|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: Skunks |

|

|

Identification

The skunk, a member of the

weasel family, is represented by four species in North

America. The skunk has short, stocky legs and

proportionately large feet equipped with well-developed

claws that enable it to be very adept at digging.

The striped skunk (Fig. 1)

is characterized by prominent, lateral white stripes

that run down its back. Its fur is otherwise jet black.

Striped skunks are the most abundant of the four

species. The body of the striped skunk is about the size

of an ordinary house cat (up to 29 inches [74 cm] long

and weighing about 8 pounds [3.6 kg] ). The spotted

skunk (Fig. 1) is smaller (up to 21 inches [54 cm] long

and weighing about 2.2 pounds [1 kg]), more weasel-like,

and is readily distinguishable by white spots and short,

broken white stripes in a dense jet-black coat.

The hooded skunk (Mephitis

macroura) is identified by hair on the neck that is

spread out into a ruff. It is 28 inches (71 cm) long and

weighs the same as the striped skunk. It has an

extremely long tail, as long as the head and body

combined. The back and tail may be all white, or nearly

all black, with two white side stripes. The hog-nosed

skunk (Conepatus leucontus) has a long snout that is

hairless for about 1 inch (2.5 cm) at the top. It is 26

inches (66 cm) long and weighs 4 pounds (1.8 kg). Its

entire back and tail are white and the lower sides and

belly are black. Skunks have the ability to discharge

nauseating musk from the anal glands and are capable of

several discharges, not just one.

Range

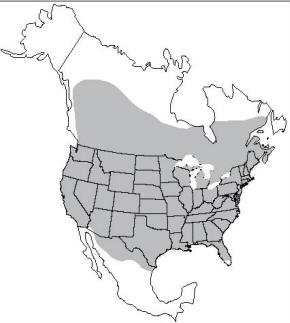

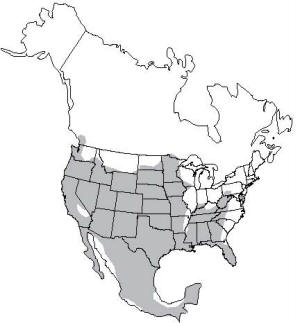

The

striped skunk is common throughout the United States and

Canada (Fig. 2a). Spotted skunks are uncommon in some

areas, but distributed throughout most of the United

States and northern Mexico (Fig 2b) The hooded skunk and

the hog-nosed skunk are much less common than striped

and spotted skunks. Hooded skunks are limited to

southwestern New Mexico and western Texas. The hog-nosed

skunk is found in southern Colorado, central and

southern New Mexico, the southern half of Texas, and

northern Mexico. The

striped skunk is common throughout the United States and

Canada (Fig. 2a). Spotted skunks are uncommon in some

areas, but distributed throughout most of the United

States and northern Mexico (Fig 2b) The hooded skunk and

the hog-nosed skunk are much less common than striped

and spotted skunks. Hooded skunks are limited to

southwestern New Mexico and western Texas. The hog-nosed

skunk is found in southern Colorado, central and

southern New Mexico, the southern half of Texas, and

northern Mexico.

Fig. 2a. Range of the

striped skunk in North America. Fig. 2b. Range of the

spotted skunk in North America.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Adult skunks begin

breeding in late February. Yearling females (born in the

preceding year) mate in late March. Gestation usually

lasts 7 to 10 weeks. Older females bear young during the

first part of May, while yearling females bear young in

early June. There is usually only 1 litter annually.

Litters commonly consist of 4 to 6 young, but may have

from 2 to 16. Younger or smaller females have smaller

litters than older or larger females. The young stay

with the female until fall. Both sexes mature by the

following spring. The age potential for a skunk is about

10 years, but few live beyond 3 years in the wild.

The

normal home range of the skunk is l/2 to 2 miles (2 to 5

km) in diameter. During the breeding season, a male may

travel 4 to 5 miles (6.4 to 8 km) each night. The

normal home range of the skunk is l/2 to 2 miles (2 to 5

km) in diameter. During the breeding season, a male may

travel 4 to 5 miles (6.4 to 8 km) each night.

Skunks are dormant for

about a month during the coldest part of winter. They

may den together in winter for warmth, but generally are

not sociable. They are nocturnal in habit, rather

slow-moving and deliberate, and have great confidence in

defending themselves against other animals.

Habitat

Skunks inhabit clearings,

pastures, and open lands bordering forests. On prairies,

skunks seek cover in the thickets and timber fringes

along streams. They establish dens in hollow logs or may

climb trees and use hollow limbs.

