|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: Wolves |

|

|

Fig. 1. Adult gray wolf,

Canis lupus

Identification

Two species of wolves

occur in North America, gray wolves (Canis lupus) and

red wolves (Canis rufus). The common names are

misleading since individuals of both species vary in

color from grizzled gray to rusty brown to black. Some

gray wolves are even white. The largest subspecies of

the gray wolf are found in Alaska and the Northwest

Territories of Canada. Adult male gray wolves typically

weigh 80 to 120 pounds (36.3 to 54.4 kg), and adult

females 70 to 90 pounds

(31.8 to 40.8 kg).

Although males rarely exceed 120 pounds (54.4 kg), and

females 100 pounds (45.4 kg), some individuals may weigh

much more. Gray wolves vary in length from about 4.5 to

6.5 feet (1.4 to 2 m) from nose to tip of tail and stand

26 to 36 inches (66 to 91.4 cm) high at the shoulders (Mech

1970).

Red wolves are

intermediate in size between gray wolves and coyotes.

Typical red wolves weigh 45 to 65 pounds (20.4 to 29.5

kg). Total length ranges from about 4.4 to 5.4 feet (1.3

to 1.6 m) (Paradiso and Nowak 1972).

Wherever wolves occur,

their howls may be heard. The howl of a wolf carries for

miles on a still night. Both gray wolves and red wolves

respond to loud imitations of their howl or to sirens.

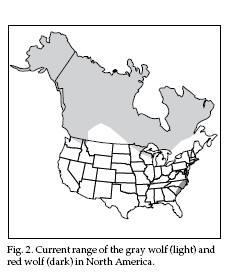

Range

During the 1800s, gray

wolves ranged over the North American continent as far

south as central Mexico. They did not inhabit the

southeastern states, extreme western California, or far

western Mexico (Young and Goldman 1944). In the late

1800s and early 1900s, wolves were eliminated from most

regions of the contiguous United States by control

programs that incorporated shooting, trapping, and

poisoning. Today, an estimated 55,000 gray wolves exist

in Canada and 5,900 to 7,200 in Alaska. In the

contiguous United States, the distribution of the gray

wolf has been reduced to approximately 3% of its

original range.

Minnesota

has the largest population of wolves in the lower 48

states, estimated at 1,550 to 1,750. A population of

wolves exists on Isle Royale in Lake Superior, but the

population is at an all-time low of 12 animals. In

recent years, wolves have recolonized Wisconsin, the

Upper Peninsula of Michigan, northwestern Montana,

central and northern Idaho, and northern Washington. A

few isolated gray wolves may also exist in remote areas

of Mexico. Minnesota

has the largest population of wolves in the lower 48

states, estimated at 1,550 to 1,750. A population of

wolves exists on Isle Royale in Lake Superior, but the

population is at an all-time low of 12 animals. In

recent years, wolves have recolonized Wisconsin, the

Upper Peninsula of Michigan, northwestern Montana,

central and northern Idaho, and northern Washington. A

few isolated gray wolves may also exist in remote areas

of Mexico.

Current efforts to

reestablish gray wolves are being conducted in

northwestern Montana, central Idaho, the Greater

Yellowstone area, and northern Washington (USFWS 1987).

Recovery through natural recolonization is likely in

northwestern Montana, central Idaho, and northern

Washington. Due to Greater Yellowstone’s geographic

isolation from areas with established wolf populations,

recovery there would likely require the reintroduction

of wolves into Yellowstone National Park.

Red wolves originally

occurred from central Texas to Florida and north to the

Carolinas, Kentucky, southern Illinois, and southern

Missouri (Young and Goldman 1944). Years of predator

control and habitat conversion had, by 1970, reduced the

range of the red wolf to coastal areas of southeastern

Texas and possibly southwestern Louisiana. When red wolf

populations became low, interbreeding with coyotes

became a serious problem. In the mid1970s, biologists

captured the last few red wolves for captive breeding

before the species was lost to hybridization. The red

wolf was considered extinct in the wild until 1987, when

reintroductions began.

