|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: Weasels |

|

|

Identification

Weasels

belong to the Mustelidae family, which also includes

mink, martens, fishers, wolverines, badgers, river

otters, black-footed ferrets, and four species of

skunks. Although members of the weasel family vary in

size and color (Fig. 1), they usually have long, slender

bodies, short legs, rounded ears, and anal scent glands.

A weasel’s hind legs are barely more than half as long

as its body (base of head to base of tail). The weasel’s

forelegs also are notably short. These short legs on a

long, slender body may account for the long-tailed

weasel’s (Mustela frenata) distinctive running gait.

At every bound the long body loops upward, reminding one

of an inchworm.

In

the typical bounding gait of the weasel, the hind feet

register almost, if not exactly, in the front foot

impressions, with the right front foot and hind feet

lagging slightly behind. The stride distance normally is

about 10 inches (25 cm).

Male

weasels are distinctly larger than females. The

long-tailed and short-tailed (M. erminea) weasels have a

black tip on their tails, while the least weasel (M.

nivalis) lacks the black tip

(Fig.

2). The long-tailed weasel some-its common name implies,

the least times is as long as 24 inches (61 cm). weasel

is the smallest, measuring only The short-tailed weasel

is considerably 7 or 8 inches (18 to 20 cm) long and

smaller, rarely longer than 13 inches weighing 1 to 2

1/2 ounces (28 to 70 g). (33 cm) and usually weighing

between Many people assume the least weasel 3 and 6

ounces (87 and 168 g). Just as is a baby weasel since it

is so small.

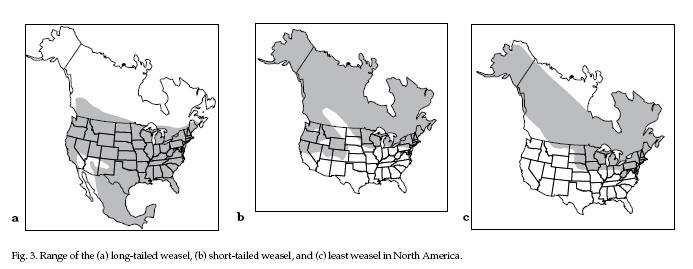

Range

Three species of weasels live in North America. The most

abundant and widespread is the long-tailed weasel. Some

that occur in parts of Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and New

Mexico have a dark “mask” and are often called

bridled weasels. The short-tailed weasel occurs in

Canada, Alaska, and the northeastern, Great Lakes, and

northwestern states, while the least weasel occurs in

Canada, Alaska, and the northeastern and Great Lakes

states (Fig. 3).

Habitat

Some authors report finding weasels only in places with

abundant water, although small rodents, suitable as

food, were more abundant in surrounding habitat. Weasels

are commonly found along roadsides and around farm

buildings. The absence of water to drink is thought to

be a limiting factor (Henderson and Stardom 1983).

A

typical den has two surface openings about 2 feet (61

cm) apart over a burrow that is 3 to 10 feet (0.9 to 3

m) long. Other weasel dens have been found in the trunk

of an old uprooted oak, in a bag of feathers, in a

threshing machine, in the trunk of a hollow tree, in an

old mole run, a gopher burrow, and a prairie dog burrow

(Henderson and Stardom 1983).

Food

Habits Food

Habits

The

weasel family belongs to the order Carnivora. With the

exception of the river otter, all members of the weasel

family feed primarily on insects and small rodents (Fig.

4). Their diet consists of whatever meat they can obtain

and may include birds and bird eggs.

As

predators, they play an important role in the ecosystem.

Predators tend to hunt the most abundant prey, turning

to another species if the numbers of the first prey

become scarce. In this way, they seldom endanger the

long-term welfare of the animal populations they prey

upon.

Long-tailed

weasels typically prey on one species that is

continually available. The size of the prey population

varies from year to year and from season to season. At

times, weasels will kill many more individuals of a prey

species than they can immediately eat. Ordinarily, they

store the surplus for future consumption, much the same

as squirrels gather and store nuts.

