|

|

|

|

|

BIRDS: Woodpeckers |

|

|

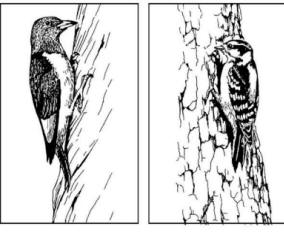

Fig. 1. Red-headed

woodpecker, Melanerpes erythrocephalus (left); downy

woodpecker, Picoides pubescens (right).

Identification

Woodpeckers belong to the

order Piciformes and the family Picidae, which also

includes flickers and sapsuckers. Twenty-one species

inhabit the United States. Woodpeckers have short legs

with two sharp-clawed, backward-pointed toes and stiff

tail feathers, which serve as a supportive prop. These

physical traits enable them to cling easily to the

trunks and branches of trees, wood siding, or utility

poles while pecking. They have stout, sharply pointed

beaks for pecking into wood and a specially developed

long tongue that can be extended a considerable

distance. The tongue is used to dislodge larvae or ants

from their burrows in wood or bark.

Woodpeckers are 7 to 15

inches (18 to 38 cm) in length, and usually have

brightly contrasting coloration. Most males have some

red on the head, and many species have black and white

marks. Identification of species by their markings is

quite easy. In most species, flight is usually

undulating, with wings folded against the body after

each burst of flaps.

Range

Woodpeckers are found

throughout the United States. The three most widely

distributed species are the hairy woodpecker (Picoides

villosus), the downy woodpecker (P. pubescens, Fig. 1),

and the yellow-bellied sapsucker (Sphyrapicus varius).

Different species are responsible for damage in

different regions.

Habitat

Because they are dependent

on trees for shelter and food, woodpeckers are found

mostly in or on the edge of wooded areas. They nest in

cavities chiseled into tree trunks, branches, or

structures, or use natural or preexisting cavities. Many

species nest in human-made structures, and have thus

extended their habitat to include wooden fence posts,

utility poles, and buildings. Because of this,

woodpeckers may be found in localities where trees are

scarce in the immediate vicinity.

Food

Habits

Most woodpeckers feed on

tree-living or wood-boring insects; however, some feed

on a variety of other insects. Some flickers obtain the

majority of their food by feeding on insects from the

ground, especially ants. Others feed primarily on

vegetable matter, such as native berries, fruit, nuts,

and certain seeds. In some areas, the diet includes

cultivated fruit and nuts. The sapsuckers, as the name

suggests, feed extensively on tree sap as well as

insects.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Woodpeckers are an

interesting and familiar group of birds. Their ability

to peck into trees in search of food or excavate nest

cavities is well known. They prefer snags or partially

dead trees for nesting sites, and readily peck holes in

trees and wood structures in search of insects beneath

the surface. One common misconception is that they peck

holes in buildings only in search of insects. While they

do obtain insects by this means, many species will drill

holes in sound dry wood of buildings, utility poles, and

fence posts where few or no insects exist. The acorn

woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus) drills holes in

wood simply to store acorns. When sapsuckers drill their

numerous rows of 1/4-inch (0.6-cm) holes in healthy

trees they are primarily after sap and the insects

entrapped by the sap.

Woodpeckers have

characteristic calls, but they also use a rhythmic

pecking sequence to make their presence known. Referred

to as “drumming,” it establishes their territories and

apparently attracts or signals mates. Drumming is

generally done on resonant dead tree trunks or limbs;

however, buildings and utility poles may also be used.

Woodpeckers breed in the

spring, commonly laying in the range of 3 to 5 or 4 to 6

eggs. The incubation period is generally short, lasting

from 11 to 14 days. It may be longer for larger species.

Most species are born naked; some are born downy. All

are tended by both parents. Having 2 broods per year is

fairly common and some species may have 3 broods.

Apparently, both sexes sleep in cavities throughout the

year.

Some species, such as the

northern flicker (Colaptes auratus) and the redheaded

woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus, Fig. 1), are

migratory, but most live year-round in the same area.

Most species live in small social groups; a few, such as

the Lewis’ woodpecker (Melanerpes lewis), may, in

certain seasons, occasionally be seen in flocks of

several hundred.