Red wolf recovery attempts

have been made on Bulls Island near Charleston, South

Carolina, and on Alligator River National Wildlife

Refuge in eastern North Carolina (Phillips and Parker

1988). The Great Smoky Mountains National Park in

western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee is also

being considered as a red wolf reintroduction area. The

goal of the red wolf recovery plan is to return red

wolves to nonendangered status by “re-establishment of

self-sustaining wild populations in at least 2 locations

within the species’ historic range” (Abraham et al.

1980:14).

Habitat

Gray wolves occupy boreal

forests and forest/agricultural edge communities in

Minnesota, northern Wisconsin, and northern Michigan. In

northwest Montana, northern Idaho, and northern

Washington, wolves inhabit forested areas. In Canada and

Alaska, wolves inhabit forested regions and alpine and

arctic tundra. In Mexico, gray wolves are limited to

remote forested areas in the Sierra Madre Occidental

Mountains.

The last areas inhabited

by red wolves were coastal prairie and coastal marshes

of southeastern Texas and possibly southwestern

Louisiana. These habitats differ markedly from the

diverse forested habitats found over most of the

historic range of red wolves.

Food Habits

Mech (1970) reported that

gray wolves prey mainly on large animals including

white-tailed deer, mule deer, moose, caribou, elk, Dall

sheep, bighorn sheep, and beaver. Small mammals and

carrion make up the balance of their diet. During the

1800s, gray wolves on the Great Plains preyed mostly on

bison. As bison were eliminated and livestock husbandry

established, wolves commonly killed livestock.

Red wolves in southern

Texas fed primarily on small animals such as nutria,

rabbits, muskrats, and cotton rats (Shaw 1975). Carrion,

wild hogs, calves, and other small domestic animals were

also common food items.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Gray wolves are highly

social, often living in packs of two to eight or more

individuals. A pack consists of an adult breeding pair,

young of the year, and offspring one or more years old

from previous litters that remain with the pack. The

pack structure of gray wolves increases the efficiency

of wolves in killing large prey. Red wolves may be less

social than gray wolves, although red wolves appear to

maintain a group social structure throughout the year.

Each wolf pack has a home

range or territory that it defends against intruding

wolves. Packs maintain their territories by scent

marking and howling. On the tundra, packs of gray wolves

may have home ranges approaching 1,200 square miles

(3,108 km2). In forested areas, ranges are much smaller,

encompassing 40 to 120 square miles (104 to 311 km2).

Some wolves leave their pack and territory and become

lone wolves, drifting around until they find a mate and

a vacant area in which to start their own pack, or

wandering over large areas without settling. Extreme

movements, of 180 to 551 miles (290 to 886 km), have

been reported. These movements were probably of

dispersing wolves. The home ranges of red wolves are

generally smaller than those of gray wolves. Red wolf

home ranges averaged 27.3 square miles (71 km2) in

southern Texas (Shaw 1975).

Wild gray wolves usually

are sexually mature at 22 months of age. Breeding

usually takes place from early February through March,

although it has been reported as early as January and as

late as April. Pups are born 60 to 63 days after

conception, usually during April or May. Most litters

contain 4 to 7 young.

Courtship is an intimate

part of social life in the pack. Mating usually occurs

only between the dominant (alpha) male and female of the

pack. Thus, only 1 litter will be produced by a pack

during a breeding season. All pack members aid in

rearing the pups.

Dominance is established

within days after gray wolf pups are born. As pups

mature, they may disperse or maintain close social

contact with parents and other relatives and remain

members of the pack.

Little is known about

reproduction in red wolves, but it appears to be similar

to that of gray wolves. Red wolves may breed from late

December to early March. Usually 6 to 8 pups are

produced.

Damage and Damage Identification

The ability of wolves to

kill cattle, sheep, poultry, and other livestock is well

documented (Young and Goldman 1944, Carbyn 1983, Fritts

et al. 1992). From 1975 through 1986 an average of 21

farms out of 7,200 (with livestock) in the Minnesota

wolf range suffered verified losses annually to wolves (Fritts

et al. 1992). In more recent years, 50 to 60 farms

annually have been affected by wolf depredations in

Minnesota. Domestic dogs and cats are also occasionally

killed and eaten by gray wolves.

