|

|

|

|

|

BIRDS: American Crows |

|

|

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Netting to exclude crows

from high-value crops or small areas.

Protect ripening corn in

gardens by covering each ear with a paper cup or sack

after the silk has turned brown.

Widely-spaced lines or

wires placed around sites needing protection may have

some efficacy in repelling crows, but further study is

needed.

Cultural Methods

Alternate or decoy foods;

example: scatter whole corn, preferably softened by

water, through a field to protect newly planted corn

seedlings.

Frightening

Use with roosts, crops,

and some other situations. Frightening devices include

recorded distress or alarm calls, pyrotechnics, various

sound-producing devices, chemical frightening agents (Avitrol®),

lights, bright objects, high-pressure water spray, and,

where appropriate, shotguns.

Repellents,

None are registered.

Toxicants ,

None are registered

Trapping

Check laws before

trapping. Australian crow decoy traps may be useful near

a high-value crop or other areas where a resident

population is causing damage. Proper care of traps and

decoy birds is necessary.

Capture single crows

uninjured in size No. 0 or No. 1 steel traps that have

the jaws wrapped with cloth or rubber.

Shooting and Hunting

Helpful as a dispersal or

frightening technique but generally not effective in

reducing overall crow numbers. Crows may be hunted

during open seasons. Check with your state wildlife

agency for local restrictions.

Identification

The American crow (Fig. 1)

is one of America’s best-known birds. Males and females

are outwardly alike. Their large size (17 to 21 inches

[43 to 53 cm] long), completely coal-black plumage, and

familiar “caw caw” sound make them easy to identify.

They are fairly common in areas near people, and tales

of their wit and intelligence have been noted in many

stories.

Three other crows occur in

the continental United States, the fish crow (Corvus

ossifragus), the northwestern crow (Corvus caurinus),

and the Mexican crow (Corvus imparatus). Fish crows are

primarily inhabitants of the eastern and southeastern

coastal United States, but their range extends into the

eastern edges of Oklahoma and Texas. Fish crows are

somewhat smaller than American crows, but in the field

they appear much alike. They can be distinguished,

however, by their calls — the fish crow call is a short,

nasal “ca,” “car,” or “ca-ha.” Northwestern crows, as

their name implies, occur in the northwest along the

coastal strip from Washington to Alaska. They are most

often seen foraging along beaches. Northwestern crows

are smaller than American crows, but in Washington state

these two species may hybridize. Mexican crows occur in

south Texas (Brownsville area) primarily during fall and

winter and are fairly small for crows. Their voice is a

low froglike “gurr” or “croak” or, in some areas, a

higher-pitched “creow.”

Ravens are similar to

crows in appearance. Two species occur in the

continental United States, the common or northern raven

(Corvus corax) and Chihuahuan or white-necked raven (Corvus

cryptoleucus). The common raven is found from the

foothills of the Rockies westward, northward to Alaska

and eastward across Canada and some northern U.S.

states, and locally in the Appalachian mountains. Common

ravens can be distinguished from crows by their larger

size, call, wedge-shaped tail, and flight pattern that

commonly includes soaring or gliding. In contrast, crows

have a frequent steady wing-beat with little or no

gliding.

Chihuahuan ravens occur in

the Southwest, including portions of western Kansas,

Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona and

rarely in south-central Nebraska. This raven, which is

smaller than the common raven and somewhat larger than

the American crow, can be distinguished from the crow by

its call, slightly wedge-shaped tail, and flight pattern

that includes gliding. The white neck feathers, which

account for its other name, are seldom visible in the

field.

Range

American crows are widely

distributed over much of North America. They breed from

Newfoundland and Manitoba southward to Florida and

Texas, and throughout the West, except in the drier

southwestern portions. During fall, crows in the

northern parts of their range migrate southward and

generally winter south of the Canada-US border.

Habitat

American crows do best in

a mixture of open fields where food can be found and

woodlots where there are trees for nesting and roosting.

They commonly use woodlots, wooded areas along streams

and rivers, farmlands, orchards, parks, and suburban

areas. Winter roosting concentrations of crows occur in

areas that have favorable roost sites and abundant food.

Food Habits

Crows are omnivorous,

eating almost anything, and they readily adapt food

habits to changing seasons and available food supply.

They belong to a select group of birds that appear

equally adept at live hunting, pirating, and scavenging.

