|

|

|

|

|

BIRDS: Bird Dispersal Techniques |

|

|

Introduction

Birds, especially

migratory birds, provide enjoyment and recreation for

many and greatly enhance the quality of our lives. These

colorful components of natural ecosystems are often

studied, viewed, photographed, hunted, and otherwise

enjoyed.

Unfortunately, bird

activities sometimes conflict with human interests.

Birds may depredate agricultural crops, create health

hazards, and compete for limited resources with other

more favorable wildlife species. The management of bird

populations or the manipulation of bird habitats to

minimize such conflicts is an important aspect of

wildlife management. Problems associated with large

concentrations of birds can often be reduced through

techniques of dispersal or relocation of such

concentrations.

Dispersal Techniques

Two general approaches to

dispersing bird concentrations will be discussed in this

chapter: (1) environmental or habitat modifications that

either exclude or repel birds or make an area less

attractive, and (2) the use of frightening devices. The

following chapters in this publication also discuss bird

dispersal techniques in detail: Bird Damage at

Aquaculture Facilities, Birds at Airports, Waterfowl,

and Blackbirds.

Habitat Modifications

Habitat modifications

include a myriad of activities that can make

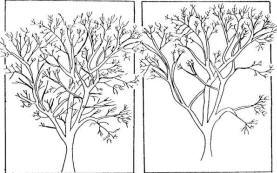

Fig.

1. Before and after pruning trees to reduce

attractiveness as a bird roost. Fig.

1. Before and after pruning trees to reduce

attractiveness as a bird roost.

habitats less attractive

to birds. Thinning or pruning of vegetation to remove

protective cover can discourage birds from roosting

(Fig. 1). Most deciduous trees can withstand removal of

up to one-third of their limbs and leaf surface without

causing problems. Adverse effects are minimized during

the dormant season. Thinning often enhances commercial

timber production. Dramatic changes are not always

necessary, however. Sometimes subtle changes are

effective in making an area unattractive to birds and

causing bird concentrations to disperse or relocate to a

place where they will not cause problems. Bird dispersal

resulting from habitat modifications usually produces a

more lasting effect than other methods and is less

expensive in the long run.

Frightening Devices

The use of frightening

devices can be extremely effective in manipulating bird

concentrations. The keys to a successful operation are

timing, persistence, organization, and diversity. Useful

frightening devices include broadcasted alarm and

distress calls, pyrotechnics, exploders, and other

miscellaneous auditory and visual frightening devices

(see Supplies and Materials for information on

commercial products). No single technique can be

depended upon to solve the problem. Numerous techniques

must be integrated into a frightening program.

Electronic Devices.

Recorded alarm and distress calls of birds are very

effective in frightening many species of birds and are

useful in both rural and

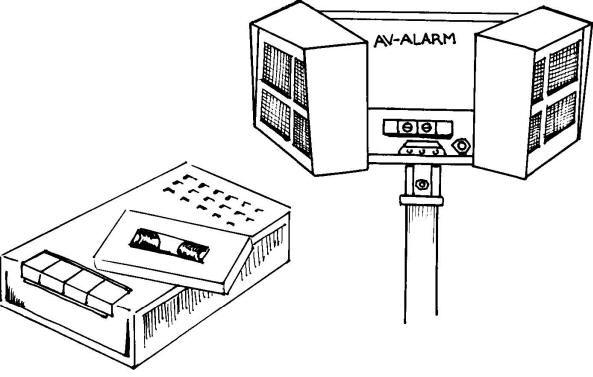

Fig.

2. (a) Recorded bird alarm or distress calls can be

effective in frightening birds. Fig.

2. (a) Recorded bird alarm or distress calls can be

effective in frightening birds.

urban situations. The

calls are amplified and broadcasted (Fig. 2a).

Periodically move the broadcast units to enhance the

effectiveness of such calls. If stationary units must be

used, increase the volume to achieve greater responses.

