|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: Coyotes |

|

|

Fig. 1. Coyote, Canis

latrans

Identification

In body form and size, the

coyote (Canis latrans) resembles a small collie dog,

with erect pointed ears, slender muzzle, and a bushy

tail (Fig. 1). Coyotes are predominantly brownish gray

in color with a light gray to cream-colored belly. Color

varies greatly, however, from nearly black to red or

nearly white in some individuals and local populations.

Most have dark or black guard hairs over their back and

tail. In western states, typical adult males weigh from

25 to 45 pounds (11 to 16 kg) and females from 22 to 35

pounds (10 to 14 kg). In the East, many coyotes are

larger than their western counterparts, with males

averaging about 45 pounds (14 kg) and females about 30

pounds (13 kg).

Coyote-dog and coyote-wolf

hybrids exist in some areas and may vary greatly from

typical coyotes in size, color, and appearance. Also,

coyotes in the New England states may differ in color

from typical western coyotes. Many are black, and some

are reddish. These colorations may partially be due to

past hybridization with dogs and wolves. True wolves are

also present in some areas of coyote range, particularly

in Canada, Alaska, Montana, northern Minnesota,

Wisconsin, and Michigan. Relatively few wolves remain in

the southern United States and Mexico.

Range

Historically, coyotes were

most common on the Great Plains of North America. They

have since extended their range from Central America to

the Arctic, including all of the United States (except

Hawaii), Canada, and Mexico.

Habitat

Many references indicate

that coyotes were originally found in relatively open

habitats, particularly the grasslands and sparsely

wooded areas of the western United States. Whether or

not this was true, coyotes have adapted to and now exist

in virtually every type of habitat, arctic to tropic, in

North America. Coyotes live in deserts, swamps, tundra,

grasslands, brush, dense forests, from below sea level

to high mountain ranges, and at all intermediate

altitudes. High densities of coyotes also appear in the

suburbs of Los Angeles, Pasadena, Phoenix, and other

western cities.

Food Habits

Coyotes often include many

items in their diet. Rabbits top the list of their

dietary components. Carrion, rodents, ungulates (usually

fawns), insects (such as grasshoppers), as well as

livestock and poultry, are also consumed. Coyotes

readily eat fruits such as watermelons, berries, and

other vegetative matter when they are available. In some

areas coyotes feed on human refuse at dump sites and

take pets (cats and small dogs).

Coyotes are opportunistic

and generally take prey that is the easiest to secure.

Among larger wild animals, coyotes tend to kill young,

inexperienced animals, as well as old, sick, or weakened

individuals. With domestic animals, coyotes are capable

of catching and killing healthy, young, and in some

instances, adult prey. Prey selection is based on

opportunity and a myriad of behavioral cues. Strong,

healthy lambs are often taken from a flock by a coyote

even though smaller, weaker lambs are also present.

Usually, the stronger lamb is on the periphery and is

more active, making it more prone to attack than a

weaker lamb that is at the center of the flock and

relatively immobile.

Coyote predation on

livestock is generally more severe during early spring

and summer than in winter for two reasons. First, sheep

and cows are usually under more intensive management

during winter, either in feedlots or in pastures that

are close to human activity, thus reducing the

opportunity for coyotes to take livestock. Second,

predators bear young in the spring and raise them

through the summer, a process that demands increased

nutritional input, for both the whelping and nursing

mother and the growing young. This increased demand

corresponds to the time when young sheep or beef calves

are on pastures or rangeland and are most vulnerable to

attack. Coyote predation also may increase during fall

when young coyotes disperse from their home ranges and

establish new territories.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Coyotes are most active at

night and during early morning hours (especially where

human activity occurs), and during hot summer weather.

Where there is minimal human interference and during

cool weather, they may be active throughout the day.

Coyotes bed in sheltered

areas but do not generally use dens except when raising

young. They may seek shelter underground during severe

weather or when closely pursued. Their physical

abilities include good eyesight and hearing and a keen

sense of smell. Documented recoveries from severe

injuries are indicative of coyotes’ physical endurance.

Although not as fleet as greyhound dogs, coyotes have

been measured at speeds of up to 40 miles per hour (64

km/hr) and can sustain slower speeds for several miles

(km).

Distemper, hepatitis,

parvo virus, and mange (caused by parasitic mites) are

among the most common coyote diseases. Rabies and

tularemia also occur and may be transmitted to other

animals and humans. Coyotes harbor numerous parasites

including mites, ticks, fleas, worms, and flukes.

Mortality is highest during the first year of life, and

few survive for more than 10 to 12 years in the wild.

Human activity is often the greatest single cause of

coyote mortality.

Coyotes usually breed in

February and March, producing litters about 9 weeks (60

to 63 days) later in April and May. Females sometimes

breed during the winter following their birth,

particularly if food is plentiful. Average litter size

is 5 to 7 pups, although up to 13 in a litter has been

reported. More than one litter may be found in a single

den; at times these may be from females mated to a

single male. As noted earlier, coyotes are capable of

hybridizing with dogs and wolves, but reproductive

dysynchrony and behaviors generally make it unlikely.

Hybrids are fertile, although their breeding seasons do

not usually correspond to those of coyotes.

Coyote dens are found in

steep banks, rock crevices, sinkholes, and underbrush,

as well as in open areas. Usually their dens are in

areas selected for protective concealment. Den sites are

typically located less than a mile (km) from water, but

may occasionally be much farther away. Coyotes will

often dig out and enlarge holes dug by smaller burrowing

animals. Dens vary from a few feet (1 m) to 50 feet (15

m) and may have several openings.

Both adult male and female

coyotes hunt and bring food to their young for several

weeks. Other adults associated with the denning pair may

also help in feeding and caring for the young. Coyotes

commonly hunt as singles or pairs; extensive travel is

common in their hunting forays. They will hunt in the

same area regularly, however, if food is plentiful. They

occasionally bury food remains for later use.

Pups begin emerging from

their den by 3 weeks of age, and within 2 months they

follow adults to large prey or carrion. Pups normally

are weaned by 6 weeks of age and frequently are moved to

larger quarters such as dense brush patches and/or

sinkholes along water courses. The adults and pups

usually remain together until late summer or fall when

pups become independent. Occasionally pups are found in

groups until the breeding season begins.

Coyotes are successful at

surviving and even flourishing in the presence of people

because of their adaptable behavior and social system.

They typically display increased reproduction and

immigration in response to human-induced population

reduction.

Damage and Damage Identification

Coyotes can cause damage

to a variety of resources, including livestock, poultry,

and crops such as watermelons. They sometimes prey on

pets and are a threat to public health and safety when

they frequent airport runways and residential areas, and

act as carriers of rabies. Usually, the primary concern

regarding coyotes is predation on livestock, mainly

sheep and lambs. Predation will be the focus of the

following discussion.

Since coyotes frequently

scavenge on livestock carcasses, the mere presence of

coyote tracks or droppings near a carcass is not

sufficient evidence that predation has taken place.

Other evidence around the site and on the carcass must

be carefully examined to aid in determining the cause of

death. Signs of a struggle may be evident. These may

include scrapes or drag marks on the ground, broken

vegetation, or blood in various places around the site.

The quantity of sheep or calf remains left after a kill

vary widely depending on how recently the kill was made,

the size of the animal killed, the weather, and the

number and species of predators that fed on the animal.

One key in determining

whether a sheep or calf was killed by a predator is the

presence or absence of subcutaneous (just under the

skin) hemorrhage at the point of attack. Bites to a dead

animal will not produce hemorrhage, but bites to a live

animal will. If enough of the sheep carcass remains,

carefully skin out the neck and head to observe tooth

punctures and hemorrhage around the punctures. Talon

punctures from large birds of prey will also cause

hemorrhage, but the location of these is usually at the

top of the head, neck, or back. This procedure becomes

less indicative of predation as the age of the carcass

increases or if the remains are scanty or scattered.

