|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: River Otters |

|

|

Fig. 1. The North American

river otter, Lutra canadensis

Identification

River

otters Lutra canadensis, Fig. 1) are best known for

their continuous and playful behavior, their aesthetic

value, and the value of their durable, high-quality fur.

They have long, streamlined bodies, short legs, and a

robust, tapered tail, all of which are well adapted to

their mostly aquatic habitat. They have prominent

whiskers just behind and below the nose, thick muscular

necks and shoulders, and feet that are webbed between

the toes. Their short but thick, soft fur is brown to

almost black except on the chin, throat, cheeks, chest,

and occasionally the belly, where it is usually lighter,

varying from brown to almost beige.

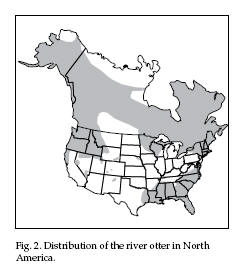

Fig.

2. Distribution of the river otter in North America. Fig.

2. Distribution of the river otter in North America.

Adult males usually

attain lengths of nearly 48 inches (122 cm) and weights

of about 25 pounds (11.3 kg), but may reach 54 inches

(137 cm) and 33 pounds (15 kg). Their sex can be readily

distinguished by the presence of a baculum (penile

bone). Females have 4 mammae on the upper chest and are

slightly smaller than males. Female adults measure about

44 inches (112 cm) and weigh 19 pounds (8.6 kg). The

mean weights and sizes of river otters in southern

latitudes tend to be lower than those in latitudes

farther north.

Range and Habitat

River

otters occur throughout North America except the arctic

slopes, the arid portions of the Southwest, and the

intensive agricultural and industrialized areas of the midwestern United States (Fig. 2). Their precolonial

range apparently included all of North America except

the arid Southwest and the northernmost portions of

Alaska and Canada. Otter populations are confined to

water courses, lakes, and wetlands, and therefore,

population densities are lower than those of terrestrial

species. Their extirpation from many areas is believed

to have been related more to poisoning by pesticides

bio-magnified in fishes, and to the indirect adverse

effects of water pollution on fish, their main food,

than to excessive harvest. The loss of ponds and other

wetland habitat that resulted from the extirpation of

beaver in the late 1800s may have adversely affected

continental populations of river otters more than any

other factor. Increases in the range and numbers of

river otters in response to the return of beaver has

been dramatic, particularly in the southeastern United

States. Recent releases totaling more than 1,000 otters

have been made in Arizona, Colorado, Iowa, Kansas,

Kentucky, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania,

Tennessee, and West Virginia in efforts to reestablish

local populations.

River otters are almost

invariably associated with water (fresh, brackish, and

salt water), although they may travel overland for

considerable distances. They inhabit lakes, rivers,

streams, bays, estuaries, and associated riparian

habitats. They occur at much higher densities in regions

of the Great Lakes, in brackish marshes and inlets, and

in other coastal habitats than farther inland. In colder

climates, otters frequent rapids and waterfall areas

that remain ice-free. Vegetative cover and altitude do

not appear to influence the river otter's

distribution as much as do good or adequate water

quality, the availability of forage fish, and suitable denning sites.

Food Habits

The diet of

the river otter throughout its range is primarily fish.

Numerous species and varieties of fresh and anadromous

fishes are eaten, but shellfish, crayfish, amphibians,

and reptiles are also frequently eaten, as are several

species of crabs in coastal marshes. Mammals and birds

are rarely eaten. Consumption of game fishes in

comparison to nongame (rough) fishes is generally in

proportion to the difficulty, or ease, with which they

can be caught. Because of the availability of abundant

alternate food species in warm water, losses of the warm

water sport fishes are believed minor compared to losses

river otters can inflict on cold water species such as

trout and salmon.

General Biology,

Reproduction, and Behavior The reproductive biology of

river otters and all other weasels is complex because of

a characteristic known as delayed implantation.

Following breeding and fertilization in spring, eggs (blastocysts)

exist in a free-floating state until the following

winter or early spring. Once they implant, fetal growth

lasts 60 to 65 days until the kits are born, usually in

spring (March through May) in most areas. In the

southern portion of the range the dates of birth occur

earlier, mostly in January and February, implying

implantation in November and December. Litters usually

contain 2 to 4 kits, and the female alone cares for the

young. They usually remain together as a family group

though the fall and into the winter months. Sexual

maturity in young is believed to occur at about 2 years

of age in females, but later in males.