Electronically produced sounds such as Bird-X , AV-ALARM

, or other sound generators (Fig. 2b), will frighten

birds, but are usually not as effective as amplified

recorded bird calls. This should not discourage their

use, however. The greater the variety and disruptiveness

of sounds, the more effective the method will be as a

repellent.

Pyrotechnics. Pyrotechnic

devices have long been employed in bird frightening

programs. Safe and cautious use of these devices should

be emphasized. The 12-gauge exploding shells (shell

crackers) are very effective (Fig. 3). They are useful

in a variety of situations because of their long range.

Fire shell crackers from the hip (to protect eyes) from

single-barrel, open-bore shotguns and check the barrel

after each round to be sure no obstruction remains. Some

types of 12-gauge exploding shells are corrosive,

requiring that the gun be cleaned after each use to

prevent rusting. Though more expensive, smokeless powder

shells will reduce maintenance.

Pyrotechnics should be

stored, transported, and used in conformance with

(b) Electronically

produced sounds also will frighten birds away from an

area.

laws, regulations, and

ordinances.

Several devices that are

fired from 15mm or 17-mm pistols are used to frighten

birds. For the most part, they cover a shorter range

than the 12gauge devices. They are known by many brand

names but are usually called screamers if they explode,

and if they do not. Both types should be used

together for optimal results. Noises up in the air near

the birds are much more effective than those on the

ground. The use of a shotgun with live ammunition is one

of the most available but least effective means of

frightening birds. Shotgun fire, however, may increase

the effectiveness of other frightening devices. Live

shotgun shells should not be included in a frightening

program unless there is certainty that no birds will be

crippled and later serve as live decoys. Also, live

ammunition creates safety problems in urban areas and is

often illegal. Rifles (.22 caliber) fired from elevated

locations are effective where they can be used safely.

Rope firecrackers are an

inexpensive way to create unattended sound (Fig. 4). The

fuses of large firecrackers (known as fuse-rope salutes

or agricultural explosive devices) are inserted through

5/16- or 3/8-inch (8- or 9.5-mm) cotton rope. As the

rope burns, the fuses are ignited. The time between

explosions can be regulated by the spacing of the

firecrackers in the rope. The ability to vary the

intervals is an asset since birds can become accustomed

to explosions at regular intervals. Burning speed of the

rope can be increased by soaking it overnight in a

saltpeter solution of 3 ounces per quart (85 g/l) of

water and allowing it to dry. Since the burning speed of

the rope is also affected by humidity and wind speed, it

is wise to time the burning of a test section of the

rope beforehand. Because of the fire hazard associated

with this device, it is a good idea to suspend it over a

barrel, or make other fire prevention provisions.

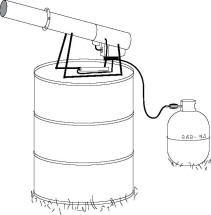

Exploders.

Automatic LP gas exploders are another source of

unattended sound (Fig. 5). It is important to elevate

these devices above the level of the surrounding

vegetation. Mobility is an asset and will increase their

effectiveness, as will changing the interval between

explosions.

Other Frightening

Materials.

Other frightening devices

include chemicals such as Avitrol® and a great variety

of whirling novelties and flashing lights, as well as

innovative techniques such as smoke, water sprays,

devices to shake roosting vegetation, tethered balloons,

hawk silhouettes, and others. While all of these, even

the traditionally used scarecrow (human effigies), can

be useful in specific situations, they are only

supplementary to a basic, well-organized bird

frightening program. Combining different devices such as

human effigies (visual) and exploders (auditory) produce

better results than either device used separately.

Bird

Dispersal Operations Again, the keys to successful bird

dispersal are timing, persistence, organization, and

diversity. The timing of a frightening program is

critical. Birds are much more apt to leave a roost site

that they have occupied for a brief period of time than

one that they have used for many nights. Prompt action

greatly reduces the time and effort required to

successfully relocate the birds. As restlessness

associated with migration increases, birds will become

more responsive to frightening devices and less effort

is required to move them. When migration is imminent,

the birds natural instincts will augment dispersal

activities. Bird

Dispersal Operations Again, the keys to successful bird

dispersal are timing, persistence, organization, and

diversity. The timing of a frightening program is

critical. Birds are much more apt to leave a roost site

that they have occupied for a brief period of time than

one that they have used for many nights. Prompt action

greatly reduces the time and effort required to

successfully relocate the birds. As restlessness

associated with migration increases, birds will become

more responsive to frightening devices and less effort

is required to move them. When migration is imminent,

the birds natural instincts will augment dispersal

activities.

