|

|

|

|

|

BIRDS: Magpies |

|

|

Identification

Magpies have lived in

close association with humans for centuries. They are

found throughout the Northern Hemisphere and are a

common bird of tales and superstitions. Magpies and

their many brash behaviors are the basis for the cartoon

characters Heckyl and Jeckyl.

Magpies are members of the

corvid family, which also includes ravens, crows, and

jays. They are easily distinguished from other birds by

their size and striking black and white color pattern.

They have unusually long tails (at least half of their

body length) and short, rounded wings. The feathers of

the tail and wings are iridescent, reflecting a

bronzy-green to purple. They have white bellies and

shoulder patches and their wings flash white in flight.

Like other corvids, they are very vocal, even

boisterous. Typical calls include a whining “maag” and a

series of loud, harsh “chuck” notes. Where magpies are

not harassed, they can be extremely bold. If hunted or

harassed, though, they become elusive and secretive.

Two distinct species are

found in North America, the black-billed and

yellow-billed magpies (Fig. 1). They are easily

separated by bill color, as their names imply, and by

geographic location. Black-billed magpies average 19

inches (47 cm) in length and 1/2 pound (225 g) in

weight. They have black beaks and no eye patches.

Yellow-billed magpies are somewhat smaller (17 inches

[42 cm]) and weigh slightly less than 1/2 pound (225 g).

Their bills and bare skin patches behind their eyes are

bright yellow.

Range

Magpies are found in

western North America. Ranges of the two species do not

overlap. Black-billed magpies are found from coastal and

central Alaska to Saskatchewan, south to Texas, and west

to central California, east of the Sierra-Cascade range.

They migrate in winter to lower elevations, and in

northern parts of their range, south to areas within

their breeding range. Occasionally they wander to areas

further east and south of their normal range.

Yellow-billed magpies are

residents of the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys of

central California and range south to Santa Barbara

County. They do not wander outside of their normal range

as often as black-billed magpies, but they have been

found in extreme northern California.

Habitat

Magpies are associated

with the dry, cool climatic regions of North America.

They are typically found close to water in relatively

open areas with scattered trees and thickets. The

black-billed magpie inhabits foothills, ranch and farm

shelterbelts, sagebrush, streamside thickets, parks, and

in Alaska, coastal areas. The yellow-billed magpie

inhabits farmlands, stream groves, and areas with

scattered oaks or tall trees. Their range coincides with

a few species of mistletoe that are often used in

building their nests.

Food Habits

Magpies are omnivorous and

very opportunistic, a characteristic typical of other

corvids. They have a preference for animal matter,

primarily insects, but readily take anything that is

available. Congregations of magpies can commonly be seen

along roadsides feeding on animals killed by cars or in

ripening fruit and nut orchards. They also pick insects

from the backs of large animals and were historically

associated with large herds of bison. Their diet changes

during the year, reflecting the availability of foods

during the different seasons.

The black-billed magpie’s

diet typically consists of over 80% animal matter:

insects, carrion, small mammals, small wild birds,

hatchlings, and eggs. The remainder of its diet consists

of fruits and grains. The yellow-billed magpie’s diet is

about 70% animal matter and 30% fruits, nuts, and

grains. Nestling magpies are fed a diet of mostly animal

matter, primarily insects.

Magpies often store or

cache food items in shallow pits that they dig in the

ground. This behavior is commonly observed in winter,

but can be seen throughout the year.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Magpies, like other

corvids, are intelligent birds. They learn quickly and

seem to sense danger. They are boisterous and curious,

but shy and secretive in the presence of danger. They

mimic calls of other birds and can learn to imitate some

human words. They have readily adapted to the presence

of humans and have taken advantage of new food sources

provided.

Magpies are gregarious and

form loose flocks throughout the year. Pairs stay

together yearlong, but mates are replaced rapidly if one

is lost. Nest building typically begins in early March

for black-billed magpies and earlier for yellow-billed

magpies. Black-billed magpies build large nests,

sometimes 48 inches (125 cm) high by 40 inches (100 cm)

wide, made of sticks in low bushes or in trees usually

within 25 feet (7.5 m) from the ground. The nest chamber

is a cup lined with grass and mud, and normally enclosed

by a canopy of sticks. Two entrances are common.

