|

|

|

|

|

BIRDS: Hawks and Owls |

|

|

Fig. 1. Raptors,

representative of those that may cause damage by preying

on poultry and other birds, pets, and other animals: (a)

the goshawk (Accipiter gentilis), (b) red-tailed

hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), and (c) great horned

owl (Bubo virginianus).

Introduction

Hawks and owls are birds

of prey and are frequently referred to as raptors— a

term that includes the falcons, eagles, vultures, kites,

ospreys, northern harriers, and crested caracaras. Food

habits vary greatly among the raptors. Hawks and owls

are highly specialized predators that take their place

at the top of the food chain. Some are responsible for

the loss of poultry or small game. In the past, raptors

were persecuted through indiscriminate shooting,

poisoning, and pole trapping. The derogatory term

chicken hawk was used generically to identify raptors,

especially hawks, but has fallen out of usage during the

past two decades. Recently, many people have developed a

more enlightened attitude toward raptors and their place

in the environment.

People who experience

raptor damage problems should immediately seek

information and/or assistance. “Frustration killings”

occur far too often because landowners are unfamiliar

with or unable to control damage with nonlethal control

techniques. These killings result in the needless loss

of raptors, and they may lead to undesirable legal

actions. If trapping or shooting is necessary, permits

should be requested and processed as quickly as

possible. Always consider the benefits that raptors

provide before removing them from an area; their

ecological importance, aesthetic value, and

contributions as indicators of environmental health may

outweigh the economic damage they cause.

Identification and General Biology

There are two main groups

of hawks: accipiters and buteos. Accipiters are the

forest-dwelling hawks. North American species include

the northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis), Cooper’s hawk

(Accipiter cooperii), and sharp-shinned hawk (Accipiter

striatus). They are characterized by distinctive flight

silhouettes—relatively short, rounded wings and a long

rudderlike tail. Their flight pattern consists of

several rapid wing beats, then a short period of gliding

flight, followed by more rapid wing beats. Accipiters

are rarely seen except during migration because they

inhabit forested areas and are more secretive than many

of the buteos.

The largest and least

common, but most troublesome, accipiter is the goshawk

(Fig. 1). It is a bold predator that feeds primarily on

forest-dwelling rodents, rabbits, and birds.

Occasionally, it is attracted by free-ranging poultry or

large concentrations of game birds and can cause

depredation problems. Its breeding range is limited to

Canada, the northern United States, and the montane

forests of the western United States. Spectacular autumn

invasions of goshawks occur at irregular intervals in

the northern states. These are probably the result of

widespread declines in prey populations throughout the

goshawk’s breeding range. Cooper’s hawks will

occasionally cause problems with poultry; sharp-shinned

hawks are rarely a problem because of their small size.

The buteos are known as

the broad-winged or soaring hawks. They are the most

commonly observed raptors in North America. Typical

species include the red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis),

red-shouldered hawk (Buteo lineatus), broad-winged hawk

(Buteo platypterus), Swainson’s hawk (Buteo swainsoni),

rough-legged hawk (Buteo lagopus), and ferruginous hawk

(Buteo regalis). All buteos have long, broad wings and

relatively short, fanlike tails. These features enable

them to soar over open country during their daily

travels and seasonal migrations.

The red-tailed hawk (Fig.

1) is one of our most common and widely distributed

raptors. Redtails can be found over the entire North

American continent south of the treeless tundra and in

much of Central America. They demonstrate a remarkably

wide ecological tolerance for nesting and hunting sites

throughout their extensive range. Typical eastern

redtails nest in mature forests and woodlots, while in

the Southwest they often nest on cliffs or in trees and

cacti. Their diet, although extremely varied, usually

contains large numbers of rodents and other small

mammals. Redtails occasionally take poultry and other

livestock, but the benefits they provide in aesthetics,

as well as in the killing of rodents may outweigh

depredation costs. Other species of buteos rarely cause

problems.

Owls, unlike hawks, are

almost entirely nocturnal. Thus, they are far more

difficult to observe, and much less is known about them.

They have large heads and large, forward-facing eyes.