Fig. 3. Shell crackers are

fired from a 12-gauge shotgun. They produce an aerial

explosion and can be useful in frightening birds out of

fields or away from roosts.

Fig.

5. Automatic LP gas exploders make loud sounds that

frighten birds. Controlled by a timer, they can be left

unattended. Fig.

5. Automatic LP gas exploders make loud sounds that

frighten birds. Controlled by a timer, they can be left

unattended.

Fig. 4. Rope firecrackers

are relatively inexpensive tools that are useful in

frightening birds.

Whether dealing with rural

or urban concentrations, someone should be in charge of

the entire operation and carefully organize all

dispersal activities. The more diverse the techniques

and mobility of the operation, the more effective it

will be. Once initiated, the program must be continued

each day until success is achieved. The recommended

procedure for dealing with an urban blackbird/starling

roost is given below. Many of these principles apply to

other bird problems as well.

Urban

Roost Relocation Procedure

Willing and

effective cooperation among numerous agencies,

organizations, and individuals is necessary to undertake

a successful bird frightening program in an urban area.

Different levels of government have different legal

responsibilities for this work. The best approach is a

cooperative effort with the most knowledgeable and

interested individual coordinating the program.

Public relations efforts

should precede an urban bird-frightening effort.

Federal, state, and/or local officials should explain to

the public the reasons for attempting to relocate the

birds. Announcements should continue during the

operation and a final report should be made through mass

media. These public relations efforts will facilitate

public understanding and support of the program. They

will also provide an opportunity to solicit citizen

involvement. This help will be needed when the birds

scatter all over town after one or two nights of

frightening. Traffic control in the vicinity of the

roost is essential. Consequently, police involvement and

that of other city officials is necessary.

The public should be

informed that the birds may move to a site that is less

suitable than the one they left and that, if disturbed

in the new roost site, they are likely to return to the

original site. Sometimes it is wise to provide

protection for a new, acceptable roost site once it has

been selected by the birds. One can predict with some

certainty that blackbirds and starlings will move to one

of their primary staging areas if that area contains

sufficient roosting habitat. Fortunately, if the birds

occupy roost sites where they still create problems, a

continuation of the frightening program can more easily

cause them to move to yet another site. With each

successive move, the birds become more and more

responsive to the frightening devices. Habituation is

uncommon in properly conducted programs, especially if

sufficient diversity of techniques and mobility of

equipment is maintained.

Birds are much easier to

frighten while they are flying. Once they have perched,

a measure of security is provided by the protective

vegetation and they become more difficult to frighten.

Dispersal activities should end when birds stop moving

after sunset. A continuation of frightening will only

condition birds to the sounds and reduce responses in

the future. With black-bird/starling roosts, all

equipment and personnel should be prepared to begin

frightening at least 1 1/2 hours before dark. The

frightening program should commence as soon as the first

birds are viewed. Early morning frightening is also

effective. This requires only about 1/2 hour and should

begin when the first bird movement occurs within the

roost, which may be prior to daylight. This movement

precedes normal roost exodus time by about 1/2 hour.

On the first night of a

bird-roost frightening program, routes for mobile units

should be planned and shooters of exploding shells

should be placed so as to build a wall of sound around

the roost site and saturate the roost with sound.

Shooters should be cautioned to ration their ammunition

so that they do not run out before dark. The response of

the birds is predictable. As flight lines attempt to

enter the roost site in late afternoon, they will be

repelled by the frightening effort. A wall of birds

about 1/4 mile (0.4 km) from the roost site will mill

and circle almost until dark. At that time, virtually

all of the birds will come into the roost site, no

matter what frightening methods are employed.

