|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: House Cats (Feral) |

|

|

Fig. 1. House cat, Felis

domesticus

Identification

The cat has been the most

resistant to change of all the animals that humans have

domesticated. All members of the cat family, wild or

domesticated, have a broad, stubby skull, similar facial

characteristics, lithe, stealthy movements, retractable

claws (except the cheetah), and nocturnal habits.

Feral cats (Fig. 1) are

house cats living in the wild. They are small in

stature, weighing from 3 to 8 pounds (1.4 to 3.6 kg),

standing 8 to 12 inches (20 to 30.5 cm) high at the

shoulder, and 14 to 24 inches (35.5 to 61 cm) long. The

tail adds another 8 to 12 inches (20 to 30.5 cm) to

their length. Colors range from black to white to

orange, and an amazing variety of combinations in

between. Other hair characteristics also vary greatly.

Range

Cats are found in

commensal relationships wherever people are found. In

some urban and suburban areas, cat populations equal

human populations. In many suburban and eastern rural

areas, feral house cats are the most abundant predators.

Habitat

Feral cats prefer areas in

and around human habitation. They use abandoned

buildings, barns, haystacks, post piles, junked cars,

brush piles, weedy areas, culverts, and other places

that provide cover and protection.

Food Habits

Feral cats are

opportunistic predators and scavengers that feed on

rodents, rabbits, shrews, moles, birds, insects,

reptiles, amphibians, fish, carrion, garbage,

vegetation, and leftover pet food.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Feral cats produce 2 to 10

kittens during any month of the year. An adult female

may produce 3 litters per year where food and habitat

are sufficient. Cats may be active during the day but

typically are more active during twilight or night.

House cats live up to 27 years. Feral cats, however,

probably average only 3 to 5 years. They are territorial

and move within a home range of roughly 1.5 square miles

(4 km2). After several generations, feral cats can be

considered to be totally wild in habits and temperament.

Damage Feral cats feed

extensively on songbirds, game birds, mice and other

rodents, rabbits, and other wildlife. In doing so, they

lower the carrying capacity of an area for native

predators such as foxes, raccoons, coyotes, bobcats,

weasels, and other animals that compete for the same

food base.

Where documented, their

impact on wildlife populations in suburban and rural

areas—directly by predation and indirectly by

competition for food— appears enormous. A study under

way at the University of Wisconsin (Coleman and Temple

1989) may provide some indication of the extent of their

impact in the United States as compared to that in the

United Kingdom, where Britain’s five million house cats

may take an annual toll of some 70 million animals and

birds (Churcher and Lawton 1987). Feral cats

occasionally kill poultry and injure house cats.

Feral cats serve as a

reservoir for human and wildlife diseases, including cat

scratch fever, distemper, histoplasmosis, leptospirosis,

mumps, plague, rabies, ringworm, salmonellosis,

toxoplasmosis, tularemia, and various endo- and

ectoparasites.

Legal Status

Cats are considered

personal property if ownership can be established

through collars, registration tags, tattoos, brands, or

legal description and proof of ownership. Cats without

identification are considered feral and are rarely

protected under state law. They become the property of

the landowner upon whose land they exist. Municipal and

county animal control agencies, humane animal shelters,

and various other public and private “pet” management

agencies exist because of feral or unwanted house cats

and dogs. These agencies destroy millions of stray cats

annually.

State, county, and

municipal laws related to cats vary. Before lethal

control is undertaken, consult local laws. If live

capture is desired, consult the local animal control

agency for instructions on disposal of cats.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods Exclusion

Exclusion by

fencing, repairing windows, doors, and plugging holes in

buildings is often a practical way of eliminating cat

predation and nuisance. Provide overhead fencing to keep

cats out of bird or poultry pens. Wire mesh with

openings smaller than 2.5 inches (6.4 cm) should offer

adequate protection.

Cultural Methods

Cat numbers can be reduced

by eliminating their habitat. Old buildings should be

sealed and holes under foundations plugged. Remove brush

and piles of debris, bale piles, old machinery, and

junked cars. Mow vegetation in the vicinity of

buildings. Elimination of small rodents and other

foodstuffs will reduce feral cat numbers.

Repellents

The Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA) has registered the following

chemicals individually and in combination for repelling

house cats: anise oil, methyl nonyl ketone, Ro-pel, and

Thymol. There is little objective evidence, however, of

these chemicals’ effectiveness. Some labels carry the

instructions that when used indoors, “disciplinary

action” must reinforce the repellent effect. Some

repellents carry warnings about fabric damage and

possible phytotoxicity. When used outdoors, repellents

must be reapplied frequently. Outdoor repellents can be

used around flower boxes, furniture, bushes, trees, and

other areas where cats are not welcomed. Pet stores and

garden supply shops carry, or can order, such

repellents. The repellents are often irritating and

repulsive to humans as well as cats.

Frightening

Dogs that show aggression

to cats provide an effective deterrent when placed in

fenced yards and buildings where cats are not welcome.

