|

|

|

|

|

BIRDS: Blackbirds |

|

|

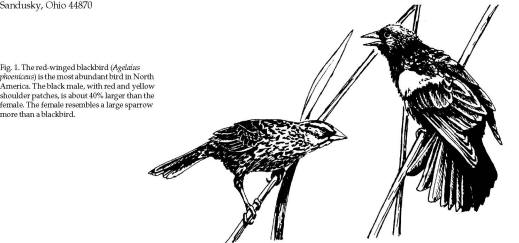

Fig. 1. The red-winged

blackbird

Introduction

The term blackbird loosely

refers to a diverse group of about 10 species of North

American birds that belong to the subfamily Icterinae.

In addition to blackbirds, this subfamily includes

orioles, meadowlarks, and bobolinks. The various species

of blackbirds have several traits in common. The males

are predominantly black or iridescent in color. All

blackbirds have an omnivorous diet consisting primarily

of grains, weed seeds, fruits, and insects. The relative

proportions of these food groups, however, vary

considerably among species. Outside of the nesting

season, blackbirds generally feed in flocks and roost at

night in congregations varying from a few birds to over

one million birds. These flocks and roosting

congregations are sometimes comprised of a single

species, but often several species mix together.

Sometimes they are joined by non-blackbird species,

notably European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) and

American robins (Turdus migratorius).

The species also have many

important differences in their nesting biology,

preferred foods, migration patterns, and their damage

and benefits to agriculture. Summarized below for each

of seven species of blackbirds is information on

identification, geographic range, preferred habitats,

feeding habits, general biology, and damage.

Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus)

Identification

The male, a little smaller

than a robin, is black with red and yellow shoulder

patches. The smaller female is brownish, resembling a

large sparrow (Fig. 1).

Range and Habitat

An abundant nester

throughout much of North America, the red-winged

blackbird nests in hayfields, marshes, and ditches.

Large flocks feed in fields and bottomlands. Redwings

winter in the southern United States.

Food Habits and General Biology

Insects are the dominant

food during the nesting season (May through July), with

the diet shifting predominantly to grain and weed seeds

in late summer through winter. Males and females often

forage in separated flocks, with females being more

insectivorous than males. Except during nesting season,

redwings congregate in large nighttime roosts in marshes

or woods containing up to several million birds. Annual

survival rate is only about 50% to 60%. This high

mortality rate is offset by a reproductive rate of 2 to

4 young fledged per female per year. Females have 3 to 5

eggs in their open-cup nests made of grasses and other

vegetation. Eggs hatch after 12 days of incubation; the

young grow rapidly and are ready to fledge about 10 days

later. Females will often renest if their initial nest

is destroyed.

Damage to Crops

Red-winged blackbirds can

cause considerable damage to ripening corn, sunflower,

sorghum, and oats in the milk and dough stages, and to

sprouting and ripening rice. These birds provide some

benefits by feeding on harmful insects, such as rootworm

beetles and corn earworms, and on weed seeds, such as

Johnson grass.

Common

Grackle (Quiscalus quiscula) Common

Grackle (Quiscalus quiscula)

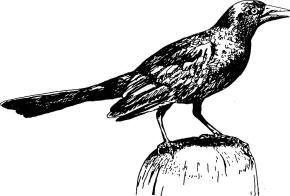

Fig. 2. The common grackle

(Quiscalus quiscula) is an iridescent blackbird, larger

than a robin, with a long, keel-shaped tail.

Identification

An iridescent blackbird

larger than a robin, the common grackle has a long

keel-shaped tail. The male, slightly larger than the

female, has more iridescence on the head and throat

(Fig. 2).

Range and Habitat

A common nester throughout

North America east of the Rockies, the common grackle

nests in shelterbelts, farmyards, marshes, and towns.

Flocks feed in fields, lawns, woodlots, and bottomlands.

These birds winter in the southern United States, often

in association with redwings, cowbirds, and starlings.

