|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: Raccoons |

|

|

Fig. 1. The distinctively

marked raccoon (Procyon lotor) with water

Identification

The raccoon (Procyon lotor),

also called “coon,” is a stocky mammal about 2 to 3 feet

(61 to 91 cm) long, weighing 10 to 30 pounds (4.5 to

13.5 kg) (rarely 40 to 50 pounds [18 to 22.5 kg]). It is

distinctively marked, with a prominent black “mask” over

the eyes and a heavily furred, ringed tail (Fig. 1). The

animal is a grizzled salt-and-pepper gray and black

above, although some individuals are strongly washed

with yellow. Raccoons from the prairie areas of the

western Great Plains are paler in color than those from

eastern portions of the region.

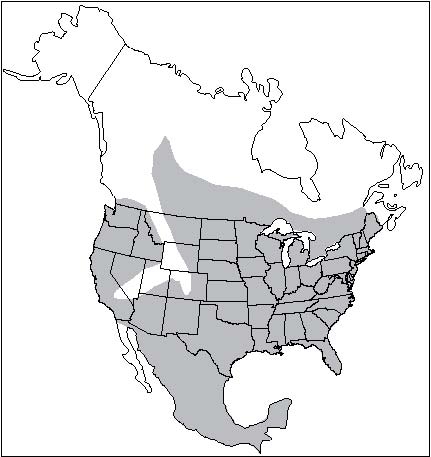

Fig. 2. Distribution of

the raccoon in North America.

Range Range

The raccoon is found

throughout the United States, with the exception of the

higher elevations of mountainous regions and some areas

of the arid Southwest (Fig. 2). Raccoons are more common

in the wooded eastern portions of the United States than

in the more arid western plains.

Habitat

Raccoons prefer hardwood

forest areas near water. Although commonly found in

association with water and trees, raccoons occur in many

areas of the western United States around farmsteads and

livestock watering areas, far from naturally occurring

bodies of permanent water. Raccoons den in hollow trees,

ground burrows, brush piles, muskrat houses, barns and

abandoned buildings, dense clumps of cattail, haystacks,

or rock crevices.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Raccoons are omnivorous,

eating both plant and animal foods. Plant foods include

all types of fruits, berries, nuts, acorns, corn, and

other types of grain. Animal foods are crayfish, clams,

fish, frogs, snails, insects, turtles and their eggs,

mice, rabbits, muskrats, and the eggs and young of

ground-nesting birds and waterfowl. Contrary to popular

myth, raccoons do not always wash their food before

eating, although they frequently play with their food in

water.

Raccoons breed mainly in

February or March, but matings may occur from December

through June, depending on latitude. The gestation

period is about 63 days. Most litters are born in April

or May but some late-breeding females may not give birth

until June, July, or August. Only 1 litter of young is

raised per year. Average litter size is 3 to 5. The

young first open their eyes at about 3 weeks of age.

Young raccoons are weaned sometime between 2 and 4

months of age.

Raccoons are nocturnal.

Adult males occupy areas of about 3 to 20 square miles

(8 to 52 km2), compared to about 1 to 6 square miles (3

to 16 km2) for females. Adult males tend to be

territorial and their ranges overlap very little.

Raccoons do not truly hibernate, but they do “hole up”

in dens and become inactive during severe winter

weather. In the southern United States they may be

inactive for only a day or two at a time, whereas in the

north this period of inactivity may extend for weeks or

months. In northern areas, raccoons may lose up to half

their fall body weight during winter as they utilize

stored body fat.

Raccoon populations

consist of a high proportion of young animals, with

one-half to three-fourths of fall populations normally

composed of animals less than 1 year in age. Raccoons

may live as long as 12 years in the wild, but such

animals are extremely rare.

Usually less than half of

the females will breed the year after their birth,

whereas most adult females normally breed every year.

Family groups of raccoons

usually remain together for the first year and the young

will often den for the winter with the adult female. The

family gradually separates during the following spring

and the young become independent.

