|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: Foxes |

|

|

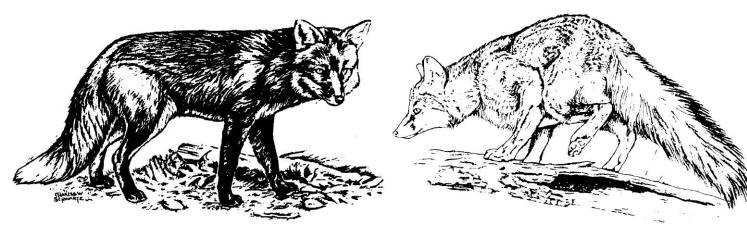

Fig. 1. Red fox, Vulpes

vulpes (left) and gray fox, Urocyon

cinereoargenteus (right).

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

-

Exclusion

Net wire fence. Electric fence.

-

Cultural Methods

Protect livestock and poultry during most vulnerable

periods (for example, shed lambing, farrowing pigs

in protective enclosures).

-

Frightening

Flashing lights and exploders may provide temporary

protection.

Well-trained livestock guarding dogs may be

effective in some situations.

-

Repellents

None are registered for livestock protection.

-

Toxicants

M-44® sodium cyanide mechanical ejection device, in

states where registered.

-

Fumigants

Gas cartridges for den fumigation, where registered.

-

Trapping

Steel leghold traps. Cage or box traps. Snares.

-

Shooting

Predator calling techniques. Aerial hunting.

-

Other Methods

Den hunting. Remove young foxes from dens to reduce

predation by adults.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Identification

The red fox (Vulpes

vulpes) is the most common of the foxes native to

North America. Most depredation problems are associated

with red foxes, although in some areas gray foxes (Urocyon

cinereoargenteus) can cause problems. Few damage

complaints have been associated with the swift fox (V.

velox), kit fox (V. macrotis), or Arctic fox (Alopex

lagopus).

The red fox is dog-like in

appearance, with an elongated pointed muzzle and large

pointed ears that are usually erect and forward. It has

moderately long legs and long, thick, soft body fur with

a heavily furred, bushy tail (Fig. 1). Typically, red

foxes are colored with a light orange-red coat, black

legs, lighter-colored underfur and a white-tipped tail.

Silver and cross foxes are color phases of the red fox.

In North America the red fox weighs about 7.7 to 15.4

pounds (3.5 to 7.0 kg), with males on average 2.2 pounds

(1 kg) heavier than females.

Gray foxes weigh 7 to 13

pounds (3.2 to 5.9 kg) and measure 32 to 45 inches (81

to 114 cm) from the nose to the tip of the tail (Fig.

1). The color pattern is generally salt-and-pepper gray

with buffy underfur. The sides of the neck, back of the

ears, legs, and feet are rusty yellow. The tail is long

and bushy with a black tip.

Other species of foxes

present in North America are the Arctic fox, swift fox,

and kit fox. These animals are not usually associated

with livestock and poultry depredation because they

typically eat small rodents and lead a secretive life in

remote habitats away from people, although they may

cause site-specific damage problems.

Range Range

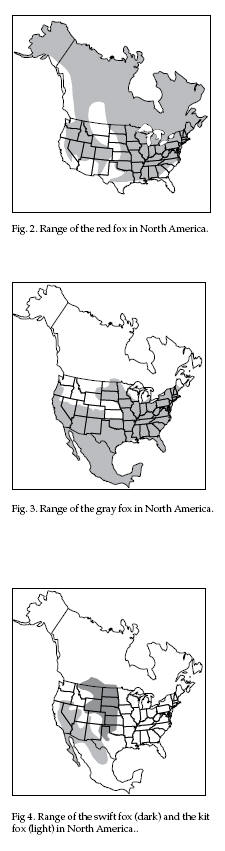

Red foxes occur over most

of North America, north and east from southern

California, Arizona, and central Texas. They are found

throughout most of the United States with the exception

of a few isolated areas (Fig. 2).

