|

|

|

|

|

BIRDS: Swallows |

|

|

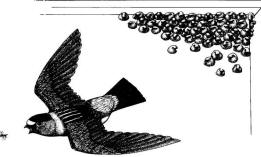

Fig. 1. Cliff swallow (Hirundo

pyrrhonota) with nests on a building

Identification

Eight members of the

swallow family Hirundinidae breed in North America: the

tree swallow (Tachycineta bicolor), violet-green swallow

(Tachycineta thalassina), purple martin (Progne subis),

bank swallow (Riparia riparia), northern rough-winged

swallow (Stelgidopteryx serripennis), barn swallow (Hirundo

rustica), cave swallow (Hirundo fulva), and the cliff

swallow (Hirundo pyrrhonota). Of the eight species, barn

and cliff swallows regularly build mud nests attached to

buildings and other structures, a habit that sometimes

puts them into conflict with humans. This is

particularly true of the cliff swallow, which nests in

large colonies of up to several hundred pairs. Barn

swallows tend to nest as single pairs or occasionally in

loose colonies of a few pairs. Some homeowners consider

barn swallows to be at most a minor nuisance. Many

homeowners tolerate nesting barn swallows as pleasant

and interesting summer companions around the home. This

chapter will focus on cliff and barn swallows because of

their close association with humans. The cliff swallow,

5 to 6 inches (13 to 15 cm) in length, is the only

square-tailed swallow in most of North America (Fig. 1).

It is recognized by a pale, orange-brown rump, white

forehead, dark, rust-colored throat, and steel-blue

crown and back. The cave swallow is similar in

appearance, but has a rust-colored forehead and pale

throat; it is restricted to southeast New Mexico and

central, south, and west Texas.

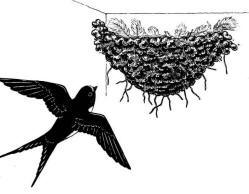

The barn swallow, 5 3/4 to

7 3/4 inches (15 to 20 cm) in length, is the only

swallow in the United States with a long, deeply forked

tail (Fig. 2). Barn swallows have steel-blue plumage on

the crown, wings, back, and tail. The forehead, throat,

breast, and abdomen are rust colored. Females are

usually duller colored than the males.

Range

Cliff and barn swallows

are found throughout most of North America. Breeding

occurs northward to Alaska and the Yukon, across Canada,

throughout the western United States, and south into

Mexico. Barn swallows are common nesters in most of the

southern United States, except Florida. Until recently,

cliff swallows did not breed in the southern United

States east of central Texas and south of west-central

Tennessee or western Kentucky. Reports of new colonies

in eastern Tennessee, Louisiana, Alabama, Arkansas,

Mississippi, and Florida suggest a range expansion into

the southern Atlantic seaboard and Gulf Coast states.

Barn swallows are also found in Europe, North Africa,

and Asia.

Fig.

2. Barn swallow with open, cup-shaped nest lined with

feathers. Fig.

2. Barn swallow with open, cup-shaped nest lined with

feathers.

Habitat

Four basic conditions are

found near most cliff and barn swallow nest sites:

(1) an open habitat for

foraging, (2) a suitable surface for nest attachment

beneath an overhang or ledge, (3) a supply of mud of the

proper consistency for nest building, and (4) a body of

fresh water for drinking.

The original nesting sites

of cliff swallows were cliffs and walls of canyons and

vertical banks, usually along permanent streams. Human

structures (for example, buildings, bridges) and

agricultural-related activities (irrigation, canals,

reservoirs) have increased the number and distribution

of suitable nesting sites, and cliff swallow populations

have increased accordingly. Historically, cliff swallows

were presumed to be most common in the western

mountains. They spread eastward following human

settlement and development of eastern North America.

The preferred habitat of

barn swallows includes open forests, farmlands, suburbs,

and rural areas with buildings that provide nest sites.

Like cliff swallows, barn swallows have benefited from

human activities. Their nests, originally built on

cliffs or in caves and crevices, are now built on beams

or walls of buildings or other structures. The presence

of livestock and power lines for perching are features

commonly associated with barn swallow nest sites.