The immediate response of

onlookers is also predictable. Pulling for the underdog

(or in this case the underbirds), they will cheer for

the birds and assume that the program has been

unsuccessful. This is wholesome community recreation.

When the birds are finally gone, however, these same

onlookers will be convinced that frightening devices

are, in fact, effective in moving birds.

By the second and third

nights of the frightening program, flexibility will be

necessary in adapting dispersal techniques to the birds

behavior. As larger numbers of birds are repelled from

the original roost site, they will attempt to establish

numerous temporary roosts. Mobile units armed with

pyrotechnics and broadcast alarm and distress calls

should be prepared to move to these areas, disturb the

birds, and send them out of town. Frightening efforts by

residents should be encouraged through mass media.

Efforts must continue each morning and evening in spite

of weather conditions. Complete success is usually

achieved by the fourth or fifth night.

A bird-frightening program

can be used to deal with an immediate bird problem, but

it can also be an educational tool that prepares

individuals or municipalities to deal with future

problems in an effective manner. Those interested in

resolving the problem should bear part of the financial

burden of the bird-frightening program. This requirement

will immediately eliminate imagined bird problems. When

a city or individual is willing to pay a part of the

bill for a bird-frightening operation, it is obvious

that a genuine problem exists.

Summary

Large concentrations of

birds sometimes conflict with human interests. Birds can

be dispersed by means of habitat manipulation or various

auditory and visual frightening devices. The keys to

effective bird dispersal programs are timing,

persistence, organization, and diversity. The proper use

of frightening devices can effectively deal with

potential health and/or safety hazards, depredation, and

other nuisances caused by birds.

Acknowledgments

Figures 1 through 5 by

Jill Sack Johnson.

Figure 1 adapted from Good

and Johnson (1978).

For Additional Information

Boudreau, G. W. 1968. Alarm sounds and responses of

birds and their application in controlling problem

species. Living Bird 7:27-46.

Boudreau, G. W. 1972.

Factors relating to alarm stimuli in bird control. Proc.

Vertebr. Pest Conf. 5:121-123.

Erdman, S. S. 1981.

Setting up an effective urban blackbird roost control

program. Proc. Bird Control Sem. 8:38-42.

Erdman, S. S. 1982. Public

relations and successful blackbird roost management.

Proc. Great Plains Wildl. Damage Control Workshop

5:252-259.

Garner, K. M. 1978.

Management of blackbird and starling winter roost

problems in Kentucky and Tennessee. Proc. Vertebr. Pest

Conf. 8:54-59.

Good, H. B., and D. M.

Johnson. 1976. Experimental tree trimming to control an

urban winter blackbird roost. Proc. Bird Control Sem.

7:54-64.

Good, H. B., and D. M.

Johnson. 1978. Nonlethal blackbird roost control. Pest

Control 46:14ff.

Mott, D. F. 1980.

Dispersing blackbirds and starlings from objectionable

roost sites. Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 9:38-42.

Mott, D. F. 1985.

Dispersing blackbird-starling roosts with helium-filled

balloons. Proc. East. Wildl. Damage Control Conf.

2:156-162.

Neff, J. A., and R. T.

Mitchell. 1955. The rope firecracker; a device to

protect crops from bird damage. US Dep. Agric. Fish

Wildl. Serv., Wildl. Leaflet No. 365. 8 pp.

Schmidt, R. H., and R. J.

Johnson. 1983. Bird dispersal recordings - an overview.

Pages 43-65 in D. E. Kaukeinen, ed. Vertebr. Pest

Control Manage. Materials, 4th Symp. ASTM STP 817, Am.

Soc. for Testing and Materials, Philadelphia.

US Fish and Wildlife

Service. 1978. Controlling blackbird/starling roosts by

dispersal. Publ. ADC 103. US Dep. Agric., Washington,

DC. 4 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom Robert

M. Timm Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

E-24

01/08/2007

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|