Food Habits and General

Biology

The common grackle’s diet

is somewhat similar to that of the redwing, but the

grackle is more predatory. Its diet occasionally

includes small fish, field mice, songbird nestlings, and

eggs. Grackles have a larger, stronger bill than

redwings, allowing them to feed on acorns and other tree

fruits in winter. Grackles often roost with redwings,

but are more partial to roosting sites in upland

deciduous or pine trees. Reproductive and survival rates

are similar to redwings.

Damage to Crops

Damage is similar to that

of redwings; however, grackles will feed on mature field

corn in the dent stage, removing entire kernels from the

cob. Also, grackles will pull up sprouting corn.

Great-tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus)

Identification This

species is similar to the common grackle but with a much

larger tail. The male is slightly smaller than a crow;

the female is smaller and browner than the male.

Range and Habitat

An abundant year-round resident in coastal and

southern Texas, the great-tailed grackle nests in

colonies in shrubs or trees, sometimes in association

with herons and egrets. The flocks feed around farms,

pastures, and parks.

Food Habits and General

Biology

The diet is omnivorous: insects, aquatic organisms,

eggs from nesting birds, fruits, and grains.

Reproductive and survival rates are similar to those of

redwings.

Damage to Crops

These birds damage all

types of fruits and melons, although the loss is

generally minor. In recent years, however, their damage

to citrus crops in localized areas of the lower Rio

Grande Valley of Texas has been substantial. Great-tails

peck the citrus fruit skin, creating blemishes or holes.

Brown-headed

Cowbird (Molothrus ater) Brown-headed

Cowbird (Molothrus ater)

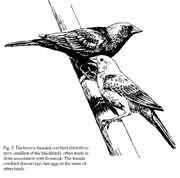

Identification

The cowbird is the

smallest blackbird. The male is black with a brown head

and the female is gray. Both sexes have sparrowlike

bills (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. The brown-headed

cowbird (Molothrus ater), smallest of the blackbirds,

often feeds in close association with livestock. The

female cowbird (lower) lays her eggs in the nests of

other birds.

Range and Habitat

Cowbirds occur in spring

and summer throughout much of North America. Flocks feed

in pastures and feedlots, and are often associated with

livestock. Cowbirds winter in the central to southern

United States, often roosting with redwings, grackles,

and starlings.

Food Habits and General

Biology

The diet of cowbirds

consists predominantly of weed seeds and grains, and

less than 25% insects. Cowbirds do not build nests or

incubate eggs; the female lays her eggs in nests of

other songbirds, the only North American songbird to do

so. Females deposit 1 or sometimes 2 eggs per host nest,

laying up to 25 or more eggs per nesting season.

Damage to Crops

This species can cause

damage to ripening sorghum, sunflower, and millet.

Cowbirds consume some livestock feed, but often glean

waste grain and seed from dung. Overall damage is

usually minor.

Yellow-headed Blackbird (Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus)

Identification

A robin-sized bird, the

male has a striking appearance with his black body,

conspicuous yellow head and breast, and a white wing

patch in flight. The female is smaller and browner, with

a yellowish throat and breast.

Range and Habitat

Yellowheads are locally

abundant nesters in deep-water marshes of the northern

Great Plains and western North America. They feed in

agricultural fields, meadows, and pastures during late

summer and fall, sometimes in association with redwings

or other blackbirds. They winter farther south than

other blackbirds, primarily in Mexico.

Food Habits and General

Biology

The diet is similar to

that of redwings; yellowheads eat primarily insects

during the nesting season and grains and weed seeds at

other times. An early An early migrant, the yellowhead

leaves the northern plains by September. Survival and

reproductive rates are similar to those of redwings.

Damage to Crops

Yellowheads cause

localized but generally minor damage to ripening corn,

sunflower, and oats, often in association with redwings.

They often leave the northern prairie regions by the

time corn and sunflower are ripening in autumn.

Brewer’s

Blackbird (Euphagus cyanocephalus)

Identification

A robin-sized bird, the

male is all black with whitish eyes; the female is

brownish gray with dark eyes.

