|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: Black Bears |

|

|

Figure 1. Black bear (Ursus

americanus)

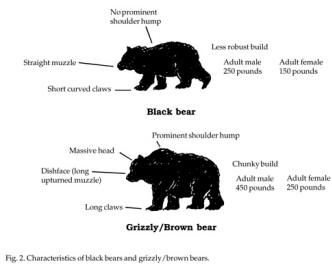

Identification

The black bear (Ursus

americanus, Fig. 1) is the smallest and most widely

distributed of the North American bears.

Adults typically weigh 100 to 400 pounds (45 to 182 kg)

and measure from 4 to 6 feet (120 to 180 cm) long. Some

adult males attain weights of over 600 pounds (270 kg).

They are massive and strongly built animals. Black bears

east of the Mississippi are predominantly black, but in

the Rocky Mountains and westward various shades of

brown, cinnamon, and even blond are common. The head is

moderately sized with a straight profile and tapering

nose. The ears are relatively small, rounded, and erect.

The tail is short (3 to 6 inches [8 to 15 cm]) and

inconspicuous. Each foot has five curved claws about 1

inch (2.5 cm) long that are non-retractable. Bears walk

with a shuffling gait, but can be quite agile and quick

when necessary. For short distances, they can run up to

35 miles per hour (56 km/hr). They are quite adept at

climbing trees and are good swimmers. It is important to

be able to distinguish between black bears and grizzly/

brown bears (Ursus arctos). The grizzly/brown bear is

typically much larger than the black bear, ranging from

400 to 1,300 pounds (180 to 585 kg). Its guard hairs

have whitish or silvery tips, giving it a frosted or

“grizzly” appearance. Grizzly/brown bears have a

pronounced hump over the shoulder; a shortened, often

dished face; relatively small ears; and long claws (Fig.

2). bears.

Adults typically weigh 100 to 400 pounds (45 to 182 kg)

and measure from 4 to 6 feet (120 to 180 cm) long. Some

adult males attain weights of over 600 pounds (270 kg).

They are massive and strongly built animals. Black bears

east of the Mississippi are predominantly black, but in

the Rocky Mountains and westward various shades of

brown, cinnamon, and even blond are common. The head is

moderately sized with a straight profile and tapering

nose. The ears are relatively small, rounded, and erect.

The tail is short (3 to 6 inches [8 to 15 cm]) and

inconspicuous. Each foot has five curved claws about 1

inch (2.5 cm) long that are non-retractable. Bears walk

with a shuffling gait, but can be quite agile and quick

when necessary. For short distances, they can run up to

35 miles per hour (56 km/hr). They are quite adept at

climbing trees and are good swimmers. It is important to

be able to distinguish between black bears and grizzly/

brown bears (Ursus arctos). The grizzly/brown bear is

typically much larger than the black bear, ranging from

400 to 1,300 pounds (180 to 585 kg). Its guard hairs

have whitish or silvery tips, giving it a frosted or

“grizzly” appearance. Grizzly/brown bears have a

pronounced hump over the shoulder; a shortened, often

dished face; relatively small ears; and long claws (Fig.

2).

Range Range

Black bears historically

ranged throughout most of North America except for the

desert southwest and the treeless barrens of northern

Canada. They still occupy much of their original range

with the exception of the Great Plains, the midwestern

states, and parts of the eastern and southern coastal

states (Fig. 3). Black bear and grizzly/brown bear

distributions overlap in the Rocky Mountains, Western

Canada, and Alaska.

Habitat

Black bears frequent

heavily forested areas, including large swamps and

mountainous regions. Mixed hardwood forests interspersed

with streams and swamps are typical habitats. Highest

growth rates are achieved in eastern deciduous forests

where there is an abundance and variety of foods. Black

bears depend on forests for their seasonal and yearly

requirements of food, water, cover, and space.

Food Habits

Black bears are

omnivorous, foraging on a wide variety of plants and

animals. Their diet is typically determined by the

seasonal availability of food. Typical foods include

grasses, berries, nuts, tubers, wood fiber, insects,

small mammals, eggs, carrion, and garbage. Food

shortages occur occasionally in northern bear ranges

when summer and fall mast crops (berries and nuts) fail.

During such years, bears become bolder and travel more

widely in their search for food. Human encounters with

bears are more frequent during such years, as are

complaints of crop damage and livestock losses. Fig. 3.

Range of the black bear in North America.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Black bears typically are

nocturnal, although occasionally they are active during

the day. In the South, black bears tend to be active

year-round; but in northern areas, black bears undergo a

period of semihibernation during winter. Bears spend

this period of dormancy in dens, such as hollow logs,

windfalls, brush piles, caves, and holes dug into the

ground. Bears in northern areas may remain in their dens

for 5 to 7 months, foregoing food, water, and

elimination. Most cubs are born between late December

and early February, while the female is still denning.