Damage and Damage Identification

Woodpecker damage to

buildings is a relatively infrequent problem nationwide,

but may be significant regionally and locally. Houses or

buildings with wood exteriors in suburbs near wooded

areas or in rural wooded settings are most apt to suffer

pecking and hole damage. Generally, damage to a building

involves only one or two birds, but it may involve up to

six or eight during a season. Most of the damage occurs

from February through June, which corresponds with the

breeding season and the period of territory

establishment.

The following species of

woodpeckers are most generally involved in damaging

homes or other wooden, human-made structures:

Woodpeckers

can be particularly destructive to summer or vacation

homes that are vacant during part of the year, since

their attacks often go undetected until serious damage

has occurred. For the same reason, barns and other

wooden outbuildings may also suffer severe damage. Woodpeckers

can be particularly destructive to summer or vacation

homes that are vacant during part of the year, since

their attacks often go undetected until serious damage

has occurred. For the same reason, barns and other

wooden outbuildings may also suffer severe damage.

Damage to wooden buildings

may take one of several forms. Holes may be drilled into

wood siding, eaves, window frames, and trim boards.

Woodpeckers prefer cedar and redwood siding, but will

damage pine, fir, cypress, and others when the choices

are limited. Natural or stained wood surfaces are

preferred over painted wood, and newer houses in an area

are often primary targets. Particularly vulnerable to

damage are rustic-appearing, channeled (grooved to

simulate reverse board and batten) plywoods with cedar

or redwood veneers. Imperfections (core gaps) in the

intercore plywood layers exposed by the vertical grooves

may harbor insects. The woodpeckers often break out

these core gaps, leaving characteristic narrow

horizontal damage patterns in their search for insects.

If a suitable cavity

results from woodpecker activities, it may also be used

for roosting or nesting.

The acorn woodpecker,

found in the West and Southwest, is responsible for

drilling closely spaced holes just large enough to

accommodate one acorn each. Wedging acorns between or

beneath roof shakes and filling unscreened rooftop

plumbing vents with acorns are also common activities.

Relatively new damage

problems are arising where damage-susceptible materials

such as plastic are used for rooftop water-heating solar

panels or where electrical solar panels are used.

Woodpeckers have also reportedly damaged elevated

plastic irrigation lines in several vineyards in

California.

Widespread damage from

nest cavities and acorn holes in utility poles in some

regions has necessitated frequent and costly replacement

of weakened poles. Similar damage to wooden fence posts

can also be a serious problem for some farmers and

ranchers. Occasionally, woodpeckers learn that beehives

offer an extraordinary food resource and drill into

them.

Drumming, the term given

to the sound of pecking in rapid rhythmic succession on

metal or wood, causes little damage other than possible

paint removal on metal surfaces; however, the noise can

often be heard throughout the house and becomes quite

annoying, especially in the early morning hours when

occupants are still asleep. Drumming is predominantly a

springtime activity. Drumming substrates are apparently

selected on the basis of the resonant qualities. They

often include metal surfaces such as metal gutters,

downspouts, chimney caps, TV antennas, rooftop plumbing

vents, and metal roof valleys. Drumming may occur a

number of times during a single day, and the activity

may go on for some days or months. Wood surfaces may be

disfigured from drumming but the damage may not be

severe.

Sapsuckers bore a series

of parallel rows of 1/4- to 3/8-inch (0.6- to 1.0-cm)

closely spaced holes in the bark of limbs or trunks of

healthy trees and use their tongues to remove the sap

(Fig. 2). The birds usually feed on a few favorite

ornamental or fruit trees. Nearby trees of the same

species may be untouched. Holes may be enlarged through

continued pecking or limb growth, and large patches of

bark may be removed or sloughed off. At times, limb and

trunk girdling may kill the tree.

On forest trees, the

wounds of attacked trees may attract insects as well as

porcupines or tree squirrels. Feeding wounds also serve

as entrances for diseases and wood-decaying organisms.

Wood-staining fungi and bacteria may also enter the

wounds, reducing the quality of the wood when cut.

Woodpecker damage to hardwood trees can be costly.

Wounds cause a grade defect called “bird peck” that

lowers the value of hardwoods. Damage occurs to both

commercial hardwoods and softwoods. Certain tree species

are preferred over others, but the list of susceptible

trees is extensive.