Range and Habitat

A familiar bird in the

northern Great Plains and western North America, the

Brewer’s blackbird nests in a diversity of habitats. It

prefers pastures, lawns, and agricultural lands for

feeding. It is a winter migrant in the central and

southern Plains states, sometimes roosting with other

blackbird species.

Food Habits and General

Biology

The diet is about

two-thirds grain and weed seeds, and one-third insects

and other animal matter. They feed in flocks on waste

grain and weed seeds and nest in colonies. Reproductive

and survival rates are similar to those of redwings.

Damage to Crops

Brewer’s blackbirds cause

generally minor damage to oats, fruit crops, and

livestock feed and consume large numbers of noxious

insects during the summer months.

Rusty Blackbird (Euphagus carolinus)

Identification

Similar to Brewer’s

blackbird, its fall and winter plumage has a rusty

coloration.

Range and Habitat

Rusty blackbirds nest in

northern swamps and muskegs (bogs) throughout Canada,

Alaska, and northern New England. They migrate in winter

to the southern United States from the Atlantic coast to

east Texas.

Food Habits and General

Biology

The diet of rusty

blackbirds is more insectivorous than that of other

blackbirds. Over 50% of their food is animal matter.

Grain (gleaned from harvested fields in fall and

winter), weed seeds, and tree fruits are also eaten. In

winter, rusty blackbirds prefer swampy areas and river

bottoms. They often roost with other blackbird species.

Damage to Crops

This species does little

damage to crops.

Damage Identification and Assessment

Blackbird

damage to agricultural crops is often readily

discernable because of the conspicuousness of the flocks

of birds and the visible signs of the damage. However,

correct identification of the species of birds in the

agricultural field is important, along with evidence

that the birds are actually feeding on the crop. For

example, starlings superficially resemble blackbirds and

sometimes feed in cornfields, yet they usually feed on

concentrations of insects such as armyworms, doing

little damage to corn. Also, red-winged blackbirds will

often be attracted to agricultural fields, such as corn,

initially to feed on rootworm beetles and other insect

pests. They will not damage the crop itself until the

grain has reached the milk stage. Blackbirds often

forage in newly planted grain fields such as winter

wheat, feeding on previous crop residue, weed seeds, and

insects without bothering the sprouting grain. Blackbird

damage to agricultural crops is often readily

discernable because of the conspicuousness of the flocks

of birds and the visible signs of the damage. However,

correct identification of the species of birds in the

agricultural field is important, along with evidence

that the birds are actually feeding on the crop. For

example, starlings superficially resemble blackbirds and

sometimes feed in cornfields, yet they usually feed on

concentrations of insects such as armyworms, doing

little damage to corn. Also, red-winged blackbirds will

often be attracted to agricultural fields, such as corn,

initially to feed on rootworm beetles and other insect

pests. They will not damage the crop itself until the

grain has reached the milk stage. Blackbirds often

forage in newly planted grain fields such as winter

wheat, feeding on previous crop residue, weed seeds, and

insects without bothering the sprouting grain.

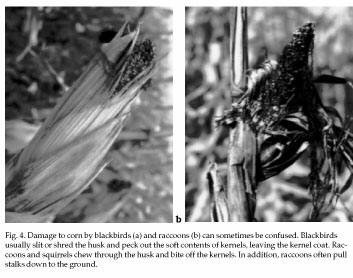

Blackbird damage is also

sometimes confused with other forms of loss. Raccoon and

squirrel damage to corn can be mistaken for blackbird

damage (Fig. 4). Also, seed shatter in sunflower caused

by wind may resemble bird damage; however, the

difference can usually be detected by examining heads

for the presence or absence of bird droppings and by

looking on the ground for hulls or whole seeds. Careful

observation of the birds in the field and a little

detective work will usually result in the correct

identification of damage.

To estimate accurately the

amount of blackbird damage in an agricultural field,

examine at least 10 locations widely spaced throughout

the field. For example, if a field has 100 rows and is

1,000 feet (300 m) long, walk staggered distances of 100

feet (30 m) along every 10th row (for example, 0 to 100

feet [0 to 30 m] in row 10, 101 to 200 feet [31 to 60 m]

in row 20, and so on). In each of the 100-foot (30-m)

lengths, randomly select 10 plants and visually estimate

the damage on the head or ear of each plant to the

nearest 1% (for instance, 2% destroyed, 20% destroyed).

