|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: Polar Bears |

|

|

Identification

The polar bear (Fig. 1) is

the largest member of the family Ursidae. Males are

approximately twice the size of females. On average,

adult males weigh 500 to 900 pounds (250 to 400 kg),

depending on the time of year. An exceptionally large

individual might reach 1,320 to 1,760 pounds (600 to 800

kg). Adult females weigh 330 to 550 pounds (150 to 250

kg) on average, although a pregnant female just prior to

going into a maternity den could be double that weight.

Polar bears have a heavy

build overall, large feet, and a longer neck relative to

their body size than other species of bears. The fur is

white, but the shade may vary among white, yellow, grey,

or almost brown, depending on the time of year or light

conditions. The pelage consists of a thick underfur

about 2 inches (5 cm) in length and guard hairs about 6

inches (15 cm) long. Polar bears have a plantigrade gait

and five toes on each paw with short, sharp,

nonretractable claws. Females normally have four

functional mammae. The vitamin A content of the liver

ranges between 15,000 and 30,000 units per gram and is

toxic to humans if consumed in any quantity.

Range Range

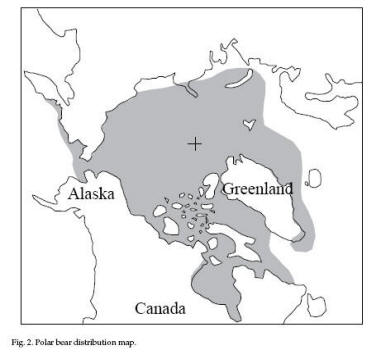

Polar bears are

distributed throughout the circumpolar Arctic. In North

America, their range extends from the Canadian Arctic

Islands and the permanent multiyear pack ice of the

Arctic Ocean to the Labrador coast and southern James

Bay. The southern limit of their distribution in open

ocean areas such as the Bering Sea or Davis Strait

varies depending on how far south seasonal pack ice

moves during the winter (Fig. 2).

Habitat

From freezeup in the fall,

through the winter, and until breakup in the spring,

polar bears are dispersed over the annual ice along the

mainland coast of continental North America, the

inter-island channels, and the shore lead and polynia

systems associated with them. Polar bears are not

abundant in areas of extensive multiyear ice, probably

because of the low density of seals there.

Polar bears use a variety

of habitats when hunting seals, including stable

fast-ice with deep snowdrifts along pressure ridges that

are suitable for seal birth lairs and breathing holes,

the floe edge where leads are greater than 1 mile wide

(1.6 km), and areas of moving ice with seven-eighths or

more of ice cover. Bears may be near the coast or far

offshore, depending on the distribution of these

habitats. Ringed seals (Phoca hispida) and sometimes

bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus) maintain their

breathing holes from freezeup in the fall to breakup in

the spring. Bears can hunt more successfully in areas

where wind, water current, or tidal action cause the ice

to continually crack and subsequently refreeze.

During winter, bears are

less abundant in deep bays or fiords in which expanses

of flat annual ice have consolidated through the winter.

In places where the snow cover in the fiords is deep,

large numbers of ringed seals give birth to their pups

in subnivean lairs in the spring. Consequently, polar

bears in general, but especially females with newborn

cubs, move into such areas in April and May to hunt seal

pups.

During summer, the

response of the bears to the annual ice melts varies

depending on where they live. Bears in the Beaufort and

Chukchi seas may move hundreds of miles to stay with the

ice. Bears in the Canadian arctic archipelago make

seasonal movements of varying distances depending on ice

conditions. Polar bears travel seasonally to remain

where ice is present because they depend on the sea ice

for most of their hunting.

In Hudson Bay, James Bay,

parts of Foxe Basin, and the southeastern coast of

Baffin Island, the ice melts completely in the summer

and there are no alternate areas with ice close enough

to migrate to. In these areas the bears may be forced

ashore as early as the end of July to fast on land until

November. Some bears remain along the coast while others

move inland to rest in pits in snow banks or in earth

dens in areas of discontinuous permafrost. By late

September or early October, bears that spent the summer

on land tend to move toward the coast in anticipation of

freezeup. Many conflicts with people occur in the fall

when bears are waiting along coastal areas for the sea

ice to form.