River otters are

chiefly nocturnal, but they frequently are active during

daylight hours in undisturbed areas. Socially, the basic

group is the female and her offspring. They spend much

of their time feeding and at what appears to be group

play, repeatedly sliding down steep banks of mud or

snow. They habitually use specific sites (toilets) for

defecation. Their vocalizations include chirps, grunts,

and loud piercing screams. They are powerful swimmers

and are continuously active, alert, and quick—characteristics

that give them immense aesthetic and recreational value.

Their webbed feet, streamlined bodies, and long, tapered

tails enable them to move through water with agility,

grace, and speed. Seasonally, they may travel distances

of 50 to 60 miles (80 to 96 km) along streams or lake

shores, and their home ranges may be as large as 60

square miles (155 km2). Males have been recorded to

travel up to 10 miles (16 km) in 1 night.

River otters use a

variety of denning sites that seem to be selected based

on availability and convenience. Hollow logs, rock

crevices, nutria houses, and abandoned beaver lodges and

bank dens are used. They will also frequent unused or

abandoned human structures or shelters. Natal dens tend

to be located on small headwater branches or streams

leading to major drainages or lakes.

Damage and Damage

Identification

The presence of river otter(s) around or

in a fish hatchery, aquaculture, or fish culture

facility is a good indication that a damage problem is

imminent. Otter scats or toilets that contain scales,

exoskeletons, and other body parts of the species being

produced is additional evidence that damage is ongoing.

Uneaten parts of fish in shallow water and along the

shore is evidence that fish are being taken. Otters

usually eat all of a small catfish except for the head

and major spines, whereas small trout, salmon, and many

of the scaled fishes may be totally eaten. Uneaten

carcasses with large puncture holes are likely

attributable to herons. River otters can occasionally

cause substantial damage to concentrations of fishes in

marine aquaculture facilities. Often the damage involves

learned feeding behavior by one or a family of otters.

Legal Status

The river

otter is listed in Appendix II of the Convention on

International Trade in Endangered Species of Flora and

Fauna (CITES). Its inclusion in this appendix subjects

it to international restrictions and state/province

export quotas because of its resemblance to the European

Otter. Moreover, the river otter is totally protected in

17 states. Twenty-seven states have trapping seasons,

and four states and two provinces have hunting seasons.

Damage Prevention and

Control Methods

Because river otter damage has been

minor compared to that of other species, and because of

its legal status under the CITES Agreement, little

control research and experimentation has been done.

Registration of repellents, toxicants, or fumigants for

river otter control has not been sought. Alternate aquacultural practices and species, predator avoidance

behavior, and use of protective habitat have not been

fully explored. Careful assessment should be made of

reported damage to determine if nonlethal preventative

measures can be employed, and to ensure that if any

lethal corrective measures are employed, they do not

violate state or federal laws. Damage problems should

then be approached on an individual basis. Cultural

methods and habitat modification are normally not

applicable. Opportunities to use repellents, toxicants,

fumigants, and frightening devices are infrequent, yet

the development of any of these or other effective

nonlethal approaches would be preferable to lethal

control measures.

Exclusion

Fencing with

3 x 3-inch (7.6 x 7.6-cm) or smaller mesh wire can be an

economically effective method of preventing damage at aquacultural sites that are relatively small, or where

fish or aquaculture activities are concentrated. Fencing

is more economical for protection of small areas where

research, experimental, or propagation facilities such

as raceways, tanks, ponds, or other facilities hold

concentrations of fish. Hog wire-type fences have also

been used effectively, but these should be checked

occasionally to ensure that the lower meshes have not

been spread apart or raised to allow otters to enter.

Electric fences have

also been used, but they require frequent inspection and

maintenance, and like other fencing, are usually

impractical for protecting individual small ponds,

raceways, or tanks in a series. They are of greater

utility as a supplement to perimeter fences surrounding

an aquaculture facility.

Trapping

Traps that

have been used effectively for river otters include the Conibear® (sizes 220 and 330) or other similar

body-gripping traps and leghold traps (modified No. 1

1/2 soft-catch and No. 11 double longspring). The latter

two are usually employed to capture river otters for

restocking purposes. In water, body-gripping traps are

usually placed beneath the water surface or partially

submerged where runs become narrow or restricted (Fig.