Black bears breed during the summer months, usually in

late June or early July. Males travel extensively in

search of receptive females. Both sexes are promiscuous.

Fighting occurs between rival males as well as between

males and unreceptive females. Dominant females may

suppress the breeding activities of subordinate females.

After mating, the fertilized egg does not implant

immediately, but remains unattached in the uterus until

fall. Females in good condition will usually produce 2

or 3 cubs that weigh 7 to 12 ounces (198 to 340 g) at

birth.

After giving birth, the

sow may continue her winter sleep while the cubs are

awake and nursing. Lactating females do not come into

estrus, so females generally breed only every other

year. Parental care is solely the female’s

responsibility. Males will kill and eat cubs if they

have the opportunity. Cubs are weaned in late summer but

usually remain close to the female throughout their

first year. This social unit breaks up when the female

comes into her next estrus. After the breeding season,

the female and her yearlings may travel together for a

few weeks. Black bears become sexually mature at

approximately 3 1/2 years of age, but some females may

not breed until their fourth year or later.

In North America, black

bear densities range from 0.3 to 3.4 bears per square

mile (0.1 to 1.3 bears/km2). Densities are highest in

the Pacific Northwest because of the high diversity of

habitats and long foraging season. The home range of

black bears is dependent on the type and quality of the

habitat and the sex and age of the bear. In mountainous

regions, bears encounter a variety of habitats by moving

up or down in elevation. Where the terrain is flatter,

bears typically range more widely in search of food,

water, cover, and space. Most adult females have

well-defined home ranges that vary from 6 to 19 square

miles (15 to 50 km2).Ranges of adult males are usually

several times larger.

Black bears are powerful

animals that have few natural enemies. Despite their

strength and dominant position, they are remarkably

tolerant of humans. Interactions between people and

black bears are usually benign. When surprised or

protecting cubs, a black bear will threaten the intruder

by laying back its ears, uttering a series of huffs,

chopping its jaws, and stamping its feet. This may be

followed by a charge, but in most instances it is only a

bluff, as the bear will advance only a few yards (m)

before stopping. There are very few cases where a black

bear has charged and attacked a human. Usually people

are unaware that bears are even in the vicinity. Most

bears will avoid people, except bears that have learned

to associate food with people. Food conditioning occurs

most often at garbage dumps, campgrounds, and sites

where people regularly feed bears. Habituated,

food-conditioned bears pose the greatest threat to

humans (Herrero 1985, Kolenosky and Strathearn 1987).

Damage and Damage Identification

Damage caused by black

bears is quite diverse, ranging from trampling sweet

corn fields and tearing up turf to destroying beehives

and even (rarely) killing humans. Black bears are noted

for nuisance problems such as scavenging in garbage

cans, breaking in and demolishing the interiors of

cabins, and raiding camper’s campsites and food caches.

Bears also become a nuisance when they forage in garbage

dumps and landfills. Black bears are about the only

animals, besides skunks, that molest beehives. Evidence

of bear damage includes broken and scattered combs and

hives showing claw and tooth marks. Hair, tracks, scats,

and other sign may be found in the immediate area. A

bear will usually use the same path to return every

night until all of the brood, comb, and honey are eaten.

Field crops such as corn

and oats are also damaged occasionally by hungry black

bears. Large, localized areas of broken, smashed stalks

show where bears have fed in cornfields. Bears eat the

entire cob, whereas raccoons strip the ears from the

stalks and chew the kernels from the ears. Black bears

prefer corn in the milk stage.

Bears can cause extensive

damage to trees, especially in second-growth forests, by

feeding on the inner bark or by clawing off the bark to

leave territorial markings. Black bears damage orchards

by breaking down trees and branches in their attempts to

reach fruit. They will often return to an orchard

nightly once feeding starts. Due to the perennial nature

of orchard damage, losses can be economically

significant.

Few black bears learn to

kill livestock, but the behavior, once developed,

usually persists. The severity of black bear predation

makes solving the problem very important to the

individuals who suffer the losses. If bears are suspect,

look for deep tooth marks (about 1/2 inch [1.3 cm] in

diameter) on the neck directly behind the ears. On large

animals, look for large claw marks (1/2 inch [1.3 cm]

between individual marks) on the shoulders and sides.

Bear predation must be

distinguished from coyote or dog attacks. Coyotes

typically attack the throat region. Dogs chase their

prey, often slashing the hind legs and mutilating the

animal. Tooth marks on the back of the neck are not

usually found on coyote and dog kills. Claw marks are

less prominent on coyote or dog kills, if present at

all.

Different types of

livestock behave differently when attacked by bears.