Food Habits

Skunks eat plant and

animal foods in about equal amounts during fall and

winter. They eat considerably more animal matter during

spring and summer when insects, their preferred food,

are more available. Grasshoppers, beetles, and crickets

are the adult insects most often taken. Field and house

mice are regular and important items in the skunk diet,

particularly in winter. Rats, cottontail rabbits, and

other small mammals are taken when other food is scarce.

Damage and Damage Identification

Skunks become a nuisance

when their burrowing and feeding habits conflict with

humans. They may burrow under porches or buildings by

entering foundation openings. Garbage or refuse left

outdoors may be disturbed by skunks. Skunks may damage

beehives by attempting to feed on bees. Occasionally,

they feed on corn, eating only the lower ears. If the

cornstalk is knocked over, however, raccoons are more

likely the cause of damage. Damage to the upper ears of

corn is indicative of birds, deer, or squirrels. Skunks

dig holes in lawns, golf courses, and gardens to search

for insect grubs found in the soil. Digging normally

appears as small, 3- to 4-inch (7- to 10-cm) cone-shaped

holes or patches of upturned earth. Several other

animals, including domestic dogs, also dig in lawns.

Skunks

occasionally kill poultry and eat eggs. They normally do

not climb fences to get to poultry. By contrast, rats,

weasels, mink, and raccoons regularly climb fences. If

skunks gain access, they will normally feed on the eggs

and occasionally kill one or two fowl. Eggs usually are

opened on one end with the edges crushed inward.

Weasels, mink, dogs and raccoons usually kill several

chickens or ducks at a time. Dogs will often severely

mutilate poultry. Tracks may be used to identify the

animal causing damage. Both the hind and forefeet of

skunks have five toes. In some cases, the fifth toe may

not be obvious. Claw marks are usually visible, but the

heels of the forefeet normally are not. The hindfeet

tracks are approximately 2 1/2 inches long (6.3 cm)

(Fig. 3). Skunk droppings can often be identified by the

undigested insect parts they contain. Droppings are 1/4

to 1/2 inch (6 to 13 mm) in diameter and 1 to 2 inches

(2.5 to 5 cm) long. Skunks

occasionally kill poultry and eat eggs. They normally do

not climb fences to get to poultry. By contrast, rats,

weasels, mink, and raccoons regularly climb fences. If

skunks gain access, they will normally feed on the eggs

and occasionally kill one or two fowl. Eggs usually are

opened on one end with the edges crushed inward.

Weasels, mink, dogs and raccoons usually kill several

chickens or ducks at a time. Dogs will often severely

mutilate poultry. Tracks may be used to identify the

animal causing damage. Both the hind and forefeet of

skunks have five toes. In some cases, the fifth toe may

not be obvious. Claw marks are usually visible, but the

heels of the forefeet normally are not. The hindfeet

tracks are approximately 2 1/2 inches long (6.3 cm)

(Fig. 3). Skunk droppings can often be identified by the

undigested insect parts they contain. Droppings are 1/4

to 1/2 inch (6 to 13 mm) in diameter and 1 to 2 inches

(2.5 to 5 cm) long.

Odor is not always a

reliable indicator of the presence or absence of skunks.

Sometimes dogs, cats, or other animals that have been

sprayed by skunks move under houses and make owners

mistakenly think skunks are present.

Rabies may be carried by

skunks on occasion. Skunks are the primary carriers of

rabies in the Midwest. When rabies outbreaks occur, the

ease with which rabid animals can be contacted

increases. Therefore, rabid skunks are prime vectors for

the spread of the virus. Avoid overly aggressive skunks

that approach without hesitation. Any skunk showing

abnormal behavior, such as daytime activity, may be

rabid and should be treated with caution. Report

suspicious behavior to local animal control authorities.

Legal Status

Striped skunks are not

protected by law in most states, but the spotted skunk

is fully protected in some. Legal status and licensing

requirements vary. Check with state wildlife officials

before removing any skunks.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Keep skunks from denning

under buildings by sealing off all foundation openings.

Cover all openings with wire mesh, sheet metal, or

concrete. Bury fencing 1 1/2 to 2 feet (0.4 to 0.6 m)

where skunks can gain access by digging. Seal all

ground-level openings into poultry buildings and close

doors at night. Poultry yards and coops without

subsurface foundations may be fenced with 3-foot (1-m)

wire mesh fencing. Bury the lowest foot (0.3 m) of

fencing with the bottom 6 inches (15.2 cm) bent outward

from the yard or building. Skunks can be excluded from

window wells or similar pits with mesh fencing. Place

beehives on stands 3 feet (1 m) high. It may be

necessary to install aluminum guards around the bases of

hives if skunks attempt to climb the supports. Skunks,

however, normally do not climb. Use tight-fit-ting lids

to keep skunks out of garbage cans.

