|

|

|

|

|

BIRDS: Waterfowl |

|

|

Fig. 1. Geese, ducks, and

other waterfowl may damage crops by feeding in fields.

Identification

The term waterfowl is

properly applied only to ducks, geese, and swans (Fig.

1). Space does not permit full species descriptions

here. A bird identification guide should be consulted

for exact species descriptions.

Many of the control

techniques are equally applicable to damage situations

involving coots, rails, and cranes, which are not

discussed in this publication.

Range

In North America, most

waterfowl are migratory, flying long distances in the

spring and fall between the summer breeding grounds and

wintering areas. Some species or geographic populations

of some species, however, never leave the breeding

areas. The Florida and mottled ducks, southern

populations of wood ducks and hooded mergansers, and

some populations of Canada geese are nonmigratory.

Ducks and geese breed

throughout North America. The primary goose production

areas for Central, Mississippi, and Atlantic Flyway

geese are Banks Island, Baffin Island, and the greater

Hudson Bay area. Most of these birds winter in the

southern Great Plains, Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi

coastal marshes, or the Chesapeake Bay and mid-Atlantic

states’ coastal marshes and barrier islands.

The primary breeding

grounds for geese using the Pacific Flyway are the

Yukon, Kuskokwin, and Copper River deltas and the north

and west coasts of Alaska. These birds typically winter

in Washington, Oregon, and California (especially Baja

California, the Baja California Sur coastal marshes, and

the central valley of California).

The primary North American

breeding grounds for ducks are the prairie pothole

region of Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Montana,

North and South Dakota, and Minnesota. Historically,

this area probably produced more ducks than the rest of

the continent combined. Other important breeding areas

include coastal and interior Alaska, and the Mackenzie

River Delta. Primary duck wintering grounds include the

central valley of California, the southern Great Plains,

Gulf Coast marshes, Caribbean Islands, and Central and

South America.

Many of the historical

North American waterfowl breeding, migrating, and

wintering areas are changing because of agricultural and

land-clearing practices, northern prairie pothole

drainage, and development of the US Fish and Wildlife

Service’s National Wildlife Refuge system. Worldwide,

waterfowl occur on every major land mass except

Antarctica.

Habitat

Waterfowl, as their name

implies, are most often found near water. They can,

however, fly long distances to and from favorite feeding

grounds, which may include agricultural or upland sites.

Some species, such as the mallard and certain subspecies

of Canada geese, are extremely adaptable. They are

equally at home in rural and urban environments, on a

pond in a city park, or on a marsh in Alaska.

Food Habits

The food of individual

waterfowl species ranges from fish to insects to plants

in various combinations, depending on availability.

Waterfowl bills have evolved to allow the exploitation

of a wide variety of food sources and associated

habitats. Even though many species are adapted to

feeding in the water, most will readily come on land to

take advantage of available food. Since space does not

permit a species-by-species description of food habits,

a few general comments will suffice.

During the prefledging

period, young waterfowl feed primarily on aquatic

insects and other invertebrates. As adults, waterfowl

have an omnivorous diet. Dabbling ducks, whistling

ducks, and shovelers are primarily filter feeders and

will consume almost anything edible. Torrent ducks, blue

ducks, and scaups feed heavily on aquatic insect larvae,

snails, and other invertebrates found on and under rocks

in streams and ponds. Large eiders, scoters, and steamer

ducks feed heavily on mollusks and shellfish. Steller’s

eider feeds more on soft-shelled invertebrates. Fish are

the main food of mergansers. Swans are aquatic grazers

and geese are terrestrial grazers.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Waterfowl are normally

monogamous and solitary nesters. The size of the nesting

territory is determined by the aggressiveness of the

particular pair of birds. Pair formation in geese and

swans tends to be permanent until one of the pair dies;

the remaining bird will often remate. Ducks seek a new

mate each year.

Ducks and the Ross’s goose

generally lay one egg each day until the clutch is

complete. Most other geese and probably all swans lay an

egg every other day until the clutch is complete.

Incubation is not started until the last or

next-to-the-last egg is laid, thus all the eggs hatch at

about the same time. There is a slight correlation

between the length of incubation and the size of the

adult bird. Incubation periods range from about 23 days

for cackling Canada geese, 28 days for giant Canada

geese and mallards, to 38 days for trumpeter swans.

Young waterfowl are precocial and begin foraging shortly

after hatching. The nest site is abandoned 1 to 2 days

after hatching.

Studies indicate many

species have a first-year mortality rate of 60% to 70%

and a 35% to 40% mortality rate in subsequent years.

Life spans of 10 to 20 years for captive ducks and 20 to

30 for captive geese and swans are not uncommon.

