|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: Mountain Lions |

|

|

Fig. 1. Mountain lion,

Felis concolor

Identification Identification

The mountain lion (cougar, puma, catamount, panther;

Fig. 1) is the largest cat native to North America. The

head is relatively small, and the face is short and

rounded. The neck and body are elongate and narrow. The

legs are very muscular and the hind legs are

considerably longer than the forelegs. The tail is long,

cylindrical, and well-haired. The pelage of the mountain

lion varies considerably. There are two major color

phases — red and gray. The red phase varies from buff,

cinnamon, and tawny to a very reddish color, while the

gray phase varies from silvery gray to bluish and slate

gray. The sides of the muzzle are black. The upper lip,

chin, and throat are whitish. The tail is the same color

as the body, except for the tip, which is dark brown or

black. The young are yellowish brown with irregular rows

of black spots. Male mountain lions are usually

considerably larger than females. Adults range from 72

to 90 inches (183 to 229 cm) in total length including

the tail, which is 30 to 36 inches (76 to 91 cm) long.

They weigh from 80 to 200 pounds (36 to 91 kg). The

mountain lion’s skull has 30 teeth. Female mountain

lions have 8 mammae.

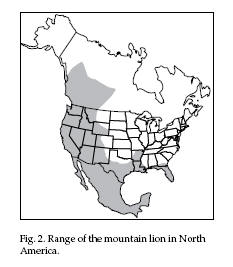

Range

The range of the mountain lion in North America is shown

in figure 2. Its primary range occurs in western Canada

and in the western and southwestern United States.

Sparse populations occur in the south, from Texas to

Florida. Several mountain lion sightings have occurred

in midwestern and eastern states but populations are not

recognized.

Habitat

The mountain lion can be found in a variety of habitats

including coniferous forests, wooded swamps, tropical

forests, open grasslands, chaparral, brushlands, and

desert edges. They apparently prefer rough, rocky,

semiopen areas, but show no particular preferences for

vegetation types. In general, mountain lion habitat

corresponds with situations where deer occur in large,

rugged, and remote areas.

Food

Habits

Mountain lions are carnivorous. Their diet varies

according to habitat, season, and geographical region.

Although deer are their preferred prey and are a primary

component of their diet, other prey will be taken when

deer are unavailable. Other prey range from mice to

moose, including rabbits, hares, beaver, porcupines,

skunks, martens, coyotes, peccaries, bear cubs,

pronghorn, Rocky Mountain goats, mountain sheep, elk,

grouse, wild turkeys, fish, occasionally domestic

livestock and pets, and even insects. Mountain lions,

like bobcats and lynx, are sometimes cannibalistic.

General

Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Mountain lions are

shy, elusive, and primarily nocturnal animals that

occasionally are active during daylight hours. For this

reason they are seldom observed, which leads the general

public to believe that they are relatively rare, even in

areas where lion populations are high. They attain great

running speeds for short distances and are agile tree

climbers. Generally solitary, they defend territories.

Dominant males commonly kill other males, females, and

cubs. A mountain lion’s home range is usually 12 to 22

square miles (31 to 57 k2), although it may travel 75 to

100 miles (120 to 161 km) from its place of birth.

The

mountain lion does not have a definite breeding season,

and mating may take place at any time. In North America

there are records of births in every month, although the

majority of births occur in late winter and early

spring. The female is in estrus for approximately 9

days. After a gestation period of 90 to 96 days, 1 to 5

young (usually 3 or 4) are born. The kittens can eat

meat at 6 weeks although they usually nurse until about

3 months of age. The young usually hunt with their

mother through their first winter.

Historically,

the North American mountain lion population was

drastically reduced by the encroachment of civilization

and habitat destruction. Some populations in the West

are growing rapidly. Local populations may fluctuate in

response to changes in prey populations, particularly

deer, their primary food source.

The

mountain lion is usually hunted as a trophy animal with

the aid of trail and sight hounds. Pelts are used for

trophy mounts and rugs; claws and teeth are used for

jewelry and novelty ornaments. The mountain lion is not

an important species in the fur trade. In North America,

it is primarily harvested in Arizona, New Mexico, Utah,

Colorado, Idaho, western Montana, British Columbia, and

Alberta.

Damage

and Damage Identification

Mountain lions are predators

on sheep, goats, cattle, and horses. House cats, dogs,

pigs, and poultry are also prey. Damage is often random

and unpredictable, but when it occurs, it can consist of

large numbers of livestock killed in short periods of

time. Cattle, horse, and burro losses are often chronic

in areas of high lion populations. Lions are considered

to have negative impacts on several bighorn sheep herds

in New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and Colorado.

