. Live

traps can often be rented from animal control offices or

pest control companies. An effective wooden box trap

(Fig. 6) can be made. This type of trap has proven

itself in the field and has been used in rabbit research

by biologists. For best results, follow the plan to the

letter because each detail has been carefully worked

out. Place traps where you know rabbits feed or rest.

Keep traps near cover that rabbits won't have to cross

large open areas to get to them. In winter, face traps

away from prevailing winds to keep snow and dry leaves

from plugging the entrance or interfering with the door.

Check traps daily to replenish bait or remove the

catches daily checks are essential for effective control

and for humane treatment of the animals. Move traps if

they fail to make a catch within a week.

Finding bait is not a

problem, even in winter, because cob corn (dry ear corn)

or dried apples make very good bait. Impale the bait on

the nail or simply position it at the rear of the trap

(commercial traps may not have a nail). When using cob

corn, use half a cob and push the nail into the pith of

the cob; this keeps the cob off the floor and visible

from the open door. Dried leafy alfalfa and clover are

also good cold weather baits.

Apples, carrots, cabbage,

and other fresh green vegetables are good baits in

warmer weather or climates. These soft baits become

mushy and ineffective once frozen. A good summer bait

for garden traps is a cabbage leaf rolled tightly and

held together by a toothpick. For best results, use

baits that are similar to what the target rabbits are

feeding on.

A commercial wire trap can

be made more effective (especially in winter) by

covering it with canvas or some other dark material. Be

sure the cover does not interfere with the trap’s

mechanism.

Release rabbits in rural

areas several miles from where they have been trapped if

local regulations allow relocation. Do not release them

where they may create a problem for someone else.

Shooting

Shooting is a quick, easy, and effective method of

control, but make sure that local firearms laws allow it

and that it is done safely. In some states, the owner or

occupant of a parcel of land may hunt rabbits all year

on that land, except for a short time before the firearm

deer season. Consult your state wildlife agency for

regulations. You must be persistent if shooting is the

only technique you rely on. Removing rabbits in one year

never guarantees that the rabbit population will be low

the next year (this is also true for trapping).

Other Methods

Encouraging the rabbits natural enemies or at least

not interfering with them may aid in reducing rabbit

damage. Hawks, owls, foxes, mink, weasels, and snakes

all help the farmer, gardener, homeowner, and forester

control rabbits. These animals should never be

needlessly destroyed. In fact, it is against the law to

kill hawks and owls; foxes, mink, and weasels are

protected during certain seasons as valuable furbearers.

Even the family cat can be a very effective predator on

young nestling rabbits, but cats are likely to kill

other wildlife as well.

Many people have a

favorite rabbit remedy. A piece of rubber hose on the

ground may look enough like a snake to scare rabbits

away. Another remedy calls for placing large, clear

glass jars of water in a garden. Supposedly, rabbits are

terrified by their distorted reflections. Most home

remedies, unfortunately, are not very effective.

Inflatable owls and snakes, eyespot balloons, and other

commercial products are readily available in garden

centers and through mail order catalogues. Feeding

rabbits during the winter in much the same way as

feeding wild birds might divert their attention from

trees and shrubs and thus reduce damage in some areas.

There is always the risk that this tactic can backfire

by drawing in greater numbers of rabbits or increasing

the survival of those present.

Acknowledgments

I thank R. A. McCabe for

reviewing this manuscript and providing the trap design.

Figure 1 from Schwartz and

Schwartz (1981).

Figures 2 and 3 adapted

from Burt and Grossenheider (1976) by Dave Thornhill,

University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Figures 4 and 5 courtesy

of the Department of Agricultural Journalism, University

of Wisconsin-Madison.

For Additional Information

Burt, W. H., and R. P.

Grossenheider. 1976. A field guide to the mammals, 3d

ed. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. 289 pp.

Chapman, J. A., J. G.

Hockman, and W. R. Edwards. 1982. Cottontails. Pages

83-123 in J. A. Chapman and G. A. Feldhamer, eds. Wild

mammals of North America: biology, management and

economics. The Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore.

Chapman, J. A., J. G.

Hockman, and Magaly M. Ojeda C. 1980. Sylvilagus

floridanus. Mammal. Sp. 136:1-8.

Jackson, H. H. T. 1961.

The mammals of Wisconsin. Univ. Wisconsin Press,

Madison. 504 pp.

McDonald, D. 1984.

Lagomorphs. Pages 714-721 in D. McDonald, ed. The

encyclopedia of mammals. Facts on File Publications, New

York.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom; Robert

M. Timm; Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994 Cooperative Extension Division

Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

01/25/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|