Damage and Damage Identification

Goose problems in urban

and suburban areas are primarily caused by giant Canada

geese, which are probably the most adaptable of all

waterfowl. If left undisturbed, these geese will readily

establish nesting territories on ponds in residential

yards, golf courses, condominium complexes, city parks,

or on farms. Most people will readily welcome a pair of

geese on a pond. They can soon turn from pet to pest,

however. A pair of geese can, in 5 to 7 years, easily

become 50 to 100 birds that are fouling ponds and

surrounding yards and damaging landscaping, gardens, and

golf courses. Defense of nests or young by geese and

swans can result in injuries to people who come too

close.

Migrant waterfowl damage

agricultural crops in northern and central North

American. In the spring, waterfowl graze and trample

crops such as soybeans, sunflowers, and cereal grains.

In autumn, swathed grains are vulnerable to damage by

ducks, coots, geese, and cranes through feeding,

trampling, and fouling. Young alfalfa is susceptible to

damage by grazing waterfowl. Geese sometimes damage

standing crops such as corn, soybeans, and wheat. In

southern agricultural areas, overwintering waterfowl can

cause problems in rice, lettuce, and winter wheat.

Mergansers, mallards, and

black ducks cause problems at some aquaculture

facilities by feeding on fish fry and fingerlings.

Common eiders and black and surf scoters cause problems

when they feed in commercial blue mussel and razor clam

beds. For more information, see Bird Damage at

Aquaculture Facilities.

Legal Status

In the United States,

migratory birds, including most waterfowl, as well as

their nests and eggs, are federally protected (50 CFR

10.12) by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) (16 USC.

703711). A complete list of all migratory birds

protected by the MBTA can be found in 50 CFR 10.13.

Also, all states protect most waterfowl. Exotic and

feral waterfowl species including mute swans, greylag

geese, muscovy ducks, and Pekin ducks are not protected

by the MBTA, but may be protected by state law or local

ordinance. Persons wishing to take any migratory bird

outside of the legal hunting season must first secure a

federal permit from the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS),

and in some cases a state permit. “Take” means to

pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or

collect, or attempt to pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill,

trap, capture, or collect (50 CFR 10.12). “A federal

permit is not required to merely scare or herd

depredating migratory birds other than endangered or

threatened species or bald or golden eagles” (50 CFR

21.43a). Three species and one subspecies of waterfowl

that occur in the United States are listed as endangered

in 50 CFR 17.11, October 1, 1992 edition (Table 1). In

addition, five subspecies of rails, and one species and

one subspecies of crane are listed.

Contact personnel from

your local USDA-APHIS-ADC office for information on

obtaining a federal permit to take migratory birds.

“Landowners, sharecroppers, tenants, or their employees

or agents actually engaged in the production of rice in

Louisiana may, without a permit, shoot purple gallinules

(Ionornis martinica) when found committing or about to

commit serious depredations to growing rice crops on the

premises owned or occupied by such persons . . . between

May 1 and August 15 in any year.” (50 CFR 21.45).

Table 1. Members of the

families Anatidae (ducks, geese, and swans), Rallidae

(coots and rails), and Gruidae (cranes) occurring in the

United States listed as endangered in the Code of

Federal Regulations, Title 50, Sec. 17.11, 10-1-92

edition.

ANATIDAE:

Laysan duck (Anas laysanensis)

Hawaiian duck (Anas wyvilliana)

Aleutian Canada goose (Branta canadensis leucopareia)

Hawaiian goose (Nesochen sandvicensis)

RALLIDAE:

Hawaiian coot (Fulica Americana alai)

California clapper rail (Rallus longirostris obsoletus)

Light-footed clapper rail (Rallus longirostris levipes)

Yuma clapper rail (Rallus longirostris yumanensis)

Hawaiian moorhen (Galinula chloropus sanduicensisie)

GRUIDAE:

Mississippi sandhill crane (Grus canadensis pulla)

Whooping crane (Grus americana)

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Waterfowl can be difficult

to disperse once they become established on a pond or

feeding site. Promptness and persistence are the keys to

success when attempting to repel nuisance or depredating

waterfowl. Frightening devices and repellents should be

in place before the damage starts to prevent the birds

from becoming acclimated to the site.

Habitat Modification

Discourage geese and other waterfowl from using a

pond by making it and the surrounding area unattractive

to them. Reduce nesting, loafing, and escape cover by

mowing to the edge of the pond, and by using herbicides

to eliminate emergent aquatic vegetation. Contact your

local Cooperative Extension office for specific

recommendations for vegetation management in ponds.

Reduce or eliminate fertilizer applications to the

surrounding grass area to make the grass less

nutritionally attractive to grazing waterfowl. Feeding

of waterfowl around the pond site should be prohibited.