In many instances, wolves

live around livestock without causing damage or causing

only occasional damage. In other instances, wolves prey

on livestock and cause significant, chronic losses at

individual operations. In Minnesota, wolf depredation on

livestock is seasonal, most losses occurring between

April and October, when livestock are on summer

pastures. Livestock are confined to barnyards in the

winter months, and therefore are less susceptible to

predation.

Cattle, especially calves,

are the most common livestock taken. Wolves are capable

of killing adult cattle but seem less inclined to do so

if calves are available. Attacks usually involve only

one or two cattle per event. Depredation on sheep or

poultry often involves surplus killing. In Minnesota,

wolf attacks on sheep may leave several (up to 35)

individuals killed or injured per night. Attacks on

flocks of domestic turkeys in Minnesota have resulted in

nightly losses of 50 to 200 turkeys.

Wolf attacks on livestock

are similar to attacks on wild ungulates. A wolf chases

its prey, lunging and biting at the hindquarters and

flanks. Attacks on large calves, adult cattle, or horses

are characterized by bites and large ragged wounds on

the hindquarters, flanks, and sometimes the upper

shoulders (Roy and Dorrance 1976). When the prey is

badly wounded and falls, a wolf will try to disembowel

the animal. Attacks on young calves or sheep are

characterized by bites on the throat, head, neck, back,

or hind legs.

Wolves usually begin

feeding on livestock by eating the viscera and

hindquarters. Much of the carcass may be eaten, and

large bones chewed and broken. The carcass is usually

torn apart and scattered with subsequent feedings. A

wolf can eat 18 to 20 pounds (8.1 to 9 kg) of meat in a

short period. Large livestock killed by wolves are

consumed at the kill site. Smaller livestock may be

consumed at the kill site in one or two nights or they

may be carried or dragged a short distance from the kill

site. Wolves may carry parts of livestock carcasses back

to a den or rendezvous sites. Wolves may also carry off

and bury parts of carcasses.

Wolves and coyotes may

show similar killing and feeding patterns on small

livestock. Where the livestock has been bitten in the

throat, the area should be skinned out so that the size

and spacing of the tooth holes can be examined. The

canine tooth holes of a wolf are about 1/4 inch (0.6 cm)

in diameter while those of a coyote are about 1/8 inch

(0.3 cm) in diameter. Wolves usually do not readjust

their grip in the throat area as coyotes sometimes do;

thus, a single set of large tooth holes in the throat

area is typical of wolf depredation. Coyotes will more

often leave multiple tooth holes in the throat area.

Attacks on livestock by

dogs may be confused with wolf depredation if large

tracks are present, especially in more populated areas.

Large dogs usually injure and kill many animals. Some

dogs may have a very precise technique of killing, but

most leave several mutilated livestock. Unless they are

feral, they seldom feed on the livestock they have

killed.

Wolves are attracted to

and will scavenge the remains of livestock that have

died of natural causes. Dead livestock in a pasture or

on range land will attract wolves and increase their

activity in an area. It is important to distinguish

between predation and scavenging. Evidence of predation

includes signs of a struggle and hemorrhaging beneath

the skin in the throat, neck, back, or hindquarter area.

