|

|

|

|

|

BIRDS: Sparrows, House |

|

|

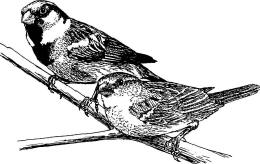

Fig. 1. House sparrow,

Passer domesticus. Male (left) and female (right).

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Block entrances

larger than 3/4 inch (2 cm).

Design new buildings or alter old ones to eliminate

roosting and nesting places. Install plastic bird

netting or overhead lines to protect high-value crops.

Cultural Methods

Remove roosting

sites. Plant bird resistant varieties.

Frightening

Fireworks, alarm calls, exploders. Scarecrows,

motorized hawks, balloons, kites. 4-Aminopyridine (Avitrol®).

Repellents

Capsicum. Polybutenes. Sharp metal projections (Nixalite®

and

Cat Claw®).

Toxicants

Fenthion in Rid-A-Bird® toxic perches.

Trapping

Funnel,

automatic, and triggered traps. Mist nets.

Shooting

Air guns and small firearms. Dust shot and BB caps.

Other Methods

Nest

destruction. Predators.

Identification

The house or English

sparrow (Fig. 1) is a brown, chunky bird about 5 3/4

inches (15 cm) long, and very common in human-made

habitats. The male has a distinctive black bib, white

cheeks, a chestnut mantle around the gray crown, and

chestnut-colored feathers on the upper wings. The female

and young are difficult to distinguish from some native

sparrows. They have a plain, dingy-gray breast, a

distinct, buffy eye stripe, and a streaked back. The

black bib and chestnut-colored feathers on the wings are

the first signs of male plumage and appear on the young

birds within weeks of leaving the nest.

Range

The house sparrow was

first introduced in Brooklyn, New York, from England in

1850 and has spread throughout the continent.

Habitat

The house sparrow is found in nearly every

habitat except dense forest, alpine, and desert

environments. It prefers human-altered habitats,

particularly farm areas. While still the most common

bird in most urban areas, house sparrow numbers have

fallen significantly since they peaked in the 1920s,

when food and wastes from horses furnished an unlimited

supply of food.

Food Habits

House sparrows are

primarily granivorous. Plant materials (grain, fruit,

seeds, and garden plants) make up 96% of the adult diet.

The remainder consists of insects, earthworms, and other

animal matter. Nestlings, however, are fed mostly animal

matter. Garbage, bread crumbs, and refuse from fast-food

restaurants can support sparrow populations in urban

habitats.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Breeding can occur in any

month but is most common from March through August. The

male usually selects a nest site and controls a

territory centered around it. Nests are bulky, roofed

affairs, built haphazardly and without the good

workmanship displayed by other weaver finches, the group

to which the house sparrow belongs. Sparrows are loosely

monogamous. Both sexes feed and take care of the young,

although the female does most of the brooding. From 3 to

7 eggs are laid, 4 to 5 being the most typical.

Incubation takes 10 to 14 days, and the young stay in

the nest for about 15 days. They may still be fed by the

adults for another 2 weeks after leaving the nest.

House sparrows are

aggressive and social, both of which increases their

ability to compete with most native birds. Sparrows do

not migrate. Studies have shown that 90% of the adults

will stay within a radius of 1 1/4 miles (2 km) during

the nesting period. Exceptions occur when the young set

up new territories. Flocks of juveniles and nonbreeding

adults will move 4 to 5 miles (6 to 8 km) from nesting

sites to seasonal feeding areas.

Mortality is highest

during the first year of life. Few sparrows survive in

the wild past their fifth season. One individual,

however, lived in captivity for 23 years. While house

sparrows are tolerant of disturbance by humans, they can

in no way be considered tame. Their success lies in

their ability to exploit new habitats, particularly

those influenced by humans.

Damage

House sparrows consume

grains in fields and in storage. They do not move great

distances into grain fields, preferring to stay close to

the shelter of hedgerows. Localized damage can be

considerable since sparrows often feed in large numbers

over a small area. Sparrows damage crops by pecking

seeds, seedlings, buds, flowers, vegetables, and

maturing fruits. They interfere with the production of

livestock, particularly poultry, by consuming and

contaminating feed. Because they live in such close

association with humans, they are a factor in the

dissemination of diseases (chlamydiosis, coccidiosis,

erysipeloid, Newcastle’s, parathypoid, pullorum,

salmonellosis, transmissible gastroenteritis,

tuberculosis, various encephalitis viruses, vibriosis,

and yersinosis), internal parasites (acariasis,

schistosomiasis, taeniasis, toxoplasmosis, and

trichomoniasis), and household pests (bed bugs, carpet

beetles, clothes moths, fleas, lice, mites, and ticks).