Food Habits

Polar bears feed on ringed

seals and to a lesser degree on bearded seals. About

half of the ringed seals killed during the spring and

early summer are the young of the year. These young

seals are up to 50% fat by weight and are probably easy

to catch because they are vulnerable and inexperienced.

Less frequently taken prey include walrus (Odobenus

rosmarus), white whales (Delphinapterus leucas),

narwhals (Monodon monoceros), and harp seals (Pagophilus

groenlandicus). Polar bears also eat small mammals, bird

eggs, sea weed, grass, and other vegetation, although

these food sources are much less common and probably not

significant.

Polar bears are curious

animals and will investigate human settlements and

garbage. They have been observed to ingest a wide range

of indigestible and hazardous materials, such as plastic

bags, styrofoam, car batteries, ethylene glycol, and

hydraulic fluid.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Polar bears mate on the

sea ice in April and May. Implantation of the embryo is

delayed until the following September. The adult sex

ratio is even, but because females normally keep their

young for about 2 1/2 years, they usually mate only once

every 3 years. This creates a functional sex ratio of

three or more males per female that results in intensive

competition among males for access to estrus females.

Maternity dens are usually

dug in deep snow banks on steep slopes or stream banks

near the sea by late October or early November,

depending on the availability of snow. In the Beaufort

Sea, a large proportion of the females den on the

multiyear pack ice several hundred miles (km) offshore.

On the Ontario and Manitoba coasts of Hudson Bay, female

polar bears may have their maternity dens 30 to 60 miles

(50 to 100 km) or more inland, though this is quite

unusual elsewhere in polar bear range.

Pregnant females normally

have 2 young between about late November and early

January. At birth, cubs weigh about 1.3 pounds (0.6 kg),

have a covering of fine hair, and are blind. They are

nursed inside the den until sometime between the end of

February and the middle of April, depending on latitude.

When the female opens her den, the cubs weigh 22 to 26

pounds (10 to 12 kg). The family remains near the den,

sleeping in it at night or during inclement weather for

up to another 2 weeks while the cubs exercise and

acclimatize to the cold, after which they move to the

sea ice to hunt seals.

The mean age of adults in

a population is 9 to 10 years and average life

expectancy is about 15 to 18 years. Maximum recorded age

of a male in the wild is 29 years. Few male polar bears

live past 20 years because of the intense competition

and aggression among them. The oldest age recorded for a

wild female polar bear is 32 years.

Depending on the age and

sex class, polar bears spend 19% to 25% of their total

time hunting in the spring and 30% to 50% of their time

hunting in the summer. Polar bears capture seals mainly

by stalking them, by waiting for them to surface at a

breathing hole or, in the spring, by digging out seal

pups and sometimes adults from birth lairs beneath the

snow. When a polar bear kills a seal it immediately eats

as much as it can and then leaves. Polar bears do not

cache food and normally only remain with a kill for a

short time. In the case of a large food supply such as a

dead whale or a garbage dump, individual bears may

remain in an area for several days or even weeks.

Polar bears sleep about 7

to 8 hours a day. They tend to be more active at “night”

during the 24-hour daylight that prevails in the summer

months, and to sleep during the day. Within 1 or 2 hours

after feeding, they will usually sleep, regardless of

the time of day. Before sleeping, females with cubs

often move away from areas where other bears are active,

probably to reduce the risk of predation on the cubs by

adult males.

Damage

and Damage Identification

Threat or damage from a

polar bear differs from that of other bears because it

can occur at any time of the year. Conflicts are

commonly referred to as “threat to life or property” (TLP)

or “defense of life or property” (DLP). Although polar

bears are the most predatory of the three North American

bears, their threat to human life has been low.

Historically, northern people (Inu, Inuit, Inuvialuit,

and Inupiat) were aware of the threat posed by polar

bears. Legends and artwork portray conflicts between

northern people and polar bears. In recent times, polar

bears have injured or killed people living and working

in the Arctic. Fleck and Herrero (1988) provide a

detailed discussion of polar bear-people conflicts in

the Northwest Territories and other areas. The

Bear-People Conflict Proceedings (Bromley 1989) includes

several papers on handling and preventing encounters

with bears.

Damage to property can be

serious in the remote and sometimes harsh arctic

environment, where food and shelter may be essential to

survival. Most property damage occurs at small

semipermanent hunting camps, industrial camps, and in

communities. Damage includes destruction of buildings

and their contents, predation of tied dogs, destruction

of snowmobile seats and other plastic or rubber products

or equipment, and raiding of food caches.