In cold climates, shut off pond aerators in the winter

and allow the pond to freeze.

Giant Canada geese

generally will not establish nesting territories in

areas where they cannot easily walk in and out of the

local pond. Construct new ponds so there is an 18-to

24-inch (45to 60-cm) vertical bank at the water’s edge.

Discourage Canada geese from using existing ponds by

vertically straightening the banks or by erecting a 30-

to 36-inch (75-to 90-cm) high poultry-wire fence around

the pond at the water’s edge. Use large boulder rip-rap,

which geese cannot easily climb over, in locations such

as levees or banks around airport runways. Caution:

Large boulder rip-rap may provide nesting or loafing

habitat for some species of gulls.

Exclusion

Construct overhead grids of 0.015-to 0.030-inch

(0.4-to 0.8-mm) stainless steel spring wire, or

0.071-inch (1.8-mm) and heavier ultraviolet-protected

monofilament line to stop waterfowl from using

reservoirs, lakes, ponds, and fish-rearing facilities.

Several hundred feet (m) of monofilament line or

stainless steel wire can be supported between two

standard, 5-foot (1.5-m), steel fence posts, because

these materials are extremely light. The 0.072-inch

(0.18-cm) polyester line weighs about 12.1 pounds per

mile (3.4 kg/km); 0.016-inch (0.041-cm) stainless steel

wire weighs about 4 pounds per mile (1.14 kg/km).

Construct grids on 20-foot

(6-m) centers to stop geese; grids with 10-foot (3-m)

centers will stop most ducks. Grid wire spacing may need

to be reduced to 5 feet (1.5 m) or less to stop all

waterfowl. In most instances, grid lines should be

installed high enough to allow people and equipment to

move beneath them. Tie the grid wires together wherever

two lines cross to prevent rubbing. Excessive rubbing

will result in line breakage. Independently attach lines

to each post and not in a constant run. This will

prevent having to rebuild the entire grid when one line

breaks.

Where aesthetics or other

factors preclude overhead grids, grids can be installed

at the water surface, or no more than 1 inch (2.5 cm)

below. In these installations, grid wire spacing should

be no more than 5 feet (1.5 m).

Use 1- to 1.5-inch (2.5-

to 3.75-cm) mesh polypropylene UV-protected netting when

total exclusion is needed, as in contaminated oil

containment basins. Support the netting with at least

0.19-inch (0.46-cm), 7 x 19-strand galvanized coated

cable on 20-foot centers. The support cables must be

well-anchored to carry the weight of the netting and to

allow the cable to be stretched tight to reduce sag as

much as possible. High winds are the greatest hazard to

this type of netting installation. Attach the netting to

the support cables to prevent wind-caused abrasion.

Abrasion can be more damaging than UV radiation.

Three-foot (1-m)

poultry-wire fences around gardens or yards will help

keep geese out of such places, as adult geese with young

will not cross a fence and leave their young behind.

Good results have also been reported using 20-pound test

(9-kg), or heavier, monofilament line to make a 2-to

3-strand fence in situations where aesthetics preclude

the use of woven-wire fencing. String the first line 6

inches (15 cm) off the ground, with each additional line

spaced 6 inches (15 cm) above the preceding line.

Suspend thin strips of aluminum foil at 3-to 6-foot

(1-to 2-m) intervals along the lines to increase

visibility of the barrier. Best results are obtained

when the monofilament line fence is in place before

geese start grazing.

Half-inch (11-mm) mylar

tape can also be used to construct 2- to 3-strand

vertical goose-resistant fencing around lawns, gardens,

and crop areas. Place the first strand 1 foot (0.3 m)

above the ground, with each succeeding strand 1.5 feet

(0.5 m) above the previous strand.

Commercial clam growers

have been able to protect their clam beds from common

eiders by covering them with heavy 0.5-inch (1.27-cm)

mesh nylon netting. Mussel ropes can be protected from

scoters and eiders by suspending them in cages made of

0.25-inch (0.64-cm) mesh plastic coated wire fencing.

Caution: Birds may become entangled in the netting or

wire and drown. This could expose the owner to

prosecution under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Cultural Methods

Agricultural Crops. Agricultural damage caused by

waterfowl can be reduced by timing crop planting or

harvest periods so they do not coincide with periods of

migration. For example, teal may damage early-planted

rice in some southern states. Rice that is planted in

April, however, after the birds have migrated north, is

relatively safe from damage by waterfowl.

Spring grains are

vulnerable to waterfowl damage in some northern regions

because of the agricultural practices required for their

production. Many spring grains are swathed at harvest

time, allowed to dry in the field, and then combined.