Sheep tend to bunch up when approached. Often three or

more will be killed in a small area. Cattle have a

tendency to scatter when a bear approaches. Kills

usually consist of single animals. Hogs can evade bears

in the open and are more often killed when confined.

Horses are rarely killed by bears, but they do get

clawed on the sides.

After an animal is killed,

black bears will typically open the body cavity and

remove the internal organs. The liver and other vital

organs are eaten first, followed by the hindquarters.

Udders of lactating females are also preferred. When a

bear makes a kill, it usually returns to the site at

dusk. Bears prefer to feed alone. If an animal is killed

in the open, the bear may drag it into the woods or

brush and cover the remains with leaves, grass, soil,

and forest debris. The bear will periodically return to

this cache site to feed on the decomposing carcass.

Black bears occasionally

threaten human health and safety. Dr. Stephen Herrero

documented 500 injuries to humans resulting from

encounters with black bears from 1960 to 1980 (Herrero

1985). Of these, 90% were minor injuries (minor bites,

scratches, and bruises). Only 23 fatalities due to black

bear attacks were recorded from 1900 to 1980. These are

remarkably low numbers, considering the geographic

overlap of human and black bear populations. Ninety

percent of all incidents were likely associated with

habituated, food-conditioned bears.

Legal Status

In the early 1900s, black

bears were classified as nuisance or pest species

because of agricultural depredations. Times have changed

and bear distributions and populations have diminished

because of human activity. Many states, such as

Colorado, Idaho, Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon,

Utah, and Wisconsin, manage the black bear as a big game

animal. Most other states either consider black bears as

not present or completely protect the species. In most

western states, livestock owners and property owners may

legally kill bears that are killing livestock, damaging

property, or threatening human safety. Several states

require a permit before removing a bear when the damage

situation is not acute. In states where complete

protection is required, the state wildlife agency or

USDA-APHIS-ADC will usually offer prompt service when a

problem occurs. The problem bear will be livetrapped and

moved, killed, and/or compensation for damage offered.

In a life-threatening situation, the bear can be shot,

but proof of jeopardy may be required to avoid a

citation for illegal killing.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Fencing has proven effective in deterring bears from

landfills, apiaries, cabins, and other high-value

properties. Fencing, however, is a relatively expensive

abatement measure. Consider the extent, duration, and

expense of damage when developing a prevention program.

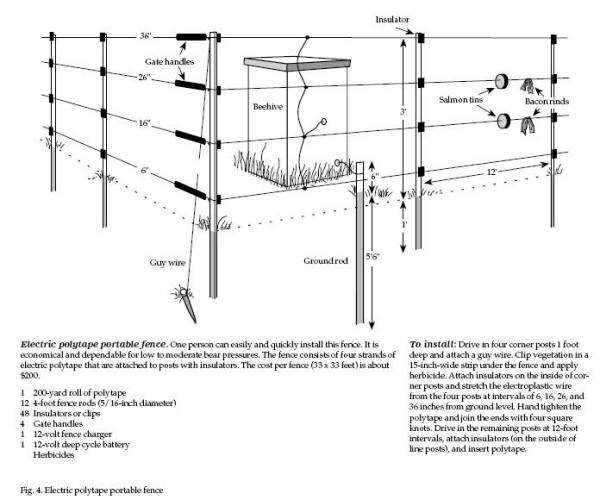

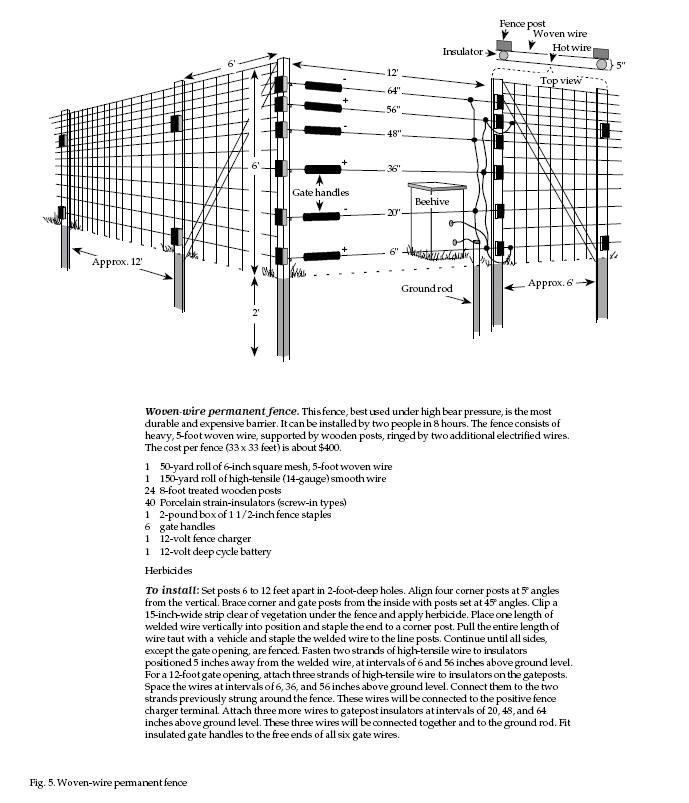

Numerous fence designs

have been used with varying degrees of success. Electric

fence chargers increase effectiveness. Depending on the

amount of bear pressure, use an electric polytape

portable fence (Fig. 4), or a welded-wire permanent

fence (Fig. 5).