Their flight is described as noiseless and mothlike.

There are 19 species of owls in the continental United

States. They range in size from the tiny, 5- to 6-inch

(12-to 15-cm) elf owl (Micrathene whitneyi) that resides

in the arid Southwest, to the large, 24- to 33inch

(60-to 84-cm) great gray owl (Strix nebulosa) that

inhabits the dense boreal forests of Alaska, Canada, and

the northern United States.

The great horned owl (Bubo

virginianus, Fig. 1) is probably the most widely

distributed raptor in North America. Its range extends

over almost all the continent except for the extreme

northern regions of the Arctic. These large and powerful

birds are considered to be the nocturnal complement of

the red-tailed hawk. Great horned owls generally prey on

small-to medium-sized birds and mammals and will take

poultry and other livestock when the opportunity

presents itself. They are responsible for most raptor

depredation problems.

Damage and Damage Identification

The most troublesome

raptors are the larger, more aggressive species, such as

the goshawk, red-tailed hawk, and great horned owl. The

majority of depredation problems occur with free-ranging

farmyard poultry and game farm fowl. Chickens, turkeys,

ducks, geese, and pigeons are vulnerable because they

are very conspicuous, unwary, and usually concentrated

in areas that lack escape cover. Confined fowl that are

chased by raptors will often pile up in a corner,

resulting in the suffocation of some birds. Reproduction

may also be impaired in some fowl if harassment

persists.

For years, game farms have

dealt with raptor depredation problems. Large

concentrations of game farm animals are strong

attractants to predators. Operators should consider the

prevention of predation as part of their cost of

operation. Other depredation problems include the loss

of rabbits at beagle clubs, the loss of homing and

racing pigeons, and occasionally the loss of farm or

household pets. Cooper’s and sharp-shinned hawks

occasionally prey on songbirds that are attracted to

feeding stations. This should be viewed as a natural

event, however, and control of the raptors is not

advisable.

There are occasions when

raptors cause human safety and health hazards. For

example, concentrations of raptors at airports increase

the risk of bird-aircraft collisions and loss of human

life. The vast majority of aircraft strikes involve

gulls, starlings, and blackbirds, but a few raptor

strikes have been documented. It is interesting to note

that falconers with trained hawks have been used to

clear airport runways of other birds so that airplanes

can land. Although raptors are usually secretive and

choose to avoid human contact, they occasionally nest or

roost in close association with humans. At such times,

noise, property damage, and aggressive behavior at nest

sites can cause problems.

Poultry and other

livestock are vulnerable to a wide range of predators.

Frequent sightings of hawks and owls near the

depredation site may be a clue to the predator involved,

but these sightings could be misleading. When a

partially eaten carcass is found, it is often difficult

to determine the cause of death. In all cases, the

remains must be carefully examined. Raptors usually kill

only one bird per day. Raptor kills usually have bloody

puncture wounds in the back and breast from the bird’s

talons. Owls often remove and eat the head and sometimes

the neck of their prey. In contrast, mammalian predators

such as skunks or raccoons often kill several animals

during a night. They will usually tear skin and muscle

tissue from the carcass and cut through the feathers of

birds with their sharp teeth.

Hawks pluck birds, leaving

piles of feathers on the ground. Beak marks can

sometimes be seen on the shafts of these plucked

feathers. Owls also pluck their prey, but at times they

will swallow small animals whole. Many raptors

(especially red-tailed hawks and other buteos) feed on

carrion. The plucked feathers can often determine

whether a raptor actually killed an animal or was simply

“caught in the act” of feeding on a bird that had died

of other causes. If the feathers have small amounts of

tissue clinging to their bases, they were plucked from a

cold bird that died of another cause. If the base of a

feather is smooth and clean, the bird was plucked

shortly after it was killed.

Raptors often defecate at

a kill site. Accipiters such as the goshawk leave a

splash or streak of whitewash that radiates out from the

feather pile, whereas owls leave small heaps of chalky

whitewash on the ground.

Hawks and owls regurgitate

pellets that are accumulations of bones, teeth, hair,

and other undigested materials. These are not usually

found at the kill site, but instead accumulate along

with whitewash beneath a nearby perch or nest site.