In grain storage

facilities, fecal contamination probably results in as

much monetary loss as does the actual consumption of

grain. House sparrow droppings and feathers create

janitorial problems as well as hazardous, unsanitary,

and odoriferous situations inside and outside of

buildings and sidewalks under roosting areas. Damage can

also be caused by the pecking of rigid foam insulation

inside buildings. The bulky, flammable nests of house

sparrows are a potential fire hazard. The chattering of

the flock on a roost is an annoyance to nearby human

residents.

Nestlings are primarily

fed insects, some of which are beneficial and some

harmful to humans. Adult house sparrows compete with

native, insectivorous birds. Martins and bluebirds, in

particular, have been crowded out by sparrows that drive

them away and destroy their eggs and young. House

sparrows generally compete with native species for

favored nest sites.

Legal Status

The house sparrow is

afforded no legal protection by federal statutes because

it is an introduced species. A few states, however, may

offer them some protection by requiring permits or

otherwise restricting control activities. Check with

state or local governments before poisoning or shooting

house sparrows.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Close all

openings over 3/4 inch (2 cm) to exclude house sparrows

from buildings. Replace the glass in broken windows or

cover them with plywood or wire mesh. Block openings,

like bell towers, with poultry mesh no larger than 3/4

inch (2 cm). Warehouse doorways that must accommodate

human traffic can sometimes be effectively blocked by

hanging a flexible wall of 4- to 6-inch (10-to 15-cm)

plastic strips in front of the opening. These will not

seriously impede human movements yet present an

impassable barrier to sparrows. Poultry houses and

feeders should be screened to exclude sparrows.

Attach signs flat against

buildings to avoid providing roosting sites. Screen or

block spaces between existing signs and buildings.

Install slanted metal, plexiglass, or wooden boards

(>45o angle) over ledges, such as those under shopping

mall overhangs or on old buildings, so sparrows cannot

roost or nest on them. Eaves should be screened if the

birds are able to squeeze into them. Block the spaces

between window air conditioners and buildings to keep

sparrows out. If possible, place fine mesh over

architectural decorations on old buildings to prevent

roosting. It is much more effective, however, to work

with architects on building designs that eliminate

ornamental patterns and holes that provide nest sites

for sparrows.

Prevent house sparrows

from roosting on ivy-covered walls by stringing plastic

bird netting (green or black) over the vines. While not

as satisfactory as removing the shrubbery, the mesh

generally blends in with the plants and still prevents

the birds from roosting and nesting in them. Place

netting in front of ventilator openings to keep birds

out of buildings. Examine ventilators, vents, air

conditioners, building signs, ledges, eaves, overhangs,

ornamental openings, and ornate designs for potential

and existing bird usage and eliminate those sites where

practical.

Protect small crop areas

with plastic bird netting in situations involving

high-value crops, such as grapes, berries, or

experimental grains. This approach can be economical if

netting is used for several years to protect the site.

Leave no openings at the bottom of netted crop areas.

Sparrows that get into fields through such openings and

are unable to find their way out can cause considerable

damage.

House sparrows can be

discouraged at bird feeders by installing vertical

monofilament lines at 2-foot (0.6-m) intervals around

the feeders. Studies have shown that many other species

of birds are not affected. Electric wires can be

installed on perches of feeders to shock house sparrows

when they land. This requires watching the feeder so the

current can be activated only when house sparrows are

attempting to feed.

House sparrows cannot use

bird houses with openings 1 1/8 inches or less (2.8 cm);

this size can be used only by wrens. Sparrows are

attracted to and often colonize martin apartment houses

if they are left unattended. Martin houses should be

placed on tall poles in an unobstructed air space

necessary for their aerial acrobatics. Block the

entrances to martin houses until martin scouts appear in

spring, back from their winter feeding grounds. Lower

and clean the houses at the end of the breeding season.

Bluebirds can be encouraged with nest boxes that have 1

1/2-inch (3.8-cm) entrance holes and a 3 1/2-inch (9-cm)

hole bored in the roof, covered with 1/2-inch (1.3-cm)

mesh. Bluebirds apparently can withstand wetting, but

the sparrows like a tight roof overhead.