Food Habits

All swallows are

insectivores, catching a variety of insects. Stomachs of

375 cliff swallows and 467 barn swallows collected in

different areas of the country contained prey from the

following orders: Hymenoptera (bees, wasps, and ants)

29%, 23%; Coleoptera (beetles) 27%, 16%; Hemiptera (true

bugs) 26%, 15%; and Diptera (flies) 13%, 40% for cliff

and barn swallows, respectively.

Cliff swallows may forage

over areas up to 4 miles (6.4 km) away from the nest.

They forage as a loose unit, and adults may be away from

the colony for hours prior to the hatching of young.

After the young hatch, a more or less steady stream of

adults return to the colony with food for the nestlings.

Barn swallows will fly

several miles from the nest site to suitable foraging

areas. Long periods of continuous rainfall make it

difficult for adult barn and cliff swallows to find

food, occasionally causing nestling mortality.

General

Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Migration

Cliff and

barn swallows winter in South America. They begin a

northward migration in late winter and early spring

overland through Central America and Mexico. Swallows

migrate during the day and catch flying insects along

the way. They will not penetrate regions unless flying

insects are available for food, which occurs after a few

days of relatively warm weather, 60 to 70oF (16 to 21oC)

or more. Arrival dates can vary greatly with weather

conditions. In general, cliff and barn swallows enter

the southern United States in mid-March to mid-April and

reach the northern portions of their range by early

June.

Site Selection

Swallows

have a homing tendency toward previous nesting sites.

Under suitable conditions, a nest is quite durable and

may be used in successive years. Most cliff swallows

arrive at a particular colony within a 24-hour period.

At large colonies, swallows may arrive in successive

waves. Resident adults are the first to return, followed

by adults who bred at other colonies, and by young

swallows who have not yet bred. The younger swallows

include individuals not born at the selected colony.

Swallow nests are

inhabited by hematophagous (bloodsucking) insects and

mites. Swallow bugs (Oeciacus vicarius), most common in

cliff swallow nests, can spread rapidly by crawling from

nest to nest in a new colony or by clinging to the

feathers of adults. Infestations of swallow bugs and

mites reduce nestling growth rates and cause up to half

of all nestling deaths. Swallow bugs are able to survive

in unoccupied nests for up to 3 years without feeding

and await returning swallows in spring. In selecting a

nest site, cliff and barn swallows apparently assess

which nests are heavily infested with parasites and

avoid them. Cliff swallow colonies often are not

reoccupied after 1 or 2 years of use because of heavy

infestations. Cliff swallows will even prematurely

desert their nests en masse, leaving their young to

starve, when swallow bug populations become too great.

Nest Construction

Cliff

swallow nests are gourd-shaped, enclosed structures with

an entrance tunnel that opens downward (Fig. 1). The

tunnel may be absent from some nests. The mud pellets

used to build the nest consist of sand and smaller

amounts of silt and clay. The nest chamber is lined

sparingly with grasses, hair, and feathers. The nest is

cemented with mud under the eave or overhang of a

building, bridge, or other vertical surface. The first

cliff swallow nests on structures are usually located at

the highest point possible, with subsequent nests

attached below it, forming a dense cluster.

Barn swallow nests are

cup-shaped rather than gourd-shaped, and the mud pellets

contain coarse organic matter such as grass stems, horse

hairs, and feathers (Fig. 2). The nest cup is profusely

lined with grasses and feathers, especially white

feathers. Barn swallow nests are also typically built

under eaves or similarly protected sites but not

necessarily at the highest point possible. Barn swallows

often use a beam or the protruding edge of a door or

window jamb as the base for the nest, or attach the nest

at the juncture of the two walls of an interior corner.

Both male and female cliff

and barn swallows construct the nest, proceeding slowly

to allow the mud to dry and harden. Depending on mud

supply and weather, nest construction may take 1 to 2

weeks. Mud is collected at ponds, puddles, ditches, and

other sites up to 1/2 mile (0.8 km) away, with many

swallows using the same mud source. A typical cliff

swallow nest contains 900 to 1400 pellets, each

representing one trip to and from the nest.

Among cliff swallows, mud

gathering and nest construction are social activities;

even unmated swallows will start nests. Mated swallows

may build more than one nest per season, even though not

all will be used. A count of nests under construction

will not give an accurate estimate of the number of

breeding cliff swallows.