Fresh pellets, especially of owls, are covered with a

moist iridescent sheen. They can be carefully teased

apart and examined to learn what the hawk or owl had

been eating. Owls gulp their food and swallow many bones

along with the flesh. These bones are only slightly

digested and persist in the pellets. A pellet that

contains large bones, such as those from the leg of a

rabbit, is undoubtably from a great horned owl. Hawks

feed more daintily and have stronger digestive juices

than owls. Thus, hawk pellets contain fewer bones.

Legal Status

All hawks and owls are

federally protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act

(16 USC, 703-711). These laws strictly prohibit the

capture, killing, or possession of hawks or owls without

special permit. No permits are required to scare

depredating migratory birds except for endangered or

threatened species (see Table 1), including bald and

golden eagles.

In addition, most states

have regulations regarding hawks and owls. Some species

may be common in one state but may be on a state

endangered species list in another. Consult your local

USDA-APHIS-Animal Damage Control, US Fish and Wildlife

Service (USFWS), and/or state wildlife department

representatives for permit requirements and information.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

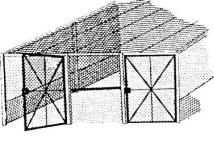

The ultimate

solution to raptor depredation is prevention.

Free-roaming farmyard chickens, ducks, and pigeons

attract hawks and owls and are highly susceptible to

predation. Many problems can be eliminated by simply

housing poultry at night. They can be conditioned to

move into coops or houses by feeding or watering them

indoors at dusk. If depredation persists, durable fenced

enclosures can be constructed by securing poultry wire

to a wooden framework and covering the enclosure with

poultry wire, nylon netting, or overhead wires (Fig. 2).

A double layer of overhead netting separated by a 5-to

6-inch (12- to 15-cm) space may be necessary to keep

owls away from penned birds. Large poultry operations

rarely have depredation problems because most practice

confinement.

Table 1. Federally

endangered or threatened raptors.

Name: California condor (Gymnogyps

californianus) Status: Endangered Where Endangered: US

(California and Oregon), Mexico (Baja California).

Name: Bald eagle (Haliaeetus

leucocephalus)

Status: Endangered and

Threatened

Where Endangered: US

(Conterminous states except Michigan, Minnesota, Oregon,

Washington, and Wisconsin)

Where Threatened: US

(Michigan, Minnesota, Oregon, Washington, and Wisconsin)

Name: American peregrine

falcon (Falco peregrinis anatum)

Status: Endangered

Where Endangered: Nests

from central Alaska across northcentral Canada to

central Mexico. Winters south to South America.

Name: American peregrine

falcon (Falco peregrinis tundrius)

Status: Threatened

Where Threatened: Nests

from northern Alaska to Greenland. Winters south to

Central and South America.

Name: Peregrine falcon (Falco

peregrinis) Status: Endangered Where Endangered:

Wherever found in wild in the conterminous 48 states.

Name: Hawaiian (lo) hawk (Buteo

solitarius) Status: Endangered Where Endangered: US

(Hawaii)

Name: Everglade (snail

kite) kite (Rostrhamus sociabilis plumbeus) Status:

Endangered Where Endangered: US (Florida)

Name: Palau owl (Pyroglaux

[=Otus] podargina) Status: Endangered Where Endangered:

West Pacific Ocean: US (Palau Islands)

Habitat Modification

Habitat modification can

make an area less attractive to raptors. Hawks and owls

often survey an area from a perch prior to making an

attack. Eliminate perch sites within 100 yards (90 m) of

the threatened area by removing large, isolated trees

and other perching surfaces. Install utility lines

underground and remove telephone poles near

poultry-rearing sites. Cap poles with sheet metal cones,

Nixalite®, Cat Claws®, or inverted spikes. Improve

rabbit escape cover at beagle clubs by constructing

brush piles and cutting large trees to increase the

density of shrub and ground cover. An abundance of

rabbits will often attract raptors. Clubs should release

only as many rabbits as are needed for an outing. Hawks

and owls that roost in buildings can be frightened away,

or live trapped and removed. Close off all entryways

after the birds are out of the building. Common barn

owls are endangered in some states and rarely, if ever,

cause damage to poultry. Their use of farm buildings,

where sanitation problems associated with droppings pose

no threat, should be encouraged. Consult your local

wildlife agency for information on barn owls in your

area.