Coyotes, foxes, mountain

lions, and bobcats usually feed on a carcass at the

flanks or behind the ribs and first consume the liver,

heart, lungs, and other viscera. Mountain lions often

cover a carcass with debris after feeding on it. Bears

generally prefer meat to viscera and often eat first the

udder from lactating ewes. Eagles skin out carcasses on

larger animals and leave much of the skeleton intact.

With smaller animals such as lambs, eagles may bite off

and swallow the ribs. Feathers and “whitewash”

(droppings) are usually present where an eagle has fed.

Coyotes may kill more than

one animal in a single episode, but often will only feed

on one of the animals. Coyotes typically attack sheep at

the throat, but young or inexperienced coyotes may

attack any part of the body. Coyotes usually kill calves

by eating into the anus or abdominal area.

Dogs generally do not kill

sheep or calves for food and are relatively

indiscriminate in how and where they attack. Sometimes,

however, it is difficult to differentiate between dog

and coyote kills without also looking at other sign,

such as size of tracks (Fig. 2) and spacing and size of

canine tooth punctures. Coyote tracks tend to be more

oval-shaped and compact than those of common dogs. Nail

marks are less prominent and the tracks tend to follow a

straight line more closely than those of dogs. The

average coyote’s stride at a trot is 16 to 18 inches (41

to 46 cm), which is typically longer than that of a dog

of similar size and weight. Generally, dogs attack and

rip the flanks, hind quarters, and head, and may chew

ears. The sheep are sometimes still alive but may be

severely wounded.

Accurately determining

whether or not predation occurred and, if so, by what

species, requires a considerable amount of knowledge and

experience. Evidence must be gathered, pieced together,

and then evaluated in light of the predators that are in

the area, the time of day, the season of the year, and

numerous other factors. Sometimes even experts are

unable to confirm the cause of death, and it may be

necessary to rely on circumstantial information. For

more information on this subject, refer to the section

Procedures for Evaluating Predation on Livestock and

Wildlife, in this book.

Legal Status

The status of coyotes

varies depending on state and local laws. In some

states, including most western states, coyotes are

classified as predators and can be taken throughout the

year whether or not they are causing damage to

livestock. In other states, coyotes may be taken only

during specific seasons and often only by specific

methods, such as trapping. Night shooting with a

spotlight is usually illegal. Some state laws allow only

state or federal agents to use certain methods (such as

snares) to take coyotes. Some states have a provision

for allowing the taking of protected coyotes (usually by

special permit) when it has been documented that they

are preying on livestock. In some instances producers

can apply control methods, and in others, control must

be managed by a federal or state agent. Some eastern

states consider the coyote a game animal, a furbearer,

or a protected species.

Fig.

2. Footprints of canid predators Fig.

2. Footprints of canid predators

Federal statutes that

pertain to wildlife damage control include the Federal

Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA),

which deals with using toxicants, and the Airborne

Hunting Act, which regulates aerial hunting.

Laws regulating coyote

control are not necessarily uniform among states or even

among counties within a state, and they may change

frequently. A 1989 Supreme Court action established that

it was not legal to circumvent the laws relative to

killing predators, even to protect personal property

(livestock) from predation.

Large dog

Damage Prevention and

Control Methods For managing coyote damage, a variety of

control methods must be available since no single method

is effective in every situation. Success usually

involves an integrated approach, combining good

husbandry practices with effective control methods for

short periods of time. Regardless of the means used to

stop damage, the focus should be on damage prevention

and control rather than elimination of coyotes. It is

neither wise nor practical to kill all coyotes. It is

important to try to prevent coyotes from killing calves

or sheep for the first time. Once a coyote has killed

livestock, it will probably continue to do so if given

the opportunity. Equally important is taking action as

quickly as possible to stop coyotes from killing after

they start.

Exclusion

Most coyotes readily cross

over, under, or through conventional livestock fences. A

coyote’s response to a fence is influenced by various

factors, including the coyote’s experience and

motivation for crossing the fence. Total exclusion of

all coyotes by fencing, especially from large areas, is

highly unlikely since some eventually learn to either

dig deeper or climb higher to defeat a fence. Good

fences, however, can be important in reducing predation,

as well as increasing the effectiveness of other damage

control methods (such as snares, traps, or guarding

animals).

Recent developments in

fencing equipment and design have made this technique an

effective and economically practical method for

protecting sheep from predation under some grazing

conditions. Exclusion fencing may be impractical in

western range sheep ranching operations.

Net-Wire

Fencing. Net fences in good repair will deter many

coyotes from entering a pasture. Horizontal spacing of

the mesh should be less than 6 inches (15 cm), and

vertical spacing less than 4 inches (10 cm). Digging

under a fence can be discouraged by placing a barbed

wire at ground level or using a buried wire apron (often

an expensive option). The fence should be about 5 1/2

feet (1.6 m) high to discourage coyotes from jumping

over it. Climbing can usually be prevented by adding a

charged wire at the top of the fence or installing a

wire overhang. Net-Wire

Fencing. Net fences in good repair will deter many

coyotes from entering a pasture. Horizontal spacing of

the mesh should be less than 6 inches (15 cm), and

vertical spacing less than 4 inches (10 cm). Digging

under a fence can be discouraged by placing a barbed

wire at ground level or using a buried wire apron (often

an expensive option). The fence should be about 5 1/2

feet (1.6 m) high to discourage coyotes from jumping

over it. Climbing can usually be prevented by adding a

charged wire at the top of the fence or installing a

wire overhang.

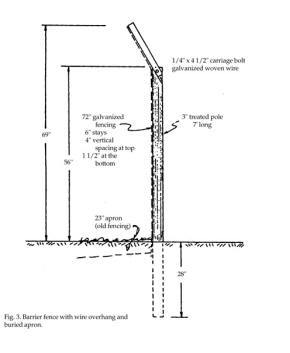

Barrier fences with wire

overhangs and buried wire aprons were tested in Oregon

and found effective in keeping coyotes out of sheep

pastures (Fig. 3). The construction and materials for

such fencing are usually expensive. Therefore, fences of

this type are rarely used except around corrals,

feedlots, or areas of temporary sheep confinement.

Electric Fencing. Electric

fencing, used for years to manage livestock, has

recently been revolutionized by the introduction of new

energizers and new fence designs from Australia and New

Zealand. The chargers, now also manufactured in the

United States, have high output with low impedance, are

resistant to grounding, present a minimal fire hazard,

and are generally safe for livestock and humans. The

fences are usually constructed of smooth, high-tensile

wire stretched to a tension of 200 to 300 pounds (90 to

135 kg). The original design of electric fences for

controlling predation consisted of multiple, alternately

charged and grounded wires, with a charged trip wire

installed just above ground level about 8 inches (20 cm)

outside the main fence to discourage digging. Many

recent designs have every wire charged.

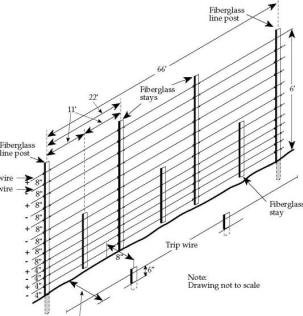

The number of spacings

between wires varies considerably. A fence of 13 strands

gave complete protection to sheep from coyote predation

in tests at the USDA’s US Sheep Experiment Station (Fig.

4). Other designs of fewer wires were effective in some

studies, ineffective in others.