The short growing season, possible early frost, uneven

soil types, and topography sometimes prevent the even

ripening needed for straight combining. In areas of

severe waterfowl damage, farmers should consider the use

of on-farm or commercial grain dryers so that high-mois-ture

grain can be combined early. Early harvest and forced

drying of high-moisture grain, however, is expensive,

and can result in shrinkage and reduction of grain

quality.

Where conditions permit,

the production of winter grains instead of spring grains

may help eliminate waterfowl damage. Winter grains can

normally be straight combined in July and August, long

before migrating waterfowl arrive in the area.

Admittedly, a winter grain’s rosette of leaves is

vulnerable to grazing and puddling damage by waterfowl

in both the fall and spring. Research, however, has

shown that light grazing of the winter rosette can

actually increase stooling and grain yield.

Conduct spring planting in

as short a time as possible. This may reduce the length

of time that area crops are vulnerable in the fall and

allow harvesting in the shortest time possible. Delay

fall plowing as long as possible in areas where

waterfowl damage standing or swathed grains. Waterfowl

can be encouraged to feed in the stubble, away from

unharvested crops, by using harvested fields as

field-baiting sites (see Alternate Food Sources below).

Recent research indicates

that geese prefer certain grass species over others for

food. Bluegrass (Poa spp.) is one of the most preferred,

and tall fescue (Festuca arundinaceae) is one of the

least preferred. Plant tall fescue instead of bluegrass

to reduce goose grazing in golf courses, parks, or

cemeteries. Plant trees to interfere with the birds’

flight paths and plant shrubs to reduce the birds’

on-ground visibility.

Alternate Food Sources.

Waterfowl damage to crops can be reduced by providing

alternate food sources in the form of lure crops or

direct feeding. For maximum benefit, an established and

well-organized program should be in place.

Lure crops are typically

grains that are used to attract and hold waterfowl,

thereby protecting other crop areas. Two general

strategies are used in establishing lure crop areas: (1)

seeding selected areas known to have a high incidence of

waterfowl damage with the specific intent of allowing

the birds to utilize the lure crop; (2) allowing the

birds to select a lure crop field and then paying the

landowner for the resulting loss.

Plant lure crops using

local crop(s) most subject to waterfowl damage. Plant at

the normal rate when using good quality seed. Increase

the normal planting rate by a factor of 1.5 to 2 when

using commodity grain or out-of-date seed to offset

reduced germination rates. Do not allow any hunting or

harassment of waterfowl in the lure crop area until all

crops are harvested and the damage season is over.

Field baiting involves

scattering grain in previously harvested fields or at

natural waterfowl feeding and/or loafing areas to

attract and hold waterfowl away from unharvested fields.

Studies in North Dakota indicate that the most effective

diversion of waterfowl occurs when the bait is made

available within 2 to 3 days of the birds’ first feeding

in an area. There are no set rules about the amount or

type of bait to use. Make enough bait available to

ensure that none of the birds go away hungry. If the

birds cannot get enough to eat at the baiting site, they

will go elsewhere. The bait grain should be something

the birds are familiar with and prefer. The same

material that is grown in the field should work well. Do

not allow any harassment of waterfowl in the area of the

baited field until all crops are harvested and the

damage season is over.

Surplus grain to conduct

these feeding programs can be obtained from the

Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC). People interested in

obtaining CCC grain for use in waterfowl damage

abatement programs should contact personnel from their

local US Fish and Wildlife Service regional office. CCC

surplus grain may only be used for the direct feeding of

depredating waterfowl or for seeding waterfowl feeding

areas. It may not be used to replace grain lost to

depredating waterfowl.

Regardless of the method

used (lure crop or field baiting), it may be necessary

to initially scare or herd the waterfowl away from the

surrounding fields. Once the birds have habituated to

the feeding site, and damage has stopped, repelling

efforts can be reduced.

Federal law requires that

all artificial feeding be stopped and all grain be

removed at least 10 days before hunting waterfowl within

the zone of influence of the baited area (50 CFR

20.21i).

Frightening

Waterfowl may be repelled by almost any large

foreign object or mechanical noise-making device placed

in a field. The length of time frightening devices are

effective depends on the nature, number, and variety of

devices used. Move frightening devices every 2 to 3 days

and use them in varying combinations to improve efficacy

and prevent habituation. Repellents should be in place

before the start of the damage season to prevent

waterfowl from establishing a use pattern.

Visual repellents such as

flags, balloons, and scarecrows are normally used at one

per 3 to 5 acres (1.2 to 2 ha) before waterfowl become

accustomed to loafing or feeding in the area. After the

birds become accustomed to using an area, one or more

per acre (0.4 ha) may be necessary. Visual repellents

should be reinforced with audio repellents such as

automatic exploders, pyrotechnics, or distress calls for

optimum results.