In

areas of low deer numbers, mountain lions may kill deer

faster than deer can reproduce, thus inhibiting deer

population growth. This usually occurs only in

situations where alternative prey keep lions in the area

and higher deer populations are not close by.

Lions

are opportunistic feeders on larger prey, including

adult elk and cattle. Individual lions may remain with a

herd and prey on it consistently for many weeks, causing

significant number reductions. Mountain lions cause

about 20% of the total livestock predation losses in

western states annually. Historically, lion damage was

suffered by relatively few livestock producers who

operate in areas of excellent lion habitat and high lion

populations. This historic pattern has changed in recent

years, as lion distribution has spread, resulting in

frequent sightings and occasional damage in residential

developments adjacent to rangelands, montane forests,

and other mountain lion habitat. Predation typically is

difficult to manage although removal of the offending

animals is possible if fresh kills can be located.

Sheep,

goats, calves, and deer are typically killed by a bite

to the top of the neck or head. Broken necks are common.

Occasionally, mountain lions will bite the throat and

leave marks similar to those of coyotes. The upper

canine teeth of a mountain lion, however, are farther

apart and considerably larger than a coyote’s (1 1/2

to 2 1/4 inches [3.8 to 5.7 cm] versus 1 1/8 to 1 3/8

inches [2.8 to 3.5 cm]). Claw marks are often evident on

the carcass. Mountain lions tend to cover their kills

with soil, leaves, grass, and other debris. Long scratch

marks (more than 3 feet [1 m]) often emanate from a kill

site. Occasionally, mountain lions drag their prey to

cover before feeding, leaving well-defined drag marks.

Tracks

of the mountain lion are generally hard to observe

except in snow or on sandy ground. The tracks are

relatively round, and are about 4 inches (10 cm) across.

The three-lobed heel pad is very distinctive and

separates the track from large dog or coyote tracks.

Claw marks will seldom show in the lion track. Heel pad

width ranges from 2 to 3 inches (5 to 8 cm). The tracks

of the front foot are slightly larger than those of the

hind foot. The four toes are somewhat teardrop shaped

and the rear pad has three lobes on the posterior end.

Although

uncommon, mountain lion attacks on humans occasionally

occur. Fifty-three unprovoked mountain attacks on humans

were documented in the US and Canada from 1890 to 1990.

Nine attacks resulted in 10 human deaths. Most victims

(64%) were children who were either alone or in groups

of other children. Attacks on humans have increased

markedly in the last two decades (see Beier 1991).

Legal

Status

All of the western states except California allow

the harvest of lions. They are protected in all other

states where present. Generally, western states manage

mountain lions very conservatively as big game animals.

Lion harvests are severely restricted by the harvest

methods allowed and by quotas.

If

mountain lion predation is suspected in states where

lions are protected, contact a local wildlife management

office for assistance. Most states allow for the

protection of livestock from predators by landowners or

their agents when damage occurs or is expected. Some

states, however, require that a special permit for the

control of mountain lions be obtained or that the

wildlife agency personnel or their agent do the control

work. Several states have a damage claim system that

allows for recovery of the value of livestock lost to

mountain lion predation.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Heavy

woven-wire fencing at least 10 feet (3 m) high is

required to discourage lions. Overhead fencing is also

necessary for permanent and predictable protection.

Fencing is practical only for high-value livestock and

poultry. Night fencing under lights or in sealed

buildings is useful where practical.

Electric

fencing with alternating hot and ground wires can

effectively exclude mountain lions. Wires should be 10

feet (3 m) high, spaced 4 inches (10 cm) apart, and

charged with at least 5,000 volts.

Cultural

Methods Mountain lions prefer to hunt and stay where

escape cover is close by. Removal of brush and trees

within 1/4 mile (0.4 km) of buildings and livestock

concentrations may result in reduced predation.

Chronic

mountain lion predation has led to some ranchers

shifting from sheep to cattle production. In areas with

high levels of predation, some ranchers have changed

from cow-calf to steer operations.

Frightening

Bright lights, flashing white lights, blaring music,

barking dogs, and changes in the placement of scarecrow

objects in livestock depredation areas may temporarily

repel mountain lions. The Electronic Guard, a strobe

light/ siren device developed by USDA-APHIS-ADC, may

also deter lions.

Repellents

No chemical repellents are registered for mountain

lions.

Toxicants

No chemical toxicants are registered for mountain lion

control. Since lions prefer to eat their own kills and

fresh untainted meats, an efficient delivery system for

toxicants has not been developed.

Fig.

3. Bedded trap

Fumigants

No chemical fumigants are registered for use on lions. Fumigants

No chemical fumigants are registered for use on lions.