The amount of labor and

installation techniques required vary with each type of

fencing. High-tensile wire fences require adequate

bracing at corners and over long spans. Electric fencing

is easiest to install on flat, even terrain. Labor to

install a high-tensile electric fence may be 40% to 50%

less than for a conventional livestock fence.

Labor to keep electric

fencing functional can be significant. Tension of the

wires must be maintained, excessive vegetation under the

fence must be removed to prevent grounding, damage from

livestock and wildlife must be repaired, and the charger

must be checked regularly to ensure that it is

operational.

Charged wire Ground wire

Ground level

Fig. 5. Existing

woven-wire livestock fence modified with electrified

wire.

Coyotes and other

predators occasionally become “trapped” inside electric

fences. These animals receive a shock as they enter the

pasture and subsequently avoid approaching the fence to

escape. In some instances the captured predator may be

easy to spot and remove from the pasture, but in others,

particularly in large pastures with rough terrain, the

animal may be difficult to remove.

Electric Modification of

Existing Fences. The cost to completely replace old

fences with new ones, whether conventional or electric,

can be substantial. In instances where existing fencing

is in reasonably good condition, the addition of one to

several charged wires can significantly enhance the

predator-deterring ability of the fence and its

effectiveness for controlling livestock (Fig. 5). A

charged trip wire placed 6 to 8 inches (15 to 230 cm)

above the ground about 8 to 10 inches (20 to 25 cm)

outside the fence is often effective in preventing

coyotes from digging and crawling under. This single

addition to an existing fence is often the most

effective and economical way to fortify a fence against

coyote passage.

If coyotes are climbing or

jumping a fence, charged wires can be added to the top

and at various intervals. These wires should be offset

outside the fence. Fencing companies offer offset

brackets to make installation relatively simple. The

number of additional wires depends on the design of the

original fence and the predicted habits of the

predators.

Portable Electric Fencing.

The advent of safe, high-energy chargers has led to the

development of a variety of portable electric fences.

Most are constructed with thin strands of wire running

through polyethylene twine or ribbon, commonly called

polywire or polytape. The polywire is available in

single and multiple wire rolls or as mesh fencing of

various heights. It can be quickly and easily installed

to serve as a temporary corral or to partition off

pastures for controlled grazing.

Perhaps the biggest

advantage of portable electric fencing is the ability to

set up temporary pens to hold livestock at night or

during other predator control activities. Portable

fencing increases livestock management options to avoid

places or periods of high predation risk. Range sheep

that are not accustomed to being fenced, however, may be

difficult to contain in a portable fence.

Fencing and Predation

Management. The success of various types of fencing in

keeping out predators has ranged from poor to excellent.

Density and behavior of coyotes, terrain and vegetative

conditions, availability of prey, size of pastures,

season of the year, design of the fence, quality of

construction, maintenance, and other factors all

interplay in determining how effective a fence will be.

Fencing is most likely to be cost-effective where the

potential for predation is high, where there is

potential for a high stocking rate, or where electric

modification of existing fences can be used.

Fencing can be effective

when incorporated with other means of predation control.

For example, combined use of guarding dogs and fencing

has achieved a greater degree of success than either

method used alone. An electric fence may help keep a

guarding dog in and coyotes out of a pasture. If an

occasional coyote does pass through a fence, the

guarding dog can keep it away from the livestock and

alert the producer by barking.

Fencing can also be used

to concentrate predator activity at specific places such

as gateways, ravines, or other areas where the animals

try to gain access. Traps and snares can often be set at

strategic places along a fence to effectively capture

predators. Smaller pastures are easier to keep free from

predators than larger ones encompassing several square

miles (km2).

Fencing is one of the most

beneficial investments in predator damage control and

livestock management where practical factors warrant its

use.

As a final note, fences

can pose problems for wildlife. Barrier fences in

particular exclude not only predators, but also many

other wildlife species. This fact should be considered

where fencing intersects migration corridors for

wildlife. Ungulates such as deer may attempt to jump

fences, and they occasionally become entangled in the

top wires.

Cultural

Methods and Habitat Modification

At the present time, there

are no documented differences in the vulnerability of

various breeds of sheep to coyote or dog predation

because there has been very little research in this

area. Generally, breeds with stronger flocking behaviors

are less vulnerable to predators.

A possible cause of

increased coyote predation to beef cattle calves is the

increased use of cattle dogs in herding. Cows herded by

dogs may not be as willing to defend newborn calves from

coyotes as those not accustomed to herding dogs.

Flock or Herd Health.

Healthy sheep flocks and cow/calf herds have higher

reproductive rates and lower overall death losses.

Coyotes often prey on smaller lambs. Poor nutrition

means weaker or smaller young, with a resultant

increased potential for predation. Ewes or cows in good

condition through proper nutrition will raise stronger

young that may be less vulnerable to coyote predation.

Record Keeping. Good

record-keeping and animal identification systems are

invaluable in a livestock operation for several reasons.

From the standpoint of coyote predation, records help

producers identify loss patterns or trends to provide

baseline data that will help determine what type and

amount of coyote damage control is economically

feasible. Records also aid in identifying critical

problem areas that may require attention. They may show,

for example, that losses to coyotes are high in a

particular pasture in early summer, thus highlighting

the need for preventive control in that area.

Counting sheep and calves

regularly is important in large pastures or areas with

heavy cover where dead livestock could remain unnoticed.

It is not unusual for producers who do not regularly

count their sheep to suffer fairly substantial losses

before they realize there is a problem. Determining with

certainty whether losses were due to coyotes or to other

causes may become impossible.

Season and Location of

Lambing or Calving. Both season and location of lambing

and calving can significantly affect the severity of

coyote predation on sheep or calves. The highest

predation losses of sheep and calves typically occur

from late spring through September due to the food

requirements of coyote pups. In the Midwest and East,

some lambing or calving occurs between October and

December, whereas in most of the western states lambing

or calving occurs between February and May. By changing

to a fall lambing or calving program, some livestock

producers have not only been able to diversify their

marketing program, but have also avoided having a large

number of young animals on hand during periods when

coyote predation losses are typically highest.

Shortening lambing and

calving periods by using synchronized or group breeding

may reduce predation by producing a uniform lamb or calf

crop, thus reducing exposure of small livestock to

predation. Extra labor and facilities may be necessary,

however, when birthing within a concentrated period.

Some producers practice early weaning and do not allow

young to go to large pastures, thus reducing the chance

of coyote losses. This also gives orphaned and weak

young a greater chance to survive.

The average beef cattle

calf production is about 78% nationwide. First-calf

heifers need human assistance to give birth to a healthy

calf about 40% of the time. Cow/calf producers who

average 90% to 95% calf crops generally check their

first-calf heifers every 2 hours during calving. Also,

most good producers place first-calf heifers in small

pastures (less than 160 acres [64 ha]). When all cows

are bred to produce calves in a short, discreet (e.g.

60-day) period, production typically increases and

predation losses decrease. The birth weight of calves

born to first-calf heifers can be decreased by using

calving-ease bulls, thus reducing birthing complications

that often lead to coyote predation.

Producers who use lambing

sheds or pens for raising sheep and small pastures or

paddocks for raising cattle have lower predation losses

than those who lamb or calve in large pastures or on

open range. The more human presence around sheep, the

lower the predation losses. Confining sheep entirely to

buildings virtually eliminates predation losses.

Corrals. Although

predation can occur at any time, coyotes tend to kill

sheep at night. Confining sheep at night is one of the

most effective means of reducing losses to predation.

Nevertheless, some coyotes and many dogs are bold enough

to enter corrals and kill sheep. A “coyote-proof” corral

is a wise investment. Coyotes are more likely to attack

sheep in unlighted corrals than in corrals with lights.