For corn, six kernels usually represent about 1% of the

corn on an ear; for sunflower, it may be easiest to

visually divide the head into four quarters and then

estimate the percentage of seeds missing. When finished,

simply determine the average damage for the 100 plants

examined. This will give an approximation of the percent

loss to the field. Multiplying the percent loss by

expected yield can give a rough estimate of yield loss.

In small grains, such as rice, estimates of loss are

more difficult to obtain. One possibility is to simply

compare the yields from plots in damaged and undamaged

sections of a field.

Legal Status

Blackbirds are native

migratory birds, and thus come under the jurisdiction of

the Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act, a formal treaty

with Canada and Mexico. Blackbirds are given federal

protection in the United States. They may be killed only

when found “committing or about to commit depredations

upon ornamental or shade trees, agricultural crops,

livestock, or wildlife, or when concentrated in such

numbers and manner as to constitute a health hazard or

other nuisance,” as stated in federal laws regarding

migratory birds (50 CFR 21). Some states have additional

restrictions on the killing of blackbirds.

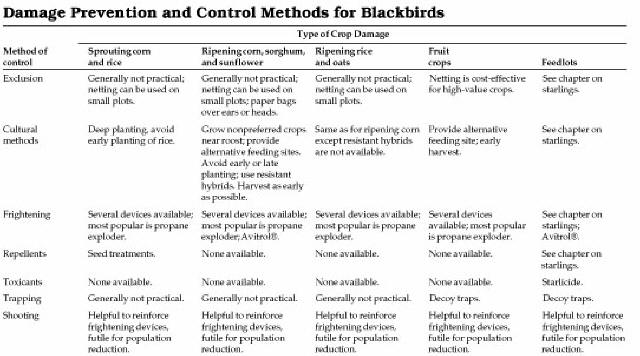

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Exclusion of blackbirds

from agricultural crops is practical only for small

gardens, experimental plots, and high-value fruit crops.

Use lightweight netting to cover trees, bushes, or small

plots. Protect individual ears of sweet corn in garden

plots by placing paper bags over them after the silk has

turned brown.

Cultural Methods and Habitat Modification

Most economically severe

blackbird damage to agricultural crops occurs in fields

within 5 miles (8 km) of roosts. Thus, one strategy is

to plant nonattractive crops—such as soybeans, wheat,

potatoes, or hay—in fields within a few miles of a

roost. If crops vulnerable to damage, such as corn or

sunflower, are planted near a roost, alternative feeding

sites should be made available to reduce the feeding

pressure on these cash crops. Delaying the plowing or

tilling of previously harvested cropland near roosts to

provide alternative feeding sites is one strategy to

reduce damage to maturing crops. Also, fields near

roosts should not be planted unusually early or late so

that they mature in isolation from other fields in the

area. In general, as alternative feeding sites decline,

maturing grain or sunflower fields become more

attractive to blackbirds, and keeping them out becomes

more difficult.

Experimental programs are

under way in sunflower production areas of the northern

plains to thin out dense stands of cattails in marshes

where large numbers of blackbirds roost. A registered

herbicide (Rodeo®) is applied in swaths to about 70% of

the marsh. Thinning the cattail stands decreases

blackbird roosts in the marsh and increases use by

waterfowl for nesting and other activities.

Damage to sprouting rice

fields planted near blackbird roosts in Louisiana and

Texas can be substantially reduced by delaying planting

until April. By this time, the large flocks of migrant

blackbirds will have left for their northern nesting

areas.

The timing of harvest can

be very important in reducing damage to fields from

flocks of blackbirds. For example, redwings inflict most

damage to sweet corn at the time of fresh-market

harvest, when the corn enters the milk stage. Timely

harvest of sweet corn can substantially reduce damage.