As mentioned previously,

vegetable matter makes up a good portion of the food of

some woodpeckers, and native fruits and nuts play an

important role in their diet. Cultivated fruits and nuts

may also be consumed. Birds involved in orchard

depredation are often so few in number that damage is

limited to only a small percentage of the crop. The crop

of a couple of isolated backyard fruit or nut trees may,

however, be severely reduced prior to harvest.

In recent times, controls

against woodpeckers to protect commercial crops have

only rarely been necessary. Published accounts suggest

that these isolated instances occurred mostly in the

fruit-growing states of the far West where the Lewis’

woodpecker (Melanerpes lewis), whose flocks may number

several hundred, is most often implicated.

Fig.

2. Yellow-bellied sapsucker, Sphyrapicus varius Fig.

2. Yellow-bellied sapsucker, Sphyrapicus varius

Legal Status

Woodpeckers are classified

as migratory, nongame birds and are protected by the

Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act. The red-cockaded

woodpecker (Picoides borealis) and the ivory-billed

woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) are on the

Endangered Species list and are thus offered full

protection. When warranted, woodpeckers other than the

endangered species can be killed but only under a permit

issued by the Law Enforcement Division of the US Fish

and Wildlife Service upon recommendation of

USDA-APHIS-Animal Damage Control personnel. Generally,

there must be a good case to justify issuance of a

permit.

Woodpeckers are commonly

protected under state laws, and in those instances a

state permit may be required for measures that involve

lethal control or nest destruction. Other methods of

reducing woodpecker damage do not infringe upon their

legal protection status. Threatened or endangered

species, however, cannot be harassed.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

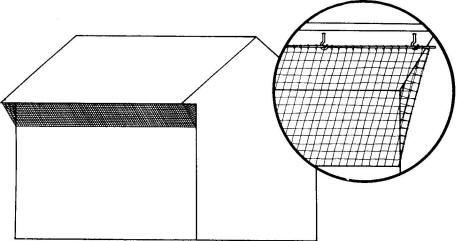

Fig.

3. Plastic netting attached to a building from the

outside edge of the eave and angled back to the wood

siding. Insert shows one method of attachment using

hooks and wooden dowels. Fig.

3. Plastic netting attached to a building from the

outside edge of the eave and angled back to the wood

siding. Insert shows one method of attachment using

hooks and wooden dowels.

Exclusion

Netting. One of the most

effective methods of excluding woodpeckers from damaging

wood siding beneath the eaves is to place lightweight

plastic bird-type netting over the area. A mesh of 3/4

inch (1.9 cm) is generally recommended. At least 3

inches (7.6 cm) of space should be left between the

netting and the damaged building so that birds cannot

cause damage through the mesh. The netting can also be

attached to the overhanging eaves and angled back to the

siding below the damaged area and secured taut but not

overly tight (Fig. 3). Be sure to secure the netting so

that the birds have no way to get behind it. If

installed properly, the netting is barely visible from a

distance and will offer a long-term solution to the

damage problem. If the birds move to another area of the

dwelling, that too will need to be netted.

Netting is becoming

increasingly popular as a solution to woodpecker

problems because it consistently gives desired results.

Metal barriers. Place

metal sheathing or plastic sheeting over the pecked

areas on building siding to offer permanent protection

from continued damage. Like all repelling methods, metal

barriers work best if installed as soon as damage

begins. Occasionally the birds will move over to an

unprotected spot and the protected area must be

expanded. Aluminum flashing is easy to work with to

cover damaged sites. Woodpeckers will sometimes peck

through aluminum if they can secure a foothold from

which to work. Metal sheathing can be disguised with

paint or simulated wood grain to match the siding.

Quarter-inch (0.6-cm)

hardware cloth has also been used to cover pecked areas

and prevent further damage. It can be spray painted to

match the color of the building. The wire can either be

attached directly to the wood surface being damaged, or

raised outward from the wood siding with 1-inch (2.5-cm)

wood spacers.

Once the woodpeckers have

been discouraged, frightened away, or killed, the

damaged spots on houses should be repaired by filling in

the holes with wood patch or covering them to prevent

woodpeckers from being attracted to the damaged site at

some future time.

Some of the harder

compressed wood or wood-fiber siding materials cannot be

damaged by woodpeckers. Presumably, their hardness

and/or smooth surface serve as deterrents. Aluminum

siding can also be used as an alternative to wood

siding.

