|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: Bobcats |

|

|

Identification

The bobcat (Lynx rufus),

alias “wildcat,” is a medium-sized member of the North

American cat family. It can be distinguished at a

distance by its graceful catlike movements, short (4- to

6-inches [10- to 15-cm]) “bobbed” tail, and round face

and pointed ears (Fig. 1). Visible at close distances

are black hair at the tip of the tail and prominent

white dots on the upper side of the ears. Body hair

color varies, but the animal’s sides and flanks are

usually brownish black or reddish brown with either

distinct or faint black spots. The back is commonly

brownish yellow with a dark line down the middle. The

chest and outside of the legs are covered with brownish

to light gray fur with black spots or bars. Bobcats

living at high elevations and in northern states and

Canada have relatively long hair. In southern states,

bobcats may have a yellowish or reddish cast on their

backs and necks.

Similar Species. The bobcat is two to three

times the size of the domestic cat and appears more

muscular and fuller in the body. Also, the bobcat’s hind

legs are proportionately longer to its front legs than

those of the domestic cat. The Canada lynx appears more

slender and has proportionately larger feet than the

bobcat. At close distances, the ear tufts of the lynx

can be seen. The tail of the lynx appears shorter than

the bobcat’s and its tip looks like it was dipped in

black paint. The bobcat’s tail is whitish below the tip.

Lynx commonly occur in Canada’s coniferous forests and,

rarely, in the Rocky Mountains. Where both species

occur, lynx occupy the more densely forested habitats

with heavy snow cover. Male bobcats tend to be larger

than females. Adult males range from 32 to 40 inches (80

to 102 cm) long and weigh from 14 to 40 pounds (6 to 18

kg) or more. Bobcats in Wyoming average between 20 and

30 pounds (9 and 14 kg). Nationwide, adult females range

from 28 to 32 inches (71 to 81 cm) long and weigh from 9

to 33 pounds (4 to 15 kg). Records indicate a tendency

for heavier bobcats in the northern portions of their

range and in western states at medium altitudes. The

skull has 28 teeth. Milk teeth are replaced by permanent

teeth when kittens are 4 to 6 months old. Females have 6

mammae.

Range

and Habitat Range

and Habitat

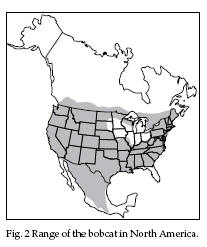

The bobcat occurs in a

wide variety of habitats from the Atlantic to the

Pacific ocean and from Mexico to northern British

Columbia (Fig. 2). It occurs in the 48 contiguous

states. The bobcat is as adapted to subtropical forests

as it is to dense shrub and hardwood cover in temperate

climates. Other habitats include chaparral, wooded

streams, river bottoms, canyon-lands, and coniferous

forests to 9,000 feet (2,743 m). Bobcats prefer areas

where these native habitat types are interspersed with

agriculture and escape cover (rocky outcrops) close by.

The bobcat has thrived where agriculture is interspersed

through the above native habitat types, as in southern

Canada. Food Habits Bobcats are capable of hunting and

killing prey that range from the size of a mouse to that

of a deer. Rabbits, tree squirrels, ground squirrels,

woodrats, porcupines, pocket gophers, and ground hogs

comprise most of their diet. Opossums, raccoon, grouse,

wild turkey, and other ground-nesting birds are also

eaten. Occasionally, insects and reptiles can be part of

the bobcat’s diet. In Canada, the snowshoe hare is the

bobcat’s favorite fare. Bobcats occasionally kill

livestock. They also resort to scavenging.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Bobcats are secretive,

shy, solitary, and seldom seen in the wild. They are

active during the day but prefer twilight, dawn, or

night hours. Bobcats tend to travel well-worn animal

trails, logging roads, and other paths. They use their

acute vision and hearing for locating enemies and prey.

Bobcats do not form lasting pair bonds. Mating can occur

between most adult animals. In Wyoming, female bobcats

reach sexual maturity within their first year but males

are not sexually mature until their second year.

Nationwide, breeding can occur from January to June. In

Wyoming, breeding typically begins in February and the

first estrus cycle in mid- March. The gestation period

in bobcats ranges from 50 to 70 days, averaging 62 days.

