|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: Mink |

|

|

Identification

The mink (Mustela vison,

Fig. 1) is a member of the weasel family. It is about 18

to 24 inches (46 to 61 cm) in length, including the

somewhat bushy 5- to 7-inch (13- to 18-cm) tail, and

weighs 1 1/2 to 3 pounds (0.7 to 1.4 kg). Females are

about three-fourths the size of males. Both sexes are a

rich chocolate-brown color, usually with a white patch

on the chest or chin and scattered white patches on the

belly. The fur is relatively short with the coat

consisting of a soft, dense underfur concealed by

glossy, lustrous guard hairs. Mink also have anal musk

glands common to the weasel family and can discharge a

disagreeable musk if frightened or disturbed. Unlike

skunks, however, they cannot forcibly spray musk.

Range and Habitat

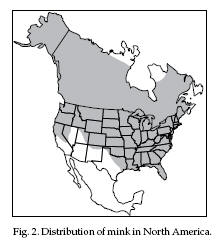

Mink are found throughout

North America, with the exception of the desert

southwest and tundra areas (Fig. 2).

Mink are shoreline

dwellers and their one basic habitat requirement is a

suitable permanent water area. This may be a stream,

river, pond, marsh, swamp, or lake. Waters with good

populations of fish, frogs, and aquatic invertebrates

and with brushy or grassy ungrazed shorelines provide

the best mink habitat. Mink use many den sites in the

course of their travels and the availability of adequate

den sites is a very important habitat consideration.

These may be muskrat houses, bank burrows, holes,

crevices, log jams, or abandoned beaver lodges.

Food Habits

The mink is strictly

carnivorous. Because of its semiaquatic habits, it

obtains about as much food on land as in water. Mink are

opportunistic feeders with a diet that includes mice and

rats, frogs, fish, rabbits, crayfish, muskrats, insects,

birds, and eggs.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Mink are polygamous and

males may fight ferociously for mates during the

breeding season, which occurs from late January to late

March. Gestation varies from 40 to 75 days with an

average of 51 days. Like most other members of the

weasel family, mink exhibit delayed implantation; the

embryos do not implant and begin completing their

development until approximately 30 days before birth.

The single annual litter of about 3 to 6 young is born

in late April or early May and their eyes open at about

3 weeks of age. The young are born in a den which may be

a bank burrow, a muskrat house, a hole under a log, or a

rock crevice. The mink family stays together until late

summer when the young disperse. Mink become sexually

mature at about 10 months of age.

Fig. 2. Distribution of mink in North America.

Mink are active mainly at

night and are active year-round, except for brief

intervals during periods of low temperature or heavy

snow. Then they may hole up in a den for a day or more.

Male mink have large home ranges and travel widely,

sometimes covering many miles (km) of shoreline. Females

have smaller ranges and tend to be relatively sedentary

during the breeding season.

Damage and Damage Identification

Mink may occasionally kill

domestic poultry around farms. They typically kill their

prey by biting them through the skull or neck. Closely

spaced pairs of canine tooth marks are sign of a mink

kill.

Mink will attack animals

up to the size of a chicken, duck, rabbit, or muskrat.

While eating muskrats, a mink will often make an opening

in the back or side of the neck and skin the animal by

pulling the head and body through the hole as it feeds.

Like some other members of the weasel family, mink

occasionally exhibit “surplus killing” behavior (killing

much more than they can possibly eat) when presented

with an abundance of food, such as in a poultry house

full of chickens. Mink may place many dead chickens

neatly in a pile. Mink can eat significant numbers of

upland nesting waterfowl or game bird young,

particularly in areas where nesting habitat is limited.

Legal Status

Mink are protected

furbearers in most states, with seasons established for

taking them when their fur is prime. Most states,

however, have provisions for landowners to control

furbearers which are damaging their property at anytime

of the year. Check with your state wildlife agency

before using any lethal controls.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Mink damage usually is

localized. If needed, lethal controls can be directed at

the individual mink causing the damage.

Exclusion

Usually the best solution

to mink predation on domestic animals is to physically

exclude their entry, sealing all openings larger than 1

inch (2.5 cm) with wood or tin and by using 1-inch

(2.5-cm) mesh poultry netting around chicken yards and

over ventilation openings. Mink do not gnaw like

rodents, but they are able to use burrows or gnawed

openings made by rats.

Habitat

Modification Habitat

modification generally is not a feasible means of

reducing mink predation problems on farms. If the

objective is to increase natural production of upland

nesting wild birds, however, habitat modification may be

applicable. The best method of increasing upland nesting

success is usually to increase the size and quality of

cover areas such as grasslands, legumes, or set-aside

areas. Although increasing the density of nesting cover

may reduce nest predation by mink, it could lead to an

increase in nest predation by species which favor dense

cover, such as the Franklin ground squirrel. Because

mink frequently use multiple den sites, elimination of

potential denning areas may reduce their densities.