Even if the corral fence is not coyote-proof, the mere

fact that the sheep are confined reduces the risk of

predation. Penning sheep at night and turning them out

at mid-morning might reduce losses. In addition, coyotes

tend to be more active and kill more sheep on foggy or

rainy days than on sunny days. Keeping the sheep penned

on foggy or rainy days may be helpful.

Aside from the benefits of

livestock confinement, there are some problems

associated it. Costs of labor and materials associated

with building corrals, herding livestock, and feeding

livestock must be considered. In addition, the

likelihood of increased parasite and disease problems

may inhibit adoption of confinement as a method of

reducing damage.

Carrion Removal. Removal

and proper disposal of dead sheep and cattle are

important since livestock carcasses tend to attract

coyotes, habituating them to feed on livestock.

Some producers reason that

coyotes are less likely to kill livestock if there is

carrion available. This may be a valid preventative

measure if an adequate supply of carrion can be

maintained far away from livestock. If a coyote becomes

habituated to a diet of livestock remains, however, it

may turn to killing livestock in the absence of

carcasses. Wherever there is easily accessible carrion,

coyotes seem to gather and predation losses are higher.

Conversely, where carrion is generally not available,

losses are lower. A study in Canada showed that the

removal of livestock carcasses significantly reduced

overwinter coyote populations and shifted coyote

distributions out of livestock areas.

Habitat Changes. Habitat

features change in some areas, depending on seasonal

crop growth. Some cultivated fields are devoid of

coyotes during winter but provide cover during the

growing season, and a corresponding increase in

predation on nearby livestock may occur.

The creation of nearly 40

million acres (16 million ha) of Conservation Reserve

Program (CRP) acres may benefit many species of

wildlife, including predators. These acres harbor prey

for coyotes and foxes, and an increase in predator

populations can reasonably be predicted. Clearing away

weeds and brush from CRP areas may reduce predation

problems since predators usually use cover in their

approach to livestock. Generally, the more open the area

where livestock are kept, the less likely that coyote

losses will occur. Often junk piles are located near

farmsteads. These serve as good habitat for rabbits and

other prey and may bring coyotes into close proximity

with livestock, increasing the likelihood for

opportunistic coyotes to prey on available livestock.

Removing junk piles may be a good management practice.

Pasture Selection. If

sheep or beef cattle are not lambed or calved in sheds

or lots, the choice of birthing pastures should be made

with potential coyote predation problems in mind. Lambs

and calves in remote or rugged pastures are usually more

vulnerable to coyote predation than those in closer,

more open, and smaller pastures. In general, a

relatively small, open, tightly fenced pasture that can

be kept under close surveillance is a good choice for

birthing livestock that are likely targets of coyotes.

Past experience with predators as well as weather and

disease considerations should also serve as guides in

the selection of birthing pastures.

A factor not completely

understood is that, at times, coyotes and other

predators will kill in one pasture and not in another.

Therefore, changing pastures during times of loss may

reduce predation. There may seem to be a relationship

between size of pasture and predator losses, with higher

loss rates reported in larger pastures. In reality, loss

rates may not be related as much to pasture size as to

other local conditions such as slope, terrain, and human

populations. Hilly or rugged areas are typically

sparsely populated by humans and are characterized by

large pastures. These conditions are ideal for coyotes.

Sheep pastures that

contain or are adjacent to streams, creeks, and rivers

tend to have more coyote problems than pastures without

such features. Water courses serve as hunting and travel

lanes for coyotes.

Herders. Using herders

with sheep or cattle in large pastures can help reduce

predation, but there has been a trend away from herders

in recent years because of increasing costs and a

shortage of competent help. Nevertheless, tended flocks

or herds receive closer attention than untended

livestock, particularly in large pastures, and problems

can be solved before they become serious. We recommend

two herders per band of range sheep. If herders aren’t

used, daily or periodic checking of the livestock is a

good husbandry practice.

Frightening Devices and Repellents

Frightening devices are

useful for reducing losses during short periods or until

predators are removed. The devices should not be used

for long periods of time when predation is not a

problem. To avoid acclimation you can increase both the

degree and duration of effectiveness by varying the

position, appearance, duration, or frequency of the

frightening stimuli, or using them in various

combinations. Many frightening methods have been

ridiculed in one way or another; nevertheless, all of

the techniques discussed here have helped producers by

saving livestock and/or buying some time to institute

other controls.

Lights. A study involving

100 Kansas sheep producers showed that using lights

above corrals at night had the most marked effect on

losses to coyotes of all the devices examined. Out of 79

sheep killed by coyotes in corrals, only three were

killed in corrals with lights. Nearly 40% of the

producers in the study used lights over corrals. There

was some indication in the study that sheep losses to

dogs were higher in lighted corrals, but the sample size

for dog losses was small and the results inconclusive.

Most of the producers (80%) used mercury vapor lights

that automatically turned on at dusk and off at dawn.

Another advantage of

lighted corrals is that coyotes are more vulnerable when

they enter the lighted area. Coyotes often establish a

fairly predictable pattern of killing. When this happens

in a lighted corral, it is possible for a producer to

wait above or downwind of the corral and to shoot the

coyote as it enters. Red or blue lights may make the

ambush more successful since coyotes appear to be less

frightened by them than by white lights.

Revolving or flashing the

lights may enhance their effectiveness in frightening

away predators. There is some speculation that the old

oil lamps used in highway construction repelled coyotes,

presumably because of their flickering effect.

Bells and Radios. Some

sheep producers place bells on some or all of their

sheep to discourage predators. Where effects have been

measured, however, no difference in losses was detected.

Some producers use a radio

tuned to an all-night station to temporarily deter

coyotes, dogs, and other predators.

Vehicles. Parking cars or

pickups in the area where losses are occurring often

reduces predation temporarily. Effectiveness can be

improved or extended by frequently moving the vehicle to

a new location. Some producers place a replica of a

person in the vehicle when losses are occurring in the

daylight. If predators continue to kill with vehicles in

place, the vehicle serves as a comfortable blind in

which to wait and shoot offending predators.

Propane Exploders. Propane

exploders produce loud explosions at timed intervals

when a spark ignites a measured amount of propane gas.

On most models, the time between explosions can vary

from about 1 minute to 15 minutes. Their effectiveness

at frightening coyotes is usually only temporary, but it

can be increased by moving exploders to different

locations and by varying the intervals between

explosions. In general, the timer on the exploder should

be set to fire every 8 to 10 minutes, and the location

should be changed every 3 or 4 days. In cattle pastures,

these devices should be placed on rigid stands above the

livestock. Normally, the exploder should be turned on

just before dark and off at daybreak, unless coyotes are

killing livestock during daylight hours. Motion sensors

are now available and likely improve their

effectiveness, though it is still only temporary.

Exploders are best used to reduce losses until more

permanent control or preventive measures can be

implemented. In about 24 coyote depredation complaints

over a 2-year period in North Dakota, propane exploders

were judged to be successful in stopping or reducing

predation losses until offending coyotes could be

removed. “Success time” of the exploders appears to

depend a great deal on how well they are tended by the

livestock producer.

Strobe

Lights and Sirens. The USDA’s Denver Wildlife Research

Fig. 6. Electronic Guard frightening device

Center developed a

frightening device called the Electronic Guard (EG)

(Fig. 6). The EG consists of a strobe light and siren

controlled by a variable interval timer that is

activated at night with a photoelectric cell. In tests

conducted in fenced pastures, predation was reduced by

about 89%. The device is used in Kansas and other states

to protect cows/calves from coyote predation. Most

research on the effectiveness of this device, however,

has been done on sheep operations. Suggestions for using

the unit differ for pastured sheep and range operations.