Egg Laying

Cliff

swallows usually begin laying eggs before the entrance

tunnel is completed. Each day 1 egg is laid until the

clutch, usually 3 or 4 eggs, is completed. In Texas, egg

laying may begin as early as late March to early April,

while in North Dakota nesting may not start until early

to mid-June. Within a large colony, the date of egg

laying varies due to the staggered arrival dates of the

swallows. For small colonies, laying may be more

synchronous.

Barn swallows typically

lay 4 or 5 eggs, but laying may be delayed for some time

after nest building is completed. The breeding season

begins in early April in the south to mid-June in the

northern portions of the range. Barn swallows are

double-brooded, resulting in a prolonged nesting season.

Nest Failures

Renesting

will occur if nests or eggs are destroyed. Nests may

fall because they were built too rapidly or crumble

because of prolonged humid weather or rain. House

sparrows (Passer domesticus) sometimes usurp empty

swallow nests and may also drive off swallows from new

nests. A cliff swallow nest taken over by house sparrows

is identified by the abundant nest lining (grasses,

weeds, feathers, and litter) protruding out of the

entrance tunnel. Cats associated with farm and other

buildings are common predators of barn swallows.

Hatching

Both sexes

incubate the eggs. Incubation begins before the last egg

is laid and ranges from 12 to 16 days for cliff swallows

and 13 to 17 days for barn swallows. Most studies report

incubation of 14 or 15 days. Whitewash on the ground

below the nest or on the rim of the nest entrance is a

sign of newly hatched nestlings inside the nest. This

marking occurs when adults remove fecal sacs from the

nest and later when nestlings defecate from the nest.

Fledging and Postnesting

Period

Cliff

swallow nestlings fledge 20 to 25 days after hatching;

barn swallows fledge in 17 to 24 days. The juvenile

swallows appear similar to adults but are dull colored

and have less sharply-defined color patterns. The

fledglings return to the nest each day for 2 to several

days to be fed before leaving it permanently. Within a

week, juveniles will join flocks and leave the area.

At least some cliff

swallows raise 2 broods in a breeding season. Second

broods are documented from Virginia and West Virginia

but are uncommon in central California. Late nests may

result from renesting attempts after a first failure, or

from late nesters. The time from start of nest building

to departure is 44 to 64 days: 7 to 14 days nest

building, 3 to 6 days egg laying, 12 to 16 days

incubation, 20 to 25 days to fledging, and 2 or 3 days

to leave the nest. Reports of colony occupancy ranging

from 110 to 132 days indicate ample time for 2 broods.

After leaving the nest,

swallows may remain in the general area for several

weeks. By late summer there is a general southward

movement, and by the end of September few swallows

remain in the nest site. Fall migration of swallows is

not well documented.

Damage

Cliff swallows nest in

colonies and often live in close association with

humans. Many swallow colonies on buildings and other

structures are innocuous. In some situations, however,

they can become a major nuisance, primarily because of

the droppings they deposit. In such instances they may

create aesthetic problems, foul machinery, and cause

health hazards by contaminating foodstuffs. Their mud

nests eventually fall to the ground and can cause

similar problems. Parasites found in swallow nests,

including swallow bugs, fleas, ticks, and mites, may

bite humans and domestic animals, although these are not

the usual hosts. In addition, cliff swallow nests are

often used by house sparrows, introducing another avian

pest and its attendant damage problems and potential

health hazards.

Barn swallows nesting

singly or in small groups on a structure can cause

similar problems but of a lesser magnitude due to the

smaller numbers present.

Legal Status

In the United States, all

swallows are classified as migratory insectivorous birds

under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. Swallows

are also protected by state regulations. It is illegal

for any person to take, possess, transport, sell, or

purchase swallows or their parts, such as feathers,

nests, or eggs, without a permit. As a result, certain

activities affecting swallows are subject to legal

restrictions.

Permit Requirements

A depredation permit

issued by the US Fish and Wildlife Service may be

required to remove swallow nests. Three of seven

administrative regions of the US Fish and Wildlife

Service in the continental United States require a

permit regardless of the time of year. This includes

nests under construction, completed but empty nests,

nests with eggs or young, or nests abandoned after the

breeding season. Four of the seven regions do not

require a permit if eggs or young birds are not present

in the nest.

