|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: Grizzly or Brown Bears |

|

|

Introduction

Although wildlife

management concepts were formed nearly 100 years ago,

bears and their management have been poorly understood.

Recent concern for the environment, species

preservation, and ecosystem management are only now

starting to affect the way we manage grizzly/brown bears

( Ursus arctos , Fig. 1). Indeed, the difficulty in

understanding brown bear biology, behavior, and ecology

may have precluded sufficient change to prevent the

ultimate loss of the species south of Canada.

Grizzly/brown bears must be managed at the ecosystem

level. The size of their ranges and their need for safe

corridors between habitat units bring them into

increasing conflict with people, and there seems to be

little guarantee that people will sufficiently limit

their activities and land-use patterns to reduce brown

bear damage rates and the consequent need for damage

control. Drastic changes may be needed in land-use

management, zoning, wilderness designation, timber

harvest, mining, real estate development, and range

management to preserve the species and still meet damage

control needs.

Identification

The brown bears of the

world include numerous subspecies in Asia, Europe, and

North America. Even the polar bear, taxonomically, may

be a white phase of the brown bear. Support for this

concept is provided by new electrophoresic studies and

the fact that offspring of brown/polar bear crosses are

fertile. The interior grizzly ( Ursus arctos horribilis

) is generally smaller than the coastal ( Ursus arctos

gyas ) or island ( Ursus arctos middendorffi )

subspecies of North American brown bear, and it has the

classic “grizzled” hair tips.

Brown bears in general are

very large and heavily built. Male brown bears are

almost twice the weight of females. They walk with a

plantigrade gait (but can walk upright on their hind

legs), and have long claws for digging (black bears and

polar bears have sharper, shorter claws). The males can

weigh up to 2,000 pounds (900 kg), but grizzly males are

normally around 400 to 600 pounds (200 to 300 kg).

Wherever brown bears live, their size is influenced by

their subspecies status, food supply, and length of the

feeding season. Bone growth continues through the sixth

year, so subadult nutrition often dictates their size

potential.

Brown bears are typically

brown in color, but vary from pure white to black, with

coastal brown bears and Kodiak bears generally lighter,

even blond or beige. The interior grizzly bears are

typically a dark, chocolate brown or black, with

pronounced silver tips on the guard hairs. This

coloration often gives them a silvery sheen or halo.

They lack the neck ruff of the coastal bears, and

grizzlies may even have light bands before and behind

the front legs. Some particularly grizzled interior

brown bears have a spectacled facial pattern similar to

that of the panda or spectacled bears of Asia and South

America.

White grizzlies (not

albinos) are also found in portions of Alberta and

Montana, and in south-central British Columbia. Such

white brown bears may be genetically identical to the

polar bear, but so far electrophoresic studies have not

been completed to determine the degree of relatedness.

The interior grizzly’s

“hump,” an adaptation to their digging lifestyle, is

seen less in the coastal brown bears, polar bears, or

black bears. The brown bears (including the grizzly) are

also characterized by their high eye profile,

dish-shaped face, and short, thick ears.

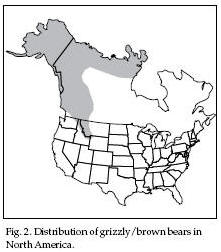

Range Range

The brown bears of North America have lost

considerable range, and are currently restricted to

western Canada, Alaska, and the northwestern United

States (Fig. 2). Their populations are considered secure

in Canada and Alaska, but have declined significantly in

the lower 48 states. Before settlement, 100,000 brown

bears may have ranged south of Canada onto the Great

Plains along stream systems such as the Missouri River,

and in isolated, small mountain ranges such as the Black

Hills of South Dakota. They were scattered rather thinly

in Mexico and in the southwestern United States, but may

have numbered about 10,000 in California, occupying the

broad, rich valleys as well as the mountains.

A few brown bears (the

“Mexican” or “California” grizzly) may still exist in

northern Mexico. Occasionally, barren-ground grizzlies

are found hunting seals on the sea ice north of the

Canadian mainland. The barren-ground grizzlies appear to

be brown bear/ polar bear crosses, and could represent

an intergrade form. Brown bears also occur on three

large islands in the gulf of Alaska, and are isolated

geographically from very similar coastal brown bears.

