|

|

|

|

|

BIRDS: European Starlings |

|

|

Fig. 1. European starling,

Sturnus vulgaris

Identification

Starlings are robin-sized

birds weighing about 3.2 ounces (90 g). Adults are dark

with light speckles on the feathers. The speckles may

not show at a distance (Fig. 1). The bill of both sexes

is yellow during the reproductive cycle (January to

June) and dark at other times. Juveniles are pale brown

to gray.

Starlings generally are

chunky and hump-backed in appearance, with a shape

similar to that of a meadowlark. The tail is short, and

the wings have a triangular shape when outstretched in

flight. Starling flight is direct and swift, not rising

and falling like the flight of many blackbirds.

Range

Since their introduction

into New York in the 1890s, starlings have spread across

the continental United States, northward to Alaska and

the southern half of Canada, and southward into northern

Mexico. They are native to Eurasia, but have also been

introduced in South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and

elsewhere.

Habitat

Starlings are found in a

wide variety of habitats including cities, towns, farms,

ranches, open woodlands, fields, and lawns. Ideal

nesting habitat would include areas with trees or other

structures that have cavities suitable for nesting and

short grass (turf) areas or grazed pastures for

foraging. Ideal winter habitat would include areas with

structures and/or tall trees for daytime loafing

(resting) and nighttime roosting; and grazed pastures,

open water areas, and livestock facilities for foraging.

Food Habits

Starlings consume a

variety of foods, including fruits and seeds of both

wild and cultivated varieties. Insects, especially

Coleoptera and Lepidoptera lawn grubs, and other

invertebrates total about one-half of the diet overall,

and are especially important during the spring breeding

season. Other items including livestock rations and food

in garbage become an important food base for wintering

starlings.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

European starlings were

brought into the United States from Europe. They were

released in New York City in 1890 and 1891 by an

individual who wanted to introduce to the United States

all of the birds mentioned in Shakespeare’s works. Since

that time, they have increased in numbers and spread

across the country. They were first observed in Nebraska

in 1930, in Colorado in 1939, and in California in 1942.

The starling population in the United States is

estimated at 140 million birds.

Starlings nest in holes or

cavities almost anywhere, including tree cavities,

birdhouses, and holes in buildings or cliff faces.

Females lay 4 to 7 eggs which hatch after 11 to 13 days

of incubation. Young leave the nest when they are about

21 days old. Both parents help build the nest, incubate

the eggs, and feed the young. Sometimes 2 clutches of

eggs are laid per season, but most of the production is

from the first brood fledged.

Although starlings are not

always migratory, some will migrate up to several

hundred miles, while others may remain in the same

general area throughout the year. Hatching-year

starlings are more likely to migrate than adults, and

they tend to migrate farther.

Outside the breeding

season, starlings feed and roost together in flocks.

Starling and blackbird flocks often roost together in

urban landscape trees or in small dense woodlots or

overcrowded tree groves. They choose trees or groves

that offer ample perches so that all may roost together.

In colder weather they choose dense vegetation such as

coniferous trees or structures (such as barns, urban

structures) that provide protection from wind and cold.

Fall-roosting flocks are relatively small (from several

hundred to several thousand birds), but because they are

spread over large geographic areas, they can cause

widespread nuisance problems. In contrast,

winter-roosting flocks are large (sometimes exceeding 1

million birds), but are often confined to a few acres

(ha). Some of the winter roosting areas are occupied by

starlings year after year (Fig. 2). Each day they may

fly 15 to 30 or more miles (24 to 48 km) from roosting

to feeding sites. During the day when not feeding, they

may perch in smaller groups inside farm buildings or in

other warm, protected spots in and around urban

structures.

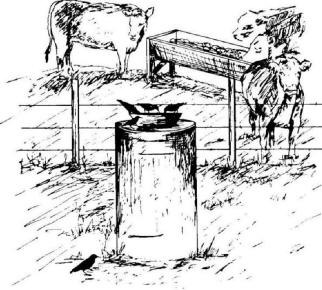

Damage and Damage Identification

Starlings are frequently

considered pests because of the problems they cause,

especially at livestock facilities (Fig. 3) and near

urban roosts. Starlings may selectively eat the

high-protein supplements that are often added to

livestock rations.

Starlings may also be

responsible for transferring disease from one livestock

facility to another. This is of particular concern to

swine producers. Tests have shown that the transmissible

gastroenteritis virus (TGE) can pass through the

digestive tract of a starling and be infectious in the

starling feces. Researchers, however, have also found

healthy swine in lots with infected starlings. This

indicates that even infected starlings may not always

transmit the disease, especially if starling interaction

with pigs is minimized. TGE may also be transmitted on

boots or vehicles, by stray animals, or by infected

swine added to the herd. Although starlings may be

involved in the spread of other livestock diseases,

their role in transmission of these diseases is not yet

understood.

Starlings cause other

damage by consuming cultivated fruits such as grapes,

peaches, blueberries, strawberries, figs, apples, and

cherries. They were recently found to damage ripening

(milk stage) corn, a problem primarily associated with

blackbirds. In

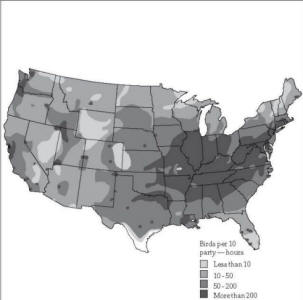

Fig. 2. Starling wintering

areas, 1972. Map by J. W. Rosahn, based on the National

Audubon Society’s annual Christmas Bird Count.

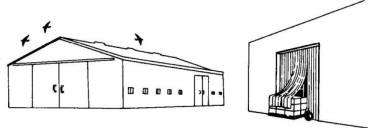

Fig. 3. At livestock facilities such as this pig

operation, European starlings consume feed, contaminate

feed and water with their droppings, and may transmit

disease.

some areas starlings pull

sprouting probe for grubs, but the frequency and grains,

particularly winter wheat, and extent of such damage is

not well eat the planted seed. Starlings may documented.

damage turf on golf courses as they The growing

urbanization of wintering starling flocks seeking warmth

and shelter for roosting may have serious consequences.