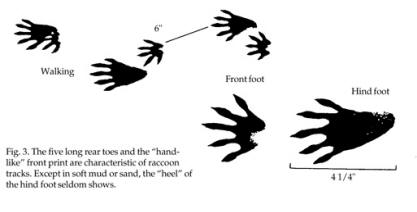

Damage and Damage Identification

Raccoons may cause damage

or nuisance problems in a variety of ways, and their

distinctive tracks (Fig. 3) often provide evidence of

their involvement in damage situations.

Raccoons occasionally kill

poultry and leave distinctive signs. The heads of adult

birds are usually bitten off and left some distance from

the body. The crop and breast may be torn and chewed,

the entrails sometimes eaten, and bits of flesh left

near water. Young poultry in pens or cages may be killed

or injured by raccoons reaching through the wire and

attempting to pull the birds back through the mesh. Legs

or feet of the young birds may be missing. Eggs may be

removed completely from nests or eaten on the spot with

only the heavily cracked shell remaining. The lines of

fracture will normally be along the long axis of the

egg, and the nest materials are often disturbed.

Raccoons can also destroy bird nests in artificial

nesting structures such as bluebird and wood duck nest

boxes.

Raccoons can cause

considerable damage to garden or truck crops,

particularly sweet corn. Raccoon damage to sweet corn is

characterized by many partially eaten ears with the

husks pulled back. Stalks may also be broken as raccoons

climb to get at the ears. Raccoons damage watermelons by

digging a small hole in the melon and then raking out

the contents with a front paw.

Raccoons cause damage or

nuisance problems around houses and outbuildings when

they seek to gain entrance to attics or chimneys or when

they raid garbage in search of food. In many urban or

suburban areas, raccoons are learning that uncapped

chimneys make very adequate substitutes for more

traditional hollow trees for use as denning sites,

particularly in spring. In extreme cases, raccoons may

tear off shingles or facia boards in order to gain

access to an attic or wall space.

Raccoons also can be a

considerable nuisance when they roll up freshly laid sod

in search of earthworms and grubs. They may return

repeatedly and roll up extensive areas of sod on

successive nights. This behavior is particularly common

in mid- to late summer as young raccoons are learning to

forage for themselves, and during periods of dry weather

when other food sources may be less available.

The incidence of reported

rabies in raccoons and other wildlife has increased

dramatically over the past 30 years. Raccoons have

recently been identified as the major wildlife host of

rabies in the United States, primarily due to increased

prevalence in the eastern United States.

Legal Status

Raccoons are protected

furbearers in most states, with seasons established for

running, hunting, or trapping. Most states, however,

have provisions for landowners to control furbearers

that are damaging their property. Check with your state

wildlife agency before using any lethal controls.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Exclusion, if feasible, is

usually the best method of coping with raccoon damage.

Poultry damage generally

can be prevented by excluding the raccoons with tightly

covered doors and windows on buildings or mesh-wire

fences with an overhang surrounding poultry yards.

Raccoons are excellent climbers and are capable of

gaining access by climbing conventional fences or by

using overhanging limbs to bypass the fence. A “hot

wire” from an electric fence charger at the top of the

fence will greatly increase the effectiveness of a fence

for excluding raccoons.

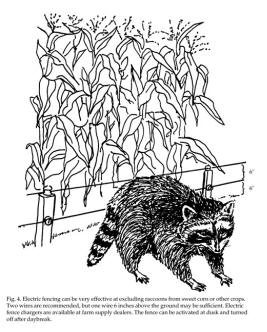

Damage to sweet corn or

watermelons can most effectively be stopped by excluding

raccoons with a single or double hot-wire arrangement

(Fig. 4). The fence should be turned on in the evening

before dusk, and turned off after daybreak. Electric

fences should be used with care and appropriate caution

signs installed. Wrapping filament tape around ripening

ears of corn (Fig. 5) or placing plastic bags over the

ears is an effective method of reducing raccoon damage

to sweet corn. In general, tape or fencing is more

effective than bagging. When using tape, it is important

to apply the type with glass-yarn filaments embedded

within so that the

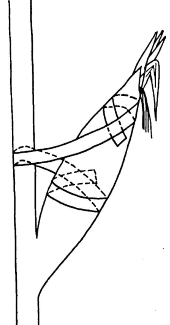

Fig. 5. Wrapping a ripening ear of sweet corn with

reinforced filament tape as shown can reduce raccoon

damage by 70% to 80%. It is important that each loop of

the tape be wrapped over itself so that it forms a

closed loop that cannot be ripped open by the raccoon.