A nearly isolated

population (the Yellowstone grizzly) occurs in southern

Montana, Wyoming, and southern Idaho. There could still

be a few grizzlies in the mountains of southwestern

Colorado, and a few still range out onto the prairies of

Alberta and Montana, where the extinct Plains grizzly

used to roam.

Habitat

Grizzly/brown bear habitat

is considerably varied. Brown bears may occupy areas of

100 to 150 square miles (140 to 210 km 2 ), including

ID="LinkTarget_1062" desert and prairie as well as

forest and alpine extremes. The areas must provide

enough food during the 5 to 7 months in which they feed

to meet their protein, energy, and other nutritional

requirements for reproduction, breeding, and denning.

They often travel long distances to reach seasonally

abundant food sources such as salmon streams, burned

areas with large berry crops, and lush lowlands.

Denning habitats may be a

limiting factor in brown bear survival. Grizzly bears

seek and use denning areas only at high elevations

(above 6,000 feet [1,800 m]), where there are deep soils

for digging, steep slopes, vegetative cover for roof

support, and isolation from other bears or people. Since

grizzlies select and build their dens in late September,

when their sensitivity to danger is still very high,

even minor disturbances may deter the bears from using

the best sites. Unfortunately, the habitat types bears

choose in September are scarce, and human recreational

use of the same high-elevation areas is increasing.

Travel corridors

connecting large areas of grizzly habitat to individual

home ranges are critical for maintaining grizzly

populations. Adequate cover is also needed to provide

free movement within their range without detection by

humans. The land uses with the greatest impact on bear

habitats and populations include road development,

mining, clear-cut logging, and real estate development.

Coastal brown bears use

totally different habitats than the interior grizzly.

They establish home ranges along coastal plains and

salmon rivers where they feed on grasses, sedges, forbs,

and fish. While the fishing brown bears may use very

small ranges for extended periods, almost all bears make

occasional, long-distance movements to other areas where

food is abundant. This far-ranging behavior often leads

to unexpected human-bear conflicts far from typical

brown bear range.

Social factors within bear

populations influence habitat value—the removal of one

dominant bear or the sudden deaths of several bears can

cause the remaining bears to greatly alter their

habitat-use patterns. Such changes occur simply because

the social hierarchy within bear populations typically

gives large bears dominance over the smaller ones, and

each bear uses its range based on its relationship to

the other bears in the area.

Food Habits

Food gathering is a top

priority in the life of grizzly/brown bears. They feed

extensively on both vegetation and animal matter. Their

claws and front leg muscles are remarkably well adapted

to digging for roots, tubers, and corms. They may also

dig to capture ground squirrels, marmots, and pocket

gophers. Brown bears are strongly attracted to succulent

forbs, sedges, and grasses. In spring and early summer

they may ingest up to 90 pounds (40 kg) of this

high-protein forage per day. Bears gain their fat

reserves to endure the 5- to 7-month denning period by

feeding on high-energy mast (berries, pine nuts) or

salmon. The 2 1/2- to 3-month summer feeding period is

particularly crucial for reaching maximum body frame and

preparing for the breeding season and winter.

Being ultimate

opportunists, brown bears feed on many other food items.

For example, the Yellowstone grizzlies have clearly

become more predatory since the closure of the garbage

dumps in the Yellowstone area. They are exploiting the

abundant elk and bison populations that have built up

within the park. They hunt the elk calves in the spring,

and some bears learn to hunt adult elk, moose, and even

bison. The ungulate herds, domestic sheep, and cows also

provide an abundant carrion supply each spring—the

animals that die over winter thaw out just when the

bears need a rich food source.

Bears are adept at

securing food from human sources such as garbage dumps,

dumpsters, trash cans, restaurants, orchards, and bee

yards. Some bears learn to prey on livestock, especially

sheep that graze on open, remote rangeland.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Brown bears are typical of

all bears physiologically, behaviorally, and

ecologically. They are slow growing and long-lived (20

to 25 years). Their ability to store and use fat for

energy makes long denning periods (5 to 7 months)

possible. During denning they enter a form of

hibernation in which their respiration rate

(approximately 1 per minute) and heart rate (as low as

10 beats per minute) are greatly reduced. Their body

temperature remains just a few degrees below normal;

they do not eat, drink, defecate, or urinate, and their

dormancy is continuous for 3 to 7 months. The adaptive

value of winter denning relates to survival during

inclement weather, when reduced food availability,

decreased mobility, and increased energy demands for

thermoregulation occur.