Large roosts that occur in buildings, industrial

structures, or, along with blackbird species, in trees

near homes are a problem in both rural and urban sites

because of health concerns, filth, noise, and odor. In

addition, slippery accumulations of droppings pose

safety hazards at industrial structures, and the acidity

of droppings is corrosive.

Starling and blackbird

roosts located near airports pose an aircraft safety

hazard because of the potential for birds to be ingested

into jet engines, resulting in aircraft damage or loss

and, at times, in human injuries. In 1960, an Electra

aircraft in Boston collided with a flock of starlings

soon after takeoff, resulting in a crash landing and 62

fatalities. Although only about 6% of bird-aircraft

strikes are associated with starlings or blackbirds,

these species represent a substantial management

challenge at airports.

One of the more serious

health concerns is the fungal respiratory disease

histoplasmosis. The fungus Histoplasma capsulatum may

grow in the soils beneath bird roosts, and spores become

airborne in dry weather, particularly when the site is

disturbed. Although most cases of histoplasmosis are

mild or even unnoticed, this disease can, in rare cases,

cause blindness and/or death. Individuals who are

weakened by other health conditions or who do not have

endemic immunity are at greater risk from histoplasmosis.

Starlings also compete

with native cavity-nesting birds such as bluebirds,

flickers, and other woodpeckers, purple martins, and

wood ducks for nest sites. One report showed that, where

nest cavities were limited, starlings had severe impacts

on local populations of native cavity-nesting species.

One author has speculated that competition with

starlings may cause shifts in red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes

carolinus) nesting from urban habitats to rural forested

areas where starling competition is less.

Legal Status

European starlings are not

protected by federal law and in most cases not by state

law. Laws vary among states, however, so check with

state wildlife officials before beginning a control

program. In addition, state or local laws may regulate

or prohibit certain control techniques such as shooting

or the use of toxicants.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Close all

openings larger than 1 inch (2.5 cm) to exclude

starlings from buildings or other structures. This is a

permanent solution to problems inside the structure

(Fig. 4). Heavy plastic (polyvinyl chloride, PVC) or

rubber strips hung in open doorways of farm buildings

have been successful in some areas in excluding birds

while allowing people, machinery, or livestock to enter.

Hang 10-inch (25-cm) wide strips with about 2.0-inch

(5-cm) gaps between them. These strips might also be

useful for protecting feed bunks. Netting over doorways

may also exclude birds from buildings, but would be

easily torn by machinery or livestock.

Where starlings are

roosting or nesting on the ledge of a building, place a

wooden, metal, or plexiglass covering over the ledge at

a 45o angle to prevent use (Fig. 5). Metal protectors or

porcupine wires (Nixalite® and Cat Claw®) are also

available for preventing roosting on ledges or roof

beams.

Nylon or plastic netting

is another option for exclusion (Fig. 6). Exclude

starlings that are roosting inside open farm buildings

by covering the underside of the roof beams with

netting. Netting is also useful for covering fruit crops

such as cherries or grapes to prevent bird damage, and

studies show it to be a cost-effective method of

protecting higher-value grapes in commercial vineyards.

For wine grapes harvested one time per season,

tractor-mounted rollers can facilitate installation and

removal of netting draped directly over vines. Some New

York vineyards have used this method for five years with

the original netting still in good condition. For table

grapes harvested by hand several times per year, a frame

can be used to hold the netting above the vines so it

doesn’t interfere with the frequent harvests. A

practical tip: if protecting the total vineyard is

impractical, protect varieties that receive the most

damage, those that ripen early or are otherwise highly

attractive to birds (for example, small, dark, sweet

grapes.)

Fig. 4. Bird-proof buildings to permanently eliminate

bird problems inside.

Fig. 5. A wooden, metal, or plexiglass covering over a

ledge at a 45° angle (a) or porcupine wires (b) can be

used to prevent roosting and nesting.

Fig. 6. Netting can be used to exclude birds from

building rafters and from fruit trees.

Where starlings compete

with other birds for nest boxes, proper nest box

construction helps. For bluebird boxes, use a round 1

1/2-inch (3.8-cm) hole or a rectangular slot, 4 inches

(10 cm) wide by 1 1/8 inches (29 mm) high, to allow

bluebirds in but keep starlings out. Starlings are

discouraged by horizontal wood duck nest boxes made from

a 24-inch (61-cm) section of 12-inch-diameter (30.5-cm)

stove pipe. The ends are made from wooden circles, and

the entrance hole on one end is semicircular and 4

inches (10 cm) high by 11 inches (28 cm) wide. Other

nest box features such as interior dimensions and color,

amount of light allowed into the box, and box placement

appear to have potential for discouraging starlings

while encouraging preferred cavity-nesters.

Cultural Methods and Habitat Modification

Livestock Facilities.

Starlings are attracted to livestock operations by the

food and water that is available to them. Feedlots offer

an especially attractive food source to starlings during

winter when snow cover and frozen ground impede their

normal feeding in open fields or other areas. The snow

cover and frozen ground increase the likelihood as well

as the severity of damage.

Some livestock operations

are more attractive to starlings than others. Operations

that have large quantities of feed always available,

especially when located near a starling roost, are the

most likely to have damage problems. Research results

emphasize the importance of farm management practices in

long-term starling control. These practices limit the

availability of food and water to starlings, thus making

the livestock environment less attractive to birds. The

following practices used singly, but preferably in

combination, will reduce feed losses, the chance of

disease transmission, and the cost and labor of

conventional control measures.

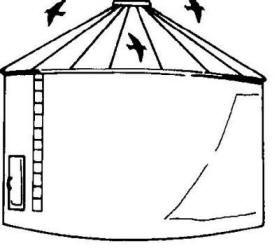

Fig.