Yellow-billed magpies build similar nests, but theirs

often resemble mistletoe clumps, which are common in

trees where they nest. Magpie nests are usually found in

small colonies. Magpies nest once a year, but will

renest if their first attempt fails. Other species of

birds and mammals often use magpie nests after they have

been abandoned.

Black-billed magpies lay 6

to 9 eggs, whereas yellow-billed magpies lay 5 to

8. Incubation normally

starts in April, except further north where it may begin

as late as mid-June. The incubation period is 16 to 18

days and young are able to fly 3 to 4 weeks after

hatching. Young forage with the adults and then join

other groups in summer to form loose flocks. Winter

congregations may include more than 50 individuals.

Yellow-billed magpies, though, may form nightly roosts

of 50 or more soon after nesting.

Magpies are not swift

fliers. They elude predators and danger by flitting in

and out of trees or diving into heavy cover. They

usually stay near cover, but often forage in open areas

on the ground. Like other corvids, magpies walk with a

strut and hop quickly when rushed. They are found close

to water, using it for drinking and bathing.

Damage and Damage Identification

Magpies have come into

conflict with humans in North America for quite some

time. Poisons were used extensively in the 1920s and 30s

to resolve serious depredations and livestock predation.

During this time, magpie populations were greatly

suppressed. Today, however, no toxicants are currently

registered and populations have increased. Magpies cause

a variety of problems, especially where their numbers

are high. Most problems occur in localized areas where

loose colonies have concentrated in close proximity to

humans.

Magpies can cause

substantial damage locally to crops such as almonds,

cherries, corn, walnuts, melons, grapes, peaches, wheat,

figs, and milo. Their damage is probably greatest in

areas where insects and wild mast are relatively

unavailable. Typically, other birds such as blackbirds

and robins cause more damage to growers in fruit

orchards and grain fields because of their greater

abundance.

Magpies are often found

near livestock where they feed on dung-and

carrion-associated insects. They also forage for ticks

and other insects on the backs of domestic animals.

Perhaps the most notorious magpie behavior is the

picking of open wounds and scabs on the backs of

livestock. If they find an open wound, such as that from

a new brand, they may pick at it until they create a

much larger wound. The wound may eventually become

infected and, in some instances, may kill the animal.

Magpies, like ravens, may peck the eyes out of newborn

or sick livestock.

Magpies rob wild bird and

poultry nests of eggs and hatchlings. Typically, that

does not affect wild bird populations except in local

areas where limited habitat makes nests easy to find.

They can be very destructive to poultry, however,

especially during the nesting season when magpie parents

are gathering food for their young.

Magpie roosts can be a

nuisance because of excessive noise and the odor

associated with droppings. During winter, magpies may

congregate in loose colonies and form nightly roosts of

hundreds after they have migrated southward and to lower

elevations. They typically roost in dense thickets or

trees.

Legal Status

Magpies are protected as

migratory nongame birds under the Federal Migratory Bird

Treaty Act. Under the Federal Codes of Regulation (CFR

50, 21.43) it is stated, however, that “a Federal permit

shall not be required to control . . . magpies, when

found committing or about to commit depredations upon

ornamental or shade trees, agricultural crops,

livestock, or wildlife, or when concentrated in such

numbers as to constitute a health hazard or other

nuisance. . . .” Most state or local regulations are

similar, but consult authorities before taking any

magpies.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Exclusion is

generally not feasible to protect crops from magpie

depredation unless crops are of high value or the area

to protect is relatively small. Nylon or plastic mesh

netting can be used to cover crops, but netting is

expensive and labor-intensive, making it uneconomical to

use in most situations. Netting can be used to protect

individual trees and is most appropriate in small areas

where depredation is extreme.

Exclusion is an ideal

method to keep magpies from livestock when it is

economical to do so. Poultry nests and young kept in

fenced coops and feeding areas (maximum 1 1/2-inch

[3.8-cm] mesh) are relatively safe from magpies. Lambing

pens can reduce the incidence of eye pecking. Livestock

with open wounds or diseases can be kept in areas that

exclude magpies until they are healthy.

Habitat Modification

Predation on

poultry often increases during magpie breeding season.

Raids of increasing intensity can often be tied to a few

offending breeding pairs with young. Removal of their

nests can effectively reduce predation. If removal takes

place early in the nesting season, magpies may renest,

often in a completely new area.