In most populations, brown

bears breed from mid-May to mid-July. Both males and

females are polygamous, and although males attempt to

defend females against other males, they are generally

unsuccessful. Implantation of the fertilized ova is

delayed until the females enter their dens, from late

October to November. One to three (usually two) cubs are

born in January in a rather undeveloped state. They

require great care from their mothers, which leads to

strong family bonding and transfer of information from

mothers to offspring. Brown bears may not produce young

until 5 to 6 years of age and may skip 3 to 6 years

between litters. Because of their low reproductive

potential, bear populations cannot respond quickly to

expanded habitats or severe population losses.

During the breeding

season, male and female grizzly/brown bears spend

considerable time together, and family groups break up.

The young females are allowed to remain in the area,

taking over a portion of their mother’s range. They are

not threatened by the males, even though they are still

vulnerable without their mother’s protection. The young

males, however, must leave or be killed by the adult

males. Many subadult males disperse into marginal bear

habitats while trying to establish their own

territories. This often leads to increased human-bear

conflicts and the need for management and control

actions.

Home ranges vary in size,

shape, and amount of overlap among individuals.

Abundance and distribution of food is the major factor

determining bear movements and home range size. Home

ranges are smallest in southeastern Alaska and on Kodiak

Island. The largest home ranges are found in the Rocky

Mountains of Canada and Montana, the tundra regions of

Alaska and Canada, and the boreal forest of Alberta. In

areas where food and cover are abundant, brown bear home

ranges can be as small as 9 square miles (24 km 2 ).

Where food resources are scattered, the ranges must be

at least ten times larger to provide an adequate food

base.

Some bears establish

seasonal patterns of movement in relation to dependable

high-calorie foods sources, such as salmon streams and

garbage dumps. Such movements are likely to place bears

in close contact with humans. In addition to finding

food, bears spend considerable time in attempting to

detect people, evaluating situations, and taking

corrective actions to avoid conflict with humans.

People, on the other hand, typically go noisily about

their business, often without ever knowing that a bear

is nearby.

Damage and Damage Identification

Brown bears have many

unique behaviors that subject them to situations in

which they are perceived as a threat to humans or

personal property. They are opportunistic feeders that

may switch to scavenging human-produced food and garbage

if made available, becoming a problem around parks, camp

grounds, cottages, suburban areas, and garbage dumps.

Bears that are conditioned to human foods become used to

the presence of humans and are therefore the most

dangerous. Bear activity is intensely oriented to the

summer months when people are also most active in the

mountains and forests. Brown bear attacks have resulted

in injuries ranging from superficial to debilitating,

disfiguring, and fatal. Dr. Stephen Herrero documented

165 injuries to humans resulting from encounters with

brown bears in North America from 1900 to 1980 (Herrero

1985). Fifty percent of the injuries were classified as

major, requiring hospitalization for more than 24 hours

or resulting in death. In addition to the 19 grizzly

bear-inflicted deaths that Herrero reported, two

Department of Public Safety employees reported 22 deaths

in Alaska.

Brown bears also

occasionally cause problems around orchards, bee yards,

growing crops, and livestock. Some bears occasionally

kill cattle, sheep, pigs, horses, goats, and poultry,

but most do not prey on livestock. Bears kill livestock

by pursuing them at high speed, slashing from the rear

and pulling the prey down. They hold the prey with their

own weight while biting the head or neck area and

delivering blows. The ventral area is then ripped open,

and the hide sometimes skinned, sometimes devoured along

with subcutaneous and visceral fat. Bears eat large

volumes of flesh and body parts, leaving many large

scats. Adult brown bear scats are 2 inches (5 cm) or

more in diameter. The bear will often cover the remains

with all types of nearby debris—vegetation, leaves,

sticks, and soil, and then bed nearby. The investigator

should look carefully for (and record) all wounds,

tracks, hairs, and any other sign that would prove bear

predation. It is important to document accurately the

cause of death, the manner of killing, and all signs in

the area that would indicate predation by bears. The

lack of any such evidence should preclude brown bear

control.