7. Use bird-proof facilities to store grain. Fig.

7. Use bird-proof facilities to store grain.

1. Clean up spilled grain.

2. Store grain in bird-proof facilities (Fig. 7).

3. Use bird-proof livestock feeders. These include

flip-top pig feeders, lick wheels for liquid cattle

supplement, and automatic-release feeders (magnetic or

electronic) for costly high-protein rations. Using

covered feeders prevents starling access and

contamination of the food source, and the banging of the

lift-top lids as pigs use the feeders may frighten

starlings and keep them uneasy. Avoid feeding on the

ground because this is an open invitation to starlings.

-

Where possible, feed

livestock in covered areas such as open sheds

because these areas are less attractive to

starlings.

-

Use feed forms that

starlings cannot swallow, such as cubes or blocks

greater than 1/2 inch (1.3 cm) in diameter. Minimize

use of 3/16 inch (0.5 cm) pellets; starlings consume

these six times faster than granular meal.

-

When feeding protein

supplements with other rations, such as silage, mix

them well to limit starling access to the

supplements.

-

Where possible, adjust

feeding schedules so that exposure of feed to birds

is minimized. For example, when feeding once per

day, such as in a limited energy-feeding program for

gestating sows, delay the feeding until late in the

afternoon when foraging by starlings is decreased.

Feed cattle at night if possible.

-

Starlings prefer to

feed early to midday and in areas where feed is

constantly available. Feeding schedules that take

these factors into account minimize problems.

Starlings are especially attracted to water. Drain

or fill in unnecessary water pools around livestock

operations. Where feasible, control the water level

of livestock waterers to make them unavailable or

less attractive to starlings (Fig. 8).

Tree Roosts. When

roosts occur in a small number of landscape trees near

homes or along streets, thinning branches from the trees

used by birds will usually disperse them. Roosts in tree

groves or woodlots usually occur in dense, overcrowded

stands of young trees. Remove about one-third of the

trees to improve the tree stand, especially if marked by

a professional forester, and to disperse the birds. Such

thinning successfully dispersed roosts from research

woodlots in Ohio and Kentucky, and from at least two

problem-roost situations in Nebraska. In dense cedar

thickets, bulldozing strips through the roost to remove

one-third of the habitat has also been successful in

dispersing birds. Soil disturbance, however, may be

hazardous if soils harbor fungal spores of the human

respiratory disease histoplasmosis. For further

information on roost dispersal, see Bird Dispersal

Techniques.

Frightening

Frightening is

effective in dispersing starlings from roosts,

small-scale fruit crops, and some other troublesome

sites. It is useful around livestock operations that

have warm climates year-round, and where major

concentrations of wintering starlings exist. In the

central states, starlings concentrate at livestock

facilities primarily during cold winter months when snow

covers natural food sources. At this time, baiting and

other techniques are generally more effective than

frightening. In addition, frightening starlings may

disperse birds to other livestock facilities, a negative

point that should be considered if disease transfer is a

concern.

Frightening devices

include recorded distress or alarm calls, gas-operated

exploders, battery-operated alarms, pyrotechnics (shellcrackers,

bird bombs), chemical frightening agents (see Avitrol®

below), lights (for roosting sites at night), bright

objects, and various other stimuli. Some novel visual

frightening devices with potential effectiveness are

eye-spot balloons, hawk kites, and mylar reflective

tape. Ultrasonic (high frequency, above 20 kHz) sounds

are not effective in frightening starlings and most

other birds because, like humans, they do not hear these

sounds.

Harassing birds throughout

the evening as they land can be effective in dispersing

bird roosts if done for three to four consecutive

evenings or until birds no longer return. Spraying birds

with water from a hose or from sprinklers mounted in the

roost trees has helped in some situations. Beating on

tin sheets or barrels with clubs also scares birds. A

combination of several scare techniques used together

works better than a single technique used alone. Vary

the location, intensity, and types of scare devices to

increase their effectiveness. Two additional tips for

successful frightening efforts: 1) begin early before

birds form a strong attachment to the site, and 2) be

persistent until the problem is solved. For a more

detailed discussion of frightening techniques, see Bird

Dispersal Techniques.

Avitrol®. Avitrol® (active

ingredient: 4-aminopyridine) is a Restricted Use

Pesticide available in several bait formulations for use

as a chemical frightening agent. It is for sale only to

certified applicators or persons under their direct

supervision and only for those uses covered by the

applicator’s certification.

Avitrol® baits contain a

small number of treated grains or pellets mixed with

many untreated grains or pellets. Birds that eat the

treated portion of the bait behave erratically and/or

give warning cries that frighten other birds from the

area. Generally, birds that eat the treated particles

will die. Avitrol® baits are available for controlling

starlings at feedlots and structures. At the dilution

rates registered for use at feedlots, there is a low but

potential hazard to nontarget hawks and owls that might

eat birds killed by Avitrol®. It is therefore important

to pick up and bury or incinerate any dead starlings

found.

Around livestock

operations, Avitrol® is sometimes used where the goal is

to frighten or disperse the birds rather than to kill

them. However, many birds may be killed, and data are

lacking on whether the results of Avitrol® use at

feedlots occur because of frightening aspects or from

direct mortality.

Three Avitrol®

formulations are labeled for starling control at

feedlots (Pelletized Feed, Double Strength Corn Chops,

and Powder Mix). The formulation most appropriate for a

given situation may vary, particularly if large numbers

of blackbirds are mixed with the starlings. However, the

Pelletized Feed formulation is generally recommended for

starling control because starlings usually prefer

pellets over cracked corn (corn chops). The Double

Strength Corn Chops formulation is probably best for

mixed flocks of starlings and blackbirds. Because

Avitrol® is designed as a frightening agent, birds can

develop bait shyness (bait rejection) fairly quickly.

Prebaiting for several days with untreated pellets may

be necessary for effective bait consumption and control.