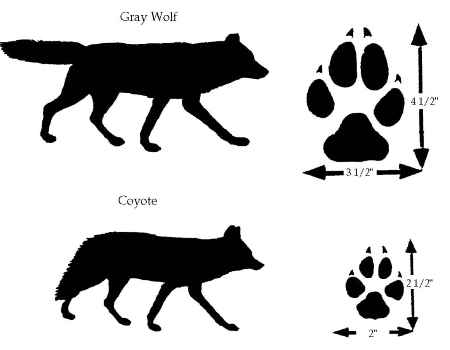

Tracks left by wolves at

kill sites are easily distinguishable from those of most

other predators except large dogs. Wolf tracks are

similar to coyote tracks but are much larger and reveal

a longer stride. A wolf’s front foot is broader and

usually slightly longer than its rear foot. The front

foot of the Alaskan subspecies is 4 to 5 inches (10.2 to

12.7 cm) long (without claws) and 3 3/4 to 5 inches (9.5

to 12.7 cm) wide; the rear foot is 3 3/4 to 4 3/4 inches

(9.5 to 12.1 cm) long and 3 to 4 1/2 inches (7.6 to 11.4

cm) wide (Murie 1954) (Fig. 3). Track measurements of

the eastern subspecies of gray wolf found in Minnesota

and Wisconsin are slightly smaller. The distance between

rear and front foot tracks of a wolf walking or trotting

on level ground varies between 25 and 38 inches (63.5 to

96.5 cm). When walking, wolves usually leave tracks in a

straight line, with the rear foot prints overlapping the

front foot prints. In deep snow, wolves exhibit a

single-file pattern of tracks, with following wolves

stepping in the tracks of the leading wolf.

Fig. 3. Gray wolf and coyote silhouettes and track

measurements of each.

Wolf tracks are similar to

the tracks of some large breeds of dogs but are

generally larger and more elongated, with broader toe

pads and a larger heel pad. Dog tracks are rounder than

wolf tracks, and the stride is shorter. When walking,

dogs leave a pattern of tracks that looks

straddle-legged, with the rear prints tending not to

overlap the front prints. Their tracks appear to wander,

in contrast to the straight-line pattern of wolf tracks.

Scats (droppings) left in

the vicinity of a kill site or pasture may be useful in

determining wolf depredation. Wolf scats are usually

wider and longer than coyote scats. Scats 1 inch (2.5

cm) or larger in diameter are probably from wolves;

smaller scats may be from wolves or coyotes. Wolf scats

frequently contain large amounts of hair and bone

fragments. An analysis of the hair contained in scats

may indicate possible livestock depredation. Since

wolves feed primarily on big game, their scats are not

as likely to contain the fine fur or the small bones and

teeth that are often found in coyote scats.

During hard winters, gray

wolves may contribute to the decline of populations of

deer, moose, and caribou in northern areas (Gauthier and

Theberge 1987). Studies in Minnesota (Mech and Karns

1977), Isle Royale (Peterson 1977), and Alaska (Gasaway

et al. 1983, Ballard and Larsen 1987) indicate that

predation by wolves, especially during severe winters,

may bring about marked declines in ungulate populations.

It appears that after ungulate populations reach low

levels, wolves may exert long-term control over their

prey populations and delay their increase.

Legal Status

All gray wolves in the

contiguous 48 states are classified as “endangered”

except for members of the Minnesota population, which

are classified as “threatened.” The maximum penalty for

illegally killing a wolf is imprisonment of not more

than 1 year, a fine of not more than $20,000, or both.

The classification of the wolf in Minnesota was changed

from “endangered” to “threatened” in April 1978. This

classification allows a variety of management options,

including the killing of wolves that are preying on

livestock by authorized federal or state personnel. In

Canada and Alaska, gray wolves are considered both

furbearers and game animals and are subject to sport

harvest and control measures regulated by province or

state agencies.

Red wolves are classified

as “endangered” in the United States. This

classification restricts control of red wolves to

authorized federal or state damage control personnel,

who may capture and relocate red wolves that are preying

on livestock.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Fences may help prevent

livestock losses to wolves. Exclude wolves with

well-maintained woven-wire fences that are 6 to 7 feet

(1.8 to 2.1 m) high. Install electrically charged wires

along the bottom and top of woven-wire fences to

increase their effectiveness. Several antipredator

fencing designs are available (Thompson 1979, Dorrance

and Bourne 1980, Linhart et al. 1984).

Cultural Methods

Livestock carcasses left

in or near pastures may attract wolves and other

predators to the area and increase the chances of

depredation. Remove and properly dispose of all dead

livestock by rendering, burying, or burning.