Sheep predation may be

more subtle to document since, when frightened, sheep

readily stampede and injure or kill themselves on felled

timber or cliffs. In such a case, examiners should look

carefully for neck and head bites, or smashed skulls, as

well as tracks, bear hair, bear droppings, and other

sign. Survey the overall scene—the flight path of the

sheep, the place of cover and possible attack relative

to the flight route, the amount consumed, and the

freshness of any flesh or tissues in the bear droppings.

Grizzly/brown bear attacks

are often easily identified by tracks alone. The foot

prints are very large, with claw marks on the front foot

extending up to 4 inches (10 cm) in front of the toe

marks. The toes of a grizzly are in a much straighter

line than those of a black bear, and the grizzly paw

includes greater “webbing” between the toes, which may

show up in a mud print. Grizzly hair found in the area

is another positive identifying characteristic. Look

carefully on the ends of broken sticks, in rough areas

on logs, under high logs, in the bark of trees, or in

any pitch patches on conifers where a bear may have

rubbed. Also check the barbs of any wire fencing nearby.

All hair should be collected carefully in small

envelopes and sent to a wildlife agency or university

lab for identification.

Most bear depredations are

easily identified, especially if there is wet or soft

ground in the area. Bears are not sneaky—they march

right in and take what they consider is theirs.

Legal Status

Grizzly bears south of

Canada are protected as a “threatened species” under the

US Endangered Species Act of 1973. Wyoming and Montana

have limited grizzly bear hunting seasons as authorized

under the act, but the seasons are currently closed

pending clarification of the act through legal

challenges in court and further actions by the states.

Without state hunting seasons, killing of grizzlies is

allowed only through official control actions or defense

of self and property. North of the Canadian border,

grizzlies are hunted to varying extents in Alaska,

ID="LinkTarget_1093" Alberta, British Columbia, the

Yukon, and the Northwest Territories.

Wrongful killing of a

grizzly bear mandates a severe penalty—up to $20,000 in

fines. “Taking” is being more liberally defined as court

challenges establish that even habitat destruction can

be interpreted as taking or killing.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

The challenges of

exclusion are formidable. Bears are incredibly adept at

problem solving where food is concerned, no doubt as a

result of their extreme orientation to food for a few

short months. Brown bears will expend a great amount of

energy and time digging under, breaking down, or

crawling over barriers to food. They know how to use

their great weight and strength to open containers. They

will chew metal cans “like bubble gum” to extract the

food.

To exclude bears, use

heavy, chain-link or woven-wire fencing at least 8 feet

(2.4 m) high and buried 2

feet (0.6 m) below ground. Install metal bar extensions

at an outward angle to the top of the fence and attach

barbed wire or electrified smooth wire. Also consider

attaching an electrified outrigger wire to the fence.

Electric fencing is also

very effective if built correctly. At a minimum,

12gauge, high-tensile fencing should be used—nine wires

high, spaced 6 inches (15 cm) at the top and 4 inches

(10 cm) at the bottom, with alternating hot and ground

wires. Both the top and bottom wires should be hot. Use

a low-impedance charger with a minimum output of 5,000

volts.

In backcountry situations,

an electric fence perimeter may be the only sure

protection from grizzly/brown bear damage. Secure the

camp, supplies, and livestock within the confined area.

In the absence of fencing, bear-proof containers provide

the best protection for food and other supplies. Use

45gallon (200-l) oil drums with locking lids to secure

all bear attractants. Backpackers in bear country should

use portable bear-proof containers. Attractants (food,

meat, feed) can also be hung in an elaborate, bear-proof

manner, at least 20 feet (6.5 m) above ground, and free

from any aerial approach. Tower caches, 20 feet high or

higher, can also be constructed using heavy poles and

timbers.

Cultural Methods

Once a bear has developed

a detrimental behavior, it may be impossible to change

it. Prevention is directed mostly at keeping the bear

population wild and fearful of people. If the mothers

teach their young to avoid humans, problems will be

minimal, though not nonexistent. Hunting pressure

automatically teaches bears to avoid humans.

Choose campsites, bee

yards, and livestock bedding sites in areas not

frequented by bears. Avoid riparian areas, rough ground,

heavy cover, aspen groves, and berry-covered hillsides.