If starling problems persist, changing bait locations

and additional prebaiting may be needed. If any Avitrol®

baits are to be used, contact a qualified person trained

in bird control work (someone from USDA-APHIS-ADC or

Cooperative Extension, for example) for technical

assistance.

Repellents

Soft, sticky

repellents such as Roost-No-More®, Bird Tanglefoot®,

4-The-Birds®, and others consist of polybutenes, a

nontoxic material that can be useful in discouraging

starlings from roosting on sites such as ledges, roof

beams, or shopping-center signs. It is often helpful to

first put masking tape on the surface needing

protection, then apply the repellent onto the tape; this

increases effectiveness on porous surfaces and makes

removal easier. Over time, these materials lose their

effectiveness and have to be replaced.

Recent research has found

that flavoring used in grape soft drinks, dimethyl

anthranilate (DMA), and methyl anthranilate (MA) repel

starlings from livestock feed at rates that do not

affect cattle. Although subsequent field trials showed

that DMA may not be cost-effective in some situations,

results have indicated that MA has potential for

cost-effective starling repellency.

Research is ongoing to

improve the cost-effectiveness of this compound and to

develop its potential for managing starlings at

livestock facilities and possibly for repelling birds

from fruit crops.

Toxicants

When using

toxicants or other pesticides, always refer to the

current pesticide label and follow its instructions as

the final authority on pesticide use.

Starlicide. A chemical

compound developed for starling control during the 1960s

by the Denver Wildlife Research Center is now

commercially available as a pelletized bait. It is sold

under the trade name Starlicide Complete (0.1% 3-chloro

p-toluidine hydrochloride).

Starlicide is a

slow-acting toxicant for controlling starlings and

blackbirds around livestock and poultry operations. It

is toxic to other types of birds in differing amounts,

but will not kill house (English) sparrows (Passer

domesticus) at registered levels. Mammals are generally

resistant to its toxic effects.

Poisoned birds experience

a slow, nonviolent death. They usually die from 1 to 3

days after feeding, often at their roost. Generally, few

dead starlings will be found at the bait site. Poisoned

starlings are not dangerous to scavengers or predators.

However, to provide good sanitation and to prevent the

spread of diseases that the birds may carry, pick up and

bury or incinerate any dead starlings.

It is important to use

fresh bait, as the current formulation of Starlicide

Complete loses effectiveness in storage. Bait kept on

hand from one winter to the next may lose some of its

potency, and bait kept for 2 years may not work at all.

How to Use. Field

tests in both the western and eastern United States have

established guidelines for using Starlicide. For the

best success in a control program, we recommend the

following steps:

1. Observe birds feeding

in and around the livestock operation. Note the number

of starlings and when and where they prefer to feed. The

best time for observing is usually during the first few

hours following sunrise when birds are seeking their

morning meal.

-

Determine what species

of birds are feeding. If any protected birds, such

as doves, quail, pheasants, or songbirds, are

present, do not apply toxic bait. For assistance or

advice on bird identification or nontarget risk

assessment based on the situation, contact your

local Cooperative Extension office, USDA-APHIS-ADC

office, or the state wildlife agency.

-

Prebait, for best

results, with a nonpoisonous bait to accustom

starlings to feeding on bait at particular

locations. Place the prebait in areas where the

starlings concentrate to feed, but where it will not

be accessible to livestock or other nontarget

animals. The best prebait is a high-quality food

that resembles the toxic bait in color, size, and

texture. If such prebait is unavailable, use a good

quality feed such as that normally fed to livestock.

Prebait for 1 to 4 days

until the birds readily feed on the prebait. If good

consumption is not obtained, move the prebait to another

location where starlings are concentrating to feed.

-

Apply prebait and bait

on cold days when snow covers the ground. This

timing is more effective because starlings become

stressed for food and concentrate in livestock

feeding areas.

-

Place prebait and bait

in containers to ensure proper bait placement and to

protect it from the weather (Fig. 9). Black rubber

calf feeder pans work well. They do not tip easily,

their dark color does not frighten birds, and bait

is openly exposed. Empty farm wagons, feeder lids

turned upside down, wooden troughs, or other

containers may also work. Avoid brightly colored or

shiny containers or ones that might tip and spill

bait. At night, the containers can be covered to

protect the bait from the weather. However, they

must be uncovered at dawn so that starlings can feed

as soon as they arrive. At feedlots where large

numbers of starlings (more than 100,000) are

involved, and where large quantities of feed are

available on the ground, broadcasting bait in

alleyways as per label directions is recommended.

Fig. 9. Well-positioned

bait containers, excluded from livestock, provide better

safety and control in baiting programs for starlings.

-

Apply toxic bait after

starlings feed readily on the prebait by removing

all prebait and replacing it with the toxic bait.

Consult the label directions for the amount to use

(1 pound [0.45 kg] of Starlicide Complete used

properly will kill about 100 to 200 starlings). The

total number of starlings using a farm over a long

period of time may greatly exceed the numbers

observed on a given day, so continue baiting for at

least 2 or 3 days or until bait consumption

diminishes. Bait should be available to the

starlings at all times when they are present.

-

Good bait acceptance

may be more difficult to obtain in warm-weather

climates such as in the southernmost states. If this

occurs, and the Starlicide Complete bait is not

eaten, an alternative may be to use Starlicide

Technical (98% active ingredient) applied to baits

such as french-fried potatoes, small fruits, or

livestock feed according to label directions. The

french fries and fruits may be more attractive to

starlings, but they can spoil rapidly. Generally,

livestock feed makes an acceptable bait because

starlings are accustomed to feeding on it.

Starlicide Technical can be used only by or under

supervision of the USDA-APHIS-ADC for control of

blackbirds and starlings at livestock operations.

Contact them for help.

-

Remove bait after bait

consumption diminishes. Observe any birds arriving

at the feedlot during the next 2 to 3 mornings after

baiting. Reduced bird numbers at this time indicate

control, as most birds will die at the roost. If

starlings continue to be present, or if they

gradually return in increasing numbers, wait until a

number of birds are regularly returning to feed at

the area. Then apply prebait and toxic bait (Steps 4

to 6) as before. Do not leave Starlicide baits

exposed for prolonged periods because this may cause

bait shyness (bait rejection), and may also increase

hazards to protected bird species.