All applicable state and

local laws must be observed when using frightening

devices. Pay particular attention to laws governing the

making of loud noises, discharging of firearms, use of

pyrotechnics, and use of free-running dogs. Also

consider the possible reaction of neighbors.

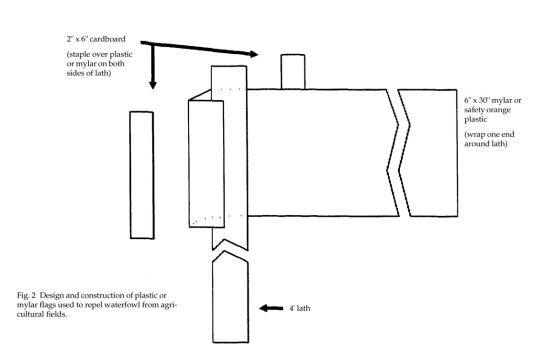

Flags for repelling

waterfowl can be made with 4-foot (1.2-m) laths and 6 x

30-inch (15 x 76-cm) strips of 3-mil safety orange

plastic or red and silver mylar ribbon (Fig. 2). Tests

conducted at Audubon National Wildlife Refuge indicate

that black flags are not effective. Place flags so they

are visible by waterfowl from all points in a field.

Waterfowl will land in an area where flags are not

visible. Once the birds land in a field with flags and

begin feeding, the flags’ effectiveness may be lost.

Balloons

filled with helium, staked in open fields or over water,

have proven to be effective waterfowl repellents. Tether

the balloons with enough 75-pound (34-kg) test

monofilament line to allow them to rise at least 10 feet

(3 m) into the air. The use of balloons larger than 2

feet (0.6 m) in diameter is not recommended due to their

increased wind resistance. Balloons with large

contrasting eye spots seem more effective than balloons

without eye spots. Balloons

filled with helium, staked in open fields or over water,

have proven to be effective waterfowl repellents. Tether

the balloons with enough 75-pound (34-kg) test

monofilament line to allow them to rise at least 10 feet

(3 m) into the air. The use of balloons larger than 2

feet (0.6 m) in diameter is not recommended due to their

increased wind resistance. Balloons with large

contrasting eye spots seem more effective than balloons

without eye spots.

Scarecrows can be made out

of almost any material available. Three concepts should

be incorporated into any scarecrow design: movement,

bright colors, and large eyes. For maximum effect, the

arms and legs should readily move in the wind.

Construction materials should be of bright colors such

as red, blaze orange, or safety yellow. Research

indicates that scarecrows with large eyes are more

effective than scarecrows with small eyes.

Mylar tape, 1/2 inch (11

mm) wide, has been used successfully to protect lawns,

crops, and other areas from bird damage. When properly

installed, mylar tape combines three control strategies

in one — overhead grids, sound repellents, and visual

repellents. Wind blowing over the tape will produce a

roaring sound as the tape twists and flashes, reflecting

the sunlight. Install the tape 1 to 3 feet (0.3 to 1 m)

above the area to be protected on 6-to 30-foot (2- to

10-m) centers. For a 100foot (30-m) span, the tape

should be twisted no more than 4 or 5 times before tying

it off. Over-twisting will reduce the flashing and

roaring effect. Mylar tape has a tendency to break at

the knot. This can be overcome by covering the last foot

(0.3 m) of the mylar with nylon strapping tape before

tying it off.

Water spray devices, using

high pressure, rotating, clapper-type sprinkler heads

have been used to repel other bird species from

reservoirs and fish raceways. Gulls have been repelled

from drinking water reservoirs by covering 50% of the

total water surface with the sprinklers and cycling them

on and off (5 minutes on and 35 to 45 minutes off)

during the daylight hours. Similar methodology may be

effective against waterfowl.

Automatic exploders, also

known as propane cannons, make a loud noise without

discharging a projectile. One exploder may protect up to

25 acres (10 ha) under ideal conditions. The rate of

firing is manually adjustable; exploders should be set

to fire about every 5 to 10 minutes. Reduce waterfowl

habituation and increase the effectiveness of exploders

by mounting them on turntables so the cannon rotates a

few degrees with each firing. Turn exploders off after

dusk and on at dawn to reduce neighbor complaints, bird

habituation, and save on fuel. Clock timers or

photocells are available for this purpose. Waterfowl may

use fields on bright moonlit nights. When they do, it

may be desirable to run exploders all night.