Nationwide, young are born

from March to July, with litters as late as October. The

breeding season may be affected by latitude, altitude,

and longitude, as well as by characteristics of each

bobcat population. In Wyoming, births peak mid-May to

mid-June and can occur as late as August or September.

These late litters may be from recycling or late-cycling

females, probably yearlings. In Utah, births may peak in

April or May. In Arkansas, births may peak as early as

March. Bobcats weigh about 2/3 pound (300 g) at birth.

Litters contain from 2 to 4 kittens. Kittens nurse for

about 60 days and may accompany their mother through

their first winter. Although young bobcats grow very

quickly Fig. 2 Range of the bobcat in North America.

C-37 during their first 6 months, males may not be fully

grown until 1 1/2 years and females until 2 years of

age. Bobcats may live for at least 12 years in the wild.

Bobcats reach densities of

about 1 per 1/4 square mile (0.7 km2) on some of the

Gulf Coast islands of the southeastern United States.

Densities vary from about 1 per 1/2 square mile (1.3

km2) in the coastal plains to about 1 cat per 4 square

miles (10.7 km2) in portions of the Appalachian

foothills. Mid-Atlantic and midwestern states usually

have scarce populations of bobcats. The social

organization and home range of bobcats can vary with

climate, habitat type, availability of food, and

predators. Bobcats are typically territorial and will

maintain the same territories throughout their lives.

One study showed home ranges in south Texas to be as

small as 5/8 square mile (1.0 km2). Another study showed

that individual bobcats in southeastern Idaho maintain

home ranges from 2.5 square miles to 42.5 square miles

(6.5 km2 to 108 km2) during a year. Females and

yearlings with newly established territories tend to

have smaller and more exclusive ranges than males.

Females also tend to use all parts of their range more

intensively than adult males.

Bobcats commonly move 1 to

4 miles (2 to 7 km2) each day. One study found that

bobcats in Wyoming moved from 3 to 7.5 miles (5 to 12

km) each day. Transient animals can move much greater

distances; for example, a juvenile in one study moved 99

miles (158 km). Adult bobcats are usually found

separately except during the breeding season. Kittens

may be seen with their mothers in late summer through

winter. An Idaho study found adult bobcats and kittens

in den sites during periods of extreme cold and snow.

Females with kittens less than 4 months old generally

avoid adult males because they kill kittens.

In Canada and the western

United States, bobcat population levels tend to follow

prey densities. Some biologists believe that coyote

predation restricts bobcat numbers. Unfortunately, not

enough is known about the relative importance of factors

such as litter size, kitten survival, adult sex ratios,

and survival rates to predict changes in local bobcat

populations. Also, relatively low densities and variable

trapping success hinder researchers from easily

predicting changes in populations.

Since the late 1970s,

state game agencies have been tagging bobcat pelts

harvested in their states. Information from these pelts

is being used to estimate bobcat population trends and

factors that contribute to those changes.

Damage and Damage Identification

Bobcats are opportunistic

predators, feeding on poultry, sheep, goats, house cats,

small dogs, exotic birds and game animals, and, rarely,

calves. Bobcats can easily kill domestic and wild

turkeys, usually by climbing into their night roosts. In

some areas, bobcats can prevent the successful

introduction and establishment of wild turkeys or can

deplete existing populations. Bobcats leave a variety of

sign. Bobcat tracks are about 2 to 3 inches (5 to 8 cm)

in diameter and resemble those of a large house cat.

Their walking stride length between tracks is about 7

inches (18 cm).

Carcasses of bobcat kills

are often distinguishable from those of cougar, coyote,

or fox. Bobcats leave claw marks on the backs or

shoulders of adult deer or antelope. On large carcasses,

bobcats usually open an area just behind the ribs and

begin feeding on the viscera. Sometimes feeding starts

at the neck, shoulders, or hindquarters. Bobcats and

cougar leave clean-cut edges of tissue or bone while

coyotes leave ragged edges where they feed. Bobcats bite

the skull, neck, or throat of small prey like lambs,

kids, or fawns, and leave claw marks on their sides,

back, and shoulders. A single bite to the throat, just

behind the victim’s jaws, leaves canine teeth marks 3/4

to 1 inch (2 to 2.5 cm) apart. Carcasses that are

rabbit-size or smaller may be entirely consumed at one

feeding. Bobcats may return several times to feed on

large carcasses.