Although field corn generally becomes unattractive to

birds when the kernels mature, sunflower, sorghum, and

rice continue to be attractive after they mature and

thus should be harvested as soon as possible.

Hybrids of corn with long

husk extension and thick husks are more resistant to

damage than other hybrids. Sorghum that contains a high

tannin content is also less preferred than low-tannin

varieties. For sunflower, birds prefer oil seed

cultivars over the confectionery cultivars. Using

sunflower cultivars with heads that turn downward as

they mature and seeds with thick hulls should also help

reduce feeding by blackbirds.

Frightening

The use of frightening devices can be quite

effective in protecting crops from flocks of blackbirds.

Their use also requires hard work and long hours for the

farmer, who needs to be persistent and innovative to

keep one step ahead of the birds. Devices need to be

employed especially in the early morning and in late

afternoon when the birds are most actively feeding.

Crops such as sweet corn, which are vulnerable to

blackbirds for only a few days before harvest, may not

be too difficult to protect; however, the task becomes

more formidable for crops such as sunflower and sorghum,

which may be vulnerable for up to six weeks. Propane

exploders (some with timers that automatically turn them

on and off each day) are the most popular frightening

devices. In general, use at least one exploder for every

10 acres (4 ha) of crop to be protected. Elevate

exploders on a barrel, stand, or truck bed to “shoot”

over the crop, and move them around the field every few

days. In addition, reinforce this technique occasionally

with other scare devices. By shooting a .22 caliber

rifle just over the top of a crop, a person on a stand

or truck bed can frighten birds from fields of 40 acres

(16 ha) or more. Obviously, care must be taken when

shooting in this manner, and the use of limited range

cartridges is recommended. Also effective are shell

crackers, 12-gauge shotgun shells containing fire

cracker projectiles that explode after traveling up to

150 yards (135 m). Shooting birds with a shotgun, using

standard bird shot, often can kill a few birds and

reinforce other scare devices. This technique, however,

usually is not as effective in moving birds as the other

devices that have greater range. Thus, a shotgun patrol

should not be used as the sole means of frightening

birds.

Fig. 5. Mylar reflecting

tape strung above the vegetation can reduce blackbird

feeding activity in agricultural fields.

A variety of other

bird-frightening devices, including electronic noise

systems, helium-filled balloons tethered in fields,

radio-controlled model planes, reflecting tapes made of

mylar (Fig. 5), tape-recorded distress calls for birds,

and various types of scarecrows, are also occasionally

used to rid fields of blackbirds. The effectiveness of

these devices is highly variable, depending on the

persistence of the operator, the skill used in employing

a device, the attractiveness of the crop, the number of

birds, and the availability of alternate feeding sites.

As mentioned with regard to propane exploders, birds

tend to adjust or adapt to frightening devices. It is

usually best to use two or more devices than to rely on

a single device.

Avitrol® is a registered

chemical frightening agent for blackbirds in corn and

sunflower fields. One out of every 100 particles of

cracked-corn bait is treated with the chemical,

4-amino-pyridine. The bait is applied to fields in

swaths, often by airplane, at the rate of 3 pounds per

acre (3.3 kg/ha) to one-third of the field. The

ingestion of one or more treated particles by a

blackbird induces erratic flight, distress calls, and

usually death. This behavior often causes the remaining

birds in the flock to leave the field.

Careful consideration must

be given to the timing of initial and repeat baitings.

Begin baitings when birds first initiate damage, and

repeat as necessary, typically at 5- to 7-day intervals.

Dense weed populations that hide bait, ground insects

such as crickets that eat bait, and excessive rainfall

can contribute to making the product ineffective.

Repellents

No bird repellents are currently registered for

maturing grain, sunflower, or fruit crops. Several

seed-treatment repellents such as Ro-pel® (active

ingredient is benzyl diethyl ammonium saccharide) and

Sevana Bird Repellent (ground garlic and pepper) have

been registered to reduce bird damage to freshly planted

and sprouting corn and other crops. However, the

registration status of these products changes

continually; thus, check with county extension agents or

USDA-APHIS-ADC biologists for products currently

registered.