Legal Status

Polar bears are protected

in Canada and the United States. In Canada, polar bears

are legally hunted. Seasons, protected categories, and

quotas apply. In Alaska, polar bear hunting is not

legal, but native people may kill animals for

subsistence. In Russia and Svalbard, polar bears are

completely protected. In Greenland, polar bears are

legally harvested by Inuk hunters. Females with cubs in

dens are protected.

Deterring polar bears in

Alaska is restricted to wildlife officers because polar

bears are protected by the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

This policy is being questioned because it does not

allow companies or private individuals to deter a bear

in a problem situation. It is, however, legal for anyone

to shoot a bear in defense of life. In Canada it is

legal for anyone to attempt to deter, and if necessary

destroy, a bear in defense of life or property. Any bear

killed in either jurisdiction must be reported to the

nearest wildlife office.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Preventing Polar

Bear-People Conflicts

Preventing bear-people

conflicts has been given considerable attention in the

Canadian and Alaskan Arctic since the mid-1970s.

Reducing the number of polar bear-people conflicts has

increased the safety of people living and working in the

Arctic and reduced the number of polar bears killed in

problem situations. An active public information and

education program will help inform people how to prevent

bear problems. Most wildlife agencies in bear country

have a variety of public education materials available

that are specifically designed to help people prevent

bear problems and better handle any that may occur.

Special information and training workshops have been

developed by the Department of Renewable Resources,

Northwest Territories, and adopted by wildlife agencies

and industry in other jurisdictions. The workshops

instruct people on how to prevent bear conflicts. Two

publications to assist workshop instructors are

available (Clarkson and Sutterlin 1983, and Clarkson

1986a). The Safety in Bear Country Manual (Bromley 1985,

Graf et al. 1992) has been used as a reference text for

most workshops.

Many bear problems occur

at industry camps and work sites. When designing and

setting up camps, the number of conflicts can be reduced

by considering the potential bear problems. Keeping a

clean camp and reducing the number of attractants will

reduce bear problems. Once a bear has received a food or

garbage reward from a camp, it will quickly associate

the camp with available food. Most bears that are

habituated to human food or garbage are destroyed in a

problem bear situation. To reduce the number of problems

and problem bear deaths, careful planning and

precautions should be taken.

A “Problem Bear Site

Operations Plan” was developed to help industrial

operations better plan and prevent bear problems

(Clarkson et al. 1986b). The plan helps camp safety

officers, team leaders, and managers locate and design

facilities and programs that are site specific. It

contains information and emergency contact telephone

numbers, site design, personnel responsibilities, and

techniques to detect and deter bears. The plan can be

included in the Safety in Bear Country Manual as an

additional chapter. Problem Bear Site Operation Plans

have been developed for polar bear concerns at the

arctic weather stations and for oil exploration

activities in the Beaufort Sea. Each plan deals with

being prepared for and preventing polar bear problems at

specific sites.

Avoiding and responding to

close encounters with polar bears is addressed by

Bromley (1985), Fleck and Herrero (1988), Stirling

(1988a), and Graf et al. (1992). While each polar bear

encounter is different, the chance of a serious or fatal

bear problem can be reduced by keeping alert and being

informed and prepared to deal with any bear problems

that may arise.

Exclusion Exclusion

Heavy woven-wire fences

are effective in keeping bears out of an area. Fences

must be constructed of sturdy materials and properly

maintained to prevent bears from entering the exclosure.

The fence should be a minimum of 6 feet (2 m) high, and

the bottom should be secured to the ground or a cement

foundation to prevent bears from lifting the fence and

crawling under the wire. Keep fence gates closed when

not in use to prevent bears from entering the area.

Electric fences have been

tested on polar bears with limited success; grounding

problems during winter months have been the primary

obstacle. Davis and Rockwell (1986) describe an electric

fence they used to protect a camp during the summer

months along the Hudson Bay coast.

The use of high metal

platforms, such as oil rig caissons, or offshore

drilling ships, prevents bears from getting access to

work and living areas. Sturdy metal buildings and iron

bar cages have been successfully used to store food and

equipment, and prevent polar bear access.