Bobcats, like cougars,

often attempt to cover unconsumed remains of kills by

scratching leaves, dirt, or snow over them. Bobcats

reach out about 15 inches (38 cm) in raking up debris to

cover their kills, while cougars may reach out 24 inches

(61 cm). Bobcats also leave signs at den sites. Young

kittens attempt to cover their feces at their dens.

Females with young kittens may mark prominent points

around den sites with their feces. Adult bobcats leave

conspicuous feces along frequently traveled rocky ridges

or other trails. These are sometimes used as territorial

markings at boundaries.

Adult bobcats also mark

trails or cave entrances with urine. This is sprayed on

rocks, bushes, or snow banks. Bobcats may leave claw

marks at urine or feces scent posts by scraping with

their hind feet. These marks are 10 to 12 inches (25 to

30 cm) long by 1/2 inch (1.25 cm) wide. Bobcats also

occasionally squirt a pasty substance from their anal

glands to mark areas. The color of this substance is

white to light yellow in young bobcats but is darker in

older bobcats.

Legal Status

Among midwestern states,

the bobcat is protected in Iowa, Illinois, Indiana,

Ohio, and in most counties of Kentucky. It is managed as

a furbearer or game animal in the plains states. Western

states generally exempt depredating bobcats from

protected status. They can usually be killed by

landowners or their agent. In the more eastern states

and states where bobcats are totally protected, permits

are required from the state wildlife agency to destroy

bobcats. Consult with your state wildlife agency

regarding local regulations and restrictions.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Use woven-wire enclosures to discourage bobcats from

entering poultry and small animal pens at night. Bobcats

can climb, so wooden fence posts or structures that give

the bobcat footing may not be effective. Bobcats also

have the ability to jump fences 6 feet (1.8 m) or more

in height. Use woven wire overhead if necessary. Fences

are seldom totally effective except in very small

enclosures.

Cultural Methods

Bobcats prefer areas with sufficient brush, timber,

rocks, and other cover, and normally do not move far

from these areas. Keep brush cut or sprayed around

ranches and farmsteads to eliminate routes of connecting

vegetation from bobcat habitat to potential predation

sites.

Frightening

Use night lighting with white flashing lights, or

bright continuous lighting, to repel bobcats. You can

also use blaring music, barking dogs, or changes in

familiar structures to temporarily discourage bobcats.

Repellents, Fumigants,

and Toxicants

No chemical repellents, fumigants, or toxicants are

currently registered for bobcats. Commercial house cat

repellents might be effective in some very unusual

circumstances. A hindrance to development of toxicants

is the bobcat’s preference to feed on fresh kills.

Trapping

Bobcats are more easily trapped than are coyotes or

foxes, but the bobcat’s reclusiveness makes set

locations difficult to find. When hunting, bobcats use

their sense of smell less than coyotes do, so lures and

baits are usually not effective. The bobcat’s acute

vision, hearing, and inquisitiveness however, can be

capitalized upon. Even with the best sets, bobcats

cannot be lured from their course of travel more than a

few yards (m). The bobcat’s use of dense cover for

capturing rodents and rabbits can be used in capture

techniques to guide the animal or even its footsteps. In

the past, the demand for bobcat pelts was moderately

high due to fur values. This had encouraged late fall

and winter harvest periods. Also, the bobcat’s high fur

quality attracts harvest for recreation or utility. If

bobcat depredations are common over time, consider

inviting a fur trapper to take bobcats during prime fur

periods. Fewer bobcats may result in less competition

for native foods and less depredation. Fur trappers may

undertake the capture and relocation of bobcats during

spring and summer months from areas where depredations

are occurring in return for fur trapping rights during

fall and winter months. Many of the same sets used for

foxes and coyotes will also catch bobcats. Few sets that

target bobcats will catch other predators. Bobcats can

be led by guide sticks or brush to dirt hole or flat

sets where proper lures are used.