Cultural Methods

Destruction of

roosting and nesting sites is one approach to solving a

sparrow problem. Total removal of shrubs or even trees

is an effective but extreme measure. In rural areas,

removal of hedgerows adjacent to crop fields will limit

the attractiveness of the area to house sparrows, but

will also have a negative effect on other wildlife.

Remove dead fronds from palm trees to eliminate roosting

sites.

Several varieties of small

grains are resistant to bird damage. Some sorghum

varieties have a high tannin content in the early growth

stages. Others have loose seed heads, on which sparrows

are unable to perch and feed.

Frightening

No truly

successful alarm or distress calls have been found for

house sparrows. Frightening devices designed for other

species (fireworks, shell crackers, acetylene exploders,

and cymbals) will move sparrows from an area for a short

period. Sparrows, however, adapt quickly to frightening

devices and will not be repelled by sounds for any great

length of time unless the sounds are diversified and

their locations shifted periodically.

Visual frightening devices

can be helpful in some areas where crops are susceptible

to damage for only a short period. Of the “scarecrow”

devices, kites, balloons, and simulated bird of prey

forms that circle above are the most useful. Sparrows

can be frightened temporarily by mylar tape or

shimmering foil strips. Alternate the use of several

audio and visual frightening devices for best control.

4-Aminopyridine (Avitrol®)

is registered as a chemical frightening agent because

the affected birds react so violently to it that the

remainder of the flock is frightened out of the treated

area. Usually large numbers of sparrows die before the

repellent effect is achieved.

Repellents

Spread tactile

repellents such as sticky bird glues on ledges to

prevent roosting. These polybutenes are reasonably

effective for periods of 1 year or more. They are messy

and should be placed on tape or sealed masonry surfaces

so they can be removed. They lose their tackiness after

they become hardened by changing weather or covered by

dust.

More expensive, but longer

lasting than chemicals, are sharp metal projections such

as Nixalite® and Cat Claw®. These sharp metal

projections prevent the birds from roosting comfortably

in an area. Sparrows can roost on ledges only 1 1/2

inches (3.8 cm) wide. Therefore, ledges and other niches

must be completely covered. Placing monofilament lines

at 1-to 2-foot (0.3- to 0.6-m) intervals may help to

repel house sparrows from roosting sites. Electrified

wires strung over roost sites have been effective, but

it is an expensive alternative.

Granular formulations of

capsicum are federally registered for repelling sparrows

from certain fruits, vegetables, and grain crops. Read

the product label for specific information.

Toxicants

Fenthion is the

only toxicant registered for controlling house sparrows.

It is applied by using Rid-A-Bird® perches. These metal

perches have a wick in the center that delivers the

liquid toxicant to the feet of birds as they perch. The

habits of the birds in individual situations must be

studied to determine the most effective placement of the

perches. This is an effective and reasonably selective

method when used inside buildings. Use extreme care to

avoid spillage of the toxicant. Fenthion can be absorbed

through the skin, so applicators must be aware of the

toxicity hazards.

State pesticide

registrations vary. Check with your local extension or

USDA-APHIS-ADC office for information on toxicant and

repellent use in your area.

There are no fumigants

registered for use against sparrows.

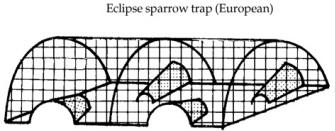

Trapping

Trapping is

probably the most widely used method in attempting to

reduce house sparrow populations in a small area. As

most bird traps normally are live traps, nontarget

species can be released unharmed. There are more types

of traps available for sparrows than for any other bird.

Sparrows that have been trapped once often become

trap-shy. Therefore, traps alone are insufficient to

remove an entire sparrow population.