In spring and early summer, bears frequent riparian

areas, low-elevation flood plains, hillside parks, and

alluvial fans where high protein grasses, sedges, and

forbs are plentiful. In late June or early July, bears

turn to areas with berries and other high-energy foods.

Often, livestock need to be held out of such areas only

an extra 2 weeks, until the bears turn to other foods.

In areas with a history of bear problems, livestock

should be confined in buildings or pens that are at

least 50 yards (50 m) from wooded areas and protective

cover, especially during the lambing or calving season.

Remove carcasses from the site and dispose of them by

rendering or deep burial.

Bears should never be fed

or intentionally given access to food scraps or garbage.

Eliminate all sources of human foods around campsites,

cabins, restaurants, and suburban areas. Keep garbage in

clean and tightly sealed metal or plastic containers.

Spray garbage cans and dumpsters regularly with

disinfectants to reduce odors. Maintain regular garbage

pickup schedules and bury or burn all garbage at fenced

sanitary landfills.

Frightening Devices

Boat horns, cracker

shells, rifle shots, and other loud noises may frighten

bears from an area. Roaring engines and helicopter

chases may also be effective. Barking dogs can be very

useful, but they must be trained to bark on sight or

smell of a bear. In addition, good bear dogs will chase

bears, but they must be trained to pursue and corner

without closing on the bear.

Lights and strobe flashes

are only marginally effective for bear damage

prevention.

Repellents and Deterrents

Capsaicin spray has been

reported to be an effective repellent. It may work only

once, however, so a backup deterrent should always be

available.

Well-trained dogs can

provide an “early warning system” as well as a

deterrence to bears. Unfortunately, not many trained

dogs are available in the United States or Canada.

Plastic slugs may also be an effective deterrent against

bears. Bears usually move rapidly to the nearest cover

when frightened, so care must be taken to avoid being

positioned between the bear and escape cover.

Trapping

The capture and

translocation of bears can be effective in damage

control. Unfortunately, relocation often only moves the

problem to another site, and bears have been known to

travel great distances to return to a trapping site. The

handling process, if done correctly, is itself

sufficiently traumatic to teach the bears to avoid

humans. Use culvert traps or foot snares to capture

bears. Care must be taken in baiting to avoid

conditioning bears to people— use only natural scents

and baits such as wild animal road kills. Only properly

trained personnel should be assigned to such work. The

Ursid Research Center in Missoula, Montana, offers

courses in capturing and handling bears. Consult state

regulations and wildlife agency personnel before

implementing any bear-trapping program.

Immobilizing and Handling

Bears are occasionally

captured by injection with an immobilizing drug

administered from a syringe dart fired from a capture

gun. Bears have been successfully immobilized with darts

fired from close range. Bears can be approached on foot,

from vehicles, and from helicopters. The drugs most

commonly used include a mixture of ketamine

hydrochloride and xylazine hydrochloride (Ketaset-Rompun).

This mixture has a high therapeutic index and results in

little distress to the animal.

The drugs chosen, the

degree of sanitation, the approach to the set, the

weapons carried, and the size of capture crews are

extremely crucial in tending the animal. Interning with

a recognized expert, or attending a certified course

should be required before attempting to capture brown

bears.

Shooting

Many grizzlies have been

killed in response to livestock depredations, as allowed

under the US Endangered Species Act. Over time, public

tolerance for this approach has declined and fewer bears

are now being killed or removed. Currently, shooting is

used most often on adult males, since they are not

considered essential in a population. This may, however,

be short-sighted, considering that all other bears in an

area modify their own behavior based on the activities

of the dominant adult male bear. Left alone, a bear

often will not kill livestock again, or could be trained

through aversive conditioning not to attack livestock

again.

Firearms should be carried

by people working with bears or in areas where the risk

of bear attack is high. The best protective weapons are

high-powered rifles of .350 caliber or larger and

12gauge pump shotguns with rifled slugs. Handguns (.44

magnum) should be carried for quick defense only.

Aversive Conditioning

Aversive conditioning may

be effective in teaching bears to fear humans. In

Montana, problem bears were captured and brought into

holding facilities where they were repeatedly confronted

by humans and repelled with chemical sprays. Treatment

was complete when the bear fled instantly to the

“sanctuary” portion of an enclosure. The bear was then

quickly returned to the wild. The captive process,

called “bear school,” lasts only 4 to 6 days. This

method can only be conducted by fully trained personnel.