Cultural Methods

Regular snow removal from

work and living areas in polar bear habitat will help

make these sites safer by reducing potential hiding

spots and increasing visibility for personnel. Install

lighting around the work site to increase visibility and

staff safety. Proper design and set-up of work and

living sites will help reduce potential problems.

Regular camp maintenance and proper handling and storage

of food, wastes, and oil products will help reduce bear

problems.

Deterrents and Frightening

Devices

Nonlethal deterrents are

used on polar bears in an attempt to scare them away

rather than destroy them. Deterrents range from

snowmobiles and vehicles to 12-gauge plastic slugs and

cracker shells. Choosing an appropriate deterrent will

depend on the type of problem and specific location

(Table 1). Regardless of the type of deterrent used, all

encounters with bears should be supported by an

additional person equipped with a loaded firearm.

Graf et al. (1992)

reviewed several deterrents that are useful for polar

bears. Clarkson (1989) recommends the use of a 12-gauge

shotgun and a “three-slug system” (cracker shell,

plastic slug, and lead slug). Deter bears from a site as

soon as they are seen in the area, to prevent them from

approaching closer and receiving some type of food or

garbage reward. Figure 3 identifies the appropriate

distances for deterring versus destroying a bear. Each

bear deterrent situation is different, and depends on

the bear’s behavior and safety options available at the

site. When deterring a bear with a plastic slug, aim for

the large muscle mass area in the hind quarters (Fig.

4). The neck and front shoulders should be avoided to

minimize the risk of hitting and damaging an eye.

Detection Systems

Detecting a polar bear

that is approaching a work or living area is an

important part of handling bear problems. Bear detection

systems range from a simple tripwire to more technical

electronic monitoring devices (Table 2). If a bear is

approaching a work or living area, the personnel on site

should have time first to ensure their safety and second

to prepare to deter the bear. Detection systems must be

properly installed and maintained to be effective. If

bear problems are rare, a system that is too technical

or difficult to maintain will soon be neglected. Bear

monitors and dogs should have previous experience with

bears. An experienced bear dog can act both as a

detection and deterrent system.

Repellents

Capsaicin (oleoresin of

capsicum or concentrated red pepper) spray has been

tested and used on black and grizzly bears (Hunt 1984),

but has not yet been tested on polar bears. It may

become more popular where restrictions on firearms are

in place. Capsaicin needs to be scientifically tested

before it can be formally recommended for polar bear

protection.

Toxicants

No toxicants are

registered for use on polar bears.

Fumigants

No fumigants are

registered for use on polar bears.

Trapping

Live traps used to capture

polar bears include culvert or barrel traps and foot

snares. Both have been used to capture all three bear

species in North America. The culvert trap has been used

to capture polar bears at Churchill, Manitoba, and in

the eastern Northwest Territories. It can also be used

for short-term holding and transporting of captured

polar bears. Foot snares were used in polar bear

research in the early 1970s and are useful in some

situations today. A detailed description of using the

culvert trap and foot snare is found in the Black Bears

chapter in this handbook. In the early to mid-1900s,

large leghold traps were used along the Arctic coast.

These are no longer used today.

Shooting

Unfortunately, some

bear-people conflicts require that problem bears be

shot. Polar bears can be aggressive in attempting to

obtain food, especially if they are in poor condition

and near starving. If it is necessary to destroy a polar

bear, it should be done as efficiently and humanely as

possible. The 12-gauge pump action shotgun with lead

slugs is an effective weapon for destroying a bear at

close range (less than 100 feet [30 m]). It can also be

used to deter a polar bear. High-powered rifles of

.30-06 or larger caliber are also effective in

destroying bears. A rifle used for bear protection

should be equipped with open sights for close-range use.

Generally, if a bear is

beyond 150 feet (45 m), destroying it is not necessary

because the bear can be deterred before it comes closer.

If it is necessary to destroy a bear beyond 100 feet (30

m), a high-powered rifle will be more accurate and have

more penetration energy. Whether a shotgun or rifle is

used, bears should be shot in the chest/vital organ area

(Fig. 4). Handguns are not recommended for bear

protection or for destroying problem bears. Proper

training and practice is necessary to effectively use a

firearm for bear protection or for destroying a bear.

Other Methods

Drugging/Immobilization.

Polar bears are often immobilized in problem situations.