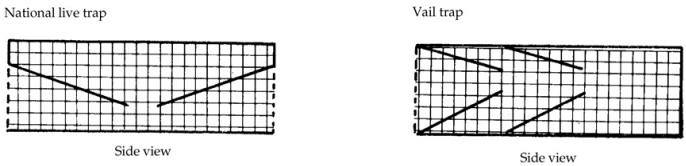

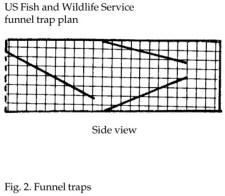

Funnel Traps. These are

the most commonly used traps available (Fig. 2). While

funnel traps are probably the most easily entered of any

trap, sparrows can also escape from them with relative

ease. Thus, they should be checked frequently and the

birds removed. Where possible, decoy individuals should

be penned in separate compartments inside these traps

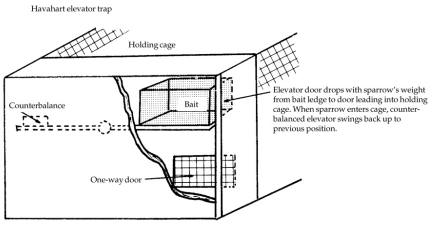

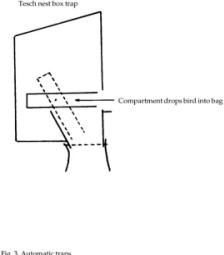

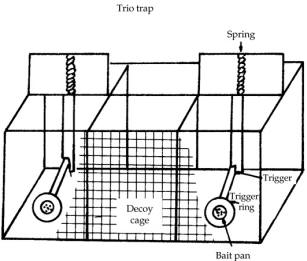

Automatic Traps. These are

counterbalanced multicatch traps (Fig. 3). House

sparrows enter a compartment alone to feed on bait that

is placed on a shelf in the trap. Their weight causes an

“elevator” to drop to the lower level where the bird

“escapes” into a closed cage. Without the bird’s weight,

the counterbalanced “elevator” springs back into the

original position ready for another passenger. It is

more difficult to entice the birds into this type of

trap than into the funnel traps, but the final catch is

probably greater as it is almost impossible for the

sparrows to escape.

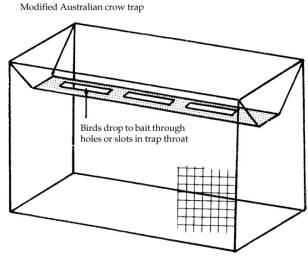

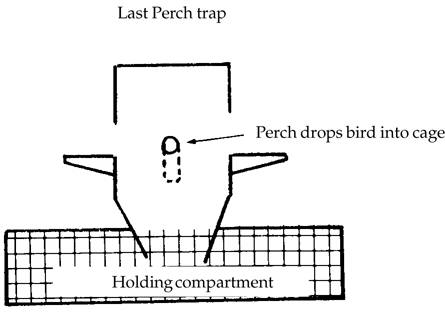

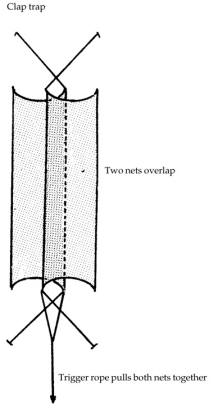

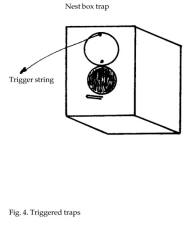

Triggered Traps. These

traps are limited by the number of house sparrows they

can catch at one time (Fig. 4). In some cases the traps

are not automatic and consequently require a watcher to

tend them and spring them at the proper moment. The

“clap trap” is one of the oldest bird traps, used first

by ancient Egyptians.

Mist Nets. A final method

of trapping is to entangle flying house sparrows in a

fine net known as a mist net. Mist nets are placed

across the flight paths of the birds in front of a dark

background. The nets cannot be seen until the birds

blunder into them, become entangled, and are unable to

extricate themselves. Mist nets also require

considerable amount of time to set up and tend, and they

are illegal in some states. Federal permits are required

for trapping birds in mist nets. Nontarget species may

be captured and must be removed and released

immediately.

Shooting

Shooting with

air guns or low-powered firearms can be used with some

success where local ordinances permit. Sparrows quickly

become wary of a human holding anything resembling a

firearm, so shooting from a blind is recommended

whenever possible. An old method is to place grain in a

windrow and shoot into a baited flock with an open-choke

shotgun. Special ammunition known as “dust shot” (a .22

long rifle shell filled with No. 10 shot) or “BB caps”

(a lead slug in a short .22 shell) are available. The

effective range of these specialized tools, however, is

extremely limited.

Other Methods

Nest

Destruction. Discourage house sparrows from using an

area by removing nests and destroying the eggs and/or

young. House sparrows are very persistent, so this

operation must be repeated at 2-week intervals

throughout the breeding season. Use a long insulated

pole with a hook attached to one end to remove nests

that are located in high places. Nest destruction is

also recommended in shopping malls and around building

signs in urban areas. The nesting materials should be

collected and removed to make it harder for the birds to

find materials for new nests.