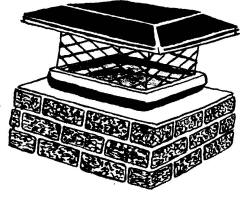

Fig. 6. A cap or exclusion

device will keep raccoons and other animals out of

chimneys. These are available commercially and should be

made of heavy material. Tightly clamp or fasten them to

chimneys to prevent raccoons from pulling or tearing

them off.

Raccoons cannot tear

through the tape. Taping is more labor-intensive than

fencing, but may be more practical and acceptable for

small backyard gardens.

Store garbage in metal or

tough plastic containers with tight-fitting lids to

discourage raccoons from raiding garbage cans. If lids

do not fit tightly, it may be necessary to wire, weight,

or clamp them down to prevent raccoons from lifting the

lid to get at garbage. Secure cans to a rack or tie them

to a support to prevent raccoons from tipping them over.

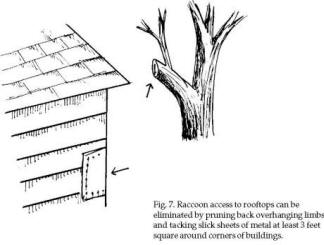

Prevent raccoon access to

chimneys by securely fastening a commercial cap of sheet

metal and heavy screen over the top of the chimney (Fig. 6). Raccoon

access to rooftops can be limited by removing

overhanging branches and by wrapping and nailing sheets

of slick metal at least 3 feet (90 cm) square around

corners of buildings. This prevents raccoons from being

able to get a toehold for climbing (Fig. 7). While this

method may be practical for outbuildings, it is

unsightly and generally unacceptable for homes. It is

more practical to cover chimneys or other areas

attracting raccoons to the rooftop or to remove the

offending individual animals than to completely exclude

them from the roof.

screen over the top of the chimney (Fig. 6). Raccoon

access to rooftops can be limited by removing

overhanging branches and by wrapping and nailing sheets

of slick metal at least 3 feet (90 cm) square around

corners of buildings. This prevents raccoons from being

able to get a toehold for climbing (Fig. 7). While this

method may be practical for outbuildings, it is

unsightly and generally unacceptable for homes. It is

more practical to cover chimneys or other areas

attracting raccoons to the rooftop or to remove the

offending individual animals than to completely exclude

them from the roof.

Homeowners attempting to

exclude or remove raccoons in the spring and summer

should be aware of the possibility that young may also

be present.

Do not complete exclusion

procedures until you are certain that all raccoons have

been removed from or have left the exclusion area.

Raccoons frequently will use uncapped chimneys as natal

den sites, raising the young on the smoke shelf or the

top of the fireplace box until weaning. Homeowners with

the patience to wait out several weeks of scratching,

rustling, and chirring sounds will normally be rewarded

by the mother raccoon moving the young from the chimney

at the time she begins to wean them. Homeowners with

less patience can often contact a pest removal or

chimney sweep service to physically remove the raccoons.

In either case, raccoon exclusion procedures should be

completed immediately after the animals have left or

been removed.

Habitat Modification

There are no practical

means of modifying habitat to reduce raccoon

depredations, other than removing any obvious sources of

food or shelter which may be attracting the raccoons to

the premises. Raccoons forage over wide areas, and

anything other than local habitat modification to reduce

raccoon numbers is not a desirable technique for

reducing damage.

Raccoons sometimes will

roll up freshly laid sod in search of worms or grubs. If

sodded areas are not extensive, it may be possible to

pin the rolls down with long wire pins, wooden stakes,

or nylon netting until the grass can take root,

especially if the damage is restricted to only a portion

of the yard, such as a shaded area where the grass is

slower to take root. In more rural areas, use of

electric fences may be effective (see section on

exclusion). Because the sod-turning behavior is most

prevalent in mid-to late summer when family groups of

raccoons are learning to forage, homeowners may be able

to avoid problems by having the sod installed in spring

or early summer. In most cases, however, removal of the

problem raccoons is usually necessary.