Frightening

There are many techniques that can be used to scare

hawks and owls from an area where they are causing

damage. Some are inexpensive and easy to use, while

others are not. The effectiveness of frightening devices

depends greatly on the bird, area, season, and method of

application. Generally, if birds are hungry, they

quickly get used to and ignore frightening devices.

Frightening devices are usually a means of reducing

losses rather than totally eliminating them. Landowners

who use them must be willing to tolerate occasional

losses. Increasing human activity in the threatened area

will keep most raptors at a distance. The most common

and easily implemented frightening device is a shotgun

fired into the air in the direction of (not at) the

raptor. Scarecrows are effective at repelling raptors

when they are moved regularly and used in conjunction

with shotgun fire or pyrotechnics.

Pyrotechnics include a

variety of exploding or noise-making devices. The most

commonly used are shell crackers, which are 12-gauge

shotgun shells containing a firecracker that is

projected 50 to 100 yards (45 to 90 m) before it

explodes. Fire shell crackers in the direction of hawks

or owls that are found within the threatened area. An

inexpensive open-choke shotgun is recommended. Check the

gun barrel after each shot and remove any wadding from

the shells that may become lodged in the barrel. Noise,

whistle, and bird bombs are also commercially available.

They are fired from pistols and are less expensive to

use than shell crackers, but their range is limited to

25 to 75 yards (23 to 68 m). Your local fire warden can

provide information on local or state permits that are

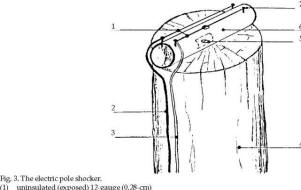

required to possess and use pyrotechnics. The electric

pole shocker is a device developed by R.W. Schmitt of

Sheboygan, Wisconsin, to protect game farms and poultry

operations (Fig. 3). It has proven very effective in

several different settings in Wisconsin. Each unit

consists of a ground wire running 1 inch (2.5 cm) from

and parallel to a wire that is connected to an electric

fence charger. Install electrical shocking units on top

of 14- to 16-foot (4- to 5-m) poles and erect the poles

around the threatened area at 50- to 100-foot (15- to

30-m) intervals. When a raptor lands on a pole, it

receives an electric shock and is repelled from the

immediate area. Other perching sites in the area should

be removed or made unattractive. Energize the shocking

unit only from dusk until dawn for owls and during

daylight hours for hawks. The electric pole shocker

keeps raptors from perching within a threatened area but

does not exclude them from nesting in or using a nearby

area. Most hawks and owls are highly territorial. A pair

that is allowed to remain will aggressively defend the

area and usually exclude other hawks and owls. Thus,

farmers may actually find it beneficial to coexist with

a pair of hawks or owls that have learned to avoid an

area protected by pole shockers.

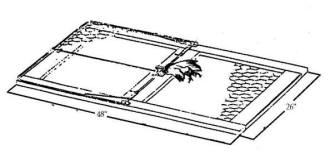

Fig. 2. A complete enclosure can protect fowl and

livestock from hawk and owl predation.

Fig. 3. The electric pole

shocker.

(1) uninsulated (exposed) 12-gauge (0.28-cm) copper,

ground, and hot wires (no connection from ground to hot

wire) (2) insulated wire to ground (3) insulated wire to

fence charger (4) 14- to 16-foot (4- to 5-m) post (5)

mounting screw (6) 1-inch x 6-inch (2.5- x 15-cm)

self-insulating plastic pipe (7) 3/4-inch (0.2-cm) sheet

metal screws with plastic expansion sleeve or tubing

between head of screw and plastic pipe

Repellents and Toxicants

No repellents

or toxicants are registered or recommended for

controlling hawk or owl damage. In years past, raptors

were killed by putting out carcasses laced with poison.