Leghold

Traps. Steel leghold traps, Nos. 2, 3, and 4 are

commonly used to capture bobcats. Trap size selection

depends on the area and weather conditions. For

coarse-textured sandy soils, use a No. 2 coilspring

trap. Use a No. 3 trap for wet or fine-textured clay

soils. Use No. 4 traps for frozen soils or in deep snow

sets. A bobcat is easy to hold, but sometimes more power

and jaw spread is required than a No. 2 coilspring

provides. The bobcat’s foot may be too large for proper

foot placement and a good catch. Guide sticks and stones

can be used (Fig. 3). Leghold

Traps. Steel leghold traps, Nos. 2, 3, and 4 are

commonly used to capture bobcats. Trap size selection

depends on the area and weather conditions. For

coarse-textured sandy soils, use a No. 2 coilspring

trap. Use a No. 3 trap for wet or fine-textured clay

soils. Use No. 4 traps for frozen soils or in deep snow

sets. A bobcat is easy to hold, but sometimes more power

and jaw spread is required than a No. 2 coilspring

provides. The bobcat’s foot may be too large for proper

foot placement and a good catch. Guide sticks and stones

can be used (Fig. 3).

Bobcats prefer fresh baits

such as rabbit, muskrat, or poultry. Scattered bits of

fur and feathers work well. Bobcats can be drawn to

traps by “flags” hung from trees or rocks located near

trap sets (Fig. 4). Suspend flags about 4 feet (1.3 m)

above the

ground

with fine wire or string. A combination of stiff wire

with string attached to its end prevents entangling in

tree branches. Where animal parts are illegal, aluminum

foil or jar lids or imitation fur can be used. Location

is the key to trapping bobcats. If the location is not

correct, no flags or baits will work. A flag set uses a

piece of fur or a couple of feathers suspended about 4

feet (120 cm) above ground with fine wire or string.

Build a small mound of soil under the flag 1 foot (30

cm) high and 2 feet (60 cm) in diameter. Bobcats step

onto these mounds to reach the flag. Bury steel leghold

traps in the Fig. 3. Blind or trail set using guide

sticks and stones. Bobcat trail Stones Pebbles (Traps

bedded in ground) C-39 Fig. 5. Trash or scat mound set.

mound. Steel leghold traps can also be used in other

sets. See instructions in the Mountain Lions chapter.

Trash or mound sets take advantage of bobcats covering

their scat and leftover food (Fig. 5). This set is very

common. Pull up a pile of trash or litter over a large

bait, to mimic bobcat behavior. A smaller mound can be

made with urine poured over the trash. These sets are

useful where exposed baits are illegal. Both sets should

be used where backing such as rocks or trees are

available. Place a steel leghold trap and guide sticks

in front of trash pile sets. ground

with fine wire or string. A combination of stiff wire

with string attached to its end prevents entangling in

tree branches. Where animal parts are illegal, aluminum

foil or jar lids or imitation fur can be used. Location

is the key to trapping bobcats. If the location is not

correct, no flags or baits will work. A flag set uses a

piece of fur or a couple of feathers suspended about 4

feet (120 cm) above ground with fine wire or string.

Build a small mound of soil under the flag 1 foot (30

cm) high and 2 feet (60 cm) in diameter. Bobcats step

onto these mounds to reach the flag. Bury steel leghold

traps in the Fig. 3. Blind or trail set using guide

sticks and stones. Bobcat trail Stones Pebbles (Traps

bedded in ground) C-39 Fig. 5. Trash or scat mound set.

mound. Steel leghold traps can also be used in other

sets. See instructions in the Mountain Lions chapter.

Trash or mound sets take advantage of bobcats covering

their scat and leftover food (Fig. 5). This set is very

common. Pull up a pile of trash or litter over a large

bait, to mimic bobcat behavior. A smaller mound can be

made with urine poured over the trash. These sets are

useful where exposed baits are illegal. Both sets should

be used where backing such as rocks or trees are

available. Place a steel leghold trap and guide sticks

in front of trash pile sets.

Body-gripping Traps.

Bodygripping traps are very effective killer traps for

eliminating bobcats. These kill traps are spring-loaded.

When the trigger is released, the trap closes on the

animal in a scissors-like action. An example of this

type of trap is the Victor ® No. 330 Conibear®. This

trap, and others like it, can be very dangerous to use,

breaking arms, or killing large dogs if improperly set.

Check local regulations to determine if they are legal

to use in your area. For bobcats, set these traps in

trails at the base of a cliff or in brush. Use bait or

lures beyond the trap to entice the bobcat to walk

through it. Strategic bait placement also keeps bobcats

preoccupied. These sets can be made in dense cover in

trails, at the entrances to dens, or at gaps in fences

or brush where bobcats travel. These traps can also be

set in entrances to cubbies constructed to trap bobcats.