Bears can be drugged while free ranging by darting them

from the ground or from a helicopter, or darting after

capture in a culvert trap or foot snare. Darts can be

fired from a rifle or pistol. A jab stick can be used to

immobilize bears captured in a culvert trap, but is not

recommended for bears in a foot snare. Drugging/Immobilization.

Polar bears are often immobilized in problem situations.

Bears can be drugged while free ranging by darting them

from the ground or from a helicopter, or darting after

capture in a culvert trap or foot snare. Darts can be

fired from a rifle or pistol. A jab stick can be used to

immobilize bears captured in a culvert trap, but is not

recommended for bears in a foot snare.

Darting from a helicopter

(Bell 206 Jet Ranger or similar size), has been used for

research and problem bear management. The helicopter

should be equipped with a shooting window and have sling

capabilities for moving bears. The helicopter should

slowly approach the bear from behind at an altitude of

20 to 30 feet (6 to 10 m). Shooting distance from a

helicopter is usually less than 30 feet (10 m). Bears

should be darted in the large muscle areas of the neck,

shoulder, or upper midback. Several immobilizing drugs

have been used on polar bears in the past, however,

Telazol is presently considered the most effective.

Telazol is a safe and predictable drug to work with

because there is a wide range of tolerance to high

dosages, the reactions of darted bears can be easily

interpreted, and the bears are able to thermoregulate

while immobilized. Dosages of 8 to 9 mg/kg or greater

are usually necessary to fully immobilize a polar bear

for measuring and tagging. Immobilization time for adult

bears depends on the injection site and weight of the

bear. On the average, a bear will be immobilized in 4 to

5 minutes after the first injection of Telazol. Cubs of

the year can be immobilized by hand or with a jabstick

after being captured on or near their immobilized

mother.

Holding,

Transporting, and Relocating. Problem polar

bears that are captured or immobilized and not destroyed

are usually held in a culvert trap or other suitable

facility. Bears can be transported from a problem site

with a culvert trap and released at another location if

a road system exists. Road systems are limited in the

arctic and relocating problem bears with culvert traps

is usually not an effective option. In most cases,

captured and immobilized bears need to be relocated by

helicopter. Take precautions to ensure that bears are

not injured or suffering from hyperthermia when

transporting them in a cargo net below a helicopter.

In Churchill, Manitoba,

polar bears are captured in or near the town limits,

held in a polar bear holding facility and then flown out

to an area north of Churchill and released. Capturing

and holding the bears in the “polar bear jail” prevents

these bears from causing problems while they are waiting

for the ice to form on Hudson Bay. Bears kept in a

holding facility can be given water, but food is not

recommended because the bears may begin to associate

people and the holding facility with food. Although an

expensive program, the polar bear jail at Churchill has

reduced the number of polar bear problems and polar bear

mortalities.

Relocating problem bears

usually does not solve the problem since they often

return, sometimes from considerable distances. Polar

bears that are waiting along a coastline for ice to form

should be moved in the general direction they would

normally travel. Most of the polar bears released north

of Churchill travel out on the sea ice and do not return

to the townsite.

Economics of Damage and Control

No specific studies or

reports have documented the economic costs of polar bear

damage in the Arctic. Past polar bear problems have

ranged in cost from nothing to several thousands of

dollars. With the remote locations of camps and

communities and the expense of transporting food and

products in the Arctic, replacement costs are high. Lost

work time of personnel and programs can also be

substantial because of polar bear problems. In September

1983, Esso Resources Canada had to suspend drilling

until a wildlife officer could drug and remove a bear

that had happened onto the artificial island, costing

Esso about $125,000. A similar incident occurred in

1985, and cost Esso approximately $250,000 in lost work

time.

Hiring bear monitors can

cost up to $250 per day to protect personnel, a camp, or

an industrial site from polar bears. The cost of

government staff and programs that are responsible for

handling polar bear problems will depend on the number

of problems. Churchill, Manitoba, has the most intensive

government program to handle polar bear problems. This

program costs the Manitoba government approximately

$120,000 per year (M. Shoesmith, pers. commun.).