Gray foxes are found

throughout the eastern, north central, and southwestern

United States They are found throughout Mexico and most

of the southwestern United States from California

northward through western Oregon (Fig. 3).

Kit foxes are residents of

arid habitats. They are found from extreme southern

Oregon and Idaho south along the Baja Peninsula and

eastward through southwestern Texas and northern Mexico

(Fig. 4).

The present range of swift

foxes is restricted to the central high plains. They are

found in Kansas, the Oklahoma panhandle, New Mexico,

Texas, Nebraska, South Dakota, Wyoming, and Colorado

(Fig. 4).

As its name indicates, the

Arctic fox occurs in the arctic regions of North America

and was introduced on a number of islands in the

Aleutian chain.

Habitat

The red fox is adaptable to most habitats

within its range, but usually prefers open country with

moderate cover. Some of the highest fox densities

reported are in the north-central interspersed with

farmlands. The range of the red fox has expanded in

recent years to fill habitats formerly occupied by

coyotes (Canis latrans). The reduction of coyote numbers

in many sagebrush/grassland areas of Montana and Wyoming

has resulted in increased fox numbers. Red foxes have

also demonstrated their adaptability by establishing

breeding populations in many urban areas of the United

States, Canada, and Europe. Gray foxes prefer more dense

cover such as thickets, riparian areas, swamp land, or

rocky pinyon-cedar ridges. In eastern North America,

this species is closely associated with edges of

deciduous forests. Gray foxes can also be found in urban

areas where suitable habitat exists.

Food Habits

Foxes are opportunists,

feeding mostly on rabbits, mice, bird eggs, insects, and

native fruits. Foxes usually kill animals smaller than a

rabbit, although fawns, pigs, kids, lambs, and poultry

are sometimes taken. The fox’s keen hearing, vision,

and sense of smell aid in detecting prey. Foxes stalk

even the smallest mice with skill and patience. The

stalk usually ends with a sudden pounce onto the prey.

Red foxes sometimes kill more than they can eat and bury

food in caches for later use. All foxes feed on carrion

(animal carcasses) at times.

General Biology,

Reproduction, and Behavior Foxes are crepuscular

animals, being most active during the early hours of

darkness and very early morning hours. They do move

about during the day, however, especially when it is

dark and overcast.

Foxes are solitary animals

except from the winter breeding season through

midsummer, when mates and their young associate closely.

Foxes have a wide variety of calls. They may bark,

scream, howl, yap, growl, or make sounds similar to a

hiccup. During winter a male will often give a yelling

bark, “wo-wo-wo,” that seems to be important in

warning other male foxes not to intrude on its

territory. Red foxes may dig their own dens or use

abandoned burrows of a woodchuck or badger. The same

dens may be used for several generations. Gray foxes

commonly use wood piles, rocky outcrops, hollow trees,

or brush piles as den sites. Foxes use their urine and

feces to mark their territories.

Mating in red foxes

normally occurs from mid-January to early February. At

higher latitudes (in the Arctic) mating occurs from late

February to early March. Estrus in the vixen lasts 1 to

6 days, followed by a 51- to 53-day gestation period.

Fox pups can be born from March in southern areas to May

in the arctic zones. Red foxes generally produce 4 to 9

pups. Gray foxes usually have 3 to 7 pups per litter.

Arctic foxes may have from 1 to 14 pups, but usually

have 5 or 6. Foxes disperse from denning areas during

the fall months and establish breeding areas in vacant

territories, sometimes dispersing considerable

distances.

Damage and Damage Identification

Foxes may cause serious

problems for poultry producers. Turkeys raised in large

range pens are subject to damage by foxes. Losses may be

heavy in small farm flocks of chickens, ducks, and

geese. Young pigs, lambs, and small pets are also killed

by foxes. Damage can be difficult to detect because the

prey is usually carried from the kill site to a den

site, or uneaten parts are buried. Foxes usually attack

the throat of young livestock, but some kill by

inflicting multiple bites to the neck and back. Foxes do

not have the size or strength to hold adult livestock or

to crush the skull and large bones of their prey. They

generally prefer the viscera and often begin feeding

through an entry behind the ribs. Foxes will also

scavenge carcasses, making the actual cause of death

difficult to determine.