Toxicants

No toxicants are

registered for control of feral cats.

Fumigants

No fumigants are

registered for control of feral house cats. Live-trapped

cats or cats in holes or culverts can be euthanized with

carbon dioxide gas or pulverized dry ice (carbon

dioxide) at roughly 1/2 pound per cubic yard (0.3 kg/m3)

of space.

Trapping

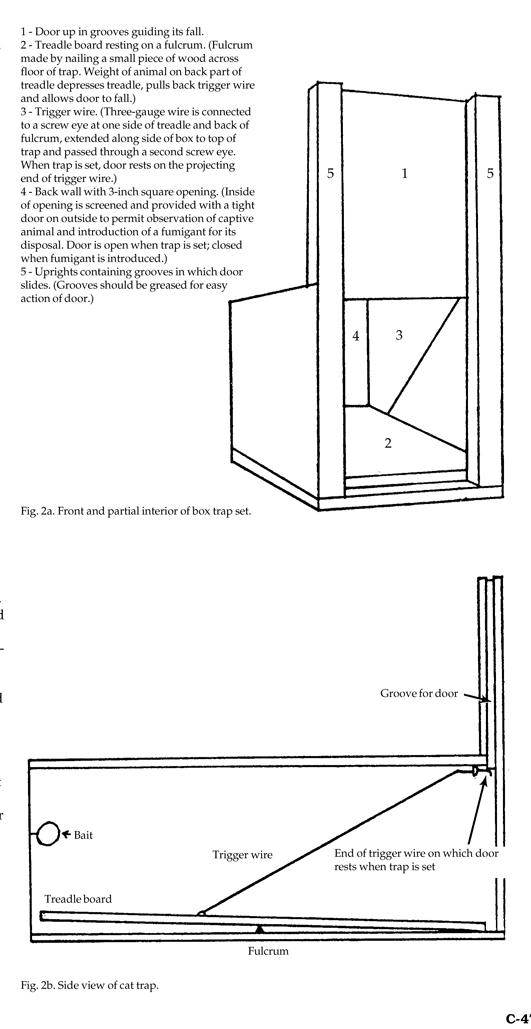

Live

Traps. Live-trapping cats in commercial or

homemade box traps (Fig. 2) is a feasible control

alternative, particularly in areas where uncontrolled

pets are more of a problem than wild cats. Trap openings

should be 11 to 12 inches (28 to 30 cm) square and 30

inches (75 cm) or more long. Double-ended traps should

be at least 42 inches (105 cm) long. The cat can be

captured and turned over to animal control agencies

without harm, given back to the owner with proper

warnings, or euthanized by shooting, lethal injection,

or asphyxiation with carbon dioxide gas. Sources for

commercial traps are found in Supplies and Materials.

Set live traps in areas of feral cat activity, such as

feeding and loafing areas, travelways along fences, tree

lines, or creeks, dumps, and garbage cans. Successful

baits include fresh or canned fish, commercial cat

foods, fresh liver, and chicken or rodent carcasses.

Catnip and rhodium oil are often effective in attracting

cats. Live

Traps. Live-trapping cats in commercial or

homemade box traps (Fig. 2) is a feasible control

alternative, particularly in areas where uncontrolled

pets are more of a problem than wild cats. Trap openings

should be 11 to 12 inches (28 to 30 cm) square and 30

inches (75 cm) or more long. Double-ended traps should

be at least 42 inches (105 cm) long. The cat can be

captured and turned over to animal control agencies

without harm, given back to the owner with proper

warnings, or euthanized by shooting, lethal injection,

or asphyxiation with carbon dioxide gas. Sources for

commercial traps are found in Supplies and Materials.

Set live traps in areas of feral cat activity, such as

feeding and loafing areas, travelways along fences, tree

lines, or creeks, dumps, and garbage cans. Successful

baits include fresh or canned fish, commercial cat

foods, fresh liver, and chicken or rodent carcasses.

Catnip and rhodium oil are often effective in attracting

cats.

Leghold Traps.

Leghold traps No. 1, 1.5, or 2 are sufficient to catch

and hold feral cats (Fig. 3). These traps are

particularly useful on cats that are not susceptible to

box traps. Place the traps in a shallow hole the size

and shape of the set trap. Cover the pan with waxed

paper and then cover the trap with sifted soil, sawdust,

or potting soil. Place the bait material far enough

beyond the trap that the cat must step on the trap to

reach it. Traps can be set at entrances to holes where

cats are hiding, entryways to buildings, or near garbage

cans. Domestic cats caught in leghold traps should be

handled with care. Cover the cat with a blanket, sack,

or coat; pin it down with body weight; and release the

trap. Catch poles can also be used to subdue trapped

cats.

Conibear® or Body-gripping

Traps. Conibear® or body-gripping traps are lethal traps

that work like double-jawed mouse traps. They should be

set only where no other animals will get into them. The

No. 220 size is most effective for cats. Set traps in

front of culverts or entry holes, in garbage cans, or

boxes with the bait placed in the back (Fig. 3).