This practice led to the indiscriminate killing of many

nontarget animals. Concerns for human safety also

prompted the banning of toxicants for raptor control.

Trapping and Relocating

A landowner

must obtain a permit from the US Fish and Wildlife

Service and usually the local state wildlife agency to

trap any hawk or owl that is causing damage. Trapping is

usually permitted only after other nonlethal techniques

have failed. Set traps in the threatened area where they

can be checked at least twice a day. If possible,

experienced individuals or agency personnel should

conduct the trapping and handling of captured birds.

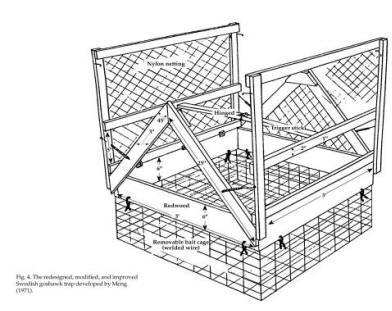

The Swedish goshawk trap

is a relatively large, semipermanent trap that can be

used to capture all species of hawks and owls (Fig. 4).

It consists of two parts: a 3 x 3 x 1-foot (90 x 90 x

30-cm) bait cage made of 1-inch (2.5-cm) mesh welded

wire. A trap mechanism consisting of a wooden “A” frame,

nylon netting, and a trigger mechanism is mounted on the

bait cage. A hawk or owl dropping into the trap will

trip the trigger mechanism and be safely trapped inside.

Pigeons make very good lures because they are hardy,

easily obtained, and move enough to attract hawks and

owls. Other good lures include starlings, rats, and

mice. For detailed information on the construction and

use of Swedish goshawk traps, see Meng (1971) and

Kenward and Marcstrom (1983).

The bal-chatri trap is a

relatively small, versatile trap that can be modified to

trap specific raptor species (Fig. 5). Live mice are

used to lure raptors into landing on the traps. Nylon

nooses entangle their feet and hold the birds until they

are released. The quonset-hut type bal-chatri was

designed for trapping large hawks and owls (Berger and

Hamerstrom 1962). The trap is made of 1-inch (2.5-cm)

chicken wire, formed into a cage that is 18 inches long,

10 inches wide, and 7 inches high at the middle (46 x 25

x 18 cm). The floor consists of 1-inch (2.5-cm) mesh

welded wire with a lure entrance door and steel rod

edging for ballast. The top is covered with about 80

nooses of 40-pound (18-kg) test monofilament fishing

line (Fig. 5). Pigeons, starlings, house mice, and other

small rodents can be used as lures. The trap should be

tied to a flexible branch or bush to keep a trapped bird

from dragging the trap too far and breaking the nylon

nooses.

Spring-net traps are ideal

for catching particular hawks or owls that are creating

a damage problem (Fig. 6). Square spring nets, hoop

nets, and the German “butterfly trap” have all been used

successfully. A trap is baited by attaching the

partially eaten carcass of a fresh kill or a stuffed

bird to the trigger bar. The trap should be camouflaged

by covering the frame and folded net with leaves and

feathers from the kill. For detailed information on

spring-net traps see Kenward and Marcstrom (1983).

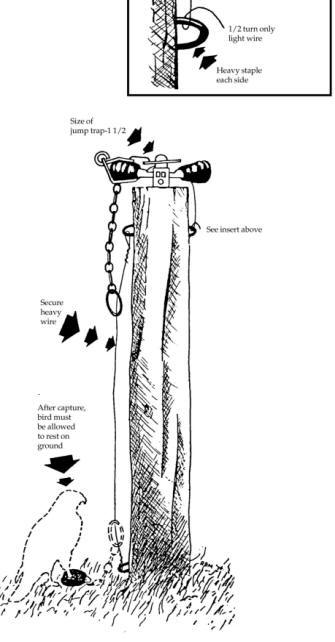

Problem

hawks and owls can be trapped safely using the sliding

padded pole trap because of their tendency to perch

prior to making an attack (Fig. 7). Erect 5- to 10-foot

(1.5- to 3-m) poles around the threatened area where

they can be seen easily and place one padded steel

leghold Problem

hawks and owls can be trapped safely using the sliding

padded pole trap because of their tendency to perch

prior to making an attack (Fig. 7). Erect 5- to 10-foot

(1.5- to 3-m) poles around the threatened area where

they can be seen easily and place one padded steel

leghold

trap (No. 1 1/2) on top of

each pole. The jaws must be well padded with surgical

tubing or foam rubber and wrapped with electrician’s

tape. Run a 12-gauge steel wire through the trap chain

ring and staple it to the top and bottom of the post.