Pyrotechnics such as

shellcrackers, whistle bombs, screamer/banger rockets,

and noise bombs can be used to repel depredating

waterfowl. These devices should be fired to explode in

the air just over the birds to produce the greatest

scaring effect and reduce the fire hazard. Allowing

pyrotechnics to explode on the ground could ignite dry

grass or weeds. Refer to Bird Dispersal Techniques for

additional information.

Recorded distress calls

have been used to repel several species of nuisance

birds. Canada goose distress call tapes are not

commercially available as of this writing. Individuals

have made their own Canada goose distress call

recordings and have successfully repelled nuisance

geese.

Dogs trained to chase

waterfowl have been used to protect golf courses and

grain fields. Depending on the location and situation,

dogs can be free running, on slip-wires, tethered, or

under the control of a handler.

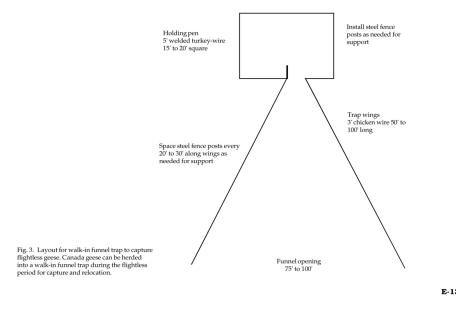

Fig. 3. Layout for walk-in

funnel trap to capture flightless geese. Canada geese

can be herded into a walk-in funnel trap during the

flightless Funnel opening 75' to 100' period for capture

and relocation.

Live

Capture Live

Capture

Local concentrations of

problem waterfowl can be reduced by live trapping. The

final disposition of trapped birds should be agreed upon

in advance by all relevant state and federal agencies.

The trapping method to use will depend on the type of

birds and the location of the problem. Secure a federal

permit before carrying out live capture activity (50 CFR

21.41a).

Walk-in funnel traps (Fig.

3) are the most effective traps for capturing Canada

geese in late June or early July, when the adult birds

are molting and have lost the ability to fly, and the

goslings have not yet fledged. The traps also work well

for feral ducks and geese in parks and similar

locations.

Set up the trap next to a

lake or pond being frequented by the birds. When

possible, place the trap in the area where the geese

normally walk in and out of the water. In situations

where there is no lake or pond, place the trap in a

large open area.

Construct a walk-in funnel

trap using the following, or similar materials:

-

100 to 200 feet (30 to

60 m) of 3-foot (1-m) poultry wire (for the trap

wings).

-

60 to 80 feet (18 to

24 m) of 5-foot (1.5-m) woven-wire fencing (for the

holding pen).

-

21, 5-foot (1.5-m)

steel fence posts to support the fencing.

-

Netting to cover the

top of the holding pen if the geese are to be held

several hours or overnight.

Once the trap is

constructed, herd the geese into it using boats, and/or

people walking on land. The exact number of boats and

people needed depends on the size of the area and the

number of geese. Gasoline-powered boats are not

recommended because they are too noisy. Canoes,

rowboats, or boats with electric trolling motors work

best. Surround the geese on three sides, leaving the

only avenue of escape towards and into the trap. Once in

position, slowly and quietly drive the geese into the

trap opening (Fig. 4) and into the holding pen. From

there, load the birds into suitable transport equipment

(such as turkey crates and covered pickup trucks) for

final disposition. When handling birds, wear eye

protection and long-sleeved shirts to avoid getting hit,

scratched, or pecked.

Fig. 4. Herding geese into

a walk-in funnel trap.

Rocket or cannon nets,

typically 25 x 50 feet (8 x 24 m) can be used to capture

waterfowl. Nets with 1-to 1.5-inch (2.5-to 3.8-cm) mesh

work well for ducks; 2- to 2.5-inch (5- to 6.3-cm) mesh

is best for large geese. Place the net at a baiting site

located close to water and bait the site with corn or

other suitable bait until the bait is well accepted.

Once the target birds are trained to feed at the bait

site, capturing them is merely a matter of re-baiting

the area, allowing the birds to concentrate on the bait,

then firing the rockets or cannons that carry the net

over the birds. Remove the trapped birds from the net as

quickly as possible. Place the birds in suitable

transport equipment (chicken crates, turkey crates) and

take them to the predetermined location.

Spring-powered nets, about

half the size of a standard rocket or cannon net (16 x

25 feet or 4.9 x 7.6 m), are available. They can be

triggered manually or electronically. One manufacturer

claims a closure time of less than 0.75 seconds using

No. 3 mesh netting, and 1.5 seconds using No. 6 mesh

netting.

Spring-powered netting's

quiet operation and the absence of explosive and flying

projectiles may, in some situations, be an advantage

even with the net’s small area.