Clear low brush to reduce

nesting habitat in areas where several black-billed

magpies are regularly concentrated and cause significant

yearly damage. This method reduces habitat for all

wildlife, however, and should be carefully considered

before undertaken.

Removing or thinning roost

trees will force magpies to find new roost sites. The

primary factor to consider is the number of trees that

need to be removed to satisfactorily reduce cover so

magpies will relocate. Usually, the removal of only a

few trees will discourage magpies.

Frightening

Frightening

devices are effective for reducing magpie depredations

to crops and livestock. Several methods are used to

frighten birds and are explained in greater detail in

the chapter on Bird Dispersal Techniques in this manual.

A combination of human presence, scarecrows,

pyrotechnics (fireworks), and propane cannons provide a

good frightening or hazing program and can reduce

depredations significantly. The cost of using each of

these techniques must be compared to determine the most

effective combination to obtain the greatest

benefit-cost ratio. The success of these devices varies

greatly with location, availability of alternate food

supplies (such as insects and wild mast), and how the

techniques are used.

In a hazing program, the

periodic presence of a person is important because it

reinforces most techniques. The mere presence of a

person will normally keep magpies at a distance,

especially where magpies have been hunted.

Frightening devices such

as scarecrows and other effigies, eye-balloons, hawk

kites, and mylar (reflective) tape are used to deter

magpies. Most are effective for only a short time, but

their effectiveness can be extended by moving them

regularly. The human scarecrow is still one of the most

effective frightening devices. Painted eyes on both

front and back of the head and arms made of flaps that

blow in the wind will increase its effectiveness. Place

scarecrows at regular intervals in the threatened area

(one for every 2 to 10 acres [1 to 4 ha]) along with a

combination of other frightening devices.

Pyrotechnics or fireworks

can be used to repel animals. These explode, whistle, or

scream after being ignited. Typical pyrotechnics are

shellcrackers, rope firecrackers, and racket and whistle

bombs. These can be purchased from suppliers, but some

states require a permit from the state fire marshal.

Shellcrackers are probably the most widely used and are

shot from a 12-gauge shotgun, travel about 75 yards (70

m), and then explode. The 15 mm pistol launcher,

however, is more economical, easier to carry, and allows

reports and whistle and racket bombs to be shot. The

variety seems to be more effective for magpies. The

projectiles travel from 35 to 70 yards (30 to 65 m)

depending on the style. These can be shot whenever

magpies are seen in the damage area, but conservative

use will reduce acclimation. Check state and local laws

regarding pyrotechnics.

Propane cannons fire loud

blasts at timed or random intervals. A variety of styles

are available. Conceal cannons in threatened areas, move

them every 3 to 5 days, and use sparingly to avoid

habituation. For magpies, the blast interval should be

no greater than one every 2 minutes and the interval

should be varied. Shooting a few magpies with a shotgun

and using pyrotechnics will increase the effectiveness

of propane cannons.

Repellents

No effective

chemical repellents are available for magpies.

Toxicants

None are

registered.

Trapping

Trapping is

effective in reducing local magpie populations and

damage where they have concentrated in high numbers

because of food availability or winter conditions.

Several trap designs have been successful in capturing

magpies. Traps made of weathered materials are most

successful, but still require time for magpies to become

accustomed to them. Traps are most effective in areas

frequented by magpies or along their flight paths into

damage areas. Consult federal, state, and local laws

before trapping.

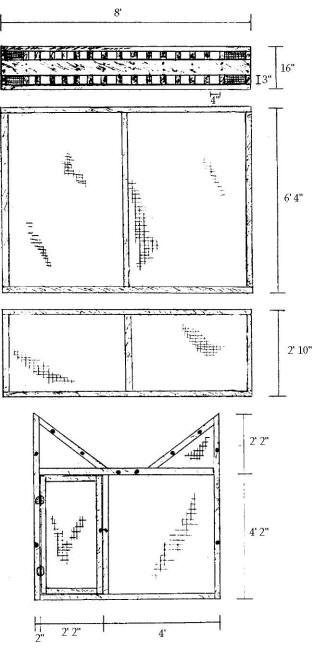

An effective trap design

commonly used for capturing magpies is the modified

Australian crow trap (Fig. 2). This is an inexpensive

decoy trap that becomes more effective after the first

birds (decoys) are caught. The standard measurements in

figure 2 can be modified to facilitate transportation

and storage, but the dimensions of the ladder openings

or slots must remain the same. The trap can also be

built to fit onto a trailer for transporting from one

site to another.