Purchasing detection and

deterrent equipment and educating people on the proper

procedures to prevent and handle bear problems will cost

companies and agencies. These costs, however, are

minimal when compared to personnel safety, replacement

costs of property in the Arctic, and long-term polar

bear conservation concerns.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge

the following for their continued support of our

research on bears in general, and polar bears in

particular: the Northwest Territories Department of

Renewable Resources, the Canadian Wildlife Service,

Polar Continental Shelf Project, Manitoba Department of

Natural Resources, World Wildlife Fund (Canada),

Northern Oil and Gas Assessment Program, and the Natural

Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. All

people, organizations, government departments, and

industry previously involved in the Northwest

Territories’ “Safety in Bear Country Program” are

thanked for their past concern and support.

L. Graf and K. Embelton

assisted in word-processing and editing.

Tables 1 and 2 were

adapted from Graf et al. (1992).

Figure 1 drawn by Clint

Chapman, University of Nebraska.

Figure 2 was adapted from

Sterling (1988) by Dave Thornhill, University of

Nebraska.

Figures 3 and 4 are from

Clarkson (1989).

For Additional Information

Amstrup, S. E. 1986.

Research on polar bears in Alaska, 1983-1985. Proc.

Working Meeting of the IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialist

Group. 9:85-108.

Arco Alaska, Inc. 1990.

Fireweed No. 1 exploratory well. Polar Bear/Personnel

Encounter and Monitoring Plans. 16 pp.

Banfield, A. W. F. 1974.

The mammals of Canada. Univ. Toronto Press, Toronto. 438

pp.

Bromley, M. 1985. Safety

in bear country: a reference manual. Northwest Territ.

Dep. Renew. Resour., Yellowknife. 120 pp.

Bromley, M., ed. 1989.

Bear-people conflicts. Proc. Symp. Manage. Strategies

Northwest Territ. Dep. Renew. Resour., Yellowknife. 246

pp.

Calvert, W., I. Stirling,

M. Taylor, L. J. Lee, G. B. Kolenosky, S. Kearney, M.

Crete, B. Smith, and S. Luttich. 1991. Polar bear

management in Canada 1985-87. Rep. to the IUCN Polar

Bear Specialist Group. Proc. IUCN/SSC Polar Bear

Specialists Group. IUCN Report No. 7:1-10.

Clarkson, P. L. 1986a.

Safety in bear country instructors’ guide. Northwest

Territ. Dep. Renew. Resour., Yellowknife. 32 pp.

Clarkson, P. L. 1986b.

Eureka and Mould Bay weather stations problem bear site

evaluation and recommendation. Northwest Territ. Dep.

Renew. Resour., Yellowknife. 42 pp.

Clarkson, P. L. 1989. The

twelve-gauge shotgun: a bear deterrent and protection

weapon. Pages 55-59 in M. Bromley, ed. Bear-people

conflicts. Proc. Sym. Manage. Strategies. Northwest

Territ. Dep. Renew. Resour., Yellowknife.

Clarkson, P. L., and P.

Gray. 1989. Presenting safety in bear country

information to industry and the public. Pages 203-207 in

M. Bromley, ed. Bear-people conflicts. Proc. Sym.

Manage. Strategies. Northwest Territ. Dep. Renew. Resour.,

Yellowknife.

Clarkson, P. L., P. A.

Gray, J. E. McComiskey, L. R. Quaife, and J. G. Ward.

1986a. Managing bear problems in northern development

areas. Northern Hydrocarbon Development Environment

Problem Solving. Proc. Ann. Meeting Int. Soc. Petroleum

Ind. Biol. 10:47-56.

Clarkson, P. L., G. E.

Henderson, and P. Kraft. 1986b. Problem bear site

operation plans. Northwest Territ. Dep. Renew. Resour.,

Yellowknife. 12 pp.

Clarkson, P. L., and L.

Sutterlin. 1983. Bear essentials: a source book and

guide to planning bear education programmes. Faculty

Environ. Design, Univ. Calgary. 69 pp.

Davis, J. C., and R. F.

Rockwell. 1986. An electric fence to deter polar bears.

Wild. Soc. Bull. 14:406-409.

DeMaster, D. P., and I.

Stirling. 1981. Ursus maritimus. Mammal. Species

145:1-7.

Fleck, S., and S. Herrero.

1988. Polar bear conflicts with humans. Contract Rep.

No. 3. Northwest Territ. Dep. Renew. Resour.,

Yellowknife. 155 pp.