If eggs or nestlings are

present, a permit authorizing nest removal or the use of

exclusion techniques is required in every region and

will be issued only if very compelling reasons exist. An

example might be the safety hazard of a nesting colony

located at an airport where aircraft safety is in

question and where other methods of control are not

applicable. In most cases (for example, swallows nesting

on a residence or other building), a permit allowing

lethal control will not be issued.

For permit requirements in

your area, contact the closest US Fish and Wildlife

regional office or USDA-APHIS-ADC district office. At

the first sign of nest building, contact the appropriate

authorities, since swallows can build their nests and

lay eggs in a short time. Timing is critical in those

regions that require a permit. If a swallow problem has

been experienced in the past at a site and is expected

to reoccur, then apply for a permit in advance of the

birds’ return. A fee is charged for a permit.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Exclusion

refers to any control method that denies a bird physical

access to a nest site. Exclusion represents

a relatively permanent, long-term solution to the

problem. A permit is not required for this method except

when eggs or young are in the nest.

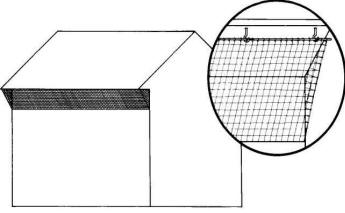

Plastic net or poultry

wire can provide a physical barrier between swallows and

a nest site. Mesh size should be about 3/4 inch (1.9

cm); however, 1inch (2.5-cm) mesh has been used

successfully. If plastic net is used, it should be taut

to reduce flapping in the wind, which looks unsightly

and results in tangles or breakage at mounting points.

Do not use mist net or any other thin, flexible net with

loose pockets or wrinkles that could trap or entangle

swallows. For best results, install net or poultry wire

before the swallows arrive. It may be left up

permanently or removed after the nesting season.

Attachment methods may

vary according to site requirements and the degree of

permanence desired. Net can be attached using tape,

staples, velcro, trash bag ties, or plastic fasteners

such as zip ties or polyclips. Polyclips are a useful

aid for installing netting. They snap together through

the netting strands and allow the use of nails, screws,

or wire for attachment. A more elaborate method uses

hooks, such as brass cup hooks, mounted on wooden eaves

and the sides of buildings. An advantage of hooks or

velcro is that the net can be taken down easily during

the nonbreeding period or for painting or maintenance of

light fixtures. If hooks or staples are used, they

should be rust-resistant to avoid unsightly rust stains.

For net, a supporting framework of wooden dowels along

the edges can ease attachment to the hooks and create a

more equal tension on the net (Fig. 3). Net may also be

stapled to or wrapped once or twice around wood laths,

which are then nailed directly to the structure. On a

concrete or cement structure, a power-activated tool,

sometimes called a stud gun, can be used to nail the

wood lath. The net or wire should extend from the outer

edge of the eave down to the sides of the building so

the eaves no longer provide swallows with protection

from the elements (Figs. 3 and 4). No openings should

remain where swallows might enter. Hanging a curtain of

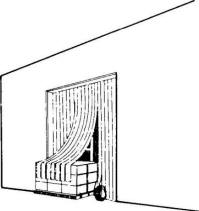

netting from eaves is reported effective (Fig. 4). The

curtain should be 3 to 4 inches (8 to 10 cm) from the

wall and extend down from the eave 18 inches (46 cm) or

more. For barn swallows the net or wire should be

extended down further than for cliff swallows to cover

door and window jambs and to block off interior corners.

Usually, swallows will not

fly into a net or other obstruction, but will stop and

hover in front of it. If only that section of a building

where swallows have nested is netted, the swallows will

often choose alternative sites on the same structure.

Therefore, any part of a building suitable for nesting

must be netted.

Barn swallows frequently

and cliff swallows occasionally enter buildings through

doors or other open entryways and nest inside among the

rafters. In some instances simply closing the entrance

or blocking it with net or wire is practical and

effective. At one site, cliff swallows abandoned nests

inside barn lofts when entrance ways were partially

closed. At warehouses and other buildings with frequent

pedestrian or equipment passage, opening and closing an

entrance way may be bothersome and impractical. In these

situations strip doors of vinyl plastic may be installed

(Fig. 5). Strip doors consists of 6- to 16inch (15- to

41-cm) wide strips of vinyl hung like a curtain and are

primarily used to control temperature in refrigerated

areas. Strips overlap about 2 inches (5 cm). Strip doors

do not require opening and closing like conventional

doors and are not damaged by passage of equipment. The

use of net hung as a curtain to block an entrance is

recommended only where there is no possibility of its

being caught and ripped by equipment. Weighting the

bottom of the net will help keep it reasonably taut and

in position during windy weather.