Frightening Frightening

Although several

techniques have been used to frighten away raccoons,

particularly in sweet corn patches, none has been proven

to be effective over a long period of time. These

techniques have included the use of lights, radios,

dogs, scarecrows, plastic or cloth streamers, aluminum

pie pans, tin can lids, and plastic windmills. All of

these may have some temporary effectiveness in deterring

raccoons, but none will provide adequate long-term

protection in most situations.

Repellents, Toxicants,

and Fumigants

There are no repellents,

toxicants, or fumigants currently registered for raccoon

control.

Trapping

Raccoons are relatively

easy to catch in traps, but it takes a sturdy trap to

hold one. For homeowners with pets, a live or cage-type

trap (Fig. 8) is usually the preferable alternative to a

leghold trap. Traps should be at least 10 x 12 x 32

inches (25.4 x 30.5 x 81.3 cm) and well-constructed with

heavy materials. They can be baited with canned

fish-flavored cat food, sardines, fish, or chicken.

Place a pile of bait behind the treadle and scatter a

few small bits of bait outside the opening of the trap

and just inside the entrance. Traps with a single door

should be placed with the back against a wall, tree, or

other object. The back portion of the trap should be

tightly screened with one-half inch (1.3 cm) or smaller

mesh wire to prevent raccoons from reaching through the

wire to pull out the bait.

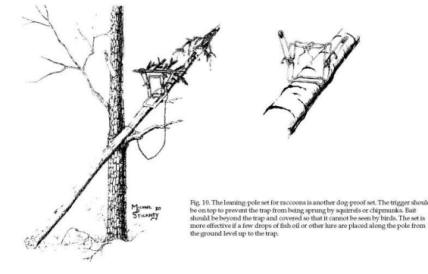

Conibear®-type

body-gripping traps are effective for raccoons and can

be used in natural or artificial cubbies or boxes.

Because these traps do not allow for selective release

of nontarget catches, they should not be used in areas

where risk of nontarget capture is high. Box or leghold

traps should be used in those situations instead. It is

possible, however, to use body-grip-ping traps in boxes

or on leaning poles so that they are inaccessible to

dogs (Figs. 9 and 10). Check local state laws for

restrictions regarding use of Conibear®-type traps out

of water.

Raccoons also can be

captured in foothold traps. Use a No. 1 or No. 1 1/2

coilspring or stoploss trap fastened to a drag such as a tree limb 6 to 8 feet (1.8

to 2.4 m) long. For water sets, use a drowning wire that

leads to deep water. The D-P trap and Egg trap are new

foot-holding devices that are highly selective,

dog-proof, and show promise for reducing trap-related

injury. They are available from trapping supply outlets.

fastened to a drag such as a tree limb 6 to 8 feet (1.8

to 2.4 m) long. For water sets, use a drowning wire that

leads to deep water. The D-P trap and Egg trap are new

foot-holding devices that are highly selective,

dog-proof, and show promise for reducing trap-related

injury. They are available from trapping supply outlets.

Fig. 8. A cage-type live

trap, although bulky and expensive, is often the best

choice for removing raccoons near houses or buildings

where there is a likelihood of capturing dogs or cats.

Fig. 9. A “raccoon box” is

suspended 6 inches above the ground and is equipped with

a Conibear®-type trap. Suspended at this level, this set

is dog-proof.

The “pocket set” is very

effective for raccoons, and is made along the water’s

edge where at least a slight bank is present (Fig. 11).

Dig a hole 3 to 6 inches (7.6 to 15.2 cm) in diameter

horizontally back into the bank at least 10 to 12 inches

(25.4 to 30.5 cm). The bottom 2 inches (5.1 cm) of the

hole should be below the water level. Place a bait or

lure (fish, frog, anise oil, honey) in the back of the

hole, above the water level. Set the trap (a No. 1 or 1

1/2 coilspring, doublejaw or stoploss is recommended)

below the water level in front of or just inside the

opening. The trap should be tied to a movable drag or

attached with a one-way slide to a drowning wire leading

to deep water.

