|

|

|

|

|

BIRDS: Pigeons, Rock Doves |

|

|

Identification

Pigeons (Columba livia)

typically have a gray body with a whitish rump, two

black bars on the secondary wing feathers, a broad black

band on the tail, and red feet (Fig. 1). Body color can

vary from gray to white, tan, and black. The average

weight is 13 ounces (369 g) and the average length is 11

inches (28 cm). When pigeons take off, their wing tips

touch, making a characteristic clicking sound. When they

glide, their wings are raised at an angle.

Range

Pigeons are found

throughout the United States (including Hawaii),

southern Canada, and Mexico.

Habitat

Pigeons are highly

dependent on humans to provide them with food and sites

for roosting, loafing, and nesting. They are commonly

found around farm yards, grain elevators, feed mills,

parks, city buildings, bridges, and other structures.

Food Habits

Pigeons are primarily

grain and seed eaters and will subsist on spilled or

improperly stored grain. They also will feed on garbage,

livestock manure, insects, or other food materials

provided for them intentionally or unintentionally by

people. In fact, in some urban areas the feeding of

pigeons is considered a form of recreation. They require

about 1 ounce (30 ml) of water daily. They rely mostly

on free-stand-ing water but they can also use snow to

obtain water.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

The common pigeon was

introduced into the United States as a domesticated

bird, but many escaped and formed feral populations. The

pigeon is now the most common bird pest associated with

people.

Pigeons inhabit lofts,

steeples, attics, caves, and ornate architectural

features of buildings where openings allow for roosting,

loafing, and nest building. Nests consist of sticks,

twigs, and grasses clumped together to form a crude

platform.

Pigeons are monogamous.

Eight to 12 days after mating, the females lay 1 or 2

eggs which hatch after 18 days. The male provides

nesting material and guards the female and the nest. The

young are fed pigeon milk, a liquid-solid substance

secreted in the crop of the adult (both male and female)

that is regurgitated. The young leave the nest at 4 to 6

weeks of age. More eggs are laid before the first clutch

leaves the nest. Breeding may occur at all seasons, but

peak reproduction occurs in the spring and fall. A

population of pigeons usually consists of equal numbers

of males and females.

In captivity, pigeons

commonly live up to 15 years and sometimes longer. In

urban populations, however, pigeons seldom live more

than 3 or 4 years. Natural mortality factors, such as

predation by mammals and other birds, diseases, and

stress due to lack of food and water, reduce pigeon

populations by approximately 30% annually.

Damage

Pigeon droppings deface

and accelerate the deterioration of buildings and

increase the cost of maintenance. Large amounts of

droppings may kill vegetation and produce an

objectionable odor. Pigeon manure deposited on park

benches, statues, cars, and unwary pedestrians is

aesthetically displeasing. Around grain handling

facilities, pigeons consume and contaminate large

quantities of food destined for human or livestock

consumption.

Pigeons may carry and

spread diseases to people and livestock through their

droppings. They are known to carry or transmit pigeon

ornithosis, encephalitis, Newcastle disease,

cryptococcosis, toxoplasmosis, salmonella food

poisoning, and several other diseases. Additionally,

under the right conditions pigeon manure may harbor

airborne spores of the causal agent of histoplasmosis, a

systemic fungus disease that can infect humans.

The ectoparasites of

pigeons include various species of fleas, lice, mites,

ticks, and other biting insects, some of which readily

bite people. Some insects that inhabit the nests of

pigeons are also fabric pests and/or pantry pests. The

northern fowl mite found on pigeons is an important

poultry pest.

Pigeons located around

airports can also be a threat to human safety because of

potential bird-aircraft collisions, and are considered a

medium priority hazard to jet aircraft by the US Air

Force.

Legal Status

Feral pigeons are not

protected by federal law and most states do not afford

them protection. State and local laws should be

consulted, however, before any control measures are

taken. Some cities are considered bird sanctuaries that

provide protection to all species of birds.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Habitat Modification

Elimination of feeding, watering, roosting, and

nesting sites is important in long-term pigeon control.

Discourage people from feeding pigeons in public areas

and clean up spilled grain around elevators, feed mills,

and railcar clean-out areas. Eliminate pools of standing

water that pigeons use for watering. Modify structures,

buildings, and architectural designs to make them less

attractive to pigeons.