This allows the trap to slide to the ground where the

bird can rest. Some states prohibit the use of pole

traps.

Fig. 4. The redesigned,

modified, and improved Swedish goshawk trap developed by

Meng (1971).

Handling and

Transportation. If necessary, landowners can safely

handle and transport hawks and owls. The key to

successful raptor handling is to control the bird’s

feet. The talons can easily grasp a careless hand and

inflict a painful injury. There is significantly less

chance of injury from the wings and beak. The safest

approach, regardless of the type of trap, is to toss an

old blanket or coat over both the bird and trap. The

darkness will calm Select a box that is large enough for

the bird to stand upright in. Holes should be punched

near the bottom of the box to supply fresh air and keep

the raptor from struggling toward any cracks of light

coming from the top of the box. Carry only one bird per

box. Tape an old rag or towel to the floor to provide a

good gripping surface to keep the bird from slipping. If

a burlap bag must be used to transport the bird, tie the

bird’s legs together with a nylon stocking to keep it

from footing someone during transport or release. If

possible, ask a local bird bander to attach a leg band.

Banding information can be very useful to the research

and management of raptors.

Transport the bird as

quickly and comfortably as possible.

Raptors

should be restrained before they are transported to

reduce the chances of injury to both the bird and

handler. The best transport container is a stout,

covered cardboard box. Minimize excess handling, and

above all, keep the bird calm and cool. More birds die

most of overheating during shipment than of any other

cause. Transport the bird as far away from the trapping

site as possible. Some biologists believe that 20 miles

(32 km) is sufficient, but raptors have been known to

travel up to 200 miles (320 ) km after release. If a

bird is trapped in the fall, help it along its way by

transporting it southward birds and make them less able

to defend themselves. Reach in carefully with your bare

hands and grasp the bird’s lower legs. Control the feet

to avoid getting “footed.” Pull the bird out of the trap

so that it is clear of any object on which it could

injure itself. Fold the wings down against the body and

hold them securely. Check the bird for any signs of

external injury, such as cut feet or legs, excessively

battered feathers, or scalping (the splitting of the

skin over the forehead). If the bird is injured, have a

local veterinarian examine it, or in extreme cases,

transport it to the nearest raptor rehabilitation

center. Raptors

should be restrained before they are transported to

reduce the chances of injury to both the bird and

handler. The best transport container is a stout,

covered cardboard box. Minimize excess handling, and

above all, keep the bird calm and cool. More birds die

most of overheating during shipment than of any other

cause. Transport the bird as far away from the trapping

site as possible. Some biologists believe that 20 miles

(32 km) is sufficient, but raptors have been known to

travel up to 200 miles (320 ) km after release. If a

bird is trapped in the fall, help it along its way by

transporting it southward birds and make them less able

to defend themselves. Reach in carefully with your bare

hands and grasp the bird’s lower legs. Control the feet

to avoid getting “footed.” Pull the bird out of the trap

so that it is clear of any object on which it could

injure itself. Fold the wings down against the body and

hold them securely. Check the bird for any signs of

external injury, such as cut feet or legs, excessively

battered feathers, or scalping (the splitting of the

skin over the forehead). If the bird is injured, have a

local veterinarian examine it, or in extreme cases,

transport it to the nearest raptor rehabilitation

center.

Fig. 6.Automatic spring-net trap in set position; inset

with bait.