Studies show that crows consume over 600 different food

items.

About one-third of the

crow’s annual diet consists of animal matter, including

grasshoppers, beetles, beetle larvae (white grubs,

wireworms), caterpillars, spiders, millipedes, dead

fish, frogs, salamanders, snakes, eggs and young of

birds, and carrion such as traffic-killed animals. The

remainder of the crow’s diet consists of vegetable or

plant matter. Corn is the principal food item in this

category, much of it obtained from fields after harvest.

Crows also consume acorns, various wild and cultivated

fruits, watermelon, wheat, sorghum, peanuts, pecans,

garbage, and miscellaneous other items.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Crows are among the most

intelligent of birds. Experiments indicate that American

crows can count to three or four, are good at solving

puzzles, have good memories, employ a diverse and

behaviorally complex range of vocalizations, and quickly

learn to associate various noises and symbols with food.

One report describes an American crow that dropped palm

nuts (Washingtonia sp.) onto a residential street, then

waited for passing automobiles to crack them. Crows are

keen and wary birds. Consider the number of crows that

scavenge along highways; how many have you seen hit by

autos? Crows can mimic sounds made by other birds and

animals and have been taught to mimic the human voice.

The myth that splitting the tongue allows a crow to talk

better, however, is not true and is needlessly cruel.

Crows often post a

sentinel while feeding. Although studies indicate that

the sentinel may be part of a family group, unrelated

crows and other birds in the area likely benefit from

the sentinel’s presence.

Crows begin nesting in

early spring (February to May, with southern nests

starting earlier than northern ones) and build a nest of

twigs, sticks, and coarse stems. Crow pairs appear to

remain together throughout the year, at least in

nonmigratory populations, and pairs or pair bonds are

likely maintained even within large winter migratory

flocks. The nest, which is lined with shredded bark,

feathers, grass, cloth, and string, is usually built 18

to 60 feet (5 to 18 m) above ground in oaks, pines,

cottonwoods, or other trees. Where there are few trees,

crows may nest on the ground or on the crossbars of

telephone poles. The average clutch is 4 to 6 eggs that

hatch in about 18 days. Young fledge in about 30 days.

Usually there is 1 brood per year, but in some southern

areas there may be 2 broods. Both sexes help build the

nest and feed the young, and occasionally offspring that

are 1 or more years old (nest associates) help with

nesting activities. The female incubates the eggs and is

fed during incubation by the male and nest associates.

The young leave the nest at about 5 weeks of age and

forage with their parents throughout the summer. Later

in the year, the family may join other groups that in

turn may join still larger groups. The larger groups

often migrate in late fall or winter.

Few crows in the wild live

more than 4 to 6 years, but some have lived to 14 years

in the wild and over 20 years in captivity. Recently, a

bird bander reported a crow that had lived an incredible

29 years in the wild. Adult crows have few predators,

although larger hawks and owls and occasionally canids

take some. Brood losses result from a variety of factors

including predation by raccoons (Procyon lotor),

great-horned owls (Bubo virginianus), and other

predators; starvation; and adverse weather.

One important and

spectacular aspect of crow behavior is their

congregation into huge flocks in fall and winter. Large

flocks are the result of many small flocks gradually

assembling as the season progresses, with the largest

concentration occurring in late winter. The Fort Cobb

area in Oklahoma, a communal roost site, holds several

million crows each winter. In Nebraska, Wisconsin, and

possibly other states, crows appear to be roosting more

commonly in towns near people, resulting in mixed

opinions on how to deal with them. These flocks roost

together at night and disperse over large areas to feed

during the day. Crows may commonly fly 6 to 12 miles (10

to 20 km) outward from a roost each day to feed.

Recent radio-telemetry

studies indicate that roosting crows may have two

distinct daily movement patterns. Some fly each day to a

stable territory, called a diurnal activity center,

which is maintained by four or five birds throughout the

winter and apparently then used as a nesting site in

spring. Although these stable groups of crows may stop

at superabundant food sources such as landfills,

individuals within the groups typically fly different

routes and make different stops. Other crows appear to

be unattached and without specific daily activity

centers or stable groups. Although they use the same

roosts as the activity-cen-ter crows, these unattached

birds, possibly migrants, are not faithful to any

specific location or territory and more regularly feed

at sites such as landfills.