Toxicants

Starlicide is a registered toxicant for blackbirds

and starlings in feedlot situations. The active

ingredient, 3-chloro-p-toluidine hydrochloride, is

incorporated into pelletized bait at a concentration of

0.1% and sold commercially under the trade name

Starlicide Complete®. Starlicide Technical® (98% active

ingredient), which can be custom-mixed with livestock

feed or other bait material, is also available through

the USDA-APHIS-ADC Program. Starlicide Technical® can be

used only by or under supervision of ADC employees.

Starlicide is a

slow-acting toxicant; birds usually die 1 to 3 days

after feeding. Baiting programs are most successful in

winter, especially with snow cover present, when

alternate foods are scarce. A successful program

generally requires a period of prebaiting with nontoxic

bait to accustom the target blackbirds and starlings to

feed at specific bait sites inaccessible to livestock in

the feedlot. Monitoring to ensure that nontarget birds

such as doves, song birds, and barnyard fowl do not feed

at bait sites is essential. See the chapter Starlings

for more details on the use of Starlicide.

Trapping

Certain species of blackbirds, particularly

redwings, brown-headed cowbirds, and common grackles,

often can be readily trapped in decoy traps. Consult a

state wildlife official, such as a conservation officer

or game warden, before putting a decoy trap into

operation. A decoy trap is a large (for instance, 20 x

20 x 6 feet [6 x 6 x 1.8 m]) poultry wire or net

enclosure containing 10 to 20 decoy birds, food, and

water (Fig. 6). Birds enter the trap through an opening

(often 2 x 4 feet [0.6 x 1.2 m]) in the top of the cage

that is covered with 2 x 4-inch (5 x 10-cm) welded wire.

The blackbirds can fold their wings and readily drop

through the openings to the food (generally cracked

corn, millet, or sunflower seeds) below. A small (for

example, 2 x 2 x 3 feet [0.6 x 0.6 x 0.9 m]) gathering

cage with a sliding door attached to an opening at an

upper corner of the trap can be used to collect trapped

birds. A corralling baffle running about two-thirds the

length of the trap can aid in driving the birds into the

gathering cage.

Fig. 6. A typical

blackbird and starling decoy trap showing elevated feed

platform in center of trap and gathering cage on the far

right. Birds enter the trap through a 2 x 4-foot (0.6 x

1.2-m) opening covered with 2 x 4-inch (5 x 10-cm)

welded wire located directly above the feed platform.

A decoy trap often catches

10 to 50 blackbirds and starlings per day and

occasionally up to 300 when located near a large roost.

Obviously, the decoy trap is of questionable value in

trying to reduce large roosting populations and damage

to the surrounding agricultural fields. These traps,

however, can be used to temporarily reduce local

populations of blackbirds in special situations. For

example, decoy traps have been used successfully in a

six-county area of Michigan since the 1970s to reduce

cowbird populations during the nesting season. This

control was initiated to increase the nesting success of

the Kirtland’s warbler (Dendroica kirtlandii), an

endangered species whose nests are often used by

cowbirds for laying their own eggs.

Each year about 3,500

cowbirds have been captured by decoy traps in this area

of Michigan. Decoy traps might also be successful in

reducing localized populations around feedlots or fruit

crops.

Any nontarget songbirds

accidentally captured in a decoy trap should be released

immediately. Blackbirds to be disposed of should be

killed humanely. They can be transferred from the

gathering cage to a cardboard box or canvas-covered cage

and asphyxiated with carbon dioxide gas. All dead birds

should be examined for bands, and any bands found should

be reported. One option for disposal that should not be

overlooked is culinary. Blackbirds, being primarily

grain eaters, make good food for humans! Recipes for

quail or dove also work well for blackbirds.

Shooting

As discussed under Frightening, shooting to kill

with a shotgun is most effective when used occasionally

to supplement or reinforce other scare devices. By

itself, shooting with a shotgun is not cost-effective in

frightening blackbirds from large agricultural fields,

and it is totally ineffective as a means of reducing

populations. Any killed birds should be examined for

bands.