To use the EG in fenced

pastures (farm flocks):

Place EGs above the ground

on fence posts, trees, or T-posts so they can be heard

and seen at greater distances and to prevent livestock

from damaging them. Position EGs so that rain water

cannot enter them and cause a malfunction. Locate EGs so

that light can enter the photocell port or window. If

positioned in deep shade, they may not turn on or off at

the desired times. The number of EGs used to protect

sheep in fenced pastures depends on pasture size,

terrain features, and the amount and height of

vegetation in or around the pasture. In general, at

least two units should be used in small (20 to 30 acres

[8 to 12 ha]), level, short-grass pastures. Three to

four units should be used in larger (40 to 100 acres [16

to 40 ha]), hilly, tall grass, or wooded pastures. Don’t

use EGs in pastures larger than about 100 acres (40 ha)

because their effective range is limited. The device

could be useful in larger pastures when placed near

areas where sheep congregate and bed at night. EGs

should be placed on high spots, where kills have been

found, at the edge of wooded areas, near or on

bedgrounds, or near suspected coyote travelways. They

should be moved to different locations every 10 to 14

days to reduce the likelihood of coyotes getting used to

them To use the EG in open range (herded or range

sheep):

The number of EGs used

will depend on the number of sheep in the band and the

size of the bedground. Four units should be used to

protect bands of 1,000 ewes and their lambs. When

possible, place one EG in the center of the bedground

and the other three around the edge of the bedground.

Try to place the units on coyote travelways. EGs should

be placed on high points, ridge tops, edges of

clearings, or on high rocks or outcroppings. Hang the

devices on tree limbs 5 to 7 feet (1.5 to 2.1 m) above

ground level. If used above timberline or in treeless

areas, hang them from a tripod of poles. Herders who bed

their sheep tightly will have better results than those

who allow sheep to bed over large areas. Sheep that are

bedded about 200 yards (166 m) or less in diameter, or

are spread out not more than 200 to 400 yards (166 to

332 m) along a ridge top, can usually be protected with

EGs. Repellents. The notion of repelling coyotes from

sheep or calves is appealing, and during the 1970s,

university and government researchers tested a wide

variety of potentially repellent chemical compounds on

sheep. Both olfactory (smell) and gustatory (taste)

repellents were examined. The underlying objective was

to find a compound that, when applied to sheep, would

prevent coyotes from killing them. Tests were conducted

with various prey species including rabbits, chickens,

and sheep. Some repellents were applied by dipping

target animals in them, others were sprayed on, and some

were applied in neck collars or ear tags.

Coyotes rely heavily on

visual cues while stalking, chasing, and killing their

prey. Taste and smell are of lesser importance in

actually making the kill. These factors may in part

account for the fact that the repellent compounds were

not able to consistently prevent coyotes from killing,

although some of the repellents were obviously offensive

to coyotes and prevented them from consuming the killed

prey. Several compounds were tested on sheep under field

conditions, but none appeared to offer significant,

prolonged protection.

If an effective chemical

repellent were to be found, the obstacles in bringing it

to industry use would be significant. The compound would

not only need to be effective, but also persistent

enough to withstand weathering while posing no undue

risk to the sheep, other animals, or the environment. It

would also have to withstand the rigorous Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA) approval process.

High-frequency sound has

also been tested as a repellent for coyotes, but the

results were no more encouraging than for chemical

repellents. Coyotes, like dogs, responded to particular

sound frequencies and showed some aversion to sounds

broadcast within one foot (30 cm) of their ear.

Researchers, however, were unable to broadcast the sound

a sufficient distance to test the effects under field

conditions.

Aversive Conditioning. The

objective of aversive conditioning is to feed a coyote a

preylike bait laced with an aversive agent that causes

the coyote to become ill, resulting in subsequent

avoidance of the prey. Most of the research on this

technique has involved the use of lithium chloride, a

salt, as the aversive agent.

Aversive conditioning is

well documented for averting rodents from food sources,

but significant problems must be overcome before the

method can be used to reduce coyote predation on sheep.

Coyotes must be induced to eat sheeplike baits that have

been treated with the aversive chemical. The chemical

must cause sufficient discomfort, such as vomiting, to

cause coyotes to avoid other baits. Furthermore, the

avoidance must be transferred to live sheep and must

persist long enough without reinforcement for the method

to offer realistic protection to sheep.

To date, pen and field

tests with aversive conditioning have yielded

conflicting and inconclusive results. It does not appear

that aversive conditioning is effective in reducing

predation, but additional field tests would be useful.

Guarding

Animals.

Livestock Guarding Dogs. A

livestock guarding dog is one that generally stays with

sheep or cattle without harming them and aggressively

repels predators. Its protective behaviors are largely

instinctive, but proper rearing plays a part. Breeds

most commonly used today include the Great Pyrenees,

Komondor, Anatolian Shepherd, and Akbash Dog (Fig. 7).

Other Old World breeds used to a lesser degree include

Maremma, Sharplaninetz, and Kuvasz. Crossbreeds are also

used.

The characteristics of

each sheep operation will dictate the number of dogs

required for effective protection from predators. If

predators are scarce, one dog is sufficient for most

fenced pasture operations. Range operations often use

two dogs per band of sheep. The performance of

individual dogs will differ based on age and experience.

The size, topography, and habitat of the pasture or

range must also be considered. Relatively flat, open

areas can be adequately covered by one dog. When brush,

timber, ravines, and hills are in the pasture, several

dogs may be required, particularly if the sheep are

scattered. Sheep that flock and form a cohesive unit,

especially at night, can be protected by one dog more

effectively than sheep that are continually scattered

and bedded in a number of locations.

Fig. 7. Livestock guarding

dog (Akbash dog)

The goal with a new puppy

is to channel its natural instincts to produce a mature

guardian dog with the desired characteristics. This is

best accomplished by early and continued association

with sheep to produce a bond between the dog and sheep.

The optimum time to acquire a pup is between 7 and 8

weeks of age. The pup should be separated from litter

mates and placed with sheep, preferably lambs, in a pen

or corral from which it can’t escape. This socialization

period should continue with daily checks from the

producer until the pup is about 16 weeks old. Daily

checks don’t necessarily include petting the pup. The

primary bond should be between the dog and the sheep,

not between the dog and humans. The owner, however,

should be able to catch and handle the dog to administer

health care or to manage the livestock. At about 4

months, the pup can be released into a larger pasture to

mingle with the other sheep.

A guarding dog will likely

include peripheral areas in its patrolling. Some have

been known to chase vehicles and wildlife and threaten

children and cyclists. These activities should be

discouraged. Neighbors should be alerted to the

possibility that the dog may roam onto their property

and that some predator control devices such as traps,

snares, and M-44s present a danger to it. Many counties

enforce stringent laws regarding owner responsibility

for damage done by roaming dogs. It is in the best

interests of the owner, dog, and community to train the

dog to stay in its designated area.

The use of guarding dogs

does not eliminate the need for other predation control

actions. They should, however, be compatible with the

dog’s behavior. Toxicants (including some insecticides

and rodenticides) used to control various pest species

can be extremely hazardous to dogs and are therefore not

compatible with the use of guarding dogs.

The M-44 is particularly

hazardous to dogs. Some people have successfully trained

their dogs to avoid M-44s by allowing the dog to set off

an M-44 filled with pepper or by rigging the device to a

rat trap. The unpleasant experience may teach the dog to

avoid M-44s, but the method is not fool-proof—one error

by the dog, and the result is usually fatal. With the

exception of toxic collars, which are not legal in all

states, toxicants should not be used in areas where

guarding dogs are working unless the dog is chained or

confined while the control takes place.