Barn swallows have been

repelled from nesting by clear monofilament line

attached under eaves. The lines were spaced 12 inches

(30 cm) apart and were in a parallel or zigzag pattern.

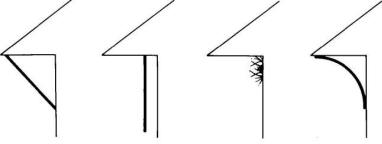

Habitat Modification

Substrate

Modification. Modification of the nest substrate has

proven effective. Swallows prefer surfaces that provide

a good foothold and nest attachment. Removal of the

rough surface of a wall and/or overhang makes a site

less attractive. This may be accomplished in various

ways. Fiberglass panels make nest attachment difficult

if installed between the eave and wall to form a smooth,

concave surface (Fig. 4). A smooth surface is also

created by a curtain of aluminum foil or plastic tarp

draped from a wire strung along the junction of the wall

and roof overhang. Other smooth-surfaced materials such

as glass, plexigass, or sheet metal can be used.

Fig. 3. Netting mounted on building from the outside

edge of the eave down to the side of the building.

Insert shows a method of attachment using hooks and

dowels.

Fig. 4. Four methods which may deter swallow nesting.

From left to right: Netting attached from the outer edge

of the eave down to the side of the building; a curtain

of netting; metal projections along the junction of the

wall and eave; fiberglass panel mounted to form a

smooth, concave surface.

Fig. 5. Strip doors of vinyl plastic allow passage of

equipment and exclude swallows and other birds.

A fresh coat of paint that

dries to a slick surface is sometimes effective. On

rough surfaces, painting is of doubtful value because it

does not alter the basic rough texture of the surface.

Painting may be effective on smoother surfaces, but this

technique has not been thoroughly tested.

Metal projections such as

Nixalite® and Cat Claws® are sharp, needle-like wire

devices generally installed on building ledges and

window sills to discourage pigeons and starlings from

roosting. Although adaptable to mounting and use under

eaves, metal spines have not been widely used for

swallow control (Fig. 4). In one instance, cliff

swallows learned to land on the metal spines and

eventually built nests attached to them.

Architectural Design.

Although all the factors that constitute a suitable

colony site are not yet understood or documented,

architectural design does influence colony site

suitability. Buildings with overhanging eaves at acute

to right angles with the wall are potential nest sites.

Conversely, sites where the overhang and wall meet at an

obtuse angle or are rounded and concave are rarely used.

The width of the overhang may be important to site

suitability, although the point at which this becomes

critical is unknown. Few colonies are observed with an

overhang of less than 6 to 8 inches (15 to 20 cm).

Substrate texture is a

factor; wood, stucco, masonry, and concrete surfaces are

favorable substrates for nest attachment. Metal is

rarely used as a nest substrate. Nests on metal surfaces

are usually located at a crotch or joint where the

swallow can gain a foothold. In situations where

construction is planned and swallows are present on

nearby structures, consideration to materials and design

may eliminate future problems. Swallows may move to

nearby structures if control is applied at an existing

colony.

Frightening

Hawk, owl, or

snake models; noisemakers; and revolving lights have

shown little, if any, success or are unproven against

swallows. As evidenced by nests in and on buildings,

barn and cliff swallows are relatively tolerant of human

activity and other disturbances.

Repellents

Chemical roost

repellents (polybutenes, sticky pastes, sprays) have not

been proven effective. Unless a suitable nesting site is

almost entirely covered with repellent, swallows will

still be able to land, gain a foothold, and begin nest

construction. A sticky repellent may actually be

counterproductive by improving nest adherence. Cliff

swallow nests built over a sticky repellent have been

observed. Since state pesticide registrations vary,

check with your local Cooperative Extension office for

information on possible repellents.

Toxicants, Trapping, and

Shooting

There are no

chemical toxicants currently registered by EPA for

swallow control, and shooting, trapping, or harming

swallows is not permitted.