Economics of Damage and Control

Superficial surveys of

agricultural fields often overestimate blackbird damage

and thus exaggerate the overall severity of the economic

threat for one of four reasons: (1) the conspicuousness

of blackbird flocks tends to heighten the awareness of

bird damage compared with other more subtle forms of

loss caused by weeds, insects, other pests, and

harvesting; (2) the eye naturally seeks out the

conspicuously bird-damaged plants; (3) bird damage is

often most severe along field edges where an observer is

most likely to check; and (4) raccoon, other mammal, or

wind damage is sometimes mistaken for bird damage (see

the section Damage Identification and Assessment). This

is not to downgrade the problem of blackbird damage in

agriculture; damage can be economically severe on

occasion and quite frustrating to the farmer when relief

is not readily available. It is important, however, to

obtain objective estimates of damage levels likely to

occur, for only then can intelligent decisions be made

regarding the amount of money and effort to be invested

on control. The final decision on control measures must

take into account the value of the crop, cost of

control, and the degree of effectiveness of the control

measure in relation to the probable levels of damage.

Studies during the past

two decades concerning blackbird damage to various crops

such as corn and sunflower indicate that on statewide or

regional bases, overall mean damage is low, generally

less than 1% of the crop. If all farmers received less

than 1% damage, there would be little concern; however,

the damage is not equally distributed. While most

farmers escape economically serious damage, a few

farmers receive serious damage. For example, in North

Dakota, South Dakota, and Minnesota in 1979 and 1980,

overall loss of sunflower to blackbirds was estimated to

be only 1.2% of the crop. Yet, 2% of the fields received

more than 10% loss. Only in these relatively few fields

that sustain high levels of damage can control measures

generally be cost-effective.

While accurate prediction

of damage is often impossible to obtain, knowledge of

the location of a field in relation to traditional

roosting sites often provides the basis for a sound

estimate of potential damage. For example, studies of

blackbird damage to ripening corn in Ohio have revealed

that almost all losses exceeding 5% of the crop have

occurred in fields within 5 miles (8 km) of marsh

roosts.

Objective estimates of

damage levels in previous years for the same or nearby

fields are another means of predicting future damage

levels, because bird damage is fairly consistent from

year to year within a locality. This information also

provides a good baseline for evaluating the

effectiveness of management strategies. Of course, it is

important that estimates be objective and apply to the

entire field.

Acknowledgments

Figures 1 through 3 by

Emily Oseas Routman.

Figures 4, 5, and 6 by the

author.

For Additional Information

Bent, A. C. 1965. Life

histories of North American blackbirds, orioles,

tanagers, and allies. Dover Publ., Inc., New York. 549

pp. and 37 plates.

Besser,

J. F. 1978. Birds and sunflowers. Pages 263-278 in J. F.

Carter, ed. Sunflower science and technology. Amer. Soc.

Agron., Crop Sci. of Amer., Soil Sci. Soc. of Amer.,

Inc., Madison, Wisconsin.

Dolbeer,

R. A. 1981. Cost-benefit determination of blackbird

damage control for cornfields. Wildl. Soc. Bull.

9:43-50.

Dolbeer,

R. A. 1990. Ornithology and integrated pest management:

the red-winged blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus). Ibis

132:309-322.

Robbins, C. S., B. Bruun,

and H. S. Zim. 1983. Birds of North America: a guide to

field identification. Golden Press, New York. 360 pp.

White, S. B., R. A.

Dolbeer, and T. A. Bookhout. 1985. Ecology,

bioenergetics, and agricultural impact of a

winter-roosting population of blackbirds and starlings.

Wildl. Monogr. 93. 42 pp.

Wilson, E. A., E. A.

LeBoeuf, K. M. Weaver, and

D. J. LeBlanc. 1989.

Delayed seeding for reducing blackbird damage to

sprouting rice in southwestern Louisiana. Wildl. Soc.

Bull. 17:165-171.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom; Robert

M. Timm; Gary E. Larson

01/08/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|