Fence Energizing System

and Maintenance. To energize the fences, use a

110-volt outlet or 12-volt deep cell (marine) battery

connected to a high-output fence charger. Place the

fence charger and battery in a case or empty beehive to

protect them against weather and theft. Drive a ground

rod 5 to 7 feet (1.5 to 2.1 m) into the ground,

preferably into moist soil. Connect the ground terminal

of the charger to the ground rod with a wire and ground

clamp. Connect the positive fence terminal to the fence

with a short piece of fence wire. Use connectors to

ensure good contact. Electric fences must deliver an

effective shock to repel bears. Bears can be lured into

licking or sniffing the wire by attaching attractants

(salmon or tuna tins and bacon rinds) to the fence.

Grounding may be increased, especially in dry, sandy

soil, by laying grounded chicken wire around the outside

perimeter of the electric fence.

Check the fence voltage

each week at a distance from the fence charger; it

should yield at least 3,000 volts. To protect against

voltage loss, keep the battery and fence charger dry and

their connections free of corrosion. Make certain all

connections are secure and check for faulty insulators

(arcing between wire and post). Also clip vegetation

beneath the fence. Each month, check the fence tension

and replace baits with new salmon tins and bacon rinds.

Always recharge the batteries during the day so that the

fence is energized at night.

Black bears are strong

enough to tear open doors, rip holes in siding, and

break glass windows to gain access to food stored inside

cabins, tents, and other structures. Use solid frame

construction, 3/4-inch (2-cm) plywood sheeting, and

strong, tight-fitting shutters and doors. Steel plating

is more impervious than wood.

Bear-proof containers are

available for campers in a variety of sizes. They can be

used to safely store food and other bear attractants

during backpacking trips or other outdoor excursions. In

the absence of bear-proof containers, store food in

airtight containers and suspend them by rope between two

tall trees that are at least 100 yards (100 m) downwind

of your campsite.

Food, supplies, and

beehives can be stored 15 to 20 feet (4 to 6 m) above

ground on elevated platforms or bear poles. Support

poles should be at least 6 inches (15 cm) in diameter

and wrapped with a 4-foot-wide (1.4-m) piece of

galvanized sheet metal, 6 to 7 feet (2 m) above ground.

You can also place one or two hives on a flat or

low-sloping garage roof. Be sure to add extra roof

braces because two hives full of honey can weigh 800

pounds (360 kg) or more. An innovative technique for

beekeepers is to place hives on a fenced (three-strand

electric) flatbed trailer (8 feet x 40 feet [2.4 m x

12.2 m]). Though expensive, this method makes hives less

vulnerable to bear damage and makes moving them very

easy.

Cultural Methods

Prevention is the best method of controlling black

bear damage. Sanitation and proper solid waste

management are key considerations. Store food, organic

wastes, and other bear attractants in bear-proof

containers. Use garbage cans for nonfood items only.

Implement regular garbage pickup and practice

incineration. Reduce access to landfills through

fencing, and bury refuse daily. Eliminate garbage dumps.

Place livestock pens and

beehives at least 50 yards (50 m) away from wooded areas

and protective cover. Confine livestock in buildings and

pens, especially during lambing or calving seasons.

Remove carcasses from the site and dispose of them by

rendering or deep burial.

Plant susceptible crops

(corn, oats, fruit) away from areas of protective cover.

Pick and remove all fruit from orchard trees. Remove

protective cover from a radius of 50 yards (50 m) around

occupied buildings and residences. Locate campgrounds,

campsites, and hiking trails in areas that are not

frequented by bears to minimize people/bear encounters.

Avoid seasonal feeding and denning areas and frequently

used game trails. Where possible, clear hiking trails to

provide a minimum viewing distance of 50 yards (50 m)

down the trail.

Frightening Devices and

Deterrents

Black bears can be frightened from an area (such as

buildings, livestock corrals, orchards) by the extended

use of night lights, strobe lights, loud music,

pyrotechnics, exploder canons, scarecrows, and trained

guard dogs. The position of such frightening devices

should be changed frequently. Over a period of time,

animals usually become used to scare devices. Bears

often become tolerant of human activity, too. At this

point, scare devices are ineffective and human safety

becomes a concern.