Exclusion

Pigeons can be

excluded from buildings (in some cases very easily) by

blocking access to indoor roosts and nesting areas.

Openings to lofts, steeples, vents, and eaves should be

blocked with wood, metal, glass, masonry, 1/4-inch

(0.6-cm) rustproofed wire mesh, or plastic or nylon

netting.

Roosting on ledges can be

discouraged by changing the angle to 45o or more. Sheet

metal, wood, styrofoam blocks, stone, and other

materials can be formed and fastened to ledges to

accomplish the desired angle. Ornamental architecture

can be screened with 1-inch (2.5-cm) mesh polypropylene

u.v.-stabilized netting to prevent roosting, loafing,

and nesting. To make the netting aesthetically pleasing,

it can be spray painted to match the color of the

building, but black is often the best choice. The life

span of this netting can be as long as 10 years.

In a tool or machinery

shed, barn, hangar, or other similar buildings, roosting

can be permanently prevented by screening the underside

of the rafter area with netting. Nylon netting can be

stapled or otherwise affixed to the underside of rafters

to exclude birds from nesting and roosting. Panels can

be cut into the netting and velcro fasteners can allow

access to the rafter area to service equipment or

lights.

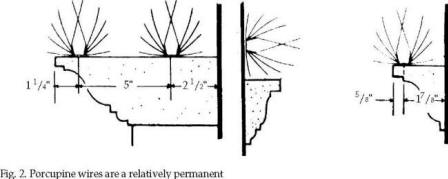

Porcupine wires (Cat

ClawTM, NixaliteTM) are mechanical repellents that can

be used to exclude pigeons. They are composed of a

myriad of spring-tempered nickel stainless steel prongs

with sharp points extending outward at all angles. The

sharp points of these wires inflict temporary discomfort

and deter pigeons from landing on these surfaces. The

prongs are fastened to a solid base that can be

installed on window sills, ledges, eaves, roof peaks,

ornamental architecture, or wherever pigeons are prone

to roost (Fig. 2). Elevate the base with plastic washers

and anchor it with electrical bundle straps. Sometimes

pigeons and sparrows cover the wires with nesting

material or droppings, which requires occasional

removal.

A variation of porcupine

wires, ECOPICTM, mounts flat to a surface and has a

triangular pattern of vertically oriented stainless

steel rods.

Bird Barrier is another

permanent nonlethal mechanical repellent used to exclude

pigeons from structures. It is a stainless steel coil

affixed to a base-mounting strip that can be attached to

structural features as one would with porcupine wires.

Tightly stretched parallel

strands of 16to 18-gauge steel wire or 80-pound+

(36-kg+) test monofilament line can be used to keep

birds off support cables, narrow ledges, conduit, and

similar areas. Attach L-brackets at each end of the area

or item to be protected and fasten the wire to the

L-brackets with turnbuckles. Slack is taken out using

the turnbuckles. L-brackets should be welded or attached

with a cable clamp or aircraft hose clamps (threads on

standard radiator clamps become stripped under the high

torque loads required for holding L-brackets supporting

wire over long distances). On heavily used structures,

it may be necessary to stretch 3 lines at 2, 5, and 7

inches (5, 12, and 18 cm) above the surface.

Overhead monofilament grid

systems, 1 x 1 foot to 2 x 2 feet (30 x 30 cm to 60 x 60

cm), have been used successfully to reducing pigeon

activity in enclosed courtyards. Persistent pigeons will

likely penetrate parallel or grid-wire (line) systems.

Electric shock bird

control systems (Avi-AwayTM, FlyawayTM, and Vertebrate

Repellent System [VRSTM]) are available for repelling

many species of birds, including pigeons. The systems

consist of a cable durably embedded in plastic with two

electrical conductors. Mounting and grounding hardware

and a control unit are included. The conductors carry a

pulsating electric charge. When pigeons make contact

with the conductors and the cable, they receive a shock

that repels but does not kill them. The cable can be

installed in situations also suitable for porcupine

wires and stretched steel wires or monofilament lines.

Although these devices and their installation are

usually labor intensive and/or expensive, their

effectiveness in some cases justifies the investment.

These devices have a life span of 8 years on residential

structures.