Ongoing changes in

land-use patterns may result in associated impacts on

crow populations and behavior. Historically, crow

populations have benefited from agricultural development

because of grains available as a food supply and because

trees became established in prairie areas where

agriculture and settlement suppressed natural fires. The

combination of food and tree availability favored crows,

and in some areas with abundant food and available roost

sites, large winter roosting concentrations became

established. As the current trend toward sustainable

agricultural systems continues, which may include a

variety of crops and rotations with nongrain crops, food

availability and associated patterns of crow roosts may

change.

The growing number of

crows that nest and roost in urban areas also raises

questions. Are urban habitats now selected because of

adaptive changes in crow behavior, or are changes in

rural settings making urban sites comparably more

suitable? One study described two neighboring but

distinct crow nesting populations — one that was urban

and somewhat habituated to people and another that was

rural and relatively wary of people. Will crows that are

hatched in urban areas be habituated to people to such

an extent that they will be more difficult than their

rural counterparts to disperse from problem sites?

Understanding such factors may lead to better options

for managing crows in ways compatible with the needs of

people.

Damage and Damage Identification

Complaints associated with

crow damage to agriculture were more common in the 1940s

than they are today. Although surveys indicate that

overall crow numbers have not changed appreciably, the

populations appear to be more scattered during much of

the year. This change has resulted apparently from the

crows’ response to changing land-use patterns. Farming

has become more prevalent in some areas, generally with

larger fields. Woodland areas are generally smaller, and

trees and other resources in urban sites provide crow

habitat. Overall, the amount and degree of damage is

highly variable from place to place and year to year.

Several variables enter into the complex picture of crow

damage, including season, local weather, time of

harvest, amount of crop production, and availability and

distribution of wild mast, insects, and other foods.

Although crows cause a

variety of damage problems, many of these are more

commonly associated with other animal species. Crows may

damage seedling corn plants by pulling the sprouts and

consuming the kernels. Similar damage may also be caused

by other birds (pheasants, starlings, blackbirds) and

rodents (mice, ground squirrels). Crows at times damage

ripening corn during the milk and dough stages of

development. Such damage, however, is more commonly

caused by blackbirds; for further information, see

Blackbirds. Crows consume peanuts when they are

windrowed in fields to dry, but other birds, especially

grackles, cause the greatest portion of this damage.

Crows may also damage other crops, including ripening

grain sorghum, commercial sunflowers, pecans, various

fruits, and watermelons. In rare situations, crows may

attack very young calves, pigs, goats, and lambs,

particularly during or shortly after birth. This

problem, which is more often associated with magpies or

ravens, is most likely to happen where livestock births

occur in unprotected open fields near large

concentrations of crows.

Another complaint about

crows is that they consume the eggs and sometimes the

young of waterfowl, pheasants, and other birds during

the nesting season. Overall, such crow depredation

probably has little effect on the numbers of these

birds. However, it can be a problem of concern locally,

particularly where breeding waterfowl are concentrated

and where there is too little habitat cover to conceal

nests. For example, nests are more easily found by

crows, as well as by other predators, when located in a

narrow fence row or at the edge of a prairie pothole

that has little surrounding cover.

Large fall and winter crow

roosts cause serious problems in some areas,

particularly when located in towns or other sites near

people. Such roosts are objectionable because of the

odor of the bird droppings, health concerns, noise, and

damage to trees in the roost. In addition, crows flying

out from roosts each day to feed may cause agricultural

or other damage problems. On the other hand, the diet of

crows may be beneficial to agriculture, depending on the

time of year and surrounding land use.

Finally, in some

situations, large crow flocks may become a factor in

spreading disease. At times, they feed in and around

farm buildings, where they have been implicated in the

spread of transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE) among

swine facilities. At other times, large crow flocks near

wetland areas may increase the potential for spread of

waterfowl diseases such as avian cholera. The scavenging

habits of crows and the apparent longer incubation time

of the disease in crows are factors that increase the

potential for crows to spread this devastating disease.

Also, crow and other bird (blackbird, starling) roosts

that have been in place for several years may harbor the

fungus (Histoplasma capsulatum) that causes

histoplasmosis, a disease that can infect people who

breathe in spores when a roost is disturbed.