Field treatment may follow, using radio collars, 24-hour

monitoring, and firearm backup. Aversive conditioning

may cost up to $6,000 per animal, but it may be

cost-effective, considering the alternatives.

Public Education

Public attitudes are

crucial in determining what damage prevention or control

is practical. The State of Montana now has two staff

members authorized to work closely with people in

grizzly range not only to solve bear problems but to

meet with the public and listen to their concerns. They

talk in schools and at rural functions and work with

individual ranchers to solve special problems or help in

emergencies.

Avoiding Human-Bear

Conflicts

Preventing Bear Attack.

Grizzly/ brown bears must be respected. They have great

strength and agility, and will defend themselves, their

young, and their territories if they feel threatened.

They are unpredictable and can inflict serious injury.

NEVER feed or approach a bear.

To avoid a bear encounter,

stay alert and think ahead. Always hike in a group.

Carry noisemakers such as bells or cans containing

stones. Most bears will leave a vicinity if they are

aware of a human presence. Remember that noisemakers may

not be effective in dense brush and near rushing water.

Be especially alert when traveling into the wind since

bears may not pick up your scent and may be unaware of

your approach. Stay in the open and avoid food sources

such as berry patches and carcass remains. Bears may

feel threatened if surprised.

Watch for bear sign—fresh

tracks, digging, and scats. Detour around the area if

bears or their fresh sign are observed.

NEVER approach a bear cub.

Adult female brown bears are very defensive and may be

aggressive, making threatening gestures (laying ears

back, huffing, chopping jaws, stomping feet) and

possibly making bluff charges. Bears have a tolerance

range which, when encroached upon, may trigger an

attack. Keep a distance of at least 100 yards (100 m)

between you and bears.

Bears are omnivorous,

eating both vegetable and animal matter, so don’t

encourage bears by leaving food or garbage around camp.

When bears associate food with humans, they may lose

their fear of humans. Food-conditioned bears are very

dangerous.

In established

campgrounds, keep your campsite clean and lock food in

the trunk of your vehicle. Don’t leave dirty utensils

around the campsite, and don’t cook or eat in tents.

After eating, place garbage in containers provided at

the campground.

In the backcountry,

establish camps away from animal or walking trails, and

near large, sparsely branched trees that can be climbed

should it become necessary. Choose another area if fresh

bear sign is present. Cache food away from your tent,

preferably suspended from a tree that is 100 yards (100

m) downwind of camp. Use bear-proof or airtight

containers for storing food and other attractants.

Freeze-dried foods are lightweight and relatively

odor-free. Pack out all noncombustible garbage. Always

have radio communication and emergency transportation

available at remote base or work camps in case of

accidents or medical emergencies.

Don’t take dogs into the

backcountry. The sight or smell of a dog may attract a

bear and stimulate an attack. Most dogs are no match for

a bear. When in trouble, the dog may come running back

to the owner with the bear in pursuit. Trained guarding

dogs are an exception and may be very useful in

ID="LinkTarget_1135" detecting and chasing away bears in

the immediate area.

Bear Confrontations.

If a brown bear is seen at a distance, make a wide

detour. Keep upwind if possible so the bear can pick up

human scent and recognize human presence. If a detour or

retreat is not possible, wait until the bear moves away

from the path. Always leave an escape route and never

harass a bear.

If a brown bear is

encountered at close range, keep calm and assess the

situation. A bear rearing on its hind legs is not always

aggressive. If it moves its head from side to side it

may only be trying to pick up scent and focus its eyes.

Remain still and speak in low tones. This may indicate

to the animal that there is no threat. Assess the

surroundings before taking action. There is no

guaranteed life-saving method of handling an aggressive

bear, but some behavior patterns have proven more

successful than others.

Do not run. Most

bears can run as fast as a racehorse, covering 30 to 40

feet (9 to 12 m) per second. Quick, jerky movements can

trigger an attack. If an aggressive bear is met in a

wooded area, speak softly and back slowly toward a tree.

Climb a good distance up the tree. Adult grizzlies don’t

climb as a rule, but large ones can reach up to 10 feet

(3 m). Defend yourself in a tree with branches or a boot

heel if necessary.