-

Group baiting may

increase effectiveness. Consider coordinating

control efforts with your neighbors. Several persons

baiting at the same time will produce better control

because starlings may forage over a large

geographical area and may change feeding sites from

day to day. Notify local wildlife officials of your

plans so that if large numbers of starlings are

removed, the officials will be able to explain the

die-off. Contact USDA-APHIS-ADC officials about the

possibility of using roost control procedures if a

large roost is associated with the damage problem.

9. Cautions: Starlicide is

poisonous to chickens, turkeys, ducks, and some other

birds. Never expose bait where poultry, livestock, or

nontarget wildlife can feed on it. Do not repackage

pesticides into anything other than their original

containers. Read and follow all label directions.

Toxic Perches.

Toxic perches are perforated metal tubes 24 or 27 inches

(61 or 69 cm) long containing a wick saturated with a

contact toxicant that enters the feet as the birds perch

on the tube. They can be safely and effectively used in

certain industrial and other structural roost situations

where they do not present hazards to nontarget birds and

avian predators such as hawks and owls. All killed birds

should be picked up immediately and buried or burned

because of potential hazards to other wildlife.

The active ingredient in

toxic perches, fenthion (Rid-A-Bird Perch 1100

Solution), is federally registered as a Restricted Use

Pesticide for use in these perches. Fenthion is rapidly

absorbed through the skin and should be used with

caution to avoid spillage and exposure to the handler.

It is toxic to humans, birds, fish, and aquatic

invertebrates. For additional information on fenthion,

refer to Pesticides.

Agents for Roost

Control. Roost control has been used to reduce

starling damage at livestock feedlots and in urban areas

where there are human health and sanitation concerns. A

recent study indicates, however, that roost control with

wetting agents (no longer registered) may not

consistently provide long-term reduction of birds at

feedlots, despite mostly favorable results in reducing

urban problems. The presence of other roosting

populations near the treated roost may be an important

factor. At urban sites having mild winter climates, the

accumulation of bird carcasses can produce a severe odor

and fly problem if carcasses are not picked up or buried

at the site soon after roost treatment. Bulldozing sites

is the most efficient method to bury carcasses, but soil

disturbance during this process may present human health

hazards from dissemination of histoplasmosis spores.

Such roost control should be considered only as a last

resort when other alternatives are not likely to solve

the problem in livestock and urban roost situations.

Currently, the only

material registered for roost control is Starlicide

Technical, which is used for baiting at or near roost

sites in areas where starlings congregate before

roosting. This method is currently registered for use in

only a few states and only under supervision of

USDA-APHIS-ADC personnel. A federal registration is

pending. Although this method of roost control is

labor-intensive, it has been effective.

Fumigants

Fumigation is

generally not practical for starling control, and no

fumigants are registered for this purpose.

Trapping Trapping

Trapping and

removing starlings can be a successful method of control

at locations where a resident population is causing

localized damage or where other techniques cannot be

used. An example is trapping starlings in a fruit

orchard.

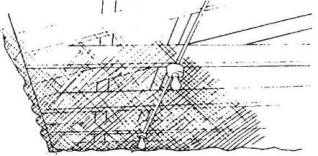

Two types of traps,

nest-box and decoy traps, are commonly used. Nest-box

traps (Fig. 10) are successful only during the nesting

season, whereas decoy traps (Fig. 11) are most effective

during other times when the birds are flocking.

Nontarget birds captured in traps should be immediately

released unharmed.

Decoy traps for starlings

should be at least 5 to 6 feet (1.5 to 1.8 m) high to

allow for servicing and can be quite large (for example,

10 feet [3 m] wide by 30 feet [9 m] long). A convenient

size is 6 x 8 x 6 feet (1.8 x 2.4 x 1.8 m) (Fig. 11). If

desired, the sides and top can be constructed in panels

to facilitate transportation and storage. In addition,

decoy traps can be set up on a farm wagon and thereby

moved to the best places to catch starlings. Place traps

where starlings are likely to congregate. Leave a few

starlings in the trap as decoys; their feeding behavior

and calls attract other starlings that are nearby. Decoy

birds in the trap must be well watered (which may

include a bird bath) and fed. A well-maintained decoy

trap can capture 100 or more starlings per day depending

on its size and location, the time of year, and how well

the trap is maintained. Euthanize captured starlings

humanely such as by carbon dioxide exposure or cervical

dislocation.

Shooting

Shooting is

more effective as a dispersal technique than as a way to

reduce starling numbers. The number of starlings that

can be killed by shooting is very small in relation to

the number of starlings usually involved in pest

situations. Shooting, however, can be helpful to

supplement and reinforce other dispersal techniques. For

more detail on dispersal, see Bird Dispersal Techniques.

Economics of Damage and Control

Consumption of livestock

feed by starlings can at times be a substantial economic

consideration. Data reported in 1968 from Colorado

feedlots estimated the cost of cattle rations consumed

during winter by starlings at $84 per 1,000 starlings.

Current feed costs and the associated losses would

certainly be much higher. A 1967 report indicated that 1

million starlings at a California feedlot resulted in

losses of $1,000 per day because of food consumption and

contamination, and starling interference with cattle

feeding Fig. 11. Starling decoy trap: (a) assembled view

and (b) details of the entrance panel. Side and end

activity. Another report estimated panels are covered

with wire on the outside; top panels are covered on the

inside of the frame.

that starlings in Idaho

consumed 15 to 20 tons (13.5 to 18 mt) of cattle feed

per day. A 1978 study in England estimated that the food

eaten by starlings in a calf-rearing unit over three

winters was 6% to 12% of the food presented to the

calves. Two other studies in England since then found 4%

losses and negligible damage, respectively.