3). They are effective when partially submerged at dam

crossings, the main runs in beaver ponds, or other

locations where otters frequently leave the water.

Body-gripping traps are also effective in otter trails

that connect pools of water or that cross small

peninsulas. In these sets, the trap should be placed at

a height to blend with the surrounding vegetation to

catch an otter that is running or sliding. After ice

forms on the surface of streams and lakes, some trappers

bait the triggers of body-gripping traps with whole

fish. River otter trapping is prohibited in 21 states

and one Canadian province. Check local regulations

before trapping.

Most

of the wild otters used for restocking in recent years

were caught with No. 11 longspring traps in coastal

Louisiana. These animals were usually caught in sets for

nutria, in traps that were set in narrow trails and

pullouts where shallow water necessitated that otters

walk rather than swim. Leghold traps are also effective

when placed in shallow edges of trails leading to otter

toilets or other areas they frequent. Leghold traps set

in out-of-water trails and peninsula crossings should be

covered with damp leaves or other suitable covering. Most

of the wild otters used for restocking in recent years

were caught with No. 11 longspring traps in coastal

Louisiana. These animals were usually caught in sets for

nutria, in traps that were set in narrow trails and

pullouts where shallow water necessitated that otters

walk rather than swim. Leghold traps are also effective

when placed in shallow edges of trails leading to otter

toilets or other areas they frequent. Leghold traps set

in out-of-water trails and peninsula crossings should be

covered with damp leaves or other suitable covering.

With the depression of

fur prices, nuisance beaver problems and efforts to

control them have increased substantially throughout the

United States. The killing of otters during beaver

control trapping can be minimized by using snares, but

they do occasionally sustain moderate injuries. In most

situations, snared river otters can be released

unharmed. Accordingly, snares are neither the most

effective, nor the most convenient devices for capturing

river otters or removing them from an area, and

therefore are not recommended for either.

Shooting

Shooting the

offending otters that cause damage problems will often

effectively prevent continued losses. Although otters

are shy, they are inquisitive and will often swim within

close range of a small rifle or shotgun. Extreme caution

should be taken to avoid ricochet when shooting a rifle

at objects surrounded by water.

Shooting river otters

for fur harvest is legal in four states and one Canadian

province. Check your local, state, and federal laws and

permits governing shooting, the use of lights after

dark, the seasons, and the possession of otter carcasses

or parts, to ensure that planned activities are legal.

Economics of Damage and

Control

Although individual incidences of river otter

damage and predation on fish can cause substantial

losses to pond owners and to fresh water and marine aquacultural interests, their total effects are believed

to be insignificant. Given the otter’s aesthetic

and recreational value, and its current legal status,

consideration of broad control programs are unwarranted

and undesirable.

Acknowledgments

Figure

1 from Schwartz and Schwartz (1981).

Figure 2 from Toweill

and Tabor (1982), adapted by Dave Thornhill, University

of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Figure 3 by Clint

Chapman, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

For Additional

Information

Hill, E. P. 1983. River otter Lutra

canadensis Pages 176-181 in E. F. Deems Jr. and D.

Pursley eds. North American furbearers, a contemporary

reference. Internat. Assoc. Fish Wildl. Agencies and

Maryland Dep. Nat. Resour.

Hill, E.P., and V.

Lauhachinda. 1980. Reproduction in river otters from

Alabama and Georgia. Pages 478-486 in J. A. Chapman and

D. Pursley eds., Proc. worldwide furbearer conf.

Maryland Dep. Nat. Resour., Annapolis.

Melquist, W. E., and

Ana E. Dronkert 1987. River otter. Pages 626-641 in M.

Novak, J. A. Baker, M. E. Obbard, and B. Malloch eds.

Wild furbearer management and conservation in North

America. Ontario Minister of Nat. Resour., Toronto.

Toweill, D. E., and J.

E. Tabor. 1982. River otter. Pages 688-703 in J. A.

Chapman and G. A. Feldhamer eds. Wild mammals of North

America: biology, management, and economics. The Johns

Hopkins Univ. Press., Baltimore, Maryland.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom

Robert M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL

OF WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States

Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health

Inspection Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains

Agricultural Council Wildlife Committee

01/23/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|