Net launchers use a single

large rifle blank cartridge to propel the net. They are

fired from the shoulder much like a shotgun or rifle.

Net launchers are available in two styles: wide angle

for launching a 20 x 20-foot (6 x 6-m) net, designed for

air-to-ground helicopter capture, and narrow angle for

launching a 12 x 12-foot (3.6 x 3.6-m) net, designed for

ground-to-ground capture. The smaller net launchers are

well suited for capturing individual or small groups of

problem birds.

Alpha-chloralose is an

immobilizing agent that depresses the cortical centers

of the brain. Waterfowl fed about 30 mg of alpha-chloralose

per kg of body weight become comatose in 20 to 90

minutes. Full recovery occurs 4 to 24 hours later.

Alpha-chloralose is best suited for capturing individual

or small groups of problem waterfowl in situations or at

times when other methods are not safe or practical.

The US Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) has approved alpha-chloralose as an

immobilizing agent for the USDA-APHIS-ADC program to use

in the capture of waterfowl, coots, and pigeons. This

use is granted exclusively to ADC under a continuing

Investigational New Animal Drug (INAD) application.

Alpha-chloralose may only be obtained from the Pocatello

Supply Depot for use as an avian wildlife immobilizing

agent. Alpha-chloralose may only be used by ADC

employees or biologists of other state or Federal

wildlife management agencies that have been certified in

its use, or persons under their direct supervision.

Repellents

There are no chemical repellents currently

registered with the US Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) for controlling waterfowl. Several chemicals that

have shown taste or olfactory repellent properties,

including methyl anthranilate, are currently being

studied by USDA-APHIS-ADC Denver Wildlife Research

Center and other agencies.

Toxicants

There are no toxicants currently registered with EPA

for controlling waterfowl.

Shooting

Hunting, where safe and legal, is the preferred

method of reducing local populations of problem

waterfowl. Hunting has a strong repellent effect as

well. State wildlife management agencies can provide

information on current waterfowl hunting regulations.

In situations involving

real and direct threats to human health and safety, such

as geese around an airport, it may be possible to obtain

a permit from the US Fish and Wildlife Service to kill

migratory game birds. “Such birds may only by killed by

shooting with a shotgun not larger than No. 10 gauge

fired from the shoulder, and only on or over the

threatened area or areas” (50 CFR 21.42a). Such permits

are generally issued only when the use of nonlethal

control methods is not practical or possible. A solid

rationale as to why nonlethal methods will not work and

why the birds must be removed is generally required

before a permit to kill migratory game birds is issued.

Other Methods

The growth of local waterfowl populations can be

effectively slowed by destroying nests and eggs. This

method is especially effective with nuisance Canada

geese. Secure a federal permit before carrying out this

activity (50 CFR 21.41a).

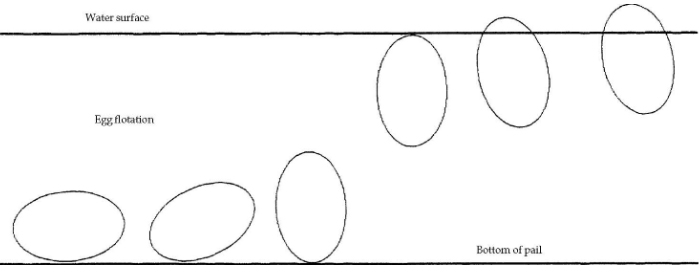

Render eggs nonproductive

by vigorously shaking them as soon as possible after the

full clutch is laid and incubation begins. The longer

incubation continues, the more difficult it becomes to

destroy the embryo by shaking. It is safe to assume that

the clutch is complete and incubation has started if the

eggs feel warm. In situations where the start of

incubation is unknown, eggs can be aged using the

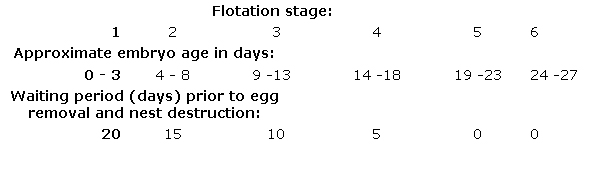

flotation method (Fig. 5).

Eggs in flotation stage 6

may be on the verge of hatching. If pipping has started,

the eggs should not be shaken, as shaking will probably

only accelerate hatching. Also, the US Fish and Wildlife

Service, Region 3 Law Enforcement, has taken the

position that a pipped egg contains a live bird, not an

embryo. Live birds may not be killed under authority of

an egg destruction permit.