Snares.

Snare sizes No. 1 and 2 are very effective as live traps

or kill traps when set properly. Place snares in

entrances to dens or crawlthroughs, in trails in weeds,

or in garbage cans, boxes, or other restricted access

arrangements where bait is placed (Fig. 4). Sources for

snares are found in Supplies and Materials.

Shooting

Feral cats can be shot

with .22 rimfire and other calibers of centerfire rifles

and shotguns in rural areas where it is safe. In

buildings and urban areas, powerful air rifles are

capable of killing cats with close-range head shots.

Cats can be lured out of heavy cover for a safe shot by

using predator calls, elevated decoys of fur or

feathers, or meat baits.

Other Methods

Supplemental feeding of

feral or free-roaming house cats will probably have

little effect in reducing their depredations on

songbirds and other wildlife. Even well-fed cats will

often bring home a small prey they have caught and

proudly display it to their owners without eating it.

Laboratory studies suggest that hunger and hunting are

controlled by separate neurological centers in the cat

brain, so the rate of predation is not affected by the

availability of cat food.

The hunter is often the

hunted. Dogs and coyotes, which are adapting to urban

environments, are probably the greatest predators of

cats, next to humans and cars. Feral cats are often

found on the borders of human habitation. Large

predators such as bobcats, mountain lions, fox, coyotes,

and feral dogs eliminate cats that stray too far a field

In the final analysis,

many problems with feral cats could be avoided if cat

owners would practice responsible pet ownership. The

same licensing and leash laws pertaining to dogs should

be applied to cats. Spaying or neutering should be

encouraged for household pets not kept for breeding

purposes. Neutering is not a cost-effective program for

controlling feral populations. Unwanted cats should be

humanely destroyed, not abandoned to fend for

themselves.

Economics of Damage and Control

The place of cats in the

modern urban world is certainly secure even though their

reputation as rodent controllers has not been supported

by objective research. Cats have replaced dogs as the

most common family pet in the United States. Their

owners support a growing segment of the economy in the

pet food and pet supplies industries. On the other hand,

feral cats are responsible for the transmission of many

human and wildlife diseases and kill substantial amounts

of wildlife.

Acknowledgments

I wish to acknowledge M.

L. Boddicker, who was the author of the “House Cats”

chapter in the 1983 edition of Prevention and Control of

Wildlife Damage.

Figure 1 by Emily Oseas

Routman.

Figure 2 adapted from

Boddicker (1978), “Housecats” in F. R. Henderson,

Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage, Kansas State

Univ., Manhattan.

Figure 3 by M. L.

Boddicker, adapted by Jill Sack Johnson.

Figure 4 courtesy of

Gregerson Manufacturing Co., adapted by Jill Sack

Johnson.

For Additional Information

Anonymous. 1974. Ecology of the surplus dog and cat

problem. Proc. Natl. Conf. Am. Humane Assoc., Denver,

Colorado. 128pp.

Bisseru, B. 1967. Diseases

of man acquired from his pets. Wm. Heinermann Medical

Books, London. 482 pp.

Boddicker, M. L. 1979.

Controlling feral and nuisance house cats. Colorado

State Univ. Ext. Serv., S.A. Sheet No. 6.508, Ft.

Collins.

Churcher, P. B., and J. H.

Lawton. 1987. Predation by domestic cats in an English

village. J. Zool. (London) 212:439-455.

Coleman, J. S., and S. A.

Temple. 1989. Effects of free-ranging cats on wildlife:

a progress report. Proc. Eastern Wildl. Damage Control

Conf. 4:9-12.

Coman, B. J., and H.

Brunner. 1972. Food habits of the feral house cat in

Victoria. J. Wildl. Manage. 36:848-853.

Errington, P. L. 1936.

Notes on food habits of southern Wisconsin house cats.

J. Mammal. 17:64-65.

Fitzwater, W. D. 1986.

Extreme care needed when controlling cats. Pest Control

54:10.

Jackson, W. B. 1951. Food

habits of Baltimore, Maryland cats in relation to rat

populations. J. Mammal. 32:458-461.

Parmalee, P. W. 1953. Food

habits of the feral house cat in east-central Texas. J.

Wildl. Manage. 17:375-376.

Remfry, J. 1985. Humane

control of feral cats. Pages 41-49 in D. P. Britt, ed.

Humane control of land mammals/birds. Univ. Fed. An.

Welfare. United Kingdom.

Rolls, E. C. 1969. They

all ran wild: the story of pests on the land in

Australia. Angus and Robertson, Sydney and London.

444pp.

Tuttle, J. L. 1978. Dogs

and cats need responsible owners. Univ. Illinois Coop.

Ext. Serv. Circ. No. 1149.

Warner, R. E. 1985.

Demography and movements of free-ranging domestic cats

in rural Illinois. J. Wildl. Manage. 49:340-346.

Webb, C. H. 1965. Pets,

parasites, and pediatrics. Pediatrics 36:521-522.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

01/23/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|