The modified Australian

crow trap has been used effectively in Washington and

Oregon by baiting the trap with a red-colored, dry dog

food. Initially, place dog food on the middle slat of

the ladder until the first magpies are caught. Inside

under the slots, place 10 pounds of dog food and water.

Carrion, such as a chicken carcass or a road-killed

rabbit, can also be used as an attractant. Check the

trap daily, remove all but two magpies, and replace bait

and water as needed. Nontarget birds that are captured

should be immediately released unharmed. This trap can

take several magpies, but it does require some time and

expense to maintain properly.

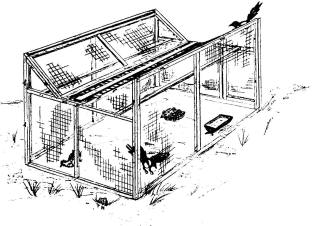

Another trap design that

has been successful for trapping magpies in Alberta is a

circular-funnel trap (Fig. 3). Prebait the area to be

trapped. After magpies start feeding, place the trap

nearby where they can adjust to it. To attract magpies

into the trap, place a line of bait leading into it.

After the first birds are caught, remove all but one or

two decoys and any remaining prebait. Keep trapping an

area until most magpies are caught and then move the

trap to a new location. This trap is probably not as

efficient as the crow trap for catching large numbers of

birds, but it is not as cumbersome and may be more

effective at trapping magpies prone to feeding on the

ground.

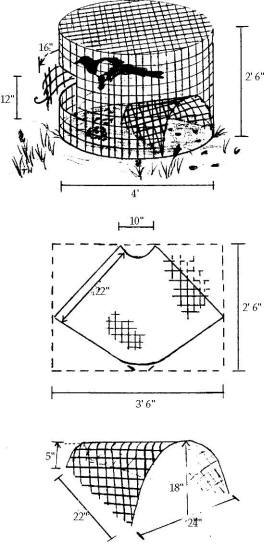

Padded-jaw pole traps can

also be used to take a few offending magpies. These are

leghold traps, No. 0 or 1 coil or jump spring, placed on

5- to 10-foot poles that are erected in threatened areas

(Fig. 4). They can also be placed on routinely used

perches. Traps do not have to be covered. The jaws need

to be well padded with foam rubber or cloth and wrapped

with electrician’s tape to allow the leg to be snugly

caught without breaking it. Run a heavy-gauge wire

through the trap chain ring and staple the wire to the

top and bottom of the post, allowing magpies to slide to

the ground and rest. Both sides of the trap should be

anchored with fine wire or thread to give the trap some

stability. Other perches that cannot have traps placed

on them should be removed or covered with tack board or

porcupine wire to prevent magpies from landing. Traps

must be monitored frequently and placed in areas where

nontarget capture is highly unlikely. Be sure to check

all laws regarding the use of pole traps.

Fig. 2. Modified

Australian crow trap for magpies: a) entrance ladder

(top view); b) side panel; c) top panel; d) end panel

with door; and e) assembled trap. Materials Needed:

28 8 foot, 2 x 2-inch

boards

Cut these into:

12, 8 feet; 10, 6 feet; 4,

4 feet; 4, 34 inches; 6,

30 inches; 2, 22 inches;

17, 12 inches

1 8 foot, 1 x 6-inch board

56 feet of 4-foot-high, 1 x 2-inch wire mesh 24 4 1/2

inch bolts with wing nuts and 2 washers

2 small door hinges

1 door hook latch or

locking style

3 1/2 inch nails, staples,

haywire

Assembly Instructions:

Construct the entrance

ladder. Cover both ends with wire-mesh pieces 7 x 16

inches. Make two side, top, and end panels. One end

panel is constructed with a support beam in the center

(as pictured in the assembled trap) and the other with a

door. Cut and tightly staple wire mesh to the inside

walls. Cut or file any sharp projections that will

protrude into the cage. Assemble the trap, holding it

together with baling wire. Drill 10 holes in the end

panels (shown in d) and through the adjacent panels. Put

bolts through these holes with washers on both sides and

secure with wing nuts. The side panels and entrance

ladder can be snugly held to the top panels with haywire

or bolts.