After shaking the eggs,

return them to the nest, and allow the birds to incubate

for at least 3 weeks. The eggs and nest should not be

destroyed immediately after shaking. Doing so may cause

the geese to renest. Usually geese will not attempt to

renest if they have been incubating eggs for more than 3

weeks. Remove all nest materials and eggs from the area

after the appropriate waiting period. The nest and eggs

must be removed to discourage continuation of the

nesting effort and defense of the nest territory.

Most nest/egg destruction

permits do not authorize possession of waterfowl nests

or eggs. Therefore, all eggs and nest materials

collected under authority of such a permit must be

disposed of immediately.

Fig. 5. Age embryos by

placing 3 or 4 eggs in a pail of water and determining

the flotation.

Economics of Damage and Control

Waterfowl cause

significant losses to agricultural and aquacultural

crops, damage golf courses, cemeteries, lawns, and

gardens, and contaminate reservoirs. Their activities

can cause real economic hardship, aggravate nuisance

situations, or create human health hazards. A reliable

figure for the total national economic loss caused by

waterfowl does not exist. The following examples serve

to illustrate the magnitude of the problem, however.

In 1960, waterfowl caused

an estimated $12.6 million worth of damage to ripening

small grains on the Canadian prairies. In 1980,

waterfowl were credited with causing $454,000 worth of

damage to small grains in North Dakota, South Dakota,

and Minnesota combined.

The 1989 appraised crop

losses due to goose damage totaled $105,000 in the four

Wisconsin counties surrounding Horicon Marsh National

Wildlife Refuge (NWR). It is estimated that in the

autumn of 1989 over 1 million interior Canada geese

passed through Horicon Marsh NWR. This area has one of

the largest and most active goose damage abatement

programs in the country, with an annual budget of more

than $135,000.

Goose damage to golf

courses is difficult to quantify. A survey in 1982 of

219 golf courses in the eastern United States, however,

indicated that 26% had nuisance Canada goose problems.

It is not uncommon for geese to cause $2,000 to $3,000

damage per year to a golf course. Two golf course

superintendents in the greater Cleveland, Ohio, area

estimated that Canada geese caused between $2,000 and

$2,500 worth of property damage to each of their courses

in 1989. Three other golf course superintendents, in the

same geographic area, estimated that they spend $1,000 a

year just cleaning up Canada goose droppings, exclusive

of any direct property damage.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Richard A.

Dolbeer and Paul P. Woronecki of the USDA-APHIS-ADC

Denver Wildlife Research Center, and Douglas A. Andrews,

Ohio USDA-APHIS-ADC, for their editorial assistance in

the preparation of this manuscript.

Figure 2 adapted from

Duncan (1980).

Figure 4 photo by T. W.

Seamans.

Figure 5 adapted from

Westerkov (1950).

For Additional Information

Bellrose, F. C. 1980. Ducks, geese, and swans of North

America, 3d ed. Stackpole Books, Harrisburg,

Pennsylvania. 540 pp.

Conover, M. R. 1991.

Reducing nuisance Canada goose problems through habitat

manipulation. Proc. Great Plains Wildl. Damage Conf.

10:146.

Conover, M. R., and G. C.

Chasko. 1985. Nuisance Canada goose problems in the

eastern United States. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 13:228-233.

Cross, D. H.. 1987.

Deterring waterfowl from contaminated areas. US Dep.

Inter. Fish Wildl. Serv. Office of Information Transfer,

Region 8. 19 pp.

Duncan, M. J. 1980. The

use of plastic flags for controlling waterfowl damage in

small grains. US Dep. Inter. Fish Wildl. Serv. Leaflet.

Bismarck, North Dakota. 1 pp.

Emigh, F. D. 1962. Open

reservoir bird protection. J. Amer. Water Works Assoc.

54:1353-1360

Johnsgard, P. A. 1968.

Waterfowl: their biology and natural history. Univ.

Nebraska Press. Lincoln, 138 pp.

Knittle, C. E., and R. D.

Porter, 1988. Waterfowl damage and control methods in

ripening grain: an overview, US Dep. Inter. Fish Wildl.

Serv. Fish Wildl. Tech. Rep. 14. 17 pp.

National Archives and

Records Administration. 1992. Code of Federal

Regulations, Title 50, Parts 1 to 199, Wildl. Fish.,

Washington, DC. 615 pp.

Terry, L. E. 1984. A wire

grid system to deter waterfowl from using ponds on

airports. in Bird hazards at airports, prepared for the

Fed. Aviation Admin. by the US Dep. Inter. Fish Wildl.

Serv., Denver Wildl. Res. Center, Task H -DWRC Work Unit

904.33. 19 pp.

Westerkov, K. 1950.

Methods for determining the age of game bird eggs. J.

Wildl. Manage., 14:56-67.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom; Robert

M. Timm; Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

01/09/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|