Nest Removal

Nest removal

should be initiated at the first sign of nest building

because of the difficulty in obtaining a permit to

remove nests with eggs or young. Usually nests can be

washed down with a water hose or knocked down with a

pole. Removing nests by these methods is a messy and

time-consuming process and may cause dispersal of nest

parasites and water damage to the building.

As builders of mud nests,

swallows have evolved to persist despite nest failures

from rain or moisture. Washing down nests is nothing

more than an artificial rainstorm. Because swallows will

persistently rebuild nests, removal will be required for

several days during nest building. Persistence is

undoubtedly affected by the physiological condition of

the swallows, past nesting history at the site, and the

availability of alternate sites. The swallows may return

the following year, and unless additional control

measures are implemented, the whole process may need to

be repeated.

Leaving swallow nests

intact may be appropriate in some instances. For

example, if swallows have established a colony, raised

their young, and left, nest removal would also remove

nest parasites, thus improving the site for the swallows

returning the next spring. Swallow bugs will overwinter

in the nests, and if the parasite load is high in the

spring, the swallows might abandon the colony. If not,

they would probably reoccupy the nests. At the first

signs of reoccupancy, such as repair of old nests or

building of new nests, nest removal (with a permit in

some locations) should be started and continued until

the nesting attempts end.

Economics of Damage and Control

Costs of damage are

difficult to quantify and vary with the particular site

and the method of control employed. The cost of actual

or potential damage can range from the cleanup of

droppings on and around a structure, to thousands of

dollars from swallows contaminating foodstuffs at a

processing center or posing a danger to aircraft at an

airport. Similarly, control costs vary greatly. When

hosing is used, costs are primarily labor-related. Net

is relatively inexpensive (from about $9 to $33 per

1,000 square feet depending on quantity purchased, 1992

prices) and is reported to be effective for 4 to 5 years

before replacement is necessary. Labor and other

equipment costs to install netting, however, can be

quite high. For example, mounting net on a concrete

versus a wooden structure, or 100 feet (30 m) versus 10

feet (3 m) above the ground can drastically increase

costs. Costs for each site must be judged on an

individual basis.

Acknowledgments

Figures 1 through 5 by

Arlene Chin, Senior Artist, Visual Media, University of

California, Davis.

For Additional Information

Anon. 1981. Bird control problem solved with netting.

Pest Control 49:28-29.

Barclay, R. M. R. 1988.

Variation in the costs, benefits, and frequency of nest

reuse by barn swallows (Hirundo rustica). Auk 105:53-60.

Beal, F. E. L. 1918. Food

habits of the swallows, a family of valuable native

birds. US Dep. Agric. Bull. No. 619. 28pp.

Brown, C. R., and M. B.

Brown. 1986. Ectoparasitism as a cost of coloniality in

cliff swallows (Hirundo pyrrhonota). Ecol. 67:1206-1218.

Emlen, J. T., Jr. 1952.

Social behavior in nesting cliff swallows. Condor

54:177-199.

Emlen, J. T., Jr. 1954.

Territory, nest building, and pair formation in the

cliff swallow. Auk 71:16-35.

Emlen, J. T. 1986.

Responses of breeding cliff swallows to nidicolous

parasite infestations. Condor 88:110-111.

Erskine, A. J. 1979. Man’s

influence on potential nesting sites and populations of

swallows in Canada. Can. Field Nat. 93:371-377.

Johnsgard, P. A. 1979.

Birds of the Great Plains: breeding species and their

distribution. Univ. Nebraska Press, Lincoln. 539 pp.

Mayhew, W. W. 1958. The

biology of the cliff swallow in California. Condor

60:7-37.

Moller, A. P. 1990.

Effects of parasitism by a haematophagous mite on

reproduction in the barn swallow. Ecol. 71:2345-2357.

Pochop, P. A., R. J.

Johnson, D. A. Aguero, and K. M. Eskridge. 1990. The

status of lines in bird damage control—a review. Proc.

Vertebr. Pest. Conf. 14:317-324.

Samuel, D. E. 1971. The

breeding biology of barn and cliff swallows in West

Virginia. Wilson Bull. 83:284-301.

Speich, S. M., H. L.

Jones, and E. M. Benedict. 1986. Review of the natural

nesting of the barn swallow in North America. Am. Midl.

Nat. 115:248-254.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

E-128

01/09/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|