Pheasants, waterfowl,

other game birds, and small game mammals are also preyed

upon by foxes. At times, fox predation may be a

significant mortality factor for upland and wetland

birds, including some endangered species.

Rabies outbreaks are most

prevalent among red foxes in southeastern Canada and

occasionally in the eastern United States. The incidence

of rabies in foxes has declined substantially since the

mid-1960s for unexplained reasons. In 1990, there were

only 197 reported cases of fox rabies in the United

States as compared to 1,821 for raccoons and 1,579 for

skunks. Rabid foxes are a threat to humans, domestic

animals, and wildlife.

Legal Status

Foxes in the United States

are listed as furbearers or given some status as game

animals by most state governments. Most states allow for

the taking of foxes to protect private property. Check

with your state wildlife agency for regulations before

undertaking fox control measures.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods Exclusion

Construct net wire fences

with openings of 3 inches (8 cm) or less to exclude red

foxes. Bury the bottom of the fence 1 to 2 feet (0.3 m

to 0.9 m) with an apron of net wire extending at least

12 inches (30 cm) outward from the bottom. A top or roof

of net wire may also be necessary to exclude all foxes,

since some will readily climb a fence.

A 3-wire electric fence

with wires spaced 6 inches, 12 inches, and 18 inches (15

cm, 31 cm, and 46 cm) above the ground can repel red

foxes. Combination fences that incorporate net and

electric wires are also effective.

Cultural Methods

The protection of

livestock and poultry from fox depredation is most

important during the spring denning period when adults

are actively acquiring prey for their young. Watch for

signs of depredation during the spring, especially if

there is a history of fox depredation. Foxes, like other

wild canids, will often return to established denning

areas year after year. Foxes frequently den in close

proximity to human habitation. Dens may be located close

to farm buildings, under haystacks or patches of cover,

or even inside hog lots or small pastures used for

lambing. Because of the elusive habits of foxes, dens in

these locations may not be noticed until excessive

depredations have occurred.

The practice of shed

lambing and farrowing in protected enclosures can be

useful in preventing fox depredation on young livestock.

Also, removal of livestock carcasses from production

areas can make these areas less attractive to predators.

Frightening

Foxes readily adapt to

noise-making devices such as propane exploders, timed

tape recordings, amplifiers, or radios, but such devices

may temporarily reduce activity in an area.

Flashing lights, such as a

rotating beacon or strobe light, may also provide

temporary protection in relatively small areas or in

livestock or poultry enclosures. Combinations of

frightening devices used at irregular intervals should

provide better protection than use of a single device

because animals may have more difficulty in adapting to

these disturbances.

When properly trained,

some breeds of dog, such as Great Pyrenees and Akbash

dogs, have been useful in preventing predation on sheep.

The effectiveness of dogs, even the “guard dog”

breeds, seems to depend entirely on training and the

individual disposition of the dog.

Toxicants

The M-44®, a sodium

cyanide mechanical ejection device, is registered for

control of red and gray foxes nationwide by

USDA-APHIS-ADC personnel, and in some states by

certified pesticide applicators. Information on the

safe, effective use of sodium cyanide is available from

the appropriate state agency charged with the

registration of pesticides. M-44s are generally set

along trails and at crossings regularly used by foxes.

Fumigants

Gas cartridges made by

USDA-APHIS-ADC are registered for fumigating the dens of

coyotes, pocket gophers, ground squirrels, and other

burrowing rodents. Special Local Needs permits 24(c) are

available in North and South Dakota and Nebraska for gas

cartridge fumigation of fox dens. State and local

regulations should be consulted before using den

fumigants.

Trapping

Trapping is a very

effective and selective control method. A great deal of

expertise is required to effectively trap foxes.