Fig. 3. Circular-funnel

magpie trap: a) assembled trap; b) wire mesh cut for

funnel; c) shaped funnel. Materials Needed:

1

1/4-inch reinforcing rod 12 2/3 feet long 1 1

1/4-inch reinforcing rod 12 2/3 feet long 1

1 2 foot 6 inches x 12

foot 8 inches piece of 1-inch welded-wire mesh

2 2 foot 6 inches x 4 foot

wire mesh (cut to fit top) 1

1 2 foot 6 inches x 3 foot

6 inches wire mesh (cut and tapered for funnel)

3 stakes about 10 inches

long with ‘U-shaped’ heads

Assembly Instructions:

Bend the 1/4-inch rod in a

circle and weld. Attach the 12-foot 8-inch wire mesh

piece to the rod with haywire and crimp the ends of the

wire mesh around the rod. Cut out the funnel, shape, and

attach to the ground-side, inside wall with haywire. Cut

out the wall according to the size of the tunnel

opening. Cut out the rectangular opening (12 x 16

inches) on three sides opposite the funnel, but leave

the fourth side as a hinge for a door to remove magpies.

If light-gauge wire is used, an additional reinforcing

rod around the top and on the sides may be needed to

make the trap sturdy. Cut out the top and attach. Stake

down the trap in the area to be trapped.

Fig. 4. Padded-jaw pole trap.

Shooting

Shooting can be

an effective means to eliminate a few offending magpies

or to reduce a local population. Shotguns are

recommended for shooting. Magpies can be stalked or shot

from blinds under flight paths. They also can be lured

with predator calls. Magpies, though, quickly become

wary and learn to avoid hunters. Shooting in conjunction

with a hazing program provides greater control of damage

than does shooting alone. Consult local, state, and

federal laws on shooting.

Economics of Damage and Control

Magpies benefit agricultural producers by consuming

thousands of insects and by scavenging, but they can

also have a negative local impact that can turn severe.

Losses are greatest where nesting magpies are in close

proximity to poultry producers or concentrated in

numbers that constitute a problem. Damage may increase

dramatically when wild mast and insects are relatively

unavailable.

Each producer in the range

of magpies should develop a management plan before

magpies become a problem. Preparedness enhances the

success in decreasing depredation. The cost of the

different options for control should be weighed and

compared with the success in controlling the problem.

Long-term solutions should be implemented wherever

possible, but be prepared to take remedial control

measures when necessary. Prior to the depredation

season, an estimate of the magpie population and the

availability of alternate food sources should be

determined to make preparations accordingly.

Acknowledgments

I thank Mike Dorrance

(Alberta Agric., Edmonton), Michael Pitzler

(USDA-APHIS-ADC, Washington), Edward Shafer

(USDA-APHIS-ADC, Denver Wildlife Research Center), and

the authors of the articles used to gather the

information. I would also like to thank the reviewers

for their comments, especially Alan Foster

(USDA-APHIS-ADC, Colorado) who provided a detailed

review of this article.

Figure 1 by the author.

Figures 3 and 5 courtesy

of US Dep. Agric.

Figure 4 courtesy of

Alberta Agric.

For Additional Information

Alberta Agriculture. 1983. An improved magpie trap.

Alberta Agric. Print Media Branch. Agdex 685-3. 3 pp.

Bent, A. C. 1964. Life

histories of North American jays, crows and titmice.

Dover Pub., Inc., New York. 495 pp.

Birkhead, T. R. 1991. The

magpie: the ecology and behavior of black-billed and

yellow-billed magpies. Poyser Popular Bird Books,

Academy Press. 300 pp.

Kalmbach, E. R. 1927. The

magpie in relation to agriculture. US Dep. Agric. Tech.

Bull. 24. Washington DC. 29 pp.

Kalmbach, E. R. 1944.

Local control of magpies through destroying nests and

roosts and through trapping. US Fish Wildl. Serv. Wildl.

Leaflet 252. 4 pp.

Linsdale, J. M. 1937. The

natural history of magpies. Pacific Coast Avifauna No.

25. Cooper Ornith. Club Publ., Calif. 234 pp.

McAtee, W. L. 1933.

Protecting poultry from predacious birds. US Dep. Agric.

Leaflet 96. 6 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

E-86

01/09/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|