Shooting

All hawks and

owls are protected by federal and state laws. There are

cases, however, in which they can create public health

and safety hazards or seriously affect a person’s

livelihood. Contact your local USDA-APHIS-ADC office

first if you are interested in obtaining a shooting

permit. The USFWS and state wildlife agencies may issue

shooting permits for problem hawks and owls if nonlethal

methods of controlling damage have failed or are

impractical and if it is determined that killing the

offending birds will alleviate the problem.

Permittees may kill hawks

or owls only with a shotgun not larger than 10-gauge,

fired from the shoulder and only within the area

described by the permit. Permittees may not use blinds

or other means of concealment, or decoys or calls that

are used to lure birds within gun range. Exceptions to

the above must be specifically authorized by USFWS. All

hawks or owls that are killed must be turned over to

USFWS personnel or their representatives for disposal.

Economics

of Damage and Control

In 1985, we conducted a

national survey of US Fish and Wildlife Service and

Cooperative Extension personnel. Nearly all noted that

the economic damage caused by raptors is minimal on a

national scale, but can be locally severe if depredation

occurs on fowl or livestock that are relatively valuable

and vulnerable. Cost estimates of damage ranged from $10

to $5,000 per report and from $70 to $94,000 per year.

The severity of raptor problems is influenced by several

factors, including prey and carrion abundance, weather,

time of year, husbandry methods, vegetative cover, and

topography as well as density and local distribution of

raptors.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank

Fran and Frederick N. Hamerstrom for their comments on

early manuscripts and information regarding the handling

of raptors. Reviewers included Richard H. Behm, James L.

Ruos, Leroy W. Sowl,

V. Dan Stiles, and Richard

Winters. Eldon L. McLaury reviewed the manuscript and

provided legal information.

Figure 1 by Elva

Hamerstrom Paulson, from Hamerstrom (1972).

Figure 2 from Salmon and

Conte (1981).

Figure 3 by the authors.

Figure 4 from Meng (1971).

Figure 5 from Berger and

Hamerstrom (1962).

Figure 6 from Kenward and

Marcstrom (1983).

Figure 7 from US

Department of Interior, Bulletin 211-1-77.

For Additional Information

Berger, D. D., and F. Hamerstrom. 1962. Protecting a

trapping station from raptor predation. J. Wildl.

Manage. 26:203-206.

Hamerstrom, F. 1972. Birds

of prey of Wisconsin. Wisconsin Dep. Nat. Resour. 64 pp.

Hamerstrom, F. 1984.

Birding with a purpose. Iowa State Univ. Press, Ames.

130 pp.

Heintzelman, D. S. 1979.

Hawks and owls of North America. Universe Books, New

York. 197 pp.

Karlbom, M. 1981.

Techniques for trapping goshawks. Pages 138-144 in R. E.

Kenward and I. Lindsay, eds. Understanding the goshawk,

Internat. Assoc. Falconry Conserv. Birds of Prey.

Kenward, R. E., and V.

Marcstrom. 1981. Goshawk predation in game and poultry:

some problems and solutions. Pages 152-162 in R. E.

Keward and I. Lindsay, eds. Understanding the goshawk.

Internat. Assoc. Falconry Conserv. Birds of Prey.

Kenward, R. E., and V.

Marcstrom. 1983. The price of success in goshawk

trapping. Raptor Res. 17:84-91.

Meng, H. 1971. The Swedish

goshawk trap. J. Wildl. Manage. 35:832-835.

Newton, I. 1979.

Population ecology of raptors. Buteo Books, Vermillion,

South Dakota. 399 pp.

Peterson, L. 1979. Ecology

of great horned owls and red-tailed hawks in

southeastern Wisconsin. Wisconsin Dep. Nat. Resour.

Tech. Bull. 111. Madison. 63 pp.

Salmon, T. P., and F. S.

Conte. 1981. Control of bird damage at aquaculture

facilities. WML No. 475. US Dep. Inter. Fish Wildl. Serv.,

Washington, D.C. 11 pp.

US Fish and Wildlife

Service. (no date). Raptor control-protecting livestock

from hawk and owl predation. US Dep. Inter. An. Damage

Control Bull. 211-1-77.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

E-62

01/08/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|