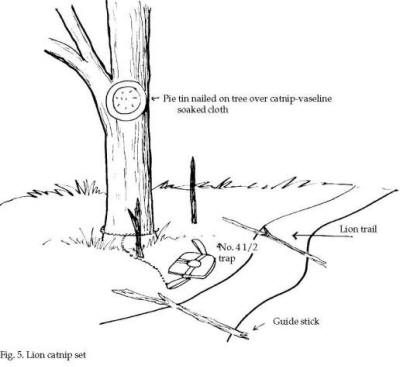

Trapping

Leghold Traps. Mountain lions are extremely strong and

require very strong traps. Well-bedded Newhouse traps in

size No. 4 or 4 1/2 are recommended (Fig 3). Recommended

sets are shown in figures 3 and 4. Use large heavy

drags, sturdy stakes, or substantial trees, posts, or

rocks to anchor traps to ensure against escape.

Mountain

lions are easily trapped along habitual travel ways, in

areas of depredations, and at kill sites. Although blind

sets are usually made in narrow paths frequented by

lions, baits made of fish products, poultry, porcupine,

rabbits, or deer parts, as well as curiosity lures like

catnip, oil of rhodium, and house cat urine and gland

materials are effective attractants. Mountain lions are

very curious and respond to hanging and moving flags of

skin, feathers, or bright objects.

Leg

Snares. Leg snares are effective when set as described

in the Black Bears chapter, and as shown here in figures

4, 5, and 6. Substitute leg snares for the No. 4 or 4

1/2 leghold traps. The Aldrich-type foot snare can be

used to catch mountain lions. This set is made on trails

frequented by lions; stones or sticks are used to direct

foot placement over the triggering device.

Snares.

Snares can be set to kill mountain lions or hold them

alive for tranquilization. Commercially made mountain

lion snares are available from Gregerson Manufacturing

(see Supplies and Materials). They should be suspended

in lion runways and trails (Fig. 7), or set with baits

in cubby arrangements (Figs. 8 and 9).

Kill

snares should be placed with the bottom of the loop

approximately 16 inches (40 cm) above the ground with a

loop diameter of 12 to 16 inches (30 to 41 cm). Snares

intended to capture lions alive should be placed with

the bottom of the loop 14 inches (36 cm) from the ground

and a loop diameter of 18 to 20 inches (46 to 51 cm).

Snares set for live capture should be checked daily from

a distance.

Cage

Traps. Large, portable cage traps are used by

USDA-APHIS-ADC personnel in California to capture

moutain lions that kill pets and livestock in suburban

areas and on small rural holdings. The traps are

constructed of 4-foot (120-cm) wide, 4-foot (120-cm)

high, 10-foot (3-m) long welded-wire stock panels with 2

x 4-inch (5 x 10-cm) grid. The trap is placed where the

mountain lion left the kill, and it is baited with the

remains of the kill. See Shuler (1992) for details on

this method.

Shooting

Mountain lions sometimes return to a fresh kill to feed

and can be shot from ambush when they do so. Locate an

ambush site where the shooter cannot be seen and the

wind carries the shooter’s odor away from the

direction that the cat will use to approach the kill

site. Set up at least 50 yards (45 m) from the kill

site. Calibers from .222 Remington and larger are

recommended. Mountain lions can be called into shooting

range with predator calls, particularly sounds that

simulate the distress cry of a doe deer. See Blair

(1981) for additional information on calling lions.

Other

Methods Trained dogs can be used to capture or kill

depredating lions. The dogs are most often released at

the kill site, where they pick up the lion’s scent and

track the lion until it is cornered or climbs a tree.

The lion can then be shot and removed, or tranquilized

and transplanted at least 300 miles (480 km) away.

Transplanting of lions is not recommended unless they

are moved to an area where no present lion population

exists, where habitat and weather are similar to those

of the original area, and where there will be no problem

of potential depredation by the translocated lions.

Placing a mountain lion in an area with which it is

unfamiliar reduces its chance of survival and is likely

to disrupt the social hierarchy that exists there. Lions

from a distant area may transmit a disease or

contaminate a gene pool that has been maintained through

a natural selection process for population survival in a

specific area. In addition, depredating lions are likely

to cause depredation problems in the area to which they

are transplanted.

Hunting

of mountain lions as big game animals should be

encouraged in areas of predation to lower the

competition for native food sources. To reduce or

eliminate future losses, quick action should be taken as

soon as predation is discovered. Hunting

of mountain lions as big game animals should be

encouraged in areas of predation to lower the

competition for native food sources. To reduce or

eliminate future losses, quick action should be taken as

soon as predation is discovered.