Pocket

gophers are the primary prey of long-tailed weasels. In

some regions these gophers are regarded as nuisances

because they eat alfalfa plants in irrigated meadows and

native plants in mountain meadows where livestock graze.

Because of its predation on pocket gophers and other

rodents, the long-tailed weasel is sometimes referred to

as the farmer’s best friend. This statement, however,

is an oversimplification of a biological relationship.

Weasels

prefer a constant supply of drinking water. The

long-tailed weasel drinks up to 0.85 fluid ounces (26

ml) daily.

General

Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Weasels are active

in both winter and summer; they do not hibernate.

Weasels are commonly thought to be nocturnal but

evidence indicates they are more diurnal in summer than

in winter.

Home

range sizes vary with habitat, population density,

season, sex, food availability, and species (Svendsen

1982). The least weasel has the smallest home range.

Males use 17 to 37 acres (7 to 15 ha), females 3 to 10

acres (1 to 4 ha). The short-tailed weasel is larger

than the least weasel and has a larger home range. Male

short-tailed weasels use an average of 84 acres (34 ha),

and females 18 acres (7 ha), according to snow tracking.

The

long-tailed weasel has a home range of 30 to 40 acres

(12 to 16 ha), and males have larger home ranges in

summer than do females. The weasels appear to prefer

hunting certain coverts with noticeable regularity but

rarely cruise the same area on two consecutive nights.

Weasel

population densities vary with season, food

availability, and species. In favorable habitat, maximum

densities of the least weasel may reach 65 per square

mile (169/km2); the short-tailed weasel, 21 per square

mile (54/km2); and the long-tailed weasel, 16 to 18 per

square mile (40 to 47/km2). Population densities

fluctuate considerably with year-to-year changes in

small mammal abundance, and densities differ greatly

among habitats.

Weasels,

like all mustelids, produce a pungent odor. When

irritated, they discharge the odor, which can be

detected at some distance (Jackson 1961).

Long-tailed

weasels mate in late summer, mostly from July through

August. Females are induced ovulators and will remain in

heat for several weeks if they are not bred. There is a

long delay in the implantation of the blastocyst in the

uterus, and the young are born the following spring,

after a gestation period averaging 280 days. Average

litters consist of 6 young, but litters may include up

to 9 young. The young are blind at birth and their eyes

open in about 5 weeks. They mature rapidly and at 3

months of age the females are fully grown. Young females

may become sexually mature in the summer of their birth

year.

Damage

and Damage Identification

Occasionally weasels raid

poultry houses at night and kill or injure domestic

fowl. They feed on the warm blood of victims bitten in

the head or neck. Rat predation on poultry usually

differs in that portions of the body may be eaten and

carcasses dragged into holes or concealed locations.

Legal

Status

All three weasels generally are considered

furbearers under state laws, and a season is normally

established for fur harvest. Check local and state laws

before undertaking weasel control measures.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Weasels

can be excluded from poultry houses and other structures

by closing all openings larger than 1 inch (2.5 cm). To

block openings, use 1/2-inch (1.3-cm) hardware cloth,

similar wire mesh, or other materials.

Trapping

Weasels

are curious by nature and are rather easily trapped in

No. 0 or 1 steel leghold traps. Professional trappers in

populated areas use an inverted wooden box 1 or 2 feet

(30 or 60 cm) long, such as an apple box, with a 2-to

3-inch (5-to 8cm) round opening cut out in the lower

part of both ends (Fig. 5). Dribble a trail of oats or

other grain through the box. Mice will frequent it to

eat the grain and weasels will investigate the scent of

the mice. A trap should be set inside the box, directly

under the hole at each end of the box. Keep the trap pan

tight to prevent the mice from setting off the trap.

Alternatively,

make a hole in only one end of the box and suspend a

fresh meat bait against the opposite end of the box. Set

the trap directly under the bait.