Calves and lambs are

particularly vulnerable to predators, and cows are

vulnerable while giving birth. Confine cows and ewes to

barnyard areas during calving and lambing season if

possible or maintain them near farm buildings. Hold

young livestock near farm buildings for 2 weeks or

longer, before moving them with the herd to pastures or

rangeland. As newborns mature they are better able to

stay with their mothers and the herd or flock, and are

less likely to be killed by wolves.

Nighttime losses of sheep

to wolves can be reduced by herding the sheep close to

farm buildings at night or putting them in pens where

possible.

If wolf depredation is

suspected, livestock producers should observe their

livestock as often as possible. Frequent observation may

be difficult in large wooded pastures or on large tracts

of open rangeland. The more often livestock are checked,

however, the more likely that predation will be

discovered. Frequent checks will also help the operator

determine if any natural mortality is occurring in the

herd or flock, and if any livestock thought to be

pregnant are barren and not producing. The presence of

humans near herds and flocks also tends to decrease

damage problems.

Frightening

Livestock guarding dogs

have been used for centuries in Europe and Asia to

protect sheep and other types of livestock. The dogs are

bonded socially to a particular type of livestock. They

stay with the livestock without harming them and either

passively repel predators by their presence or chase

predators away. Livestock guarding dogs are currently

being used by producers in the western United States to

protect sheep and other livestock from coyotes and

bears. They have been used in Minnesota to protect sheep

from coyotes and cattle from wolves. The most common

breeds of dogs used in the United States are the

Anatolian shepherd, Great Pyrennees, Komondor, Akbash

dogs, Kuvasz, Maremma, and Shar Plainintez. Livestock

guarding dogs should be viewed as a supplement to other

forms of predator control. They usually do not provide

an immediate solution to a predator problem because time

must be spent raising puppies or bonding the dogs to the

livestock they protect. Green et al. (1984) and Green

and Woodruff (1990) discuss proper methods for selecting

and training livestock guarding dogs and reasonable

expectations for effectiveness of guarding dogs against

predators. Consult with USDA-APHIS-ADC personnel for

additional information.

Strobe light/siren devices

(Electronic Guard [USDA-APHIS-ADC]) may be used to

reduce livestock depredation up to 4 months. Such

devices are probably most effective in small, open

pastures, around penned livestock, or in situations

where other lethal methods may not be acceptable. They

can also provide short-term protection from wolves while

other control methods are initiated.

Toxicants

None are registered for

wolves in the United States.

Fumigants

None are registered for

wolves in the United States.

Trapping

Control of damage caused

by wolves is best accomplished through selective

trapping of depredating wolves. Another method is to

classify wolves as furbearers and/or game animals and

encourage sport harvest to hold wolf populations at

acceptable levels. The Alberta Fish and Wildlife

Division has used this approach successfully in Canada,

where gray wolves are classified as furbearers. A

similar approach was proposed by the Minnesota

Department of Natural Resources in 1980 and 1982 to help

control the expanding wolf population in Minnesota, but

it was ruled illegal because of the wolf’s “threatened”

status in Minnesota.

Steel leghold traps, Nos.

4, 14, 114, and 4 1/2 Newhouse or Nos. 4 and 7 McBride

are recommended for capturing wolves. Nos. 4 and 14

Newhouse traps and the No. 4 McBride trap are routinely

used for research and depre-dation-control trapping of

wolves in Minnesota. Some wolf trappers feel that Nos. 4

and 14 Newhouse traps are too small for wolves. Where

larger subspecies of the gray wolf exist, use the No. 4

1/2 Newhouse, No. 7 McBride, or the Braun wolf trap.

Set traps at natural scent

posts where wolves urinate and/or defecate along their

travel routes. Make artificial scent posts by placing a

small quantity of wolf urine, lure, or bait on weeds,

clumps of grass, low bushes, log ends, or bones located

along wolf travel routes. Place traps near the carcasses

of animals killed or scavenged by wolves, at trail

junctions, or at water holes on open range. Set snares

(Thompson 4xx or 5xx, Gregerson No. 14) at holes in or

under fences where wolves enter livestock confinement

areas, or where wolves create trails in heavy cover.