Producers who wish to

estimate feed losses to starlings at their facilities

can do so using one of two methods. The following

equation, which was developed from data in Colorado,

estimates the cost of feed consumed per day:

Cost of feed ration

consumed per day = estimated starlings (to the nearest

1,000) x fraction of birds using trough x cost of feed

ration per pound (0.4536 kg) x 0.0625 pound (0.02813 kg)

consumed per starling per day.

A second method, which may

be applicable to most geographic areas, precludes the

need of estimating starling populations. It requires the

operator to observe the feed troughs several times

during the day and estimate the number of starlings

entering the troughs per day. From this estimate the

cost of the feed ration consumed per day can be

estimated with the following equation:

Cost of feed ration

consumed per day = estimated starling entries into

troughs x 0.0033 pounds (0.0015 kg) consumed per

starling entry x cost of feed ration per pound (0.4536

kg). These losses projected over a 3-to 4-month damage

season can assist in evaluating the costs and benefits

of proposed control measures.

Feed contamination from

starling excreta may not be an economic loss for cattle

or pig operations. In 2 years of testing at Western

Kentucky University, neither pigs nor cattle were

adversely affected by long-term exposure to feed heavily

contaminated with starling excreta. As compared to

controls, no significant differences were observed in

weight gain or feed efficiency (ratio of weight gain to

weight of feed offered). In addition, there were no

observed differences in feed rejection or disease

incidence. These results indicate that there is no

economic justification for starling control based solely

on feed contamination. However, the effects of livestock

water contamination from starling excreta have not been

well studied.

Starling interference with

livestock feeding patterns may have economic importance.

A study in England reported that calves in pens

protected from starlings showed higher growth rates and

better feed conversion than those in unprotected pens.

This protection led to an increased profit margin. The

difference observed, however, might have been caused by

starlings in the unprotrected pens consuming the calf

food, especially the high protein portion, rather than

by actual interference with the calf feeding.

The costs associated with

starlings in the spread of livestock disease may at

times be substantial. For example, during the severe

winter of 1978-1979, a TGE outbreak occurred in

southeast Nebraska, with over 10,000 pigs lost in 1

month in Gage County alone. Starlings were implicated

because the TGE outbreak was concurrent with large

flocks of starlings feeding at the same facilities. More

recent data show that starlings are capable of carrying

this disease in their feces. The role of starlings in

disease transfer, however, needs further study.

Bird damage to grapes in

the United States was estimated to be at least $4.4

million in 1972; starlings were one of the species

causing the most damage. Starlings, as well as many

other species of birds, also damage ripening cherry

crops. A 1972 study in Michigan found 17.4% of a total

crop lost to birds. A 1975 study in England estimated

damage at 14% (lower branches) to 21% (tree canopy) of

the crop; similar 1976 data showed less damage. Starling

damage to winter wheat in a study of 218 fields in three

regions in Kentucky and Tennessee averaged 3.8%, 0.5%,

and 0.4% respectively, with the most serious losses

(more than 14%) occurring where wheat was planted late

and fields were within 11 miles (16 km) of a large

starling roost.

Human health and safety

problems associated with urban starling roosts include

concerns about the disease histoplasmosis and about

aircraft-bird collisions. Although serious problems

occur only infrequently, they can have grievous

consequences where loss of human life and/or permanent

disability may occur. Moreover, equipment repair and

replacement costs associated with aircraft-bird

collisions can be substantial. For example, the costs of

aircraft-bird collisions in the United States are

estimated to be at least $20 million per year to

commercial aircraft and $10 million per year to Air

Force aircraft. These consequences mandate a thorough

understanding of urban roost situations and timely roost

management where the potential for human health and

safety problems exists.

On the beneficial side,

starlings eat large quantities of insects and other

invertebrates, especially during spring. Many of these

invertebrates, such as lawn grubs, are considered to be

pests. This benefit, however, is partially offset by the

fact that starlings often take over nest cavities of

native insect-eating birds. As trends move toward lower

pesticide use and sustainable, low-input turf and

agricultural systems, the role of starlings and other

birds may become more important. Research is needed to

further understand potential positive impacts of

starlings and to learn how to maximize potential

benefits while minimizing problems.

Although starlings are

frequently associated with damage problems, some of

which clearly cause substantial economic losses, the

economics of damage in relation to the cost and

effectiveness of controls are not well understood.

Several factors contribute to this: (1) Starlings are

difficult to monitor because they often move long

distances daily from roost to feeding areas, and many

migrate. (2) Effectiveness of controls, particularly in

relation to the total population in an area, is

difficult to document. For example, does population

reduction in a particular situation reduce the problem

or merely allow an influx of starlings from other areas,

and how does this vary seasonally or annually? In

addition, does lethal control just substitute for

natural mortality or is it additive?

(3) The economics of

interactions with other species are difficult to

measure. For example, how much is a bluebird or flicker

worth, and what net benefits occur when starling

interference with native cavity-nesting birds is

considered? (4) Other factors such as weather and

variation among problem situations complicates accurate

evaluation of damage and the overall or long-term

effectiveness of controls. These points, as well as

others mentioned in this chapter, are examples of

factors that must be considered in assessing the total

economic impact of starlings. Clearly, to minimize

starling-human conflicts we need a better understanding

of starlings and their interactions with various

habitats and control measures.

Acknowledgments

The references listed

under “For Additional Information” and many others were

used in preparing this chapter. Gratitude is extended to

the authors and the many researchers and observers who

contributed to this body of knowledge. We also thank M.

Beck, J. Besser, R. Fritschen, D. Mott, A. Stickley, and

R. Timm for comments on the first edition of this

chapter, J. Andelt provided typing and technical

assistance. We gratefully acknowledge M. Beck, R. Case,

D. Mott, and A. Stickley for critical reviews of this

second edition, and L. Germer, J. Gosey, and D. Reese

for reviews of specific portions.