Predators. Cats and

sparrows are both abundant in the same human-altered

habitat. A study in one English village found house cats

reduced a resident house sparrow population by 80%

during a year. One farmer has devised a system using

predation to control house sparrows by building catwalks

around the inside of his barn at rafter level. Scrap

lumber was used to provide his farm cats access to

locations where sparrows usually roosted or nested. Once

the cats were able to patrol the barn, the sparrows

quickly vacated the building.

Economics of Damage and Control

Barrows (1889) published

the results of a US Department of Agriculture survey

concerning the status of house sparrows in 1886, about

35 years after their successful introduction. By this

time, house sparrows were recognized as a detriment to

agriculture and native birds. Kalmbach (1940) analyzed

8,004 sparrow stomachs and found that only 20% of the

foods (primarily insects) taken by adult sparrows were

beneficial to humans, 25% were of neutral importance,

and 55% were definitely detrimental to human interests.

While 59% of nestling foods were beneficial to humans

and only 28% injurious, he pointed out that their impact

lasted for only 10 to 12 days.

A recent survey of bird

problems across the United States indicated that 25% of

the respondents in cities had problems with house

sparrows, behind pigeons (71%), blackbirds (54%), and

starlings (42%) (Fitzwater 1988). Extensive measures

with traps are not cost-effective.

Side

Acknowledgments

Figure 1 by Emily Oseas

Routman.

Figures 2 through 4 by the

author, adapted by Jill Sack Johnson.

For Additional Information

Barrows, W. B. 1889. The

English sparrow (Passer domesticus) in North America. US

Dep. Agric., Div. Econ. Ornith. Mammal., Bull. No. 1,

Washington, DC. 405 pp.

Bent, A. C. 1958. Life

histories of North American blackbirds, orioles,

tanagers, and allies. US Natl. Museum Bull. 211,

Washington, DC. pp. 1-27.

Churcher, P. B., and J. H.

Lawton. 1987. Predation by domestic cats in an English

village. J. Zool. (London) 212:439-455.

Dearborn, N. 1927. The

English sparrow as a pest. US Dep. Agric. Farmer’s Bull.

493, Washington, DC. 22 pp.

Fitzwater, W. D. 1982.

Outwitting the house sparrow [Passer domesticus (Linneaus)].

Proc. Great Plains Wildl. Damage Control Workshop

5:244-251.

Fitzwater, W. D. 1988.

Solutions to urban bird problems. Proc. Vertebr. Pest

Conf. 13:254-259.

Grussing, Don. 1980. How

to control house sparrows. Roseville Publ. House,

Roseville, Minnesota. 52 pp.

Kalmbach, E. R. 1940.

Economic status of the English sparrow in the United

States. US Dep. Agric. Tech. Bull. 711, Washington, DC.

66 pp.

Kessler, K. K., R. J.

Johnson, and K. M. Eskridge. 1991. Lines to selectively

repel house sparrows from backyard feeders. Proc. Great

Plains Wildl. Damage Control Workshop. 10:79-80.

Neff, J. A. 1937.

Procedure and methods in controlling birds injurious to

crops in California. Part II: Control methods. Mimeo, US

Dep. Agric. and California State Dep. Agric.,

Sacramento. 153 pp.

Royall, W. C., Jr. 1969.

Trapping house sparrows to protect experimental grain

crops. US Dep. Inter. Bureau Sport Fish. Wildl., Wildl.

Leaflet 484, Washington, DC. 10 pp.

Stokes, D. W. 1979. A

guide to the behavior of common birds. Little, Brown and

Co., Boston. 336 pp.

Summers-Smith, D. 1963.

The house sparrow. Collins, London. 269 pp.

Thearle, R. J. P. 1968.

Urban bird problem. Pages 181-197 in R.K. Murton and E.N.

Wright, eds. The problems of birds as pests. Academic

Press. New York.

Weber, W. J. 1979. Health

hazards from pigeons, starlings and English sparrows.

Thomson Publ., Fresno, California. 138 pp.

Wright, E. N., I. R.

Inglis, and C. J. Feare, 1980. Bird problems in

agriculture. The British Crop Protect. Council, Croydon,

United Kingdom. 210 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

04/05/2006

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|