Use traps and snares that

are clean and free of foreign odor. Remove grease and

oil from new traps and snares, set them outside until

slightly rusted, and then boil them in a solution of

water and logwood trap dye. Wear gloves when handling

traps and snares to minimize human odor. While

constructing the set, squat or kneel on a clean canvas

“setting cloth” to minimize human odor and disturbance

at the site. Traps may be either staked or attached to a

draghook. A trap that is staked should have about 4 feet

(1.2 m) of chain attached to it. A trap with a draghook

should have 6 to 8 feet (1.8 to 2.4 m) of chain

attached.

Shooting

Where legal, local wolf

populations can be reduced by shooting. Call wolves into

rifle range using a predator call or by voice howling.

Aerial hunting by

helicopter or fixed-wing aircraft is one of the most

efficient canid control techniques available where it is

legal and acceptable to the general public. Aerial

hunting can be economically feasible when losses are

high and the wolves responsible for depredation can be

taken quickly. When a pack of wolves is causing damage,

it may be worthwhile to trap one or two members of the

pack, outfit them with collars containing radio

transmitters and release them. Wolves are highly social

and by periodically locating the radiotagged wolves with

a radio receiver, other members of the pack may be found

and shot. The wolves wearing radio collars can then be

located and shot. This technique has been used

effectively by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Other Methods

In situations where lethal

control of depredating wolves may not be authorized (USFWS

1987), aerial hunting by helicopter can be used to dart

and chemically immobilize depredating wolves so that

they can be relocated from problem areas. Some recent

wolf control actions in Montana have used this

technique.

Long-range land-use

planning should solve most conflicts between livestock

producers and wolves. When wolves are present in the

vicinity of livestock, predation problems are likely to

develop. Therefore, care should be taken in selecting

areas for reestablishing wolf populations to assure that

livestock production will not be threatened by wolves.

Economics of Damage and

Control Wolves can sometimes cause serious economic

losses to individual livestock producers. Minnesota,

Wisconsin, and Montana have established compensation

programs to pay producers for damage caused by wolves.

In recent years, $40,000 to $45,000 has been paid

annually to Minnesota producers for verified claims of

wolf damage. Control of depredating wolves is often

economically feasible, but it can be time-consuming and

labor intensive. If wolves can be trapped, snared, or

shot at depredation sites, the cost is usually low.

Deer, moose, and other

ungulates have great economic and aesthetic value, but

wolves have strong public support. Thus, wolf control is

often highly controversial. Where wolves are the

dominant predator on an ungulate species and prey

numbers are below carrying capacity, a significant

reduction in wolf numbers can produce increases in the

number of ungulate prey (Gasaway et al 1983, Gauthier

and Theberge 1987) and therefore sometimes can be

economically justified. When control programs are

terminated, wolves may rapidly recover through

immigration and reproduction (Ballard et al. 1987).

Therefore, wolf control must be considered as an

acceptable management option (Mech 1985).

Acknowledgments

Information contained in

the sections on identification, habitat, food habits,

and general biology are adapted from Mech (1970). The

manual,

Methods of Investigating

Predation of Domestic Livestock, by Roy and Dorrance was

very helpful in developing the section on wolf damage

identification. Recommendations for preventing or

reducing wolf damage were developed in association with

Dr. Steven H. Fritts. We would also like to thank Scott

Hygnstrom for reviewing this chapter and providing many

helpful comments.

Figure 1 from Schwartz and

Schwartz (1981).

Figure 2 adapted from

Schwartz and Schwartz (1981) by Jill Sack Johnson.

Figure 3 adapted from a

Michigan Department of Natural Resources pamphlet.

For Additional Information

Abraham, G. R., D. W. Peterson, J. Herring, M. A. Young,

and C. J. Carley. 1980. Red wolf recovery plan. US Fish

Wildl. Serv., Washington, DC. 22 pp.

Ballard, W. B., and D. G.

Larsen. 1987. Implications of predator-relationships to

moose management. Swedish Wildl. Res. Suppl. 1:581-602.