Dirt-hole sets (Fig. 12)

are effective for raccoons. Place a bait or lure in a

small hole and conceal the trap under a light covering

of soil in front of the hole. A No. 1 or 1 1/2

coilspring trap is recommended for this set. It is

important to use a small piece of clean cloth, light

plastic, or a wad of dry grass to prevent soil from

getting under the round pan of the trap and keeping it

from going down. If this precaution is not taken, the

trap may not go off.

Shooting

Raccoons are seldom seen

during the day because of their nocturnal habits.

Shooting raccoons can be effective at night with proper

lighting. Trained dogs can be used to tree the raccoons

first. A .22-caliber rifle will effectively kill treed

raccoons. Many states have restrictions on the use of

artificial light to spot and shoot raccoons at night,

and shooting is prohibited in most towns and cities. It

is advisable to check with state and local authorities

before using any lethal controls for raccoons.

Many states have

restrictions on the use of artificial light to spot and

shoot raccoons at night, and shooting is prohibited in

most towns and cities. It is advisable to check with

state and local authorities before using any lethal

controls for raccoons.

Economics of Damage and

Control Statistics are unavailable on the amount of

economic damage caused by raccoons, but the damage may

be offset by their positive economic and aesthetic

values. In 1982 to 1983, raccoons were by far the most

valuable furbearer to hunters and trappers in the United

States; an estimated 4.8 million raccoons worth $88

million were harvested. Raccoons also provide recreation

for hunters, trappers, and use of artificial light to

spot and shoot people who enjoy watching them. Although

raccoon damage and nuisance problems can be locally

severe, widespread raccoon control programs authorities

before using any lethal con-are not justifiable, except

perhaps to prevent the spread of raccoon rabies. From a

cost-benefit and ecological standpoint, prevention

practices and specific control of problem individuals or

localized populations are the most desirable

alternatives.

Acknowledgments

Although information for

this section came from a variety of sources, I am

particularly indebted to Eric Fritzell of the University

of Missouri, who provided a great deal of recently

published and unpublished information on raccoons in the

central United States. Information on damage

identification was adapted from Dolbeer et al. 1994.

Figures 1 through 3 from

Schwartz and Schwartz (1981).

Figures 4, 6, and 7 by

Jill Sack Johnson.

Figure 5 from Conover

(1987).

Figures 8, 9, and 10 by

Michael D. Stickney, from the New York Department of

Environmental Conservation publication Trapping

Furbearers, Student Manual (1980), by R. Howard, L.

Berchielli, G. Parsons, and M. Brown. The figures are

copyrighted and are used with permission.

Figure 11 by J. Tom

Parker, from Trapping Furbearers: Managing and Using a

Renewable Natural Resource, a Cornell University

publication by R. Howard and J. Kelly (1976). Used with

permission.

Figure 12 adapted from

Controlling Problem Red Fox by F. R. Henderson (1973),

Cooperative Extension Service, Kansas State University,

Manhattan.

For Additional Information

Conover, M. R. 1987. Reducing raccoon and bird damage to

small corn plots. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 15:268-272.

Dolbeer, R. A., N. R.

Holler, and D. W. Hawthorne. 1994. Identification and

control of wildlife damage. Pages 474-506 in T. A.

Bookhout, ed. Research and management techniques for

wildlife and habitats. The Wildl. Soc. Bethesda,

Maryland.

Kaufmann, J. H. 1982.

Raccoon and allies. Pages 567-585 in J. A. Chapman and

G. A. Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North America:

biology, management and economics. The Johns Hopkins

Univ. Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri, rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp.

Sanderson, G. C. 1987.

Raccoon. Pages 486-499 in M. Novak, J. A. Baker, M. E.

Obbard, and B. Malloch, eds. Wild furbearer management

and conservation in North America. Ontario Trappers

Assoc., North Bay.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom; Robert

M. Timm; Gary E. Larson;

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|