Black bears are

occasionally encountered in the backcountry on trails or

at campsites. They can usually be frightened away by

shouting, clapping hands, throwing objects, and by

chasing. Such actions can be augmented by the noise of

pots banging, gunfire, cracker shells, gas-propelled

boat horns, and engines revving. It is important to

attempt to determine the motivation of the offending

bears. Habituated, food-conditioned bears can be very

dangerous. Aggressive behavior toward a black bear

should not be carried so far as to threaten the bear and

elicit an attack.

Black bears can be

deterred from landfills, occupied buildings, and other

sites by the use of 12-gauge plastic slugs or 38-mm

rubber bullets. Aim for the large muscle mass in the

hind quarters. Avoid the neck and front shoulders to

minimize the risk of hitting and damaging an eye.

Firearm safety training is recommended.

Repellents

Capsaicin or concentrated red pepper spray has been

tested and used effectively on black bears. The spray

range on most products is less than 30 feet (10 m), so

capsaicin is only effective in close encounters.

Capsaicin spray may become more popular where use of

firearms is limited.

Toxicants None are

registered.

Fumigants None are

registered.

Trapping

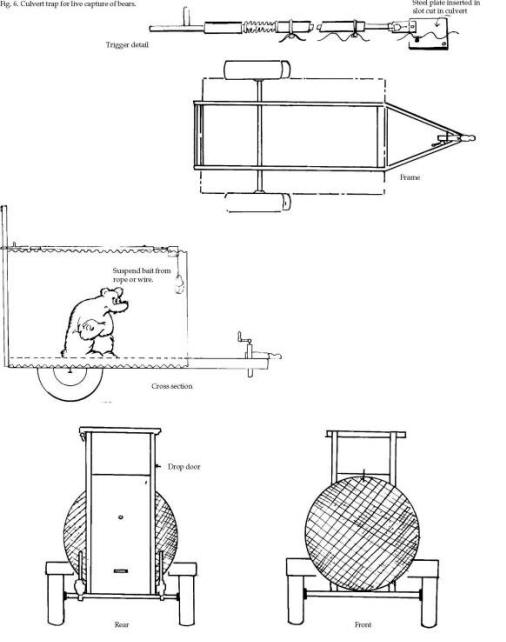

Culvert and Barrel Traps. Live trapping black

bears in culvert or barrel traps is highly effective and

convenient (Fig. 6). Set one or two culvert traps in the

area where the bear is causing a problem. Post warning

signs on and in the vicinity of the trap. Use baits to

lure the bear into the trap. Successful baits include

decaying fish, beaver carcasses, livestock offal, fruit,

candy, molasses, and honey. When the trap door falls,

the bear is safely held without a need for dangerous

handling or transfer. Bears can be immobilized, released

at another site, or destroyed if necessary. Trapped

bears that are released should first be transported at

least 50 miles (80 km), preferably across a substantial

geographic barrier such as a large river, swamp, or

mountain range, and released in a remote area. Remote

release mechanisms are highly recommended. Occasionally,

food-conditioned bears will repeat their offenses. A

problem bear should be released only once. If it causes

subsequent problems it should be destroyed.

Foot Snares.

The Aldrich-type foot snare (Fig. 7) is used extensively

by USDA-APHIS-ADC and state wildlife agency personnel to

catch problem bears. This method is safe, when correctly

used, and allows for the release of nontarget animals.

Bears captured in this manner can be tranquilized,

released, translocated, or destroyed. Use baits as

described previously to attract bears to foot snare

sets.

The tools required for the

pipe set are an Aldrich foot snare complete with the

spring throw arm, a 9-inch (23-cm) long, 5-inch (13-cm)

diameter piece of stove pipe, iron pin, hammer, and

shovel. Cut a 1-inch (2.5-cm) slot, 6 1/2 inches (16.5

cm) long, down one side of the pipe. Place the pipe in a

hole dug 9 inches (23 cm) deep into the ground. Cut a

groove in the ground to accommodate the spring throw arm

so that the pan will extend through the slot into the

center of the pipe. The top of the pipe should be level

with the ground surface. Anchor the pipe securely to the

ground, where possible, by attaching it to spikes or a

stake driven into the ground inside the can. Bears will

try to pull the pipe out of the ground if it “gives.”

