|

|

|

|

|

CARNIVORES: Badgers |

|

|

Identification

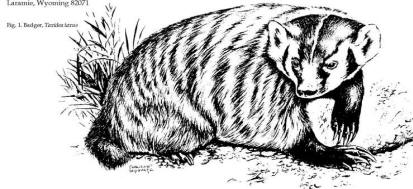

The badger (Taxidea

taxus) is a stocky, medium-sized mammal with a broad

head, a short, thick neck, short legs, and a short,

bushy tail. Its front legs are stout and muscular, and

its front claws are long. It is silver-gray, has long

guard hairs, a black patch on each cheek, black feet,

and a characteristic white stripe extending from its

nose over the top of its head. The length of this stripe

down the back varies. Badgers may weigh up to 30 pounds

(13.5 kg), but average about 19 pounds (8.6 kg) for

males and 14 pounds (6.3 kg) for females. Eyeshine at

night is green.

Fig.

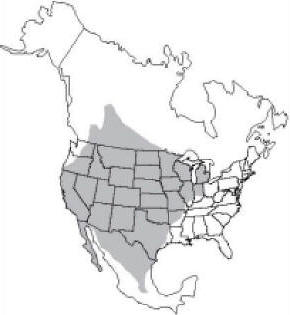

2. Range of the badger in North America. Fig.

2. Range of the badger in North America.

Range

The badger is widely

distributed in the contiguous United States. Its range

extends southward from the Great Lakes states to the

Ohio Valley and westward through the Great Plains to the

Pacific Coast, though not west of the Cascade mountain

range in the Northwest (Fig. 2). Badgers are found at

elevations of up to 12,000 feet (3,600 m).

Habitat

Badgers prefer open

country with light to moderate cover, such as pastures

and rangelands inhabited by burrowing rodents. They are

seldom found in areas that have many trees.

Food

Habits

Badgers are opportunists,

preying on ground-nesting birds and their eggs, mammals,

reptiles, amphibians, and insects. Common dietary items

are ground squirrels, pocket gophers, prairie dogs, and

other smaller rodents. Occasionally they eat vegetable

matter. Metabolism studies indicate that an average

badger must eat about two ground squirrels or pocket

gophers daily to maintain its weight. Badgers may

occasionally kill small lambs and young domestic

turkeys, parts of which they often will bury.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Badgers are members of the

weasel family and have the musky odor characteristic of

this family. They are especially adapted for burrowing,

with strong front legs equipped with long,

well-developed claws. Their digging capability is used

to pursue and capture ground-dwelling prey. Typical

burrows dug in pursuit of prey are shallow and about 1

foot (30 cm) in diameter. A female badger will dig a

deeper burrow (5 to 30 feet long [1.5 to 9 m]) with an

enlarged chamber 2 to 3 feet (0.6 to 0.9 m) below the

surface in which to give birth. Dens usually have a

single, often elliptical entrance, typically marked by a

mound of soil in the front.

Badgers have a rather

ferocious appearance when confronted, and often make

short charges at an intruder. They may hiss, growl, or

snarl when fighting or cornered. Their quick movements,

loose hide, muscular body, and tendency to retreat

quickly into a den provide protection from most

predators. Larger predators such as mountain lions,

bears, and wolves will kill adult badgers. Coyotes and

eagles will take young badgers.

Badgers are active at

night, remaining in dens during daylight hours, but are

often seen at dawn or dusk. During winter they may

remain inactive in their burrows for up to a month,

although they are not true hibernators. Male badgers are

solitary except during the mating season, and females

are solitary except when mating or rearing young.

Densities of badgers are reported to be about 1 per

square mile (0.4/km 2) although densities as high as 5

to 15 badgers per square mile (1.9 to 5.8/km2) have been

reported. An adult male’s home range may be as large as

2.5 square miles (6.5 km2); the home range of adult

females is typically about half that size. Badgers may

use as little as 10% of their range during the winter.

Badgers breed in summer

and early fall, but have delayed implantation, with

active gestation beginning around February. Some

yearling females may breed, but yearling males do not.

As many as 5 young, but usually 2 or 3, are born in

early spring. Young nurse for 5 to 6 weeks, and they may

remain with the female until midsummer. Most young

disperse from their mother’s range and may move up to 32

miles (52 km). Badgers may live up to 14 years in the

wild; a badger in a zoo lived to be 15 1/2 years of age.

Damage and Damage Identification

Most damage caused by

badgers results from their digging in pursuit of prey.

Open burrows create a hazard to livestock and horseback

riders. Badger diggings in crop fields may slow

harvesting or cause damage to machinery. Digging can

also damage earthen dams or dikes and irrigation canals,

resulting in flooding and the loss of irrigation water.

Diggings on the shoulders of roads can lead to erosion

and the collapse of road surfaces. In late summer and

fall, watch for signs of digging that indicate that

young badgers have moved into the area.