Frightening

Noise-making

devices are usually disturbing to humans but have little

permanent effect on roosting pigeons. High-frequency

(ultrasonic) sound, inaudible to humans, is not

effective on pigeons. Revolving lights, waving colored

flags, balloons, rubber snakes, owl models, and other

devices likewise have little or no effect. Roman

candles, firecrackers, and other pyrotechnics may have a

temporary effect but have many limitations in use and

often fail to provide long-term control, especially

against pigeons.

Nesting sites can be

sprayed with streams of water to disperse pigeons, but

this must be done persistently until the birds have

established themselves elsewhere.

Avitrol®

(4-aminopyridine).

Avitrol® is

classified as a chemical frightening agent, but it can

be used as a toxicant in areas where higher mortality is

acceptable. Blend ratios of 1:9 will produce higher

mortality than more dilute applications. See the section

on Toxicants in this chapter for information on

prebaiting and baiting.

Avitrol® for pigeon

control is a whole-corn bait formulated with

4-aminopyridine, a Restricted Use Pesticide and may be

used only by a certified applicator or persons under

their direct supervision. Birds that consume sufficient

amounts of the treated bait usually die. The dying birds

exhibit distress behavior that frightens other members

of the flock away. In order to minimize the mortality

and maximize the flock-alarming reactions, the treated

bait must be diluted with clean, untreated whole corn.

In urban areas where high

bird mortality may cause adverse public reactions, a

blend ratio of 1:19 or 1:29 will produce low mortality,

but requires more time to achieve control. Where high

mortality is acceptable, a blend ratio of 1:9 will

produce quicker population reduction. Prebaiting for at

least 10 to 14 days is critical for a successful

program. At the conclusion of the program, all

unconsumed bait should be recovered to prevent nontarget

birds from ingesting the bait.

Secondary poisoning is

unlikely to occur with Avitrol®, although it is toxic to

any bird through direct ingestion. Avitrol® is designed

to be as selective as possible but should always be used

to minimize the possibility that nontarget species will

have access to the bait. After initial success, Avitrol®

need only be applied periodically following prebaiting

to maintain effective control.

Repellents

Various

nontoxic chemical repellents (polybutenes) such as 4 The

BirdsTM, HotfootTM, TanglefootTM, Roost No MoreTM, and

Bird-ProofTM, are available in the form of liquids,

aerosols, nondrying films, and pastes. These substances

are not toxic to pigeons. Rather, they produce a sticky

surface that the pigeons dislike, forcing them to find

loafing or roosting sites elsewhere.

Building surfaces should

first be cleaned and protected with a waterproof tape

before applying the repellent. Otherwise, sticky

repellents may be difficult to remove or may stain the

building.

Applications should be

made about 1/2 inch (1.3 cm) thick in rows spaced no

farther than 3 to 4 inches (7.6 to 10.2 cm) apart.

Pigeons should not be able to land between the rows

without contacting the repellent. To be effective, all

roosting and/or loafing surfaces in a problem area must

be treated, or the pigeons will move to untreated

surfaces.

The effectiveness of

sticky repellents is usually lost over time, especially

in dusty areas. An application may remain effective for

6 months to 2 years. Some manufacturers have added a

protective second-stage application that forms a crust

on the repellent and helps extend the life of the

repellent in dusty or hot areas. Some pest control

operators spray clear shellac over the applied repellent

to accomplish the same affect.

Although chemical

repellents offer effective results in many situations,

there are several important considerations. First,

repellents are not aesthetically pleasing. Second, they

can be annoying to professional window cleaners in urban

areas. Third, nesting pigeons will occasionally drop

sticks and straw over the repellents and continue to

nest. Fourth, high temperatures may cause the material

to run down the sides of buildings, while cold

temperatures may cause the repellent to become too stiff

for the bird’s feet to penetrate. Finally, chemical

repellents are most appropriate for small- and

medium-sized jobs. For large commercial situations

requiring significant amounts of labor and expensive

equipment, the use of repellents may be economically

shortsighted because they are expensive to reapply

frequently.

Naphthalene is a repellent

that may offend the bird’s olfactory sense. Naphthalene

flakes are federally registered as a repellent for

pigeons, though they are not registered in every state.

Upon evaporation, naphthalene produces a strong odor

that repels pigeons from enclosed areas such as attics

and wall voids. The flakes are spread on the attic floor

or between walls, using about 5 pounds (2.3 kg) for

every 2,000 cubic feet (56 cu. m) of space. After the

birds have departed, all openings must be closed to

prevent reentry. The strong odor produced by naphthalene

flakes is also disagreeable and irritating to some

people. Prolonged breathing of the vapor should be

avoided.