Trapping by inexperienced people may serve to educate

foxes, making them very difficult to catch, even by

experienced trappers. Traps suitable for foxes are the

Nos. 1 1/2, 1 3/4, and 2 double coilspring trap and the

Nos. 2 and 3 double longspring trap. Traps with offset

and padded jaws cause less injury to confined animals

and facilitate the release of nontarget captures. State

and provincial wildlife agencies regulate the traps and

sets that can be used for trapping. Consult your local

agency personnel for restrictions that pertain to your

area.

Proper set location is

important when trapping foxes. Sets made along trails,

at entrances to fields, and near carcasses are often

most productive (Fig. 5). Many different sets are

successful, and can minimize the risk of nontarget

capture. One of the best is the dirt-hole set (Fig. 6).

Dig a hole about 6 inches (15 cm) deep and 3 inches (8

cm) in diameter at a downward angle just behind the spot

where the trap is to be placed. Four to five drops of

scent should be placed in the back of the hole. Move

back from the bait hole and dig a hole 2 inches (5 cm)

deep that is large enough to accommodate the trap and

chain. Fasten the trap chain to a trap stake with a

chain swivel and drive the stake directly under the

place where the trap is set. Fold and place the chain

under or beside the trap. Set the trap about 1/2 inch

(1.3 cm) below the ground. Adjust the tension device on

the trap to eliminate the capture of lighter animals.

When the set is completed, the pan of the trap should be

approximately 5 inches (13 cm) from the entrance of the

hole with the pan slightly offset from the center of the

hole (Fig. 6).

Cover the area between the

jaws and over the trap pan with a piece of waxed paper,

light canvas, or light screen wire. The trap must be

firmly placed so that it does not move or wobble. The

entire trap should be covered lightly with sifted soil

up to the original ground level.

Fox scents and lures can

be homemade, but this requires some knowledge of scent

making as described in various trapping books.

Commercial trap scents can be purchased from most

trapping suppliers (see Supplies and Materials).

Experiment with various baits and scents to discover the

combination of odors that will be most appropriate for

your area.

Equipment needed for

trapping foxes includes traps, a sifter with a 3/16- or

1/2-inch screen (0.5 or 1.3 cm), trap stakes, trowel,

gloves (which should be used only for trapping), a 16-

to 20ounce (448-to 560-g) carpenter�s hammer with

straight claws, and a bottle of scent. Remove the

factory oil finish on the traps by boiling the traps in

water and vinegar or by burying the traps in moist soil

for one to two weeks until lightly rusted. The traps

should then be dyed with commercially available trap dye

to prevent further corrosion. Do not allow the traps and

other trapping equipment to come in contact with

gasoline, oil, or other strong-smelling and

contaminating materials. Cleanliness of equipment is

absolutely necessary for consistent trapping success.

Cage traps are sometimes

effective for capturing juvenile red foxes living in

urban areas. It is uncommon to trap an adult red fox in

a cage or a box trap; however, kit and swift foxes can

be readily captured using this method.

Snares made from

1/16-inch, 5/64-inch, and 3/32-inch (0.15 cm, 0.2 cm,

and 0.25 cm) cable can be very effective for capturing

both red and gray foxes. Snares are generally set in

trails or in crawl holes (under fences) that are

frequented by foxes. The standard loop size for foxes is

about 6 inches (15 cm) with the bottom of the loop about

10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 cm) above ground level (Fig.

7). Trails leading to and from den sites and to

carcasses being fed on by foxes make excellent locations

for snares.

Shooting

Harvest of foxes by sport

hunters and fur trappers is another method of reducing

fox populations in areas where damage is occurring.

Livestock and poultry producers who have predation

problems during the late fall and winter can sometimes

find private fur trappers willing to hunt or trap foxes

around loss sites. Depredations are usually most severe,

however, during the spring when furs are not saleable,

and it is difficult to interest private trappers at that

time.

Artificial rabbit distress

calls can be used to decoy foxes to within rifle or

shotgun range. Select a spot that faces into the wind,

at the edge of a clearing or under a bush on a slight

rise where visibility is good. Blow the call at 1/2-to

1-minute intervals, with each call lasting 5 to 10

seconds. If a fox appears, remain motionless and do not

move the rifle or shotgun until ready to shoot. If a fox

does not appear in about 20 minutes, move to a new spot

and call again.