Figure 1 from US Fish and

Wildlife Service (1974), “Controlling Starlings,”

Bulletin AC 209, Purdue University, West Lafayette,

Indiana, modified and adapted by Renee Lanik, University

of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Figure 2 from Bystrak et

al. (1974), used with permission. Figure copyrighted by

the National Audubon Society, Inc. Adapted by David

Thornhill. Map by J. W. Rosahn, based on the National

Audubon Society’s annual Christmas Bird Count. Map

reprinted by permission from “Wintering Areas of Bird

Species Potentially Hazardous to Aircraft.” D. Bystrak

et al. (1974), National Audubon Society, Inc.

Figure 3 photo by Ron J.

Johnson.

Figures 4 and 7 by Renee

Lanik based on drawings by Jon Eggers and a drawing from

Salmon and Gorenzel’s chapter “Cliff Swallows” in this

publication.

Figure 5 by Renee Lanik,

University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Figure 6 by Jill Sack

Johnson.

Figures 8 and 9 by Renee

Lanik, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Figure 10 from DeHaven and

Guarino (1969), adapted by Jill Sack Johnson.

Figure 11 by Renee Lanik

based on E. R. Kalmbach (1939), “The Crow in Its

Relation to Agriculture,” US Dep. Agric. Farmer’s Bull.

No. 1102, rev. ed., Washington, DC. 21 pp., and US Fish

Wildl. Serv. (no date), “Trapping Starlings,” Bull. AC

210, Purdue Univ., West Lafayette, Indiana.

For Additional Information

Aubin, T. 1989. The role

of frequency modulation in the process of distress calls

recognition by the starling (Sturnus vulgaris). Behav.

108:57-72.

Barnes, T. G. 1991.

Eastern bluebirds, nesting structure design and

placement. College of Agric. Ext. Publ. FOR-52, Univ.

Kentucky, Lexington. 4 pp.

Besser, J. F., J. W.

DeGrazio, and J. L. Guarino. 1968. Costs of wintering

starlings and red-winged blackbirds at feedlots. J.

Wildl. Manage. 32:179-180.

Besser, J. F., W. C.

Royall, Jr., and J. W. DeGrazio. 1967. Baiting starlings

with DRC-1339 at a cattle feedlot. J. Wildl. Manage.

31:45-51.

Blokpoel, H. 1976. Bird

hazards to aircraft. Clarke, Irwin & Co. Ltd., 236 pp.

Boudreau, C. W. 1975. How

to win the war with pest birds. Wildl. Tech., Hollister,

California. 174 pp.

Bystrak, D., C. S.

Robbins, S. R. Drennan, and R. Arbib, eds. 1974.

Wintering areas of bird species potentially hazardous to

aircraft. A special report jointly prepared by the Natl.

Audubon Soc. and the US Fish Wildl. Serv. Natl. Audubon

Soc., Inc., New York. 156 pp.

Constantin, B., and J.

Glahn. 1989. Controlling roosting starlings in

industrial facilities by baiting. Proc. Eastern Wildl.

Damage Control Conf. 4:47-52.

Crase, F. T., C. P. Stone,

R. W. DeHaven, and D. F. Mott. 1976. Bird damage to

grapes in the United States with emphasis on California.

US Fish Wildl. Serv., Special Sci. Rep. - Wildl. No.

197. Washington, DC. 18 pp.

DeCino, T. J., D. J.

Cunningham, and E. W. Schafer, Jr. 1966. Toxicity of

DRC-1339 to starlings. J. Wildl. Manage. 30:249-253.

DeHaven, R. W., and J. L.

Guarino. 1969. A nest-box trap for starlings.

Bird-Banding 40:49-50.

Dolbeer, R. A. 1984.

Blackbirds and starlings: population ecology and habits

related to airport environments. Proc. Wildl. Hazards to

Aircraft Conf. Training Workshop. Charleston, South

Carolina, US Dep. Trans. Rep. DOT/FAA/AAS/84-1:149-159.

Dolbeer, R. A. 1989.

Current status and potential of lethal means of reducing

bird damage in agriculture. Pages 474-483 in H. Ouellet,

ed., Acta XIX Congressus Int. Ornithol., Vol. I. Univ.

Ottawa Press, Ottawa, Canada.

Dolbeer, R. A., A. R.

Stickley, Jr., and P. P. Woronecki. 1978/1979. Starling,

Sturnus vulgaris, damage to sprouting wheat in Tennessee

and Kentucky, U.S.A. Prot. Ecol. 1:159-169.

Dolbeer, R. A., P. P.

Woronecki, R. L. Bruggers. 1986. Reflecting tapes repel

blackbirds from millet, sunflowers, and sweet corn.

Wildl. Soc. Bull. 14:418-425.

Dolbeer, R. A., P. P.

Woronecki, A. R. Stickley, Jr., and S. B. White. 1978.

Agricultural impacts of a winter population of

blackbirds and starlings. The Wilson Bull. 90:31.

Feare, C. J. 1980. The

economics of starling damage. Pages 39-55 in E. N.

Wright, I. R. Inglis, and C. J. Feare, eds. Bird

problems in agriculture, British Crop Prot. Council,

Croydon, UK. 210 pp.

Feare, C. J. 1984. The

starling. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. 315 pp.

Feare, C. J. 1989. The

changing fortunes of an agricultural bird pest: the

European starling. Agric. Zool. Rev. 3:317-342.

Feare, C. J., and K. P.

Swannack. 1978. Starling damage and its prevention at an

open-fronted calf yard. An. Prod. 26:259-265.

Fuller-Perrine, L. D., and

M. E. Tobin. 1993. A method for applying and removing

bird-exclusion netting in commercial vineyards. Wildl.

Soc. Bull. 21:47-51.

Glahn, J. F. 1982. Use of

starlicide to reduce starling damage at livestock

feeding operations. Proc. Great Plains Wildl. Damage

Control Workshop 5:273-277.

Glahn, J. F., and D. L.

Otis. 1986. Factors influencing blackbird and European

starling damage at livestock feeding operations. J.