Toxicants

Pigeon control

using toxicants may require special permits issued

through various state agencies such as state departments

of agriculture, health, or wildlife.

Toxic Baits

Prebaiting.

Prebaiting is the single most important element of a

successful toxicant program. The birds must be trained

to feed on a specific bait at specific sites before the

toxicant is introduced. If the prebaiting is not done

correctly, the results will likely be less than

desirable.

Before any control work is

attempted, the daily movement patterns of the birds

between feeding, loafing, and roosting areas must be

determined. Several potential baiting sites can then be

selected. The number of bait sites selected depends on

the size of the area being treated and the number of

birds involved, but if possible, three to five baiting

sites should be used. Establish bait sites in locations

normally frequented by the birds, free from

disturbances, and where rigid control over access can be

maintained at all times. Generally, the closer the bait

site is to the normal feeding site, the more successful

the program.

In urban areas, flat

rooftops make excellent bait sites, even though pigeons

do not normally feed on them. They do normally frequent

rooftops, however, and it is possible to control access

to them. With persistence, pigeons can be trained to

feed almost anywhere.

Every effort must be made

to reduce or eliminate food sources other than the

prebait so that pigeons will have to rely solely on the

prebait. It must be as nearly identical to the toxic

bait as possible. Generally, the best prebait and bait

is clean, untreated whole corn. Whole corn is

recommended because smaller resident birds, such as

sparrows, are physically incapable of swallowing it,

thus reducing the possibility of poisoning these birds.

Also, corn is a high-energy food and is therefore

preferred by pigeons, especially during the winter

months. A constant supply of fresh, acceptable prebait

must be made available to the birds at all times. There

should always be a little prebait left over when the

birds finish feeding. It is impossible to train birds to

feed at a site where they cannot get enough to eat.

Therefore, all birds must have the opportunity to feed

or they will simply go elsewhere. Once the pigeons have

been trained to feed at the selected locations, the

toxic bait may be applied.

Prebaiting and subsequent

toxic baiting should be done at the same time of day and

in the same manner. Pigeons usually feed most vigorously

shortly after leaving the roost early in the morning.

Therefore, prebait and bait should be placed before

dawn. The duration of the prebaiting period will vary as

each case is different. Usually, 2 weeks of prebaiting

is most effective.

Apply the prebait on firm,

relatively smooth surfaces, or on wide, shallow wooden

or metal trays. This helps the applicator maintain

control of the prebait and poison bait, and will

facilitate the removal of any unused material at the end

of the control program. Record the quantity of prebait

placed and consumed each day so that the correct amount

of treated bait to be used can be determined. Generally,

100 feeding pigeons will eat about 7 to 8 pounds (15 to

18 kg) of whole corn per day.

The prebait and toxic bait

should be placed in numerous small piles so that all

birds can feed at one time. Never place the prebait or

toxic bait in one pile. For large flocks (100 birds or

greater), 8 to 12 piles containing 1 pound (454 g) of

grain each may be necessary. Small flocks of less than

100 birds can be accommodated with three to four piles.

During the prebaiting

period, the site must be carefully observed to ensure

that the prebait is not attracting nontarget birds such

as cardinals, blue jays, or doves. If protected birds

appear at a bait site, continue to put out the prebait

to keep the protected birds there while toxic baits are

put out elsewhere. Do not place toxic baits at sites

used by nontarget birds. If protected birds begin using

all the locations, new bait sites will have to be

established or the plan to use toxic baits abandoned.

Poisoning birds is a

complex task that requires careful attention to details.

Do not take shortcuts, especially in prebaiting.

Baiting and Baits

All prebait

must be removed before the toxic bait is applied. When

the toxic bait is put out, the feeding birds should not

be disturbed but should be observed from a hidden

location.

DRC-1339

(3-chloro-p-toluidine hydrochloride). DRC-1339 is a

Restricted Use Pesticide registered for the control of

pigeons. It can only be used by USDA-APHIS-ADC employees

or persons working under their direct supervision.

The toxicity of DRC-1339

to birds varies considerably. Starlings, red-winged

blackbirds, crows, and pigeons are most susceptible, but

house sparrows and hawks are somewhat resistant.