Dogs caught in a steel

trap set for predators are rarely injured seriously if

they are found and released within a reasonable period

of time. If snares and traps are used where dogs are

working, the producer should: (1) encourage the use of

sets and devices that are likely not to injure the dog

if it is caught, and (2) know where traps and snares are

set so they can be checked if a dog is missing. Aerial

hunting, as well as calling and shooting coyotes, should

pose no threat to guarding dogs. Ensuring the safety of

the dog is largely the producer’s responsibility.

Dogs may be viewed as a

first line of defense against predation in sheep and

cow/calf operations in some cases. Their effectiveness

can be enhanced by good livestock management and by

eliminating predators with suitable removal techniques.

Donkeys. Although the

research has not focused on donkeys as it has on

guarding dogs, they are gaining in popularity as

protectors of sheep and goat flocks in the United

States. A recent survey showed that in Texas alone, over

2,400 of the 11,000 sheep and goat producers had used

donkeys as guardians.

The terms donkey and burro

are synonymous (the Spanish translation of donkey is

burro) and are used interchangeably. Donkeys are

generally docile to people, but they seem to have an

inherent dislike of dogs and other canids, including

coyotes and foxes. The typical response of a donkey to

an intruding canid may include braying, bared teeth, a

running attack, kicking, and biting. Most likely it is

acting out of aggression toward the intruder rather than

to protect the sheep. There is little information on a

donkey’s effectiveness with noncanid predators such as

bears, mountain lions, bobcats, or birds of prey.

Reported success of

donkeys in reducing predation is highly variable.

Improper husbandry or rearing practices and unrealistic

expectations probably account for many failures. Donkeys

are significantly cheaper to obtain and care for than

guarding dogs, and they are probably less prone to

accidental death and premature mortality than dogs. They

may provide a longer period of useful life than a

guarding dog, and they can be used with relative safety

in conjunction with snares, traps, M-44s, and toxic

collars.

Researchers and livestock

producers have identified several key points to consider

when using a donkey for predation control:

Use only a jenny or a

gelded jack. Intact jacks are too aggressive and may

injure livestock. Some jennies and geldings may also

injure livestock. Select donkeys from medium-sized

stock. Use only one donkey per group of sheep. The

exception may be a jenny with a foal. When two or more

adult donkeys are together or with a horse, they usually

stay together, not necessarily near the sheep. Also

avoid using donkeys in adjacent pastures since they may

socialize across the fence and ignore the sheep. Allow

about 4 to 6 weeks for a naive donkey to bond to the

sheep. Stronger bonding may occur when a donkey is

raised from birth with sheep. Avoid feeds or supplements

containing monensin or lasolacid. They are poisonous to

donkeys. Remove the donkey during lambing, particularly

if lambing in confinement, to avoid injuries to lambs or

disruption of the lamb-ewe bond. Test a new donkey’s

response to canids by challenging it with a dog in a pen

or small pasture. Discard donkeys that don’t show overt

aggression to an intruding dog. Use donkeys in smaller

(less than 600 acres [240 ha]), relatively open pastures

with not more than 200 to 300 head of livestock. Large

pastures with rough terrain and vegetation and widely

scattered livestock lessen the effectiveness of a

donkey. Llamas. Like donkeys, llamas have an inherent

dislike of canids, and a growing number of livestock

producers are successfully using llamas to protect their

sheep. A recent study of 145 ranches where guard llamas

were used to protect sheep revealed that average losses

of sheep to predators decreased from 26 to 8 per year

after llamas were employed. Eighty percent of the

ranchers surveyed were “very satisfied” or “satisfied”

with their llamas. Llamas reportedly bond with sheep

within hours and offer advantages over guarding dogs

similar to those described for donkeys.

Other Animals. USDA’s

Agricultural Research Service tested the bonding of

sheep to cattle as a method of protecting sheep from

coyote predation. There was clearly some protection

afforded the sheep that remained near cattle. Whether

this protection resulted from direct action by the

cattle or by the coyotes’ response to a novel stimulus

is uncertain. Later studies with goats, sheep, and

cattle confirmed that when either goats or sheep

remained near cattle, they were protected from predation

by coyotes. Conversely, goats or sheep that grazed apart

from cattle, even those that were bonded, were readily

preyed on by coyotes.

There are currently no

research data available on the ideal ratio of cattle to

sheep, the breeds of cattle, age of cattle most likely

to be used successfully, or on the size of bonded groups

to obtain maximum protection from predation.

Multispecies grazing offers many advantages for optimum

utilization of forage, and though additional study and

experience is needed, it may also be a tool for coyote

damage control.

Any animal that displays

aggressive behavior toward intruding coyotes may offer

some benefit in deterring predation. Other types of

animals reportedly used for predation control include

goats, mules, and ostriches. Coyotes in particular are

suspicious of novel stimuli. This behavior is most

likely the primary reason that many frightening tactics

show at least temporary effectiveness.

Toxicants

Pesticides have

historically been an important component in an

integrated approach to controlling coyote damage, but

their use is extremely restricted today by federal and

state laws. All pesticides used in the United States

must be registered with the EPA under the provisions of

FIFRA and must be used in accordance with label

directions. Increasingly restrictive regulations

implemented by EPA under the authority of FIFRA, the

National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), presidential

order, and the Endangered Species Act have resulted in

the near elimination of toxicants legally available for

predator damage control.

The only toxicants

currently registered for mammalian predator damage

control are sodium cyanide, used in the M-44 ejector

device, and Compound 1080 (sodium monofluoroacetate),

for use in the livestock protection collar. These

toxicants are Restricted Use Pesticides and may be used

only by certified pesticide applicators. Information on

registration status and availability of these products

in individual states may be obtained from the respective

state’s department of agriculture.

Sodium Cyanide in the

M-44. The M-44 is a spring-activated device used to

expel sodium cyanide into an animal’s mouth. It is

currently registered by EPA for use by trained personnel

in the control of depredating coyotes, foxes, and dogs.

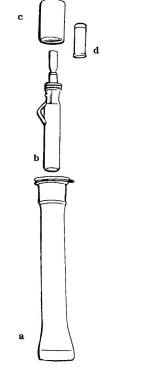

The M-44 consists of a

capsule holder wrapped in an absorbent material, an

ejector mechanism, a capsule containing approximately

0.9 grams of a powdered sodium cyanide mixture, and a 5-

to 7-inch (15- to 18-cm) hollow stake (Fig. 8). For most

effective use, set M-44s in locations similar to those

for good trap sets. Drive the hollow stake into the

ground. Cock the ejector unit and secure it in the

stake. Screw the wrapped capsule holder containing the

cyanide capsule onto the ejector unit, and apply fetid

meat bait to the capsule holder. Coyotes attracted by

the bait will try to bite the baited capsule holder.

When the M-44 is pulled, the

Fig. 8. The M-44 device consists of the (a) base,

(b) ejector, (c) capsule

holder, and (d) cyanide-containing plastic capsule.

spring-activated plunger

propels sodium cyanide into the animal’s mouth,

resulting in death within a few seconds.

The M-44 is very selective

for canids because of the attractants used and the

unique requirement that the device be triggered by

pulling on it. While the use of traps or snares may

present a hazard to livestock, M-44s can be used with

relative safety in pastures where livestock are present.

Although not recommended, they can also be used in the

presence of livestock guarding dogs if the dogs are

first successfully conditioned to avoid the devices.

This can be done by allowing them to pull an M-44 loaded

with pepper. An additional advantage of M-44s over traps

is their ability to remain effective during rain, snow,

and freezing conditions.

While M-44s can be used

effectively as part of an integrated damage control

program, they do have several disadvantages. Because

canids are less responsive to food-type baits during

warm weather when natural foods are usually abundant,

M-44s are not as effective during warmer months as they

are in cooler weather. M-44s are subject to a variety of

mechanical malfunctions, but these problems can be

minimized if a regular maintenance schedule is followed.