The spring throw arm should be placed with the pan

extending into the pipe slot 6 inches (15 cm) down from

the top of the pipe. Pack soil around the pipe 1 inch

(2.5 cm) from the top. Leave the pipe slot open and the

spring uncovered. Loop the cable around the pipe,

leaving 1/2 inch (1.3 cm) of slack. Place the cable over

the hood on the spring throw arm, then spike the cable

to the ground in back of the throw arm. The cable is

spiked to keep it flush to the ground so that it will

not unkink or spring up prematurely. Cover the cable

loop with soil to the top of the pipe. Anchor the cable

securely to a tree at least 8 inches (20 cm) in

diameter. Cover the spring throw arm and pipe slot with

grass and leaves. Place a few boughs and some brush

around the set to direct the bear into the pipe. The

slot in the pipe and the spring throw arm should be at

the back of the set. The bear can approach the set from

either side or the front. Melt bacon into the bottom of

the pipe and drop a small piece in. The bacon should not

lie on the pan. Other bait or scent, such as a

fish-scented rag, may be used. Place a 15 to 20-pound

(6.8- to 9-kg) rock over the top of the pipe. Melt bacon

grease on the top of it or rub it on. The rock will

serve to prevent humans, birds, nontarget wild animals,

and livestock from being caught in the snare.

The bear will approach the

set and proceed to lick the grease off the rock. It will

then roll the rock from the top of the pipe and try to

reach the bait with its mouth. When this fails, it will

use a front foot, which will then be caught in the

snare. The bear will try to reach the bait first with

its mouth and may spring the set if the pan is not

placed the required 6 inches (15 cm) below the top of

the pipe. Pipe sets are more efficient, more economical,

and safer than leghold traps.

Shooting

Shooting is effective, but often a last resort, in

dealing with a problem black bear. Permits are required

in most states and provinces to shoot a bear out of

season. To increase the probability of removing the

problem bear, shooting should be done at the site where

damage has occurred. Bears are most easily attracted to

baits from dusk to dark. Place baits in the damaged area

where there are safe shooting conditions and clear

visibility. Use large, well-anchored carcass baits or

heavy containers filled with rancid meat scraps, fat

drippings, and rotten fruit or vegetables. Establish a

stand roughly 100 yards (100 m) downwind from the bait

and wait for the bear to appear. Strive for a quick

kill, using a rifle of .30 caliber or larger. The animal

must be turned over to wildlife authorities in most

states and provinces.

Calling bears with a

predator call has been reported to offer limited

success. If nothing else works, it can be tried. It is

best to use two people when calling since the bear may

come up in an ugly mood, out of sight of the caller. As

with any method of bear control, be cautious and use an

adequate-caliber rifle to kill the bear. Call in the

vicinity of the damage, taking proper precautions by

wearing camouflage clothing, orienting the wind to blow

the human scent away from the direction of the bear’s

approach, and selecting an area that provides clear

visibility for shooting. See Blair (1981) for

bear-calling methods. Some states allow the use of dogs

to hunt bears. Guides and professional hunters with bear

dogs can be called for help. Place the dogs on the track

of the problem bear. Often the dogs will be able to

track and tree the bear, allowing it to be killed, and

thus solving the bear problem quickly.

Avoiding Human-Bear Conflicts

Preventing Bear Attacks.

Black and grizzly bears must be respected. They have

great strength and agility, and will defend themselves,

their young, and their territories if they feel

threatened. Learn to recognize the differences between

black and brown bears. Knowledge and alertness can help

avoid encounters with bears that could be hazardous.

They are unpredictable and can inflict serious injury.

NEVER feed or approach a bear.

To avoid a bear encounter,

stay alert and think ahead. Always hike in a group.

Carry noisemakers, such as bells or cans containing

stones. Most bears will leave a vicinity if they are

aware of human presence. Remember that noisemakers may

not be effective in dense brush or near rushing water.

Be especially alert when traveling into the wind since

bears may not pick up your scent and may be unaware of

your approach. Stay in the open and avoid food sources

such as berry patches and carcass remains. Bears may

feel threatened if surprised. Watch for bear sign—fresh

tracks, digging, and scats (droppings). Detour around

the area if bears or their fresh sign are observed.

NEVER approach a bear cub.

Adult female black bears are very defensive and may be

aggressive, making threatening gestures (laying ears

back, huffing, chopping jaws, stomping feet) and

possibly making bluff charges. Black bears rarely attack

humans, but they have a tolerance range which, when

encroached upon, may trigger an attack. Keep a distance

of at least 100 yards (100 m) between you and bears.

Bears are omnivores,

eating both vegetable and animal matter, so don’t

encourage them by leaving food or garbage around camp.

When bears associate food with humans, they often lose

their fear of humans and are attracted to campsites.

Food-conditioned bears are very dangerous.

In established

campgrounds, keep your campsite clean, and lock food in

the trunk of your vehicle. Don’t leave dirty utensils

around the campsite, and don’t cook or eat in tents.

After eating, place garbage in containers provided by

the campground.