Therefore, DRC-1339 may be a toxicant that provides a

higher margin of safety than the other toxicants for use

in cities where peregrine falcons have been introduced.

Generally, mammals are not sensitive to the toxic

effects of DRC-1339.

DRC-1339 is slow-acting

and apparently painless. It takes from several hours to

3 days for death to occur. Death is caused by uremic

poisoning and occurs without convulsions or spasms as in

the case of other toxicants. DRC-1339 is metabolized

within 2 1/2 hours after ingestion. Normally, there is

little chance of undigested bait remaining in the crop

or gut of dead or dying pigeon. The excreta and the

flesh of pigeons poisoned with DRC1339 are nontoxic to

predators or scavengers.

Because of the slow rate

of death, the majority of dead birds are usually found

at the roost site. Since bait shyness does not develop,

DRC-1339 allows for baiting programs to be extended

until control is achieved. Areas where pigeons roost or

loaf should be monitored so that carcasses can be picked

up.

As in other baiting

programs, prebaiting is critical to successful control.

Prebaits and carriers for toxic baits can be made from

one of the following: oat groats, cracked corn, whole

corn, commercial wild bird seed, or commercial poultry

mix. A good technique is to use more than one type of

prebait, in order to assess which is better accepted by

the target population.

Do not bait sites where

prebait has not been accepted well or where nontarget

species have been consuming prebait.

Contact Poisons

The Rid-A-BirdTM

perch contains 11% fenthion, a Restricted Use Pesticide,

and is registered for pigeon control. These perches are

hollow tubes that hold about 1 ounce (28 ml) of the

toxicant within a wick. When a bird lands on the perch,

the toxicant is absorbed through the feet in a short

period of time. Death usually takes place within 24 to

72 hours. Pigeons may die at the roost site or some

distance away if contact was made at a feeding or

loafing area.

Perches are available in a

number of configurations for both indoor and limited

outdoor applications. The wide perch, 1 x 24 inches (2.5

x 61 cm), is used to accommodate the sitting (nongrasping)

habit of pigeons (Fig. 3). Ten to 12 perches will solve

most problems, but large jobs may require as many as 30

perches. For example, in a warehouse measuring 50 x 100

feet (15 x 30 m), most pigeons can be eliminated by

placing one or two perches in each heavily used area.

Effective places to install perches around struc-tures

can be determined if the area is observed for preferred

perching areas for 48 hours before placement.

Toxic perches should be

used only by persons experienced with their usebecause

they can be hazardous to other birds, animals, and

people if used incorrectly. Label instructions must be

rigidly followed.

Fenthion may present a

secondary hazard to birds of prey, small carnivores, and

scavengers. Any nontarget animals, including humans,

that come in contact with the perch itself could absorb

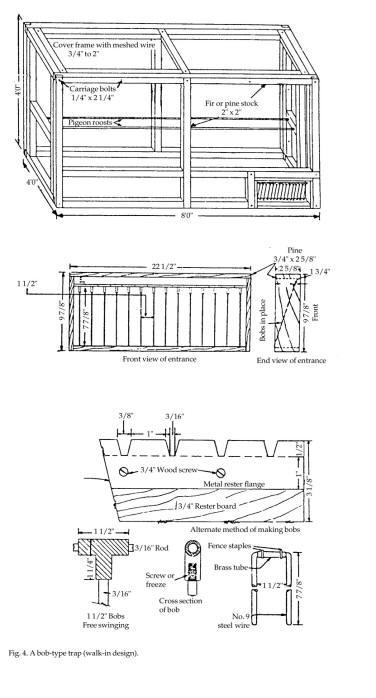

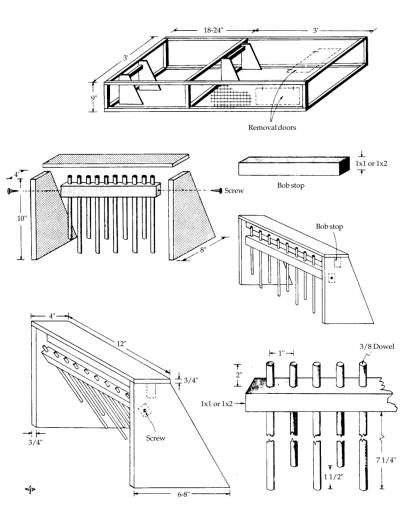

a fatal amount of fenthion. Trapping Pigeons can be

effectively controlled by capturing them in traps placed

near their roosting, loafing, or feeding sites. Some

traps, such as the common pigeon trap (Fig. 4), are over

6 feet (2 m) tall, while low-profile traps (Fig. 5)