Badgers will occasionally

prey on livestock or poultry, gaining access to

protected animals by digging under fences or through the

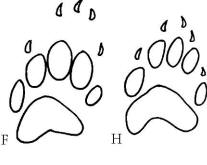

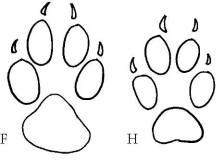

floor of a poultry house. Tracks can indicate the

presence of badgers, but to the novice, badger tracks

may appear similar to coyote tracks (see Coyotes ). Claw

marks are farther from the toe pad in badger tracks,

however, and the front tracks have a pigeon-toed

appearance (Fig. 3).

Badgers usually consume

all of a prairie dog except the head and the fur along

the back. This characteristic probably holds true for

much of their prey; however, signs of digging near the

remains of prey are the best evidence of predation by a

badger. Because badgers will kill black-footed ferrets,

their presence is of concern in reintroduction programs

for this endangered species.

BADGER

COYOTE TRACK

Fig. 3. Badger tracks

compared to coyote tracks.

Legal Status

In some states, badgers

are classified as furbearers and protected by regulated

trapping seasons, while in other states they receive no

legal protection. Contact your state wildlife agency

before conducting lethal control of badgers.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Mesh fencing buried to a depth of 12 to 18 inches

(30 to 46 cm) can exclude most badgers. The cost and

effort to construct such fences, however, preclude their

use for large areas.

Habitat Modification

Control of rodents, particularly burrowing rodents,

offers the greatest potential for alleviating problems

resulting from badger diggings. For example, controlling

ground squirrels or pocket gophers in alfalfa fields

will likely result in badgers hunting elsewhere.

Frightening

Badgers may be discouraged from a problem area by

the use of bright lights at night. High-intensity lamps

used to light up a farmyard may discourage badger

predation on poultry.

Trapping

Badgers can be removed by using live traps and/or

foothold traps set like those for coyotes (see Coyotes).

Snares have been used with mixed success. Badgers often

return to old diggings. A good bait for badgers is a

dead chicken placed within a recently dug burrow. Fur

trapping may reduce badger populations locally, but

badger pelts are generally of little value and most

badgers are caught incidentally.

Foothold traps (No. 3 or

4) are adequate to hold a badger. Rather than staking

the trap to the ground, it is better to attach it to a

drag such as a strong limb or similar object that the

badger cannot pull down into its burrow. Badgers will

often dig in a circle around a stake, sometimes enough

to loosen the stake and drag the trap away.

Shooting

Badgers can be controlled by shooting. Spotlighting,

if legal, can be effective. Incidental shooting has

contributed to reducing their numbers in some areas.

Acknowledgments

This chapter is a revision

of the chapter on badgers by Norman C. Johnson in the

1983 edition of Prevention and Control of Wildlife

Damage. F. Robert Henderson and Steve Minta provided

information included in this chapter.

Figures 1 and 2 from

Schwartz and Schwartz (1981).

Figure 3 from Wade (1973).

For Additional Information

Hawthorne, D. W. 1980.

Wildlife damage and control techniques. Pages 411-439 in

S. D. Schemnitz, ed. Wildlife management techniques

manual. The Wildl. Soc., Washington, DC.

Lindzey, F. C. 1982.

Badger. Pages 653-663 in J. A. Chapman and G. A.

Feldhamer, eds. Wild mammals of North America: biology,

management, and economics. The Johns Hopkins Univ.

Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Long, C. A. 1973. Taxidea

taxus . Mammal. Spec. 26:1-4.

Messick, J. P. 1987. North

American badger. Pages 584-597 in M. Novak, J. A. Baker,

M. E. Obbard, and B. Malloch, eds. Wild furbearer

management and conservation in North America. Ontario

Ministry of Nat. Resour.

Minta, S. C., and R. E.

Marsh. 1988. Badgers ( Taxidea taxus ) as occasional

pests in agriculture. Proc. Vertebr. Pest. Conf.

13:199-208.

Sargeant, A. B., and D. W.

Warner. 1972. Movements and denning habits of a badger,

J. Mammal. 53:207-210.

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri, rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp.

Wade, D. A. 1973. Control

of damage by coyotes and some other carnivores. Coop.

Ext. Serv. Pub. WR P-11, Colorado State Univ., Fort

Collins. 29 pp.

Wade, D. A., and J. E.

Bowns. 1982. Procedures for evaluating predation on

livestock and wildlife. Bull. B-1429, Texas A & M Univ.

System, College Sta., and the US Fish Wildl. Serv. 42

pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

03/28/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

James E. Miller

Program Leader, Fish and Wildlife

USDA — Extension Service Natural Resources and Rural

Development Unit

Washington, DC 20250

|