Graf, L. H., P. L.

Clarkson, and J. A. Wagy. 1992. Safety in bear country:

a reference manual, rev. ed. Northwest Territ. Dep.

Renew. Resour., Yellowknife. 135 pp.

Gray, P. A., and M.

Sutherland. 1989. A review of detection systems. Pages

61-67 in M. Bromley, ed. Bear-people conflicts. Proc.

Symp. Manage. Strategies. Northwest Territ. Dep. Renew.

Resour., Yellowknife.

Hunt, C. L. 1984.

Behavioral responses of bears to tests of repellents,

deterrents, and aversive conditioning. M.S. Thesis.

Montana State Univ., Bozeman. 136 pp.

Hygnstrom, S. E. 1994.

Black bears. in S. E. Hygnstrom, R. M. Timm and G. E.

Larson, eds. Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage.

Coop. Ext., Univ. Nebraska, Lincoln.

Lewis, R. W., and J. A.

Lentfer. 1967. The vitamin A content of polar bear

liver: range and variability. Compar. Biochem. Physiol.

22:923-926.

Lunn, N. J., and I.

Stirling. 1985. The significance of supplemental food to

polar bears during the ice-free period of Hudson Bay.

Can. J. Zool. 63:2291-2297.

Meehan, W. R., and J. F.

Thilenius. 1983. Safety in bear country: protective

measures and bullet performance at short range. US Dep.

Agric. For. Serv. Gen. Rep PNW-152. 16 pp.

Rodahl, K. 1949. Toxicity

of polar bear liver. Nature 164:530.

Ramsay, M. A., and I.

Stirling. 1988. Reproductive biology and ecology of

female polar bears Ursus maritimus. J. Zool. London.

214:601-634.

Schliebe, S. 1991. Polar

bear management in Alaska. Report to the IUCN Polar Bear

Specialist Group. Proc. IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialists

Group. IUCN Rept. No. 7:62-69.

Schweinsburg, R. E., L. J.

Lee, and P. B. Latour. 1982. Distribution, movement, and

abundance of polar bears in Lancaster Sound, Northwest

Territories. Arctic 35:159-169.

Stenhouse, G. B, L. J.

Lee, and K. G. Poole. 1988. Some characteristics of

polar bears killed during conflicts with humans in the

Northwest Territories. Arctic 41:275-378.

Stirling, I. 1975. Summary

of a fatality involving a polar bear attack in the

Mackenzie Delta, January 1975. Can. Wildl. Serv. Polar

Bear Proj. Spec. Rep. 89. 2 pp.

Stirling,

I. 1988a. Polar bears. Univ. Michigan Press., Ann Arbor.

220 pp.

Stirling,

I. 1988b. Attraction of polar bears Ursus maritimus to

offshore drilling sites in the eastern Beaufort Sea.

Polar Record 24(148):1-8.

Stirling,

I., and A. E. Derocher. 1990. Factors affecting the

evolution and behavioural ecology of the modern bears.

Int.. Conf. Bear Res. Manage. 8:189-204.

Stirling,

I., and M. A. Ramsay. 1986. Polar bears in Hudson Bay

and Foxe Basin: present knowledge and research

opportunities. Pages 341-354 in I. P. Martini, ed.

Canadian Inland Seas. Elsevier Sci. Publ., Amsterdam.

494 pp.

Stirling,

I., D. Andriashek, and W. Calvert. 1993. Habitat

preferences of polar bears in the western Canadian

Arctic in late winter and spring. Polar Record 29:13-24.

Stirling,

I., C. Spencer, and D. Andriashek. 1989. Immobilization

of polar bears Ursus maritimus with Telazol in the

Canadian Arctic. J. Wildl. Diseases. 25:159-168.

Struzik,

E. 1987. Nanook: in the tracks of the great wanderer.

Equinox Jan.-Feb. 1987. pp. 18-32.

Urquhart,

D. R., and R. E. Schweinsburg. 1984. Polar bear: life

history and known distribution of the polar bear in the

Northwest Territories up to 1981. Northwest Territ.,

Dep. Renew. Resour., Yellowknife. 69 pp.

Uspenskii,

S. M. 1977. The polar bear. Nauka, Moscow, 107 pp.

(English trans. by Canadian Wildl. Serv., 1978).

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

01/23/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|