measure only 9 inches (23 cm) high and 24 inches (61 cm)

in width and length. Generally, the larger the

population of birds to be trapped, the larger the trap

should be. Although larger traps hold many birds, they

can be cumbersome in situations such as rooftop trapping

programs. In these instances, it may be more convenient

to use several low-profile traps that are more portable

and easier to deploy. Small portable traps, such as the

funnel trap or the lily-pad trap (Fig. 6), can be easily

constructed and deployed. Live traps and/or trap parts

designed for the capture of small birds are also

commercially available (see Supplies and Materials).

Fig. 3 Rid-A-BirdTM perch for pigeons.

Trapping

Tips for

Effective Trapping. The best locations for traps are

major pigeon loafing areas. During the heat of the

summer, place traps near pigeonwatering sites such as

rooftop cooling condensers. Also consider prebaiting

areas for several days before beginning the actual

trapping. To prebait, place attractive baits, such as corn or milo, around the outside of the traps.

After 3 to 4 days, the baits can be placed inside the

trap (in both compartments of the low-profile trap).

Four or five decoy birds should be left in the trap to

lure in more pigeons.

such as corn or milo, around the outside of the traps.

After 3 to 4 days, the baits can be placed inside the

trap (in both compartments of the low-profile trap).

Four or five decoy birds should be left in the trap to

lure in more pigeons.

Visit traps at least every

other day. Fresh food and water must be provided at all

times for decoy birds. If “trap-shyness” develops, traps

can be left open for 2 to 3 days and then reset again

for 4 to 5 days. Select another site if traps fail to

catch a sufficient number of birds. The disposal of

trapped birds should be quick and humane. The act of

inducing painless death is called euthanasia. There are

several options to select from, including inhalant

agents, noninhalant pharmacologic agents, and physical

methods. Review the 1986 report of the American

Veterinary Medical Association panel on euthanasia when

selecting a humane disposal method.

For large-scale pigeon

control projects, the most cost-effective and humane

method is to use a carbon monoxide (CO) or carbon

dioxide (CO2) gas chamber. These chambers utilize

commercially available compressed CO or CO2 in gas

cylinders. The chambers can be purchased commercially or

be constructed by modifying a garbage can or 55 gallon

(209 l) drum with a tight-fitting lid having a hole for

a gas supply line. Birds will expire in 5 to 7 minutes

(using CO or CO2), when the gas flow displaces

approximately 20% of the chamber volume per minute.

Chambers should be used in well-ventilated areas,

preferably outside, to protect personnel.

Fig. 5. A bob-type trap (low-profile design).

Fig. 6. (a) Lily-pad trap

and clover-leaf trap; (b) double funnel trap.

Double Funnel Trap

Releasing pigeons back to

the “wild” is impractical. Pigeons are likely to return

even when released 50 or more miles (>80 km) from the

problem site, or become pests in other communities.

Cannon Nets.

A cannon net may be effective and practical where

pigeons congregate in large numbers on the ground (for

instance, rail yards and grain-handling facilities).

Cannon nets are large sections of netting attached to

explosive charges that are activated when birds are

within range. They can be set up adjacent to areas where

pigeons visit on a daily basis to feed. The net operator

observes from a hidden location and activates the

explosive propellent with an electrical charge. The

netting travels over the birds, then drops on the flock.

Cannon nets can capture up to 500 birds at a time.

Shooting

Where

permissible, persistent shooting with .22 caliber rifles

(preferably using ammunition loaded with short-range

pellets), .410 gauge shotguns, or high-powered air

rifles can eliminate a small flock of pigeons. For

example, shooting can be an effective technique to

remove the few pigeons that may persist around farm or

grain elevators after a reduction program has been

terminated.

Most towns and cities have

ordinances prohibiting the discharge of firearms within

corporate limits. Check local laws before employing a

shooting program.

Other Control Methods

Alpha-chloralose. Alpha-chloralose is an immobilizing

agent that depresses the cortical centers of the brain.