A further disadvantage is the tendency for the cyanide

in the capsules to absorb moisture over time and to

cake, becoming ineffective. Maximum effectiveness of

M-44s is hampered by the requirement to follow 26 use

restrictions established by the EPA in the interest of

human and environmental safety. The M-44 is not

registered for use in all states, and in those where it

is registered, the state may impose additional use

restrictions. A formal training program is required

before use of M-44s. Some states allow its use only by

federal ADC specialists, whereas other states may allow

M-44s to be used by trained and certified livestock

producers.

1080 Livestock Protection

Collar.

The livestock protection

collar (LP collar or toxic collar) is a relatively new

tool used to selectively kill coyotes that attack sheep

or goats. Collars are placed on sheep or goats that are

pastured where coyotes are likely to attack. Each collar

contains a small quantity (300 mg) of Compound 1080

solution. The collars do not attract coyotes, but

because of their design and position on the throat, most

attacking coyotes will puncture the collar and ingest a

lethal amount of the toxicant. Unlike sodium cyanide,

1080 is slow-acting, and a coyote ingesting the toxicant

will not exhibit symptoms or die for several hours. As a

result, sheep or goats that are attacked are usually

killed. The collar is registered only for use against

coyotes and may be placed only on sheep or goats.

The LP collar must be used

in conjunction with specific sheep and goat husbandry

practices to be most effective. Coyote attacks must be

directed or targeted at collared livestock. This may be

accomplished by temporarily placing a “target” flock of

perhaps 20 to 50 collared lambs or kids and their

uncollared mothers in a pasture where coyote predation

is likely to occur, while removing other sheep or goats

from that vicinity. In situations where LP collars have

been used and found ineffective, the common cause of

failure has been poor or ineffective targeting. It is

difficult to ensure effective targeting if depredations

are occurring infrequently. In most instances, only a

high and regular frequency of depredations will justify

spending the time, effort, and money necessary to become

trained and certified, purchase collars, and use them

properly.

The outstanding advantage

in using the LP collar is its selectivity in eliminating

individual coyotes that are responsible for killing

livestock. The collar may also be useful in removing

depredating coyotes that have eluded other means of

control. Disadvantages include the cost of collars

(approximately $20 each) and livestock that must be

sacrificed, more intensive management practices, and the

costs and inconvenience of complying with use

restrictions, including requirements for training,

certification, and record keeping. One use restriction

limits the collars to use in fenced pastures only. They

cannot be used to protect sheep on open range. Also,

collars are not widely available, because they are

registered for use in only a few states.

Fumigants

Carbon monoxide is an

effective burrow fumigant recently re-registered by the

EPA. Gas cartridges, which contain 65% sodium nitrate

and 35% charcoal, produce carbon monoxide, carbon

dioxide, and other noxious gases when ignited. They were

registered by the EPA in 1981 for control of coyotes in

dens only. This is the only fumigant currently

registered for this purpose.

Trapping

There are many effective

methods for trapping coyotes, and success can be

enhanced by considering several key points. Coyotes

learn from past events that were unpleasant or

frightening, and they often avoid such events in the

future. In spring and summer, most coyotes limit their

movements to a small area, but in late summer, fall, and

winter they may roam over a larger area. Coyotes follow

regular paths and crossways, and they prefer high hills

or knolls from which they can view the terrain. They

establish regular scent posts along their paths, and

they depend on their ears, nose, and eyes to sense

danger.

The following describes

one method of trapping that has proven effective for

many beginners.

Items Needed to Set a

Coyote Trap:

-

One 5-gallon (19-l)

plastic bucket to carry equipment.

-

Two No. 3 or No. 4

traps per set.

-

One 18-to 24-inch

(46-to 61-cm) stake for holding both traps in place.

-

Straight claw hammer

to dig a hole in the ground for trap placement and

to pound the stake into the ground.

-

Leather gloves to

protect fingers while digging the trap bed.

-

Cloth (or canvas) feed

sack to kneel on while digging a trap bed and

pounding the stake.

-

Roll of plastic

sandwich bags to cover and prevent soil from getting

under the pan of the trap.

-

Screen sifter for

sifting soil over the traps.

-

Rib bone for leveling

off soil over the traps once they are set in place

and covered.

-

Bottle of coyote urine

to attract the coyote to the set (keep urine away

from other equipment).

Locating the Set. Coyotes

travel where walking is easy, such as along old roads,

and they have preferred places to travel, hunt, rest,

howl, and roam. Do not set traps directly in a trail but

to one side where coyotes may stop, such as on a

hilltop, near a gate, or where cover changes. Make the

set on level ground to ensure that the coyote walks

across level ground to it.

Good locations for a set

are often indicated by coyote tracks. The following are

good locations on most farms and ranches for setting

traps: high hills and saddles in high hills; near

isolated land features or isolated bales of hay; trail

junctions, fences, and stream crossings; pasture roads,

livestock trails, waterways, game trails, and dry or

shallow creek beds; near pond dams, field borders, field

corners, groves of trees, and eroded gullies; sites near

animal carcasses, bone or brush piles; and under rim

rocks.

Making the Set. Place

three to five trap sets near the area where coyotes have

killed livestock.

-

First, observe the

area where the losses are occurring and look for

tracks and droppings to determine the species

responsible. Study the paths used by predators. If

you have 4 hours to spend setting traps, spend at

least 3 of them looking for coyote sign.

-

Decide where to place

the trap sets. Always place them in an open, flat

area because of wind currents, dispersion of scent,

and visibility. Never place traps uphill or downhill

from the coyote’s expected path of approach.

-

Look for open places

where coyote tracks indicate that the animal milled

around or stopped. Place the set upwind from the

path (or site of coyote activity) so the prevailing

wind will carry the scent across the area of

expected coyote activity.

-

Choose a level spot as

close as possible to, but not directly on, the

coyote’s path. The coyote’s approach should never be

over dry leaves, tall grass, stones, sticks, weeds,

or rough ground. Make each set where the coyote has

clear visibility as it approaches.

-

Place the set using

two No. 3 traps with a cold-shut chain repair link

affixed to the top of a steel stake. The link should

swivel around the stake top. The stake should be at

least 18 inches (46 cm) long, or longer if the soil

is loose. Use two stakes set at an angle to each

other if the soil will not hold with a single stake.

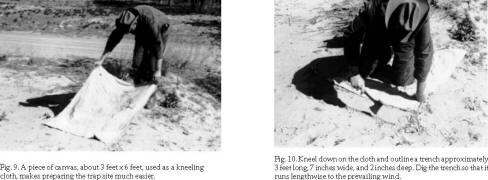

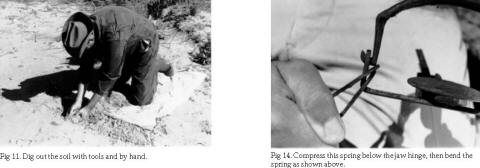

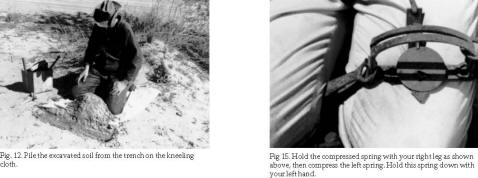

Figures 9 through 29

illustrate the procedures for making a set.

Fig. 9. A piece of canvas, about 3 feet x 6 feet, used

as a kneeling cloth, makes preparing the trap site much

easier.

Fig 20. Take out or add

soil until the trap pan and jaws are about 1/2 inch

below the level of the surrounding ground. Build a ridge

for the jaw opposite the trigger to sit on. On the side

of the trap that has the trigger, place soil under the

trap pan cover on either side of the trigger to hold the

pan cover up tight against the bottom of the jaws.