Occasionally, bears will

bluff by charging within a few yards (m) of an

unfortunate hiker. Sometime they charge and veer away at

the last second. If you are charged, attempt to stand

your ground. The bear may perceive you as a greater

threat than it is willing to tackle and may leave the

area.

As a last resort when

attacked by a grizzly/brown bear, passively resist by

playing dead. Drop to the ground face down, lift your

legs up to your chest, and clasp both hands over the

back of your neck. Wearing a pack will shield your body.

Brown bears have been known to inflict only minor

injuries under these circumstances. It takes courage to

lie still and quiet, but resistance is usually useless.

Many people who work in or

frequent bear habitat carry firearms for personal

protection. Although not a popular solution, it is

justifiable to kill a bear that is attacking a human.

Economics of Damage and Control

The US Endangered Species

Act dictates that the bear be favored and protected. In

terms of a natural resource, individual grizzlies are

considered worth $500,000 by some accounts, and the

$20,000 penalty for a wrongful death underscores the

importance of management. In terms of tourism,

recreation, film making, photography, hunting, and all

the other cultural and art values of the grizzly, each

bear is certainly worth the half million dollars cited

above. Yet in Montana, where the future of the grizzly

is in jeopardy, their value was only recently raised

from $50 to $500. Bear parts have illegally sold for as

much as $250 per front claw, $200 per paw, $10,000 for

the hide, $500 for the skull, and $30,000 for the gall

bladder. Poachers would likely be fined only $10,000 if

caught.

One hope for brown bears

may be found in the private sector—people who value

bears highly and contribute to organizations that

support proper bear management. Damage prevention and

control costs could also be met by such organizations.

Because hunting is no longer widely practiced, revenues

for bear management have declined. Wildlife agencies

must develop a higher value for the brown bear and

divert fees collected from hunting other species to meet

the rising costs of bear management.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Julie Mae

Ringelberg for help in preparing this manuscript. Tim

Manley and Mile Madel of the Montana Department of Fish,

Wildlife, and Parks provided advice and information.

Figure 1 drawn by Clint E.

Chapman, University of Nebraska.

For Additional Information

Best, R. C. 1976. Ecological energetics of the polar

bears ( Ursus maritimus Phipps 1974). M.S. Thesis. Univ.

Guelph, Ontario. 136pp.

Boddicker, M. L. 1986.

Black bears. Pages C5C15 in R. M. Timm, ed. Prevention

and control of wildlife damage. Univ. Nebraska, Coop.

Ex. Lincoln.

Bromley, M. ed. 1989.

Bear-people conflicts: proceedings of a symposium on

management strategies. Northwest Terr. Dep. Renew.

Resour. Yellowknife. 246pp.

Brown, D. E. 1985. The

grizzly in the Southwest: documentary of an extinction.

Univ. Oklahoma Press, Norman. 274pp.

Bunnell, F. L., and D. E.

N. Tait. 1981. Population dynamics of

bears—implications. Pages 75-98 in C. W. Fowler and T.

D. Smith, eds. Dynamics of large mammal populations.

John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Clarkson, P. L., and L.

Sutterlin. 1984. Bear essentials. Ursid Res. Center,

Missoula, Montana. 67pp.

Craighead, J. J., and J.

A. Mitchell. 1982. Grizzly bear. Pages 515-556 in J. A.

Chapman and G. A. Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North

America: biology, management, and economics. The Johns

Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Graf, L. H., P. L.

Clarkson, and J. A. Nagy. 1992. Safety in bear country:

a reference manual. Rev. ed. Northwest Terr. Dep. Renew.

Resour. Yellowknife. 135pp.

Herrero, S. 1985. Bear

attacks: their causes and avoidance. Winchester Press,

Piscataway, New Jersey. 287pp.

Jonkel, C. J. 1986. How to

live in bear country. Ursid Res. Center Pub. 1. 33pp.

Jonkel, C. J. 1987. Brown

bear. Pages 456-473 in M. Novak, J. A. Baker, M. E.

Obbard, and B. Malloch, eds. Wild furbearer management

and conservation in North America. Ontario Ministry Nat.

Resour. Toronto.

Jonkel, C. J. 1993. Bear

trapping drugging and handling manual. US Fish Wildl.

Serv. Missoula, Montana.

McNamee, T. 1984. The

grizzly bear. A. Knopf Pub., New York. 308pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

01/23/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|