Habitat Modification

Properly dispose of

garbage or other food sources that will attract skunks.

Skunks are often attracted to rodents living in barns,

crawl spaces, sheds, and garages. Rodent control

programs may be necessary to eliminate this attraction.

Debris such as lumber,

fence posts, and junk cars provide shelter for skunks,

and may encourage them to use an area. Clean up the area

to discourage skunks.

Frightening

Lights and sounds may

provide temporary relief from skunk activity.

Repellents

There are no registered

repellents for skunks. Most mammals, including skunks,

can sometimes be discouraged from entering enclosed

areas with moth balls or moth flakes (naphthalene). This

material needs to be used in sufficient quantities and

replaced often if it is to be effective. Ammonia-soaked

cloths may also repel skunks. Repellents are only a

temporary measure. Permanent solutions require other

methods.

Toxicants

No toxicants are

registered for use in controlling skunks.

Fumigants

Two types of gas

cartridges are registered for fumigating skunk burrows.

Fumigation kills skunks and any other animals present in

the burrows by suffocation or toxic gases. Follow label

directions and take care to avoid fire hazards when used

near structures.

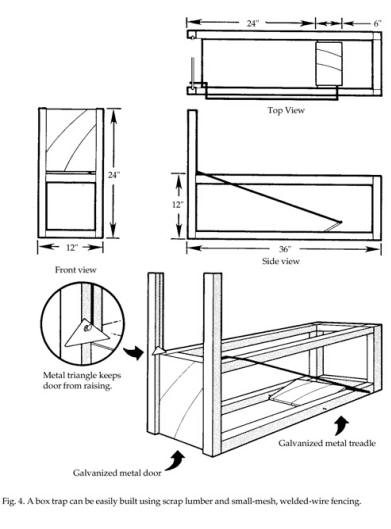

Trapping Trapping

Box Traps. Skunks can be

caught in live traps set near the entrance to their den.

When a den is used by more than one animal, set several

traps to reduce capture time. Live traps can be

purchased or built. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate traps

that can be built easily. Consult state wildlife agency

personnel before trapping skunks.

Use canned fish-flavored

cat food to lure skunks into traps. Other food baits

such as peanut butter, sardines, and chicken entrails

are also effective. Before setting live traps, cover

them with canvas to reduce the chances of a trapped

skunk discharging its scent. The canvas creates a dark,

secure environment for the animal. Always approach a

trap slowly and quietly to prevent upsetting a trapped

skunk. Gently remove the trap from the area and release

or kill the trapped skunk.

Captured skunks should be

transported at least 10 miles (16 km) and released in a

habitat far from human dwellings. Attach a length of

heavy string or fishing line to the trap cover and

release the skunk from a distance. Removing and

transporting a livetrapped skunk may appear to be a

precarious business, but if the trap is completely

covered, it is a proven, effective method for relocating

a skunk. If the skunk is to be killed, the US Department

of Agriculture recommends shooting or euthanization with

CO.

Leghold Traps.

Leghold traps should not be used to catch skunks near

houses because of potential problem of scent discharge.

To remove a live skunk caught in a leghold trap, a

veterinarian or wildlife official may first inject it

with a tranquilizer, then remove it from the trap for

disposal or release elsewhere.

Shooting

Skunks caught in leghold

traps may be shot. Shooting the skunk in the middle of

the back to sever the spinal cord and paralyze the hind

quarters may prevent the discharge of scent. Shooting in

the back should be followed immediately by shooting in

the head. Most people who shoot trapped skunks should

expect a scent discharge.

Other Methods

Skunk Removal. The

following steps are suggested for removing skunks

already established under buildings.

-

Seal all possible

entrances along the foundation, but leave the main

burrow open.

-

Sprinkle a layer of

flour 2 feet (0.6 m) in circumference on the ground

in front of the opening.

-

After dark, examine

the flour for tracks which indicate that the skunk

has left to feed. If tracks are not present,

reexamine in an hour.

-

After the den is

empty, cover the remaining entrance immediately.

-

Reopen the entrance

the next day for 1 hour after dark to allow any

remaining skunks to exit before permanently sealing

the entrance.