Wildl. Manage. 50:15-19.

Glahn, J. F., and W.

Stone. 1984. Effects of starling excrement in the food

of cattle and pigs. An. Prod. 38:439-446.

Glahn, J. F., S. K.

Timbrook, and D. J. Twedt. 1987. Temporal use patterns

of wintering starlings at a southeastern livestock farm:

implications for damage control. Proc. Eastern Wildl.

Damage Control Conf. 3:194-203.

Glahn, J. F., D. J. Twedt,

and D. L. Otis. 1983. Estimating feed loss from starling

use of livestock feed troughs. Wildl. Soc. Bull.

ll:366-372.

Glahn, J. F., A. R.

Stickley, Jr., J. F. Heisterberg, and D. F. Mott. 1991.

Impact of roost control on local urban and agricultural

blackbird problems. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 19:511-522.

Good, H. B., and D. M.

Johnson. 1978. Nonlethal blackbird roost control. Pest

Control 46:14ff.

Gough, P. M., and J. W.

Beyer. 1982. Bird-vectored diseases. Proc. Great Plains

Wildl. Damage Control Workshop 5:260-272.

Heisterberg, J. F., A. R.

Stickley, Jr., K. M. Garner, and P. D. Foster, Jr. 1987.

Controlling blackbirds and starlings at winter roosts

using PA-14. Proc. Eastern Wildl. Damage Control Conf.

3:177-183.

Holler, N. R., and E. W.

Schafer, Jr. 1982. Potential secondary hazards of

avitrol baits to sharp-shinned hawks and American

kestrels. J. Wildl. Manage. 46:457-462.

Ingold, D. J. 1989.

Nesting phenology and competition for nest sites among

red-headed and red-bellied woodpeckers and European

starlings. Auk 106:209-217.

Johnson, R. J., P. K.

Cole, and W. W. Stroup. 1985. Starling response to three

auditory stimuli. J. Wildl. Manage. 49:620-625.

Johnson, R. J., and J. F.

Glahn. 1992. Starling management in agriculture. Coop.

Ext. Publ. NCR 451, Univ. Nebraska, Lincoln. 7pp.

Lefebvre, P. W., and J. L.

Seubert. 1970. Surfactants as blackbird stressing

agents. Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 4:156-161.

Lumsden, H. G. 1986.

Choice of nest boxes by tree swallows, Tachycineta

bicolor, house wrens, Troglodytes aedon, eastern

bluebirds, Sialia sialis, and European starlings,

Sturnus vulgaris. Can. Field-Nat. 100:343-349.

Lustick, S. 1976. Wetting

as a means of bird control. Proc. Bird Control Sem.

7:41-47.

Maccarone, A. D. 1987.

Effect of snow cover on starling activity and foraging

patterns. Wilson Bull. 99:94-97.

Mason, J. R., J. F. Glahn,

R. A. Dolbeer, and R. F. Reidinger. 1985. Field

evaluation of dimethyl anthranilate as a bird repellent

livestock feed additive. J. Wildl. Manage. 49:636-642.

Meanley, B., and W. C.

Royall, Jr. 1976. Nationwide estimates of blackbirds and

starlings. Proc. Bird Control Sem. 7:39-40.

McGilvrey, F. B., and F.

M. Uhler. 1971. A starling-deterrent wood duck nest box.

J. Wildl. Manage. 35:793-797.

Palmer, T. K. 1976. Pest

bird damage in cattle feedlots: the integrated systems

approach. Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 7:17-21.

Royall, W. C., Jr., T. C.

DeCino, and J. F. Besser. 1967. Reduction of a starling

population at a turkey farm. Poultry Sci. 46:1494-1495.

Schmidt, R. H., and R. J.

Johnson. 1984. Bird dispersal recordings: an overview.

Am. Soc. Testing Mat. STP 817, Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania 4:43-65 .

Shirota, Y., M. Sanada,

and S. Masaki. 1983. Eyespoted balloons as a device to

scare gray starlings. Appl. Ent. Zool. 18:545-549.

Stables, E. R., and N. D.

New. 1968. Birds and aircraft: the problems. Pages 3-16

in R. K. Murton and E. N. Wright, eds. Problems of birds

as pests. Acad. Press, London.

Stewart, P. A. 1978.

Foraging behavior and length of dispersal flights of

communally roosting starlings. Bird-Banding 49:113-115.

Stickley, A. R., Jr. 1979.

Extended use of starlicide in reducing bird damage in

southeastern feedlots. Proc. Bird Control Sem. 8:79-81.

Stickley, A. R., Jr., D.

J. Twedt, J. F. Heisterberg, D. F. Mott, and J. F. Glahn.

1986. Surfactant spray system for controlling blackbirds

and starlings in urban roosts. Wildl. Soc. Bull.

14:412-418.

Stickley, A. R., Jr., and

R. J. Weeks. 1985. Histoplasmosis and its impact on

blackbird-starling roost management. Proc. Eastern Wildl.

Damage Control Conf. 2:163-171.

Twedt, D. J., and J. F.

Glahn. 1982. Reducing starling depredations at livestock

feed operations through changes in management practices.

Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 10:159-163.

Weitzel, N. H. 1988.

Nest-site competition between the European starling and

native breeding birds in northwestern Nevada. Condor

90:515-517.

West, R. R. 1968.

Reduction of a winter starling population by baiting its

preroosting areas. J. Wildl. Manage. 32:637-640.

West, R. R., J. F. Besser,

and J. W. DeGrazio. 1967. Starling control in livestock

feeding areas. Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf., 3:89-93.

Will, T. J. 1983. BASH

Team new developments. Proc. Bird Control Sem. 9:7-10.

Wright, E. N. 1973.

Experiments to control starling damage at intensive

animal husbandry units. European Plant Prot. Organiz.

Bull. 9:85-89.

Wright, E. N. 1982. Bird

problems and their solutions in Britain. Proc. Vertebr.

Pest Conf. 10:186-189.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control E-109

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

01/08/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|