Ballard, W. B., J. S.

Whitman, and C. L. Gardner. 1987. Ecology of an

exploited wolf population in south-central Alaska. Wildl.

Mono. 98. 54 pp.

Carbyn, L. N., ed. 1983.

Wolves in Canada and Alaska: their status, biology, and

management. Can. Wildl. Serv. Rep. 45, Ottawa. 135 pp.

Dorrance, M. J., and J.

Bourne. 1980. An evaluation of anti-coyote electric

fencing. J. Range Manage. 33:385-387.

Fritts, S. H., W. J. Paul,

L. D. Mech, and D. P. Scott. 1992. Trends and management

of wolf-livestock conflicts in Minnesota. US Fish Wildl.

Serv. Resour. Publ. 181., Washington, DC. 27 pp.

Gasaway, W. C., R. O.

Stephenson, J. L. David, P. K. Shepherd, and O. E.

Burris. 1983. Interrelationships of wolves, prey, and

man in interior Alaska. Wildl. Mono. 84. 50 pp.

Gauthier, D. A., and J. B.

Theberge. 1987. Wolf predation. Pages 120-127 in M.

Novak, J. A. Baker, M. E. Obbard, and B. Mallach, eds.

Wild furbearer management and conservation in North

America. Ont. Minist. Nat. Resour., Toronto.

Green, J. S., and R. A.

Woodruff. 1990. Livestock guarding dogs: protecting

sheep from predators. US Dep. Agric. Info. Bull. 588. 31

pp.

Green, J. S., R. A.

Woodruff, and T. T. Tueller. 1984. Livestock guarding

dogs for predator control: costs, benefits, and

practicality. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 12:44-50.

Linhart, S. B., J. D.

Roberts, and G. J. Dasch. 1982. Electric fencing reduces

coyote predation on pastured sheep. J. Range Manage.

35:276-281.

Linhart, S. B., R. T.

Sterner, G. J. Dasch, and J. W. Theade. 1984. Efficacy

of light and sound stimuli for reducing coyote predation

upon pastured sheep. Prot. Ecol. 6:75-84.

Mech, L. D. 1970. The

wolf: the ecology and behavior of an endangered species.

The Natural History Press, Doubleday, New York. 384 pp.

Mech, L. D. 1985. How

delicate is the balance of nature? Natl. Wildl.,

February-March:54-58.

Mech, L. D., and P. D.

Karns. 1977. Role of the wolf in a deer decline in the

Superior National Forest. US Dep. Agric. For. Serv. Res.

Rep. NC-148. 23 pp.

Murie, O. J. 1954. A field

guide to animal tracks. The Riverside Press, Cambridge,

Massachusetts. 374 pp.

Paradiso, J. L., and R. M.

Nowak. 1972. A report on the taxonomic status and

distribution of the red wolf. US Dep. Inter. Special Sci.

Rep. Wildl. 145. 36 pp.

Peterson, R. O. 1977. Wolf

ecology and prey relationships on Isle Royale. US Natl.

Park Serv. Sci. Mono. 11. 210 pp.

Phillips, M. K., and W. T.

Parker. 1988. Red wolf recovery: a progress report.

Conserv. Biol. 2:139-141.

Roy, L. D., and M. J.

Dorrance. 1976. Methods of investigating predation of

domestic livestock. Alberta Agric. Plant Ind. Lab.,

Edmonton. 54 pp.

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri, rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp.

Shaw, J. H. 1975. Ecology,

behavior, and systematics of the red wolf (Canis rufus).

Ph.D. Diss. Yale Univ. 99 pp.

Thompson, B. C. 1979.

Evaluation of wire fences for coyote control. J. Range

Manage. 32:457-461.

US Fish and Wildlife

Service. 1987. Northern Rocky Mountain wolf recovery

plan. US Fish Wildl. Serv., Denver, Colorado. 119 pp.

Young, S. P., and E. A.

Goldman. 1944. The wolves of North America. Parts 1 and

2. Dover Publ. Inc., New York. 636 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

01/23/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|