To protect trees from

sapsuckers, wrap barriers of 1/4-inch (0.6-cm) hardware

cloth, plastic mesh, or burlap around injured areas to

discourage further damage. This method may be practical

for protecting high-value ornamental or shade trees. In

orchards and forested areas it may be best to let the

sapsuckers work on one or more of their favorite trees.

Discouraging them from select trees may encourage the

birds to disperse to others, causing damage to a greater

number of trees.

Frightening Devices

Visual. Stationary model

hawks or owls, fake and simulated snakes, and owl and

cat silhouettes are generally considered ineffective as

repellents. Toy plastic twirlers or windmills fastened

to the eaves, and aluminum foil or brightly colored

plastic strips, bright tin lids, and pie pans hung from

above, all of which repel by movement and/or reflection,

have been used with some success, as have suspended

falcon silhouettes, especially if put in place soon

after the damage starts. The twirlers and plastic strips

rely on a breeze for motion. Stretching reflective mylar

tape strips across a damaged area, or attaching them to

the eaves and letting them hang down (weighted or

unweighted) is a recent alternative to aluminum strips.

Large rubber balloons with owl-like eyes painted on them

are included in the recent array of frightening devices

used to scare woodpeckers.

A good deal of attention

has recently been given to round magnifying-type shaving

mirrors installed over or adjacent to damaged areas to

frighten woodpeckers with their larger-than-life

reflections. Success is sometimes reported by those

using the method and this encourages further testing.

Contrarily, woodpeckers are not discouraged from

damaging wooden window frames or casings very near to

window panes where their own reflection would frequently

be seen. In fact, some believe that seeing their own

reflection intensifies the damage as a result of

defensive territorial behavior.

Sound. Loud noises such as

hand-clapping, a toy cap pistol, and banging on a

garbage can lid have been used to frighten woodpeckers

away from houses. Such harassment, if repeated when the

bird returns, may cause it to leave for good.

Propane exploders (gas

cannons) or other commercial noise-producing,

frightening devices may have some merit for scaring

woodpeckers from commercial orchards, at least for short

periods. Because of the noise they produce, they are

rarely acceptable near inhabited dwellings or

residential areas. Around homes, portable radios have

been played with little success in discouraging

woodpeckers. Expensive high-frequency sound-producing

devices are marketed for controlling various pest birds

but rarely provide advertised results. High-frequency

sound is above the normal audible hearing range of

humans but, unfortunately, above the range of most birds

too.

Woodpeckers can be very

persistent and are not easily driven from their

territories or selected pecking sites. For this reason,

visual or sound types of frightening devices for

protecting buildings — if they are to be effective at

all — should be employed as soon as the problem is

identified and before territories are well established.

Visual and sound devices often fail to give desired

results and netting may have to be installed.

Repellents

Taste. Many chemicals that

have objectionable tastes as well as odors have been

tested for treating utility poles and fence posts to

discourage woodpeckers. Most have proven ineffective or

at least not cost-effective.

Odor. Naphthalene

(mothballs) is a volatile chemical that has been

suggested for woodpecker control. In out-of-door

unconfined areas, however, it is of doubtful merit. It

is unlikely that high enough odor-repelling

concentrations of napthalene could be achieved to

effectively repel woodpeckers.

Odorous and somewhat toxic

wood treatments, such as creosote and pentachlorophenol,

which are frequently used to treat utility poles and

fence posts, do not resolve the woodpecker problem.

Tactile. Sticky or tacky

bird repellents such as Tanglefoot®, 4-The-Birds®, and

Roost-No-More®, smeared or placed in wavy bands with a

caulking gun on limbs or trunks where sapsuckers are

working, will often discourage the birds from orchard,

ornamental, and shade trees. These same repellents can

be effective in discouraging birds if applied to wood

siding and other areas of structural damage. The birds

are not entrapped by the sticky substances but rather

dislike the tacky footing. A word of caution: some of

the sticky bird repellents will discolor painted,

stained, or natural wood siding. Others may run in warm

weather, leaving unsightly streaks. It is best to try

out the material on a small out-of-sight area first

before applying it extensively. The tacky repellents can

be applied to a thin piece of pressed board, ridged

clear plastic sheets, or other suitable material, which

is then fastened to the area where damage is occurring.