Trap

sets in old brush piles, under outbuildings, under

fences, and along stone walls are also suggested, since

the weasel is likely to investigate any small covered

area. Trap sets should be protected by objects such as

boards or tree limbs to protect nontarget wildlife.

Weasels

can also be captured in live traps with fresh meat as

suitable bait. If trapping to alleviate damage is to be

conducted at times other than the designated season, the

local wildlife agency representative must be notified.

Economics

of Damage and Control

Svendsen (1982) writes:

“Overall,

weasels are more of an asset than a liability. They eat

quantities of rats and mice that otherwise would eat and

damage additional crops and produce. This asset is

partially counter-balanced by the fact that weasels

occasionally kill beneficial animals and game species.

The killing of domestic poultry may come only after the

rat population around the farmyard is diminished. In

fact, rats may have destroyed more poultry than the

weasel. In most cases, a farmer lives with weasels on

the farm for years without realizing that they are even

there, until they kill a chicken.”

Acknowledgments

Figures 1, 2, and 4 adapted by Jill Sack Johnson from

“Weasel Family of Alberta” (no date), Alberta Fish

and Wildlife Division, Alberta Energy and Natural

Resources, Edmonton (with permission).

Figure

3 adapted from Burt and Grossenheider (1976) by Jill

Sack Johnson.

Figure

5 adapted from a publication by the US Fish and Wildlife

Service.

For

Additional Information

Burt, W. H., and R. P. Grossenheider. 1976. A field guide to the mammals, 3d

ed. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. 289 pp.

Fitzgerald,

B. M. 1977. Weasel predation on a cyclic population of

the montane vole (Microtus montanus) in California. J.

An. Ecol. 46:367-397.

Glover,

F. A. 1942. A population study of weasels in

Pennsylvania. M.S. Thesis, Pennsylvania State Univ.

University Park. 210 pp.

Hall,

E. R. 1951. American weasels. Univ. Kansas Museum Nat.

Hist. Misc. PubL. 4:1-466.

Hall,

E. R. 1974. The graceful and rapacious weasel. Nat. Hist.

83(9):44-50.

Hamilton,

W. J., Jr. 1933. The weasels of New York. Am. Midl. Nat.

14:289-337.

Henderson,

F. R., and R. R. P. Stardom.1983. Short-tailed and

long-tailed weasel. Pages 134-144 in E. F. Deems, Jr.

and D. Purseley, eds. North American furbearers: a

contemporary reference. Internatl. Assoc. Fish Wildl.

Agencies Maryland Dep. Nat. Resour.

Jackson,

H. H. T. 1961. Mammals of Wisconsin. Univ. Wisconsin

Press, Madison. 504 pp.

King,

C. M. 1975. The home range of the weasel (Mustela

nivalis) in an English woodland. J. An. Ecol.

44:639-668.

MacLean,

S. F., Jr., B. M. Fitzgerald, and F. A. Pitelka. 1974.

Population cycles in arctic lemmings: winter

reproduction and predation by weasels. Arctic Alpine

Res. 6:1-12.

Polderboer,

E. B., L. W. Kuhn, and G. O. Hendrickson. 1941. Winter

and spring habits of weasels in central Iowa. J. Wildl.

Manage. 5:115-119.

Quick,

H. F. 1944. Habits and economics of New York weasel in

Michigan. J. Wildl. Manage. 8:71-78.

Quick,

H. F. 1951. Notes on the ecology of weasels in Gunnison

County, Colorado. J. Mammal. 32:28-290.

Schwartz,

C. W. and E. R. Schwartz. 1981. The Wild mammals of

Missouri, rev. ed. Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356

pp.

Svendsen,

G. E. 1982. Weasels. Pages 613-628 in J. A. Chapman and

G. A. Feldhamer, eds., Wild mammals of North America:

biology, management, and economics. The Johns Hopkins

Univ. Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Editors

Scott

E. Hygnstrom Robert M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION

AND CONTROL OF WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative

Extension Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural

Resources University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United

States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health

Inspection Service Animal Damage Control

Great

Plains Agricultural Council Wildlife Committee

01/23/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|