Fig 21. Stretch the pan cover tightly across the pan and

under the jaws. Pan and jaws should be level and flat.

In cold weather, plastic can be placed under the trap.

Place plastic baggies on each spring and mix table salt

with dry soil or peat moss to cover the trap. Set the

other trap as shown above. Place the pan cover so that

the dog or trigger can move upward without binding it

in. Anything that slows the action of the trap can cause

a miss or a toe hold.

Fig. 23. The trap should

be set about 1/4 inch below the level of the surrounding

ground. The set must look natural. The soil around the

trap and over the springs, chains, and stake should be

packed to the same firmness as the ground the coyote

walks on in its approach to the set. Only soft soil

should be directly over the trap pan within the set jaw

area. Use a curved stick, brush, or rib bone to level

soil over the trap.

Always bury the traps and stake in the ground using dry,

finely sifted soil. One of the most difficult aspects of

using traps is trapping when the ground is frozen,

muddy, wet, or damp. If the weather is expected to turn

cold and/or wet, you should use one or a combination of

the following materials in which to set and cover the

traps: Canadian sphagnum peat moss, very dry soil, dry

manure, buckwheat hulls, or finely chopped hay. A

mixture of one part table salt or calcium chloride with

three parts dry soil will prevent the soil from freezing

over the trap. When using peat moss or other dry, fluffy

material, cover the material with a thin layer of dry

soil mixed with 1/4 teaspoon of table salt. This will

blend the set with the surrounding soil and prevent the

wind from blowing peat moss away from the trap. As an

alternative, traps could be set in a bed of dry soil

placed over the snow or frozen ground.

Guiding Coyote Footsteps.

Use a few strategically placed dirt clods, sticks, small

rocks, or stickers around the set to guide the coyote’s

foot to the traps. Coyotes will tend to avoid the

obstacles and place their feet in bare areas. Do not use

this method to the extent that the set looks unnatural.

Care of Coyote Traps. New

traps can be used to trap coyotes, but better results

may be obtained by using traps that have been dyed.

Dyeing traps helps prevent rust and removes odors. Wood

chips or crystals for dyeing traps are available from

trapping supply outlets. Some trappers also wax their

traps to prevent them from rusting and to extend the

life of the traps.

Inevitably, rusting will

occur when traps are in use. It does not harm the traps,

but after their continued use the rust often will slow

the action of the trap and cause it to miss a coyote.

Traps also become contaminated with skunk musk,

gasoline, oil, blood, or other odors. It is important

that traps be clean and in good working condition.

Rusted traps should be cleaned with a wire brush to

ensure that the trigger and pan work freely. Check the

chain links for open links. File the triggers and

receivers to eliminate all rounded edges. Make any

adjustments necessary so that the pan will sit level and

the trap perform smoothly.

Size of Traps for Coyotes.

There are many suitable traps for catching coyotes. Both

the No. 3 and No. 4 are good choices. Many trappers

prefer a No. 3 coilspring round-jawed off-set trap. It

is a good idea to use superweld kinkless chain. The

length of chain varies depending on whether the trap is

staked or a drag is used. A longer chain should be used

with a drag. The off-set jaws are designed to reduce

broken foot bones, which can allow the coyote to escape

by wriggling out of the trap. Traps with coil springs

are good coyote traps, but they require more upkeep than

a double long-spring trap. The type and size of trap may

be regulated in each state. Body gripping traps are

dangerous and illegal in some states for catching

coyotes. When pet dogs might be present, use a

padded-jaw No. 3 double coilspring trap.

While additional testing

needs to be conducted, results of research to reduce

injury using padded-jaw traps have been encouraging. In

tests with No. 3 Soft-Catch® coilsprings, No. 3 NM

longsprings, and No. 4 Newhouse longsprings, capture

rates for coyotes were 95%, 100%, and 100%,

respectively. Soft-Catch traps caused the least visible

injury to captured coyotes.

Anchoring Traps. Chain

swivels are necessary for trapping coyotes. One swivel

at the stake, one in the middle of the chain, and one at

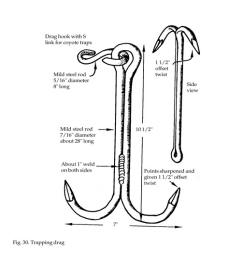

the trap are recommended. Drags (Fig. 30) instead of

stakes can be used where there is an abundance of brush

or trees or where the ground is too rocky to use a

stake. Use a long chain (5 feet [1.5 m] or more) on a

drag.

Lures and Scents. Coyotes

are interested in and may be attracted to odors in their

environment. Commercially available lures and scents or

natural odors such as fresh coyote, dog, or cat

droppings or urine may produce good results. Coyote

urine works the best.

Problems in Trapping

Coyotes.

A great deal of experience

is required to effectively trap coyotes. Trapping by

experienced or untrained people may serve to educate

coyotes, making them very difficult to catch, even by

experienced trappers. Coyotes, however, exhibit

individualized patterns of behavior. Many, but not all,

coyotes become trap-shy after being caught and then

escaping from a trap. There is a record of one coyote

having been caught eight times in the same set. Some

coyotes require considerably more time and thought to

trap than others. With unlimited time, a person could

trap almost any coyote.

If a coyote digs up or

springs a trap without getting caught, reset the trap in

the same place. Then carefully set one or two traps near

the first set. Use gloves and be careful to hide the

traps. Changing scents or using various tricks, such as

a lone feather as a visual attraction near a set, or a

ticking clock in a dirt hole set as an audible

attraction, may help in trying to catch wary coyotes.

Resetting Traps and

Checking Trap Sets. Once a coyote is caught at a set,

reset the trap in the same place. The odor and

disturbance at the set where a coyote has been caught

will often attract other coyotes. Sometimes other

coyotes will approach but not enter the circle where the

coyote was caught. If signs indicate that this has

happened, move the trap set outside of the circle. Leave

all sets out for at least 2 weeks before moving the

traps to a new location. Check the traps once every 24

hours, preferably in the morning around 9 or 10 o’clock.

Reapply the scent every 4 days, using 8 to 10 drops of

coyote urine.

Human Scent and Coyote

Trapping. Minimize human scent around trap sets as much

as possible.

Fig. 30. Trapping drag

If traps are being set in

warm months, make sure the trapper has recently bathed,

has clean clothes, and is not sweating. Leave no

unnecessary foreign odors, such as cigarette butts or

gum wrappers, near the set. Wear clean gloves and rubber

footwear while setting traps. A landowner may have an

advantage over a stranger who comes to set traps since

the coyotes are acquainted with the landowner’s scent

and expect him/her to be there. Coyotes have been known

to leave an area after encountering an unfamiliar human

scent.

Because of human scent,

coyotes are more difficult to catch with traps in wet or

humid weather. Wear gloves, wax traps, and take other

precautionary measures in areas where humans are not

commonly present, where wet weather conditions are

common, and where coyotes have been trapped for several

years and have learned to avoid traps.

Killing a Trapped Coyote.

A coyote will make its most desperate attempt to get out

of the trap as a person approaches. As soon as you get

within a few feet (m) of the coyote, check to see that

the trap has a firm hold on the coyote’s foot. If so,

shoot the coyote in the head, with a .22 caliber weapon.

It is often a good idea to reset the trap in the same

place. The blood from the coyote will not necessarily

harm the set as long as it is not on the trap or on the

soil over the reset traps. Reset the trap regardless of

the species of animal captured, skunks included.

Draw Stations. Draw

stations are natural areas or places set up

intentionally to draw coyotes to a particular location.