Place an attractive bait at the rear of the cubby and

place the kill trap so that the bobcat must go through

it to reach the bait. See Mountain Lions for other sets

made with body-gripping traps. Specific instructions on

trapping bobcats are found in Boddicker (1980).

Extensive bobcat trapping methods can also be found in

Weiland (1976), Young (1941), Johnson (1979), and

Musgrave and Blair (1979). Check all local and state

laws for using traps, snares, baits, or lures.

Wire Cage Traps.

Wire Cage Traps. Very large cage traps, made of wire

mesh or metal, when properly set, are effective.

Commercial traps from 15 x 15 x 40 inches (38 x 38 x 100

cm) up to 24 x 24 x 48 inches (60 x 60 x 120 cm) are

available. See the Supplies and Materials chapter. Use

brush or grass on the top and sides of the cage to give

the appearance of a natural “cubby” or recess in a rock

outcrop or brush. Traps should be set in the vicinity of

depredations, travelways to and from bobcat cover,

hunting sites. Cover the cage bottom with soil. Bait the

cage with poultry, rabbit, or muskrat carcasses, or live

animals. Check local and state laws for restrictions.

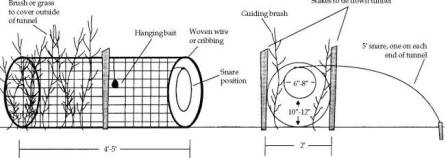

Snares. Snares are

very effective for bobcats but require expertise and

caution. When properly set, a snare can be used to

either kill or restrain a bobcat. Snares can be placed

in the same locations and situations as body-gripping

traps. They are particularly effective in cubby sets,

bobcat runways, and den entrances (Fig. 6). Properly

placed, snares offer the advantages of bodygripping

traps without the danger to pets and non-target

wildlife.

Fig.

6 Cubby set with snare Fig.

6 Cubby set with snare

Fig.7.

Trail set with snare Fig.7.

Trail set with snare

Set snares in trails where

bobcats are known to travel (Fig. 7). Baits and lures

are usually not used with snares and may hinder success.

Use camouflage only to break up some of the outline of

the snare, preferably with native material, like

grasses. Do not tie camouflage material to the loop of

the snare. Spring-loaded snares work best. Put “memory”

into the snare by placing tension on the inside of the

lock against the cable with your finger as you close the

snare once or twice. This prevents a bobcat from walking

through a snare. Cables respond to the memory by closing

easily.

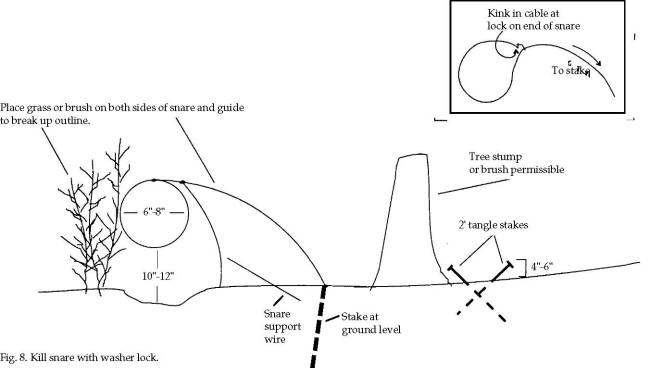

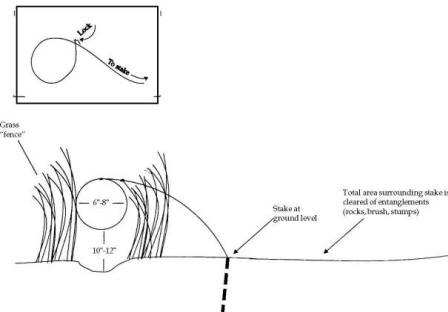

Kill snares actually kill

the captured bobcat and are most often used during the

furbearer season or for animals for which relocation has

failed (Fig. 8). They are best made from fine steel

cable, 1/16 inch (0.15 cm) or 5/64 inch (0.2 cm) in

diameter. Positive locks work well. Set kill snares with

the bottom of the loop about 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30

cm) off the ground with a loop 6 to 8 inches (15 to 20

cm) in diameter. This loop must be set perpendicular to

the trail.