For sources of sticky or tacky bird repellents, refer to

Supplies and Materials.

Toxicants

Toxicants have only rarely

been used to protect fruit crops. Woodpecker problems

can be resolved without toxicants and none are

registered for such use.

Trapping

Wooden-base rat snap traps

can be effective in killing the offending birds. Federal

and, most likely, state permits are required. The trap

is nailed to the building with the trigger downward

alongside the spot sustaining the damage. The trap is

baited with nut meats (walnuts, almonds, or pecans) or

suet. If multiple areas are being damaged, several traps

can be used.

Live traps have been tried

in attempts to capture woodpeckers for possible

relocation rather than killing the birds. None of those

explored were very successful, and more research is

needed to develop an effective woodpecker live trap.

Shooting

Where it is necessary to

remove the offending birds and the proper permits have

been obtained, shooting may be one of the quickest

methods of dispatching one or a few birds. The

discharging of firearms is often subject to local

regulations in residential areas.

At close range, air rifles

or .22-caliber rifles with dust shot or BB caps can be

effective. Shotguns or .22-caliber rifles may be needed

for birds that must be taken from greater distances.

Considerable discretion must be used around dwellings.

Bullets and shot can travel long distances if they miss

their targets.

With appropriate permits,

shooting has been occasionally used to reduce woodpecker

damage in commercial fruit and nut orchards.

Other Methods

Suet. Placing suet

stations near damaged buildings, especially in colder

parts of the country, has been recommended to entice

woodpeckers away from buildings or damaged areas. Suet

offered in the warmer seasons of the year, however, may

be potentially harmful to woodpeckers. The suet gets

onto the feathers of the head, which may lead to matting

and eventual loss of feathers. Some damage control

experts believe that any feeding of birds contributes to

the problem and recommend against it.

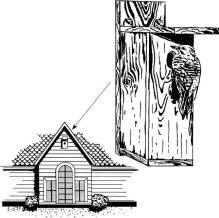

Nest boxes. All North

American woodpeckers are primarily cavity nesters that

excavate their own cavities, but some of these species,

such as golden-fronted, hairy, red-bellied, and

red-headed woodpeckers, do occasionally use existing

cavities or nest boxes (Fig. 4).

Northern flickers

apparently use artificial boxes more often than any

other woodpecker species. Some success has been achieved

with the placement of cavity-type nest boxes on the

building in the vicinity of damage by northern flickers.

A thick layer of sawdust should be placed in the bottom

of the box; better yet, some have found that filling the

box completely full of sawdust entices the bird to

remove the sawdust to the desired level. Possibly, the

bird is fooled into thinking it is constructing its own

nest. Working against the nest box is the fact that with

primary cavity nesters, the preparation of the new

cavity often seems a part of the breeding ritual. New

cavities are often constructed even where preexisting

empty cavities are available. The use of nest boxes is

definitely worth trying in an area where visual or sound

methods have failed and where woodpecker populations are

desired. Nesting woodpeckers defend their territories

and keep other woodpeckers away. What effect such boxes

will have on increasing local woodpecker populations is

unknown. Nest boxes are constructed of wood with an

entrance hole 16 to 20 inches (40 to 50 cm) above the

floor and about 2 1/2 inches (6 cm) in diameter. Inside

floor dimensions should be about 6 x 6 inches (15 x 15

cm) and the total height of the box is 22 to 26 inches

(56 to 66 cm). A front-sloping hinged roof will shed

rain and provide easy access. Place the boxes at about

the same height as the height of the structural damage.

Insecticides for indirect

control are based on the premise that woodpeckers are

after insects, some control bulletins suggest treating

insect-infested siding with an appropriate insecticide

as a remedy for damage. While this may have some merit

with insect-infested wood, woodpeckers often attack

siding, poles, and posts that are sound and without

insects. The use of insecticides for indirect control in

these instances would be unfounded. Depending on their

chemical nature, insecticides may have an adverse effect

on the birds. Where the situation warrants the

application of an insecticide, it should be selected on

the basis of its safety for birds.

Fig.

4. Artificial nest boxes are used by some species,

especially the northern flicker. Fig.

4. Artificial nest boxes are used by some species,

especially the northern flicker.

Economics of Damage and Control

Little has been published

on the economics of damage to buildings and other

human-made structures. Most of what does exist relates

to damage to utility poles because companies keep good

records of these losses and the cost of replacements.