Frightening

There are no known

frightening devices that are effective for deterring

mink predation.

Repellents, Toxicants,

and Fumigants

There are no repellents,

toxicants, or fumigants registered for mink damage

control.

Trapping Trapping

Mink can most easily be

captured in leghold traps (No. 11 double long-spring or

No. 1 1/2 coilspring) or in Conibear®-type body-gripping

traps equivalent to No. 120 traps. Mink are suspicious

of new objects and are difficult to capture in live

traps. Single-door live traps may be effective if baited

and placed in dirt banks or rock walls. Double-door live

traps can be effective in runways, particularly if the

trap doors are wired open and the trap is left in place

for some time before activating the trap. Live traps may

also be effective around farmyards because mink are more

accustomed to encountering human-made objects in those

areas.

“Blind sets” are very

effective for mink if suitable locations can be found.

These sets do not require bait or lures and are placed

in areas along mink travel lanes where the animals are

forced to travel in restricted areas (Fig. 3). Good

sites for blind sets include small culverts, tiles,

narrow springs, muskrat runs, and areas under

overhanging banks or under the roots of streamside trees

(Fig. 4). If necessary, the opening can be restricted

with the use of a few sticks or grass to direct the mink

over the trap.

Another good mink set is

the “pocket set” using bait (Fig. 5). This set is made

by digging a 3-inch (7.6-cm) diameter hole horizontally

back into a bank at the water level. The bottom of the

hole should contain about 2 inches (5 cm) of water, and

it should extend back at least 10 inches (25 cm) into

the bank. Place a bait (fresh fish, muskrat carcass, or

frog) in the back of the hole above water level and

place the trap underwater at the opening of the hole.

Traps should be solidly staked and connected to a

drowning wire leading to deep water.

Fig. 3. An obstruction set

catches a mink where it is traveling along the bank and

is forced into the water. Disturbance at the trap site

should be kept to a minimum.

Fig. 4. The spring set

catches the mink where a small feeder stream or tile

outlet enters a larger stream or impoundment.

Fig. 5. The pocket set is

effective for mink. Bait or lure is placed in the back

of the hole above the water level. (Note: the stake is

set off to one side and its top should be driven below

the water line).

Use live traps around a

farmyard if there is a high likelihood of catching pets.

Otherwise, leghold or Conibear® traps can be used with

or without bait in runs or holes used by mink.

Shooting

Some states may have

restrictions on shooting mink, although many will make

exceptions in damage situations. If a mink is raiding

poultry and can be caught in the act, shooting the

animal is a quick way to solve the problem. Normally,

though, it is difficult to shoot mink because of their

nocturnal habits.

Economics of Damage and Control

Although an individual

incident of mink predation can be costly, overall the

problem is not very significant to agriculture. Mink

damage control on a case-by-case basis generally can be

justified from a cost/benefit standpoint, but

large-scale control programs are neither necessary nor

desirable. Exclusion procedures may or may not be

economically justifiable, depending on the severity of

the problem and the amount of repairs needed. Normally,

such costs can be justified for a recurring problem when

amortized over the life of the exclusion structures.

Usually damage from other predators and rodents is

reduced as well.

Mink are important

semiaquatic carnivores in wetland wildlife communities,

and are also valuable as a fur resource. About 400,000

to 700,000 wild mink are harvested each year throughout

North America, for an annual income exceeding $5

million. Therefore, all lethal control should be limited

to specific instances of documented damage.

Acknowledgments

Information for this

section came from a variety of published and unpublished

sources. Information on damage identification was

adapted from Dolbeer et al. (1994).

Figures 1 and 2 from

Schwartz and Schwartz (1981).

Figures 3, 4, and 5 by

Michael D. Stickney, from the New York Department of

Environmental Conservation publication, Trapping

Furbearers, Student Manual (1980), by R. Howard, L.

Berchielli, C. Parsons, and M. Brown. The figures are

copyrighted and are used with permission.

For Additional Information

Dolbeer, R. A., N. R. Holler, and D. W. Hawthorne. 1994.

Identification and control of wildlife damage. Pages

474-506 in T. A. Bookhout, ed. Research and management

techniques for wildlife and habitats. The Wildl. Soc.,

Bethesda, Maryland.

Eagle, T. C., and J. S.

Whitman. 1987. Mink. Pages 614-625 in M. Novak, J. A.

Baker, M. E. Obbard, and B. Mallock, eds. Wild furbearer

management and conservation in North America. Ontario

Trappers Assoc. and Ontario Ministry Nat. Resour.

Linscombe, C., N. Kinler,

and R. J. Aukrich. 1982. Mink. Pages 629-643 in J. A.

Chapman and G. A. Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North

America: biology, management, and economics. The Johns

Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri. rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|