Live snare sets capture and hold bobcats alive. They

differ from kill snare sets by their cable size, locks,

and entanglement precautions. Larger cables and relaxed

locks on live snare sets can reduce injury if set

properly. Relaxed locks tighten onto animals but relax

as the animal stops struggling. This allows the animal

to breath normally and regain composure.

Kill snares may be tied

off to a 3-inch (7.5-cm) diameter tree or larger . To

aid quick kills, hammer 2-foot (60-cm) stakes into the

ground, leaving 6 to 8 inches (15 to 20 cm) aboveground.

Killsnare locks (Gregerson, Camlock, Thompson, Keflock)

are in several of the supply catalogs listed in Supplies

and Materials.

The live snare set (Fig. 9 at left) requires more

expertise than the kill snare set. Also, capture and

transport of bobcats is very dangerous. Use 3/32-inch

(0.25-cm) steel cable 6 to 8 feet (1.9 to 2.5 m) long.

Use snares with high quality swivels located midway or

closer to the loop. Stake live snares to the ground with

steel stakes, hammered to just below ground level. Use

loop sizes as in the kill snare set. Clear brush and

other entanglements from the area.

Use extreme caution when

releasing a snared animal. Catch poles with adjustable

steel nooses, thick leather gloves or gauntlets, and

other protective clothing are necessary. Immobilizing

drugs such as ketamine hydrochloride should be

accessible. Two people should handle captures; one at

the neck and the other at the back feet to remove the

snare. Cut a 1/2- x 4-inch (1.2- x 10-cm) slot from the

bottom up toward the center of a 3- x 3-foot (1- x 1-m),

5/8-inch (1.6-cm) or larger piece of plywood. A handle

should be attached at the upper end. Place the plywood

between you and the snared animal and let the cable run

through the slot as you approach, keeping the cable

tight. Check live snare sets frequently to avoid

unnecessary stress and loss of captured bobcats to

predators, such as eagles, coyotes, and mountain lions.

See Supplies and Materials for suppliers of bobcat

snares. Always ask for expert advice before attempting

live captures. Extensive instructions on snaring can be

found in Grawe (1981) and Krause (1981).

Shooting

Bobcats respond to predator calls at night and can

be shot. Use a red, blue, or amber lens with an 80,000-

to 200,000-candlepower (lumen) spotlight to locate

bobcats. Sources of predator calls are found in Supplies

and Materials. Dogs trained to track bobcats can be

useful in removing problem animals. Bobcats can be shot

after being treed. Bobcats may develop a time pattern in

their depredations on livestock or poultry. You can lie

in wait and ambush the bobcat as it comes in for the

kill. Rifles of .22 centerfire or larger, or shotguns

with 1 1/4 ounces (35 g) or more of No. 2 or larger shot

are recommended, since bobcats are rather large and

require considerable killing power.

Economics of Damage and Control

Damage by bobcats is

rather uncommon and statistics related to this damage

are not well developed. In western states where data

have been obtained, losses of sheep and goats have

comprised less than 10% of all predation losses. Typical

complaints of bobcat predation involve house cats and

poultry allowed to roam at will in mountain subdivisions

and ranches. Bobcats are taken by trappers and by

hunters using hounds. The pelts are used for coats,

trim, and accessories, the spotted belly fur being most

valuable. Bobcat pelts are used for wall decorations and

rugs. In recent years, North American bobcat harvests

have produced about 25,000 pelts valued at $2.5 million

annually. Aesthetically, the bobcat is a highly regarded

carnivore. To many people the bobcat represents the

essence of wildness in any habitat it occupies.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Major

Boddicker, who authored this chapter in the 1983 edition

of this manual. The sections on identification, habitat,

food habits, general biology, and economics were adapted

from his work. Thanks also go to Bill Phillips, Arizona

Game and Fish Department, and Chuck McCullough, Nebraska

Game and Parks Commission, for their information. Figure

1 from Schwartz and Schwartz (1981). Figure 2 by Sheri

Bordeaux. Figures 3 through 6, 8 and 9 by Denny Hogeland,

adapted by Sheri Bordeaux. Figure 7 adapted from M. L.