For example, from 1981 to 1982 the Central Missouri

Electric Cooperative replaced 2,114 woodpecker-damaged

poles in their system at an estimated cost of $560,000.

Economic losses to the timber industry in terms of

damaged trees and reduction in wood quality have also

been documented in several regions. Such published

information is of a localized nature; the extent of

damage on a nationwide basis is unknown. Little is

published on the economic damage to buildings, although

it is known to be substantial in some instances. In a

survey of woodpecker damage to homes, Craven (1984)

reported an average loss of $300 per bird incident.

Damage to homes was estimated at $50,000 to $500,000

annually in Michigan, a conservative $50,000 in

Louisiana, and over $100,000 in Wisconsin. The economics

of control are relatively unknown because in most

situations it is difficult to predict what the damage

might have been if no control was undertaken.

Some success has been

achieved with the placement of cavity-type nest boxes on

the building in the vicinity of damage by northern

flickers. A thick layer of sawdust should be placed in

the bottom of the box; better yet, some have found that

filling the box completely full of sawdust entices the

bird to remove the sawdust to the desired level.

Possibly, the bird is fooled into thinking it is

constructing its own nest. Working against the nest box

is the fact that with primary cavity nesters, the

preparation of the new cavity often seems a part of the

breeding ritual. New cavities are often constructed even

where preexisting empty cavities are available.

The use of nest boxes is

definitely worth trying in an area where visual or sound

methods have failed and where woodpecker populations are

desired. Nesting woodpeckers defend their territories

and keep other woodpeckers away. What effect such boxes

will have on increasing local woodpecker populations is

unknown.

Nest boxes are constructed

of wood with an entrance hole 16 to 20 inches (40 to 50

cm) above the floor and about 2 1/2 inches (6 cm) in

diameter. Inside floor dimensions should be about 6 x 6

inches (15 x 15 cm) and the total height of the box is

22 to 26 inches (56 to 66 cm). A front-sloping hinged

roof will shed rain and provide easy access. Place the

boxes at about the same height as the height of the

structural damage.

Acknowledgments

Information used in this

section draws upon the author’s personal experience and

a variety of scientific and applied references and

extension leaflets.

Figures 1 and 2 by Emily

Oseas Routman.

Figure 3 from W. P.

Gorenzel and T. P. Salmon (1982).

Figure 4 by Renee Lanik,

University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

For Additional Information

Carlton, R. L. 1976. Woodpeckers and houses. Coop. Ext.

Serv., Univ. Georgia, College of Agric. Leaflet 239. 6

pp.

Craven, S. R. 1984.

Woodpeckers: A serious suburban problem? Proc. Vertebr.

Pest Conf. 11:204-210.

Dennis, J. V. 1967. Damage

by golden-fronted and ladder-backed woodpeckers to fence

and utility poles in South Texas. Wilson Bull. 79:75-88.

Evans, D., J. L. Byford,

and R. H. Wainberg. 1984. A characterization of

woodpecker damage to houses in East Tennessee. Proc.

Eastern Wildl. Damage Control Conf. 1:325-330.

Gorenzel, W. P., and T. P.

Salmon. 1982. The cliff swallow — biology and control.

Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 10:179-185.

Henderson, F. R., and C.

Lee. 1992. Woodpeckers. Coop. Ext. Serv. Kansas State

Univ., Manhattan. Leaflet L-866. 5 pp.

Jackson, J. A., and E. E.

Hoover. 1975. A potentially harmful effect of suet on

woodpeckers. Bird-Banding 46:131-134.

Linn, J. W. 1982.

Woodpeckers. Pest Control 50(6):28, 30.

Marsh, R. E., and W. E.

Howard. 1990. Vertebrate Pests. Pages 771-831 in A.

Mallis, ed. Handbook of pest control 7th ed. Franzak and

Foster Co., Cleveland, Ohio.

Stemmerman, L. A. 1988.

Observation of woodpecker damage to electrical

distribution line poles in Missouri. Proc. Vertebr. Pest

Conf. 13:260-265.

US Fish and Wildlife

Service. 1978. Controlling woodpeckers. US Dep. Inter.,

Fish Wildl. Serv. ADC 101. 4 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control E-139

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

01/09/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|