Legal Status

Crows are protected by the

Migratory Bird Treaty Act, a federal act resulting from

a formal treaty signed by the United States, Canada, and

Mexico. However, under this act, crows may be controlled

without a federal permit when found “committing or about

to commit depredations upon ornamental or shade trees,

agricultural crops, livestock, or wildlife, or when

concentrated in such numbers and manner to constitute a

health hazard or other nuisance.”

States may require permits

to control crows and may regulate the method of take.

Federal guidelines permit states to establish hunting

seasons for crows. During these seasons, crows may be

hunted according to the regulations established in each

state. Regulations or interpretation of depredation

rules may vary among states, and state or local laws may

prohibit certain control techniques such as shooting or

trapping. Check with local wildlife officials if there

is any doubt regarding legality of control methods.

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Exclusion generally is not practical for most crow

problems, but might be useful in some situations. For

example, nylon or plastic netting might be useful in

excluding crows from high-value crops or small areas.

Protect ripening corn in small gardens from crow or

other bird damage by placing a paper cup or sack over

each ear after the silk has turned brown. The dried

brown silk indicates that the ear has been pollinated by

the corn tassels, a necessary step in corn grain

development.

Lines. Another excluding

or repelling technique used historically to protect

fields from crows is stretching cord or fine wire at

intervals across the field at heights about 6 to 8 feet

(1.8 to 2.4 m) above the ground. Sometimes aluminum or

cloth strips or aluminum pie pans were tied to the

wires. More recently, the concept of stretching widely

spaced lines or wires over or around sites needing

protection from certain birds has received increased

attention. Crows were included in two studies at

sanitary landfills, but results were somewhat

conflicting. One report from South Carolina indicated

that a 20 x 20-foot (6 x 6-m) wire grid repelled crows,

but another from New York indicated that parallel wires

stretched 10 x 10 feet (3 x 3 m) apart and 80 x 80 feet

(24 x 24 m) above the ground did not repel them.

The reason this technique

has worked for certain birds is not completely clear,

but the wires appear to represent an obstacle that is

difficult for a flying bird to see, especially when

rapid escape may be necessary. Various species respond

differently to lines, and generally adult birds are more

repelled by lines than juveniles. Other factors such as

season and/or biological activity of the birds, type of

lines or wires, spacing, and height need further

research and development to better understand the

potential usefulness of lines in bird management.

Cultural Methods

Agricultural Crops. Some reports indicate that

providing an alternate or decoy food source will reduce

crop damage caused by crows. An example would be

scattering a grain such as whole corn, preferably

softened by water, through a field where crows are

damaging newly planted corn seedlings. Although this

technique has been reported to be helpful in some

situations, it has not been well tested.

Tree Roosts. Thinning

branches from specific roost trees or thinning trees

from dense groves reduces the availability of perch

sites and opens the trees to weather effects. Such

vegetation management has effectively dispersed

starling/blackbird roosts, and the same biological

concepts indicate probable effectiveness in dispersing

crow roosts. When roosts occur in a small number of

landscape trees near homes or along streets, they

usually are in fairly dense trees where thinning the

branches will reduce the trees’ attractiveness as

roosts. Roosts in tree groves or woodlots usually occur

in dense stands of young trees. Thinning about one-third

of the trees improves the tree stand, especially if

marked by a professional forester. Such thinning

successfully dispersed blackbird/star-ling roosts from

research woodlots in Ohio and Kentucky, and from at

least two problem roost sites in Nebraska. In dense

cedar thickets, bulldozing strips through the roost site

to remove one-third of the habitat has also been

successful in dispersing birds, but soil disturbance

with this method may be hazardous if soils harbor fungal

spores of the human respiratory disease histoplasmosis.

For further information on roost dispersal, see Bird

Dispersal Techniques.

Frightening

Frightening is effective in dispersing crows from

roosts, some crops, and other troublesome sites. In a

recent study in California, crows were successfully

dispersed from urban crow roosts using tape-recorded

“squalling” calls (given by a crow struggling to escape

from a predator) and a portable tape player commonly

used by hunters to attract animals. Such dispersal

allows crows to be moved from problem sites to sites

where they are less likely to interfere with people.

In addition to recorded

distress or alarm calls, frightening devices include

gas-operated exploders, battery-operated alarms,

pyrotechnics, (shellcrackers, bird bombs), chemical

frightening agents (see Avitrol® below), lights (for