Boddicker, 1980.

For

Additional Information

Bailey, T. N. 1974. Social

organization in a bobcat population. J. Wildl. Manage.

38:435-446.

Bailey, T. N. 1980.

Factors of bobcat social organization and some

management implications. Proc. Worldwide Furbearer Conf.

2:984-1000.

Blair, C. 1981. Predator

caller’s companion. Winchester Press, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

267 pp.

Blum, L. G., and P. C.

Escherich. 1979. Bobcat research conference proceedings,

current research on biology and management of Lynx rufus.

Natl. Wildl. Fed. Sci. Tech. Ser. 6 137 pp.

Boddicker, M. L., (ed.).

1980. Managing Rocky Mountain furbearers. Colorado

Trappers Assoc. LaPorte, Colorado. 176 pp.

Clark, T. W., and M. R.

Stromberg. 1987. Mammals in Wyoming. Univ. Kansas Museum

Nat. Hist. 319 pp.

Crowe, D. M. 1972. The

presence of annuli in bobcat tooth cementum layers. J.

Wildl. Manage. 36:1330-1332.

Crowe, D. M. 1975a. A

model for exploited bobcat populations in Wyoming. J.

Wildl. Manage. 39:408-415.

Crowe, D. M. 1975b.

Aspects of aging, growth, and reproduction of bobcats

from Wyoming. J. Mammal. 56:177-198.

Deems, E. F., and D.

Pursley, (eds.). 1983. North American furbearers — a

contemporary reference. Int. Assoc. Fish Wildl. Agencies

and Maryland Dep. Nat. Resour., Annapolis. 223 pp.

Fredrickson L. 1981.

Bobcat management. South Dakota Conserv. Digest

48:10-13.

Gluesing, E. A., S. D.

Miller, and R. M. Mitchell. 1986. Management of the

North American bobcat: information needs for

nondetrimental findings. Trans. N. A. Wildl. Nat. Resour.

Conf. 51:183-192.

Grawe, A. 1981. Grawe’s

snaring methods. Wahpeton, North Dakota. 48 pp.

Johnson, C. 1979. The

bobcat trappers bible. Spearman Publ. Sutton, Nebraska.

32 pp.

Karpowitz, J. F., and J.

T. Flinders. 1979. Bobcat research in Utah—a progress

report. Natl. Wildl. Fed. Sci. Tech. Ser. 6:70-73

Koehler, G. 1987. The

bobcat. Pages 399-409 in R. L. De Silvestro, ed. Audubon

Wildlife Report 1987. Natl. Audubon Soc., New York.

Krause, T. 1981. Dynamite

snares and snaring. Spearman Pub., Sutton, Nebraska. 80

pp.

McCord, C. M., and L. E.

Cardoza. 1982. Bobcat and lynx. Pages 728-768 in J. A.

Chapman and G. A. Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North

America: biology, management, and economics. The Johns

Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore, Maryland. Musgrave, B.,

and C. Blair. 1979. Fur trapping. Winchester Press,

Tulsa, Oklahoma. 246 pp.

Robinson, W. B. 1953.

Population trends of predators and fur animals in 1080

station areas. J. Mammal. 34:220-227.

Rue, L. 1981. Furbearing

animals of North America. Crown Pub., New York. 343 pp.

Sampson, F. W. 1967.

Missouri bobcats. Missouri Conserv. 28:7.

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri, rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp.

Scott, J. 1977. On the

track of the lynx. Colorado Outdoors 26:1-3.

Wassmer, D. A., D. D.

Guenther, and J. N. Layn. 1988. Ecology of the bobcat in

south-central Florida. Bulls. Florida St. Museum, Biol.

Sci. 33:159-228.

Weiland, G. 1976. Long

liner cat trapping. Garold Weiland, Pub. Glenham, South

Dakota. 25 pp.

Young, S. P. 1941. Hints

on bobcat trapping. US Fish Wildl. Serv. Circ. No. 1, US

Govt. Print. Off., Washington, DC. 6 pp.

Young, S. P. 1958. The

bobcat of North America. Stackpole Co., Harrisburg,

Pennsylvania. 193 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994 Cooperative Extension Division

Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska - Lincoln United States

Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health

Inspection Service Animal Damage Control Great Plains

Agricultural Council Wildlife Committee

01/12/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|