Economics

of Damage and Control Verifying livestock losses to

mountain lions is difficult because of the rough

mountainous terrain and vegetation cover present where

most lion predation occurs. Many losses occur that are

never confirmed. Generally, lion predation is

responsible for only a small fraction of total predation

losses suffered by ranchers, but individual ranchers may

suffer serious losses.

In

Nevada, it was estimated that annual losses of range

sheep to mountain lions averaged only 0.29% (Shuminski

1982). These losses, however, were not evenly

distributed among ranchers. Fifty-nine sheep (mostly

lambs) were killed in one incidence. The mountain lion

involved apparently killed 112 sheep in the area before

it was captured.

In

states such as Colorado and Wyoming, where damages are

paid for lion predation, contact the state wildlife

agency for information about the claims process and

paperwork. Most systems require immediate reporting and

verification of losses before payments are made.

Acknowledgments

Much of this information was prepared by M. L. Boddicker

in “Mountain Lions,” Prevention and Control of

Wildlife Damage (1983).

I

thank Keith Gregerson for use of the snare suspension

and anchoring diagram and the Colorado Trapper’s

Association for use of diagrams of lion sets from its

book (Boddicker 1980). Sections on identification,

habitat, food habits, and general biology are adapted

from Deems and Pursley (1983).

Figures

1 and 2 from Schwartz and Schwartz (1981), adapted by

Jill Sack Johnson.

Figures

3, 4, 5, and 6 from Boddicker (1980).

Figure

7 courtesy of Gregerson Manufacturing Co., adapted by

Jill Sack Johnson.

Figures

8 and 9 by Boddicker, adapted by Jill Sack Johnson.

For

Additional Information

Beier, P. 1991. Cougar attacks on

humans in the United States and Canada. Wildl. Soc.

Bull. 19:403-412.

Blair,

G. 1981. Predator caller’s companion. Winchester

Press, Tulsa, Oklahoma. 267 pp.

Boddicker,

M. L., ed. 1980. Managing rocky mountain furbearers.

Colorado Trappers Assoc., LaPorte, Colorado. 176 pp.

Bowns,

J. E. 1985. Predation-depredation. Pages 204-205 in J.

Roberson and F. G. Lindzey, eds. Proc. Mountain Lion

Workshop, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Deems,

E. F. and D. Pursley, eds. 1983. North American

furbearers: a contemporary reference. Int. Assoc. Fish

Wildl. Agencies and the Maryland Dep. Nat. Resour.,

Annapolis. 223 pp.

Hornocker,

M. G. 1970. An analysis of mountain lion predation upon

mule deer and elk in the Idaho primitive area. Wildl.

Monogr. 21. 39 pp.

Hornocker,

M. G. 1976. Biology and life history. Pages 38-91 in G.

C. Christensen and R. J. Fischer, eds. Trans. mountain

lion workshop, Sparks, Nevada.

Lindzey,

F. G. 1987. Mountain lion. Pages 657668 in M. Novak, J.

A. Baker, M. E. Obbard, and B. Malloch. Wild furbearer

management and conservation in North America. Minist.

Nat. Resour., Toronto, Ontario.

Paradiso,

J. L. 1972. Status report on cats (Felidae) of the

world, 1971. US Fish Wildl. Serv., Special Sci. Rep.,

Wildl. No. 157. 43 pp.

Robinette,

W. L., J. S. Gashwiler, and O. W. Morris. 1959. Food

habits of the cougar in Utah and Nevada. J. Wildl.

Manage. 23:261-273.

Schwartz,

C. W. and E. R. Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of

Missouri. rev. ed. Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356

pp.

Sealander,

J. A., and P. S. Gipson. 1973. Status of the mountain

lion in Arkansas, Proc. Arkansas Acad. Sci. 27:38-41.

Sealander,

J. A., M. G. Hornocker, W. V. Wiles, and J. P. Messick.

1973. Mountain lion social organization in the Idaho

primitive area. Wildl. Mono. 35:1-60.

Shaw,

H. 1976. Depredation. Pages 145-176 in G. C. Christensen

and R. J. Fischer, eds. Trans. mountain lion workshop,

Sparks, Nevada.

Shuler,

J. D. 1992. A cage trap for live-trapping mountain

lions. Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 15:368-370.

Shuminski,

H. R. 1982. Mountain lion predation on domestic

livestock in Nevada. Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 10:62-66.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom; Robert M. Timm; Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION

AND CONTROL OF WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative

Extension Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural

Resources University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United

States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health

Inspection Service Animal Damage Control

Great

Plains Agricultural Council Wildlife Committee

01/23/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|