Aerial hunting can be used

in some western states to remove problem foxes. This

activity is closely regulated and is usually limited to

USDA-APHIS-ADC personnel or individuals with special

permits from the state regulatory agency.

Den Hunting

Fox depredations often

increase during the spring whelping season. Damage may

be reduced or even eliminated by locating and removing

the young foxes from the den. Locate fox dens by

observing signs of fox activity and by careful

observation during the early and late hours of the day

when adult foxes are moving about in search of food.

Preferred denning sites are usually on a low rise facing

a southerly direction. When fox pups are several weeks

old, they will spend time outside the den in the early

morning and evening hours. They leave abundant signs of

their presence, such as matted vegetation and remnants

of food, including bits of bone, feathers, and hair.

Frequently used den sites have a distinctive odor.

Fox pups may be removed by

trapping or by fumigating the den with gas cartridges if

they are registered for your area. In some situations it

may be desirable to remove the pups without killing

them. The mechanical wire ferret has proved to be

effective in chasing the pups from the den without

harming them. This device consists of a long piece of

smooth spring steel wire with a spring and wooden plug

at one end and a handle at the other. This wire is

twisted through the den passageways, chasing foxes out

of other den openings where they can be captured by hand

or with dip nets. Small dogs are sometimes trained to

retrieve pups unharmed from dens. Wire-cage box traps

placed in the entrance of the den can also be useful for

capturing young foxes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Norman C.

Johnson, whose chapter “Foxes” in the 1983 edition

of this manual provided much of the information used in

this section. F. Sherman Blom, Ronald A. Thompson, and

Judy Loven (USDA-APHIS-ADC) provided useful comments.

Figure 1 from Schwartz and

Schwartz (1981) adapted by Jill Sack Johnson.

Figures 2, 3, and 4

courtesy of Pam Tinnin.

Figure 5 courtesy of Bob

Noonan.

Figures 6 and 7 courtesy

of Tom Krause.

For Additional

Information

Burt, W. H., and R. P.

Grossenheider. 1976. A field guide to mammals, 3d ed.

Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. 289 pp.

Foreyt, W. J. 1980. A live

trap for multiple capture of coyote pups from dens. J.

Wildl. Manage. 44:487-88.

Fritzell, E. K., and K. J.

Haroldson. 1982. Urocyon cinereoargenteus. Mammal. Sp.

189:1-8.

Dolbeer, R. A., N. R.

Holler, and D. W. Hawthorne. 1994. Identification and

control of wildlife damage. Pages 474-506 in T. A.

Bookhout ed. Research and management techniques for

wildlife and habitats. The Wildl. Soc., Bethesda,

Maryland.

Krause, T. 1982. NTA

trapping handbook — a guide for better trapping.

Spearman Publ. and Printing Co., Sutton, Nebraska. 206

pp.

Samuel, D. E., and B. B.

Nelson. 1982. Foxes. Pages 475-90 in J. A. Chapman and

G. A Feldhamer eds., Wild mammals of North America:

biology, management, and economics. The Johns Hopkins

Univ. Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri, rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp.

Storm, G. L., R. D.

Andrews, R. L. Phillips, R. A. Bishop, D. B. Siniff, and

J. R. Tester. 1976. Morphology, reproduction, dispersal

and mortality of midwestern red fox populations. Wildl.

Mono. No. 49. The Wildl. Soc., Inc., Washington, DC. 82

pp.

Storm, G. L., and K. P.

Dauphin. 1965. A wire ferret for use in studies of foxes

and skunks. J. Wildl. Manage. 29:625-26.

Voigt, D. R. 1987. Red

fox. Pages 379-93 in M. Novak, J. A. Baker, M. E. Obbard,

and B. Malloch eds., Wildlife Furbearer Management and

Conservation in North America. Ontario Ministry of Nat.

Resour.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

01/23/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|