Pigeons fed about 60 mg/kg of alpha-chloralose become

comatose in 45 to 90 minutes. The pigeons can then be

captured to be relocated or euthanized. Full recovery

occurs 4 to 24 hours later.

The Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) has granted USDA-APHIS-ADC

authority to use alpha-chloralose to capture pigeons

under a perpetual Investigational New Animal Drug

Application (INADA). The INADA is the only legal way to

use alpha-chloralose as a wildlife immobilizing agent.

The drug can be legally obtained for this use only from

the Pocatello Supply Depot. Only USDA-APHIS-ADC

personnel certified in its use or individuals under

their supervision are allowed to use alpha-chloralose.

Nest Destruction

Destroying nests and eggs at 2-week intervals can be

helpful in reducing pigeon numbers. This technique,

however, should be used in conjunction with other

control methods.

Economics of Damage and Control

Structures inhabited by

pigeons can sustain damage from droppings and harbor

disease. The droppings can also make structural surfaces

slick and hazardous to walk or climb on.

Washing acidic

accumulations of droppings to prevent structural damage

can cost in excess of $10,000 per year. The longevity of

industrial roofing materials can be adversely affected

by droppings, resulting in expensive replacement costs.

Employee health claims and

lawsuits resulting from diseases or injuries attributed

to pigeons can easily exceed $100,000.

An integrated pigeon

management program incorporating lethal and nonlethal

control techniques is well worth the investment when

considering the economic damage and health threats

caused by large populations of pigeons.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to Mr.

Fred Courtsal, retired USDA-APHIS-ADC state director,

for his work in compiling the original chapter on pigeon

control. Many ADC field personnel provided valuable

input regarding updates and revisions on pigeon control.

We would also like to thank Kathleen LeMaster and Dee

Anne Gillespie, who coordinated revisionary corrections.

Figure 1 by Emily Oseas

Routman.

Figure 2 courtesy of

Nixalite Company of America.

Figure 3 by Renee Lanik,

University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Figures 4, 5, and 6 from

US Fish and Wildlife Service (1961), Trapping Pigeons,

Leaflet AC 206, Purdue University, West Lafayette,

Indiana.

For Additional Information

American Veterinary

Medical Association. 1986. Report of the American

Veterinary Medical Association panel on euthanasia. J.

Amer. Veterin. Med. Assoc. 188(3):252-268.

Bennett, G. W., J. M.

Owens, and R. M. Corrigan. 1989. Pigeon control. Pages

333-336 in Truman’s scientific guide to pest control

operations. Purdue Univ./Edgell Commun. Duluth,

Minnesota. 539 pp.

Corrigan, R. M. 1989. A

guide to managing pigeons and sparrows. Pest Control

Tech.17(1):38-40, 44-46, 48-50.

Corrigan, R. M., D. E.

Williams, and F. Courtsal. 1989. Pigeons, ADC-1. Coop.

Ext. Serv. Purdue Univ. West Lafayette, Indiana. 6 pp.

Department of the

Interior, US Fish and Wildlife Service. 1961. Trapping

pigeons, ADC-206. Coop. Ext. Serv. Purdue Univ., West

Lafayette, Indiana. 2 pp.

Jackson, W. B. 1978.

Rid-A-BirdTM perches to control bird damage. Proc.

Vertebr. Pest Conf. 8:47-50.

Marsh, R. E., and W. E.

Howard. 1990. Vertebrate pests. Pages 771-832 in A.

Mallis, ed., Handbook of pest control. 7th ed. Franzak

and Foster Co., Cleveland, Ohio.

Martin, C., and L. R.

Martin. 1982. Pigeon control: an integrated approach.

Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 10:190-192.

Murton, R. K., R. J. P.

Thearle, and J. Thompson. 1972. Ecological studies of

the feral pigeon, Columba livia var. J. Appl. Ecol.

9:835-874.

Scott, H. G. 1961.

Pigeons, public health importance and control. Commun.

Disease Center. Atlanta, Georgia. 17 pp.

Weber, W. J. 1979. Health

hazards from pigeons, starlings and English sparrows.

Thomson Pub., Fresno, California, 138 pp.

Woronecki, P. P. 1988.

Effect of ultrasonic, visual and sonic devices on pigeon

numbers in a vacant building. Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf.

13:266-272.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

01/09/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|