In the backcountry,

establish camp away from animal or walking trails and

near large, sparsely branched trees that can be climbed

should it become necessary. Choose another area if fresh

bear sign is present. Cache food away from your tent,

preferably suspended from a tree that is 100 yards (100

m) downwind of camp. Hang food from a strong branch at

least 15 feet (4.5 m) high and 8 feet (2.4 m) from the

trunk of the tree. Use bear-proof or airtight containers

for storing food and other attractants. Freeze-dried

foods are light-weight and relatively odor-free. Pack

out all noncombustible garbage. Burying it is useless

and dangerous. Bears can easily smell it and dig it up.

The attracted bear may then become a threat to the next

group of hikers. Always have radio communication and

emergency transportation available for remote base or

work camps, in case of accidents or medical emergencies.

Don’t take dogs into the

backcountry. The sight or smell of a dog may attract a

bear and provoke an attack. Most dogs are no match for a

bear. When in trouble, the dog may come running back to

the owner with the bear in pursuit. Trained guard dogs

are an exception and may be useful in detecting and

chasing away bears in the immediate area.

Bear Confrontations.

If a bear is seen at a distance, make a wide detour.

Keep upwind if possible so the bear can pick up human

scent and recognize human presence. If a detour or

retreat is not possible, wait until the bear moves away

from the path. Always leave an escape route and never

harass a bear.

If a bear is encountered

at close range, keep calm and assess the situation. A

bear rearing on its hind legs is not always aggressive.

If it moves its head from side to side it may only be

trying to pick up scent and focus its weak eyes. Remain

still and speak in low tones. This may indicate to the

animal that there is no threat. Assess the surroundings

before taking action. There is no guaranteed life-saving

method of handling an aggressive bear, but some behavior

patterns have proven more successful than others.

Do not run. Most bears can

run as fast as a racehorse, covering 30 to 40 feet (9 to

12 m) per second. Quick, jerky movements can trigger an

attack. If an aggressive bear is met in a wooded area,

speak softly and back slowly toward a tree. Climb a good

distance up the tree. Most black bears are agile

climbers, so a tree offers limited safety, but you can

defend yourself in a tree with branches or a boot heel.

Adult grizzlies don’t climb as a rule, but large ones

can reach up to 10 feet (3 m).

Occasionally, bears will

bluff by charging within a few yards (m) of an

unfortunate hiker. Sometimes they charge and veer away

at the last second. If you are charged, attempt to stand

your ground. The bear may perceive you as a greater

threat than it is willing to tackle and may leave the

area.

Black bears are less

formidable than grizzly bears, and may be frightened off

by acting aggressively toward the animal. Do not play

dead if a black bear is stalking you or appears to

consider you as prey. Use sticks, rocks, frying pans, or

whatever is available to frighten the animal away. As a

last resort, when attacked by a grizzly/brown bear,

passively resist by playing dead. Drop to the ground

face down, lift your legs up to your chest, and clasp

both hands over the back of your neck. Wearing a pack

will shield your body. Brown bears have been known to

inflict only minor injuries under these circumstances.

It takes courage to lie still and quiet, but resistance

is usually useless.

Many people who work in or

frequent bear habitat carry firearms for personal

protection. High-powered rifles (such as a .458 magnum

with a 510-grain soft-point bullet or a .375 magnum with

a 300-grain soft-point bullet) or shotguns (12-gauge

with rifled slugs) are the best choices, followed by

large handguns (.44 magnum or 10 mm). Although not a

popular solution, killing a bear that is attacking a

human is justifiable.

Economics of Damage and Control

Black bear damage to the

honey industry is a significant concern. Damage to

apiaries in the Peace River area of Alberta was

estimated at $200,000 in 1976. Damage incidents in

Yosemite National Park were estimated to be as high as

$113,197 in 1975, with $96,594 resulting from damage to

vehicles in which food was stored. Thirty percent of all

trees over 6 inches (15 cm) tall were reported to be

damaged by black bears on a 3,360 acre (1,630 ha) parcel

in Washington State. In Wisconsin, one female black bear

and her cubs caused an estimated $35,000 of damage to

apple trees during a two-day period in 1987. In general,

black bears can inflict significant economic damage in

localized areas. Some states pay for damage caused by

black bears. In western states, losses caused by black

bears are usually less than 10% of total predation

losses, although records are not complete. The extent of

claims paid are not high but usually are greater than

the license income that state wildlife agencies receive

from black bear hunters. Deems and Pursley (1983) listed

the states and provinces that pay for black bear

depredations.

Acknowledgments

Much of the text was

adapted from the chapter “Black Bears” by M. Boddicker

from the 1986 revision of Prevention and Control of

Wildlife Damage. Figure 1 from Schwartz and Schwartz

(1981).

Figure 2 from Graf et al.

(1992).