A wooden door suspended

from wire can be improvised to allow skunks to leave a

burrow but not to reenter. Burrows sealed from early May

to mid-August may leave young skunks trapped in the den.

If these young are mobile they can usually be

box-trapped easily using the methods previously

described. Where skunks have entered a garage, cellar,

or house, open the doors to allow the skunks to exit on

their own. Do not prod or disturb them. Skunks trapped

in cellar window wells or similar pits may be removed by

nailing cleats at 6-inch (15-cm) intervals to a board.

Lower the board into the well and allow the skunk to

climb out on its own. Skunks are mild-tempered animals

that will not defend themselves unless they are cornered

or harmed. They usually provide a warning before

discharging their scent, stamping their forefeet rapidly

and arching their tails over their backs. Anyone

experiencing such a threat should retreat quietly and

slowly. Loud noises and quick, aggressive actions should

be avoided.

Odor Removal. Many

individuals find the smell of skunk musk nauseating. The

scent is persistent and difficult to remove. Diluted

solutions of vinegar or tomato juice may be used to

eliminate most of the odor from people, pets, or

clothing. Clothing may also be soaked in weak solutions

of household chloride bleach or ammonia. On camping

trips, clothing can be smoked over a cedar or juniper

fire. Neutroleum alpha is a scent-masking solution that

can be applied to the sprayed area to reduce the odor.

It is available through some commercial cleaning

suppliers and the local USDA-APHIS-ADC office. Walls or

structural areas that have been sprayed by skunks can be

washed down with vinegar or tomato juice solutions or

sprayed with neutroleum alpha. Use ventilation fans to

speed up the process of odor dissipation. Where musk has

entered the eyes, severe burning and an excessive tear

flow may occur. Temporary blindness of 10 or 15 minutes

may result. Rinse the eyes with water to speed recovery.

[For more on deodorizing click deodorizing]

Economics of Damage and Control

Skunks should not be

needlessly destroyed. They are highly beneficial to

farmers, gardeners, and landowners because they feed on

large numbers of agricultural and garden pests. They

prey on field mice and rats, both of which may girdle

trees or cause health problems. Occasionally they eat

moles, which cause damage to lawns, or insects such as

white grubs, cutworms, potato beetle grubs, and other

species that damage lawns, crops, or hay.

Skunks occasionally feed

on ground-nesting birds, but their impact is usually

minimal due to the large abundance of alternative foods.

Skunks also feed on the eggs of upland game birds and

waterfowl. In waterfowl production areas, nest

destruction by egg-seeking predators such as skunks can

significantly reduce reproduction. The occasional

problems caused by the presence of skunks are generally

outweighed by their beneficial habits. Some people even

allow skunks to den under abandoned buildings or

woodpiles. Unless skunks become really bothersome, they

should be left alone. An economic evaluation of the

feeding habits of skunks shows that only 5% of the diet

is made up of items that are economically valuable to

people.

The hide of the skunk is

tough, durable, and able to withstand rough use.

Generally there is little market for skunk pelts but

when other furbearer prices are high, skunks are worth

pelting.

Acknowledgments

Much of the information

for this chapter was based on a publication by F. Robert

Henderson.

Figures 1 and 2 from

Schwartz and Schwartz (1981).

Figures 3 through 5 by

Jerry Downs, Graphic Artist, Cooperative Extension

Service, New Mexico State University.

For Additional Information

Burt, W. H., and R. P. Grossenheider. 1976. A field

guide to the mammals, 3d ed. Houghton Mifflin Co.,

Boston. 289 pp.

Deems, E. F., Jr., and D.

Pursley, eds. 1983. North American furbearers: a

contemporary reference. Int. Assoc. Fish Wildl. Agencies

and Maryland Dep. Nat. Resour. 223 pp.

Godin, A. J. 1982. Striped

and hooded skunks. Pages 674-687 in J. A. Chapman and G.

A. Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North America:

biology, management, and economics. The Johns Hopkins

Univ. Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Howard, W. E., and R. E.

Marsh. 1982. Spotted and hog-nosed skunks. Pages 664-673

in J. A. Chapman and G. A. Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals

of North America: biology, management, and economics.

The Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Rosatte, Richard C. 1987.

Striped, spotted, hooded, and hog-nosed skunk. Pages

598613 in M. Novak, J. A. Baker, M. E. Obbard, and B.

Malloch, eds. Wild furbearer management and conservation

in North America. Ministry of Nat. Resour., Ontario,

Canada.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

01/23/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|