Figure 3 from Burt and

Grossenheider (1976), adapted by Dave Thornhill,

University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Figures 4 and 5 from

Hygnstrom and Craven (1986).

Figure 6 from Boddicker

(1986).

Figure 7 courtesy of

Gregerson Manufacturing Co., adapted by Jill Sack

Johnson.

Figure 8 from Manitoba

Fish and Wildlife agency publications, adapted by Jill

Sack Johnson.

Figure 9 by M. Boddicker.

For Additional Information

Blair, G. 1981. Predator

caller’s companion. Winchester Press, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

267 pp. Boddicker, M. L., ed. 1980. Managing Rocky

Mountain furbearers. Colorado Trapper’s Assoc., LaPorte,

Colorado. 176 pp.

Bromley, M., ed. 1989.

Bear-people conflicts: proceedings of a symposium on

management strategies. Northwest Terr. Dep. Renew.

Resour. Yellowknife. 246 pp.

Burt, W. H., and R. P.

Grossenheider. 1976. A field guide to the mammals, 3d

ed. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. 289 pp.

Davenport, L. B., Jr.

1953. Agriculture depredation by the black bear in

Virginia. J. Wildl. Manage. 17:331-340.

Deems, E. F., and D.

Pursley, eds. 1983. North American furbearers: a

contemporary reference. Int. Assoc. Fish Wildl. Agencies

and Maryland Dep. Nat. Resour. Annapolis, Maryland. 223

pp.

Erickson, A. W. 1957.

Techniques for livetrapping and handling black bears.

Trans. North Amer. Wildl. Conf. 22:520-543.

Graf, L. H., P. L.

Clarkson, and J. A. Nagy. 1992. Safety in bear country:

a reference manual, rev. ed. Northwest Terr. Dep. Renew.

Resour. Yellowknife. 135 pp.

Herrero, S. 1985. Bear

attacks: their causes and avoidance. New Century Publ.

Piscataway, New Jersey. 288 pp.

Hygnstrom, S. E., and S.

R. Craven. 1986. Bear damage and nuisance problems in

Wisconsin. Univ. Wisconsin Ext. Publ. G3000. Madison,

Wisconsin. 6 pp.

Hygnstrom, S. E., and T.

M. Hauge. 1989. A review of problem black bear

management in Wisconsin. Pages 163-168 in M. Bromley,

ed. Bear-people conflicts: proceedings of a symposium on

management strategies. Northwest Terr. Dep. Renew.

Resour. Yellowknife.

Jonkel, C. J., and I. McT.

Cowan. 1971. The black bear in the spruce-fir forest.

Wildl. Monogr. 27. 57 pp.

Jope, K. L. 1985.

Implications of grizzly bear habituation to hikers.

Wildl. Soc. Bull. 13:32-37.

Kolenosky, G. B., and S.

M. Strathearn. 1987. Black bear. Pages 442-454 in M.

Novak, J. A. Baker, M. E. Obbard, and B. Malloch, eds.

Wild furbearer management and conservation in North

America. Ontario Ministry of Nat. Resour. Toronto.

McArthur, K. L. 1981.

Factors contributing to effectiveness of black bear

transplants. J. Wildl. Manage. 45:102-110.

Meechan, W. R., and J. F.

Thilenius. 1983. Safety in bear country: protective

measures and bullet performance at short range. Gen.

Tech. Rep. PNW-152. US Dep. Agric., For. Serv. Portland,

Oregon. 16 pp.

Rogers, L. L. 1984.

Reactions of free-ranging black bears to capsaicin spray

repellent. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 12:58-61.

Rogers, L. L., D. W.

Kuehn, A. W. Erickson, E. M. Harger, L. J. Verme, and J.

J. Ozoga. 1976. Characteristics and management of black

bears that feed in garbage dumps, camp grounds or

residential areas. Int. Conf. Bear Res. Manage.

3:169-175.

Rutherglen, R. A. 1973.

The control of problem black bears. British Columbia

Fish Wildl. Branch, Wildl. Manage. Rep. 11. 78 pp.

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri, rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp. Singer, D. J.

1952. American black bear. Pages 97-102 in J. Walker

McSpadden, ed. Animals of the world. Garden City Books,

Garden City, New York.

Van Wormer, J. 1966. The

world of the black bear. J. B. Lippincott Co.,

Philadelphia. 168 pp.

Wynnyk, W. P., and J. R.

Gunson. 1977. Design and effectiveness of a portable

electric fence for apiaries. Alberta Rec., Parks, and

Wildl. Fish Wildl. Div. Alberta, Canada. 11 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994 Cooperative Extension Division

Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

James E. Miller

Program Leader, Fish and Wildlife

USDA — Extension Service Natural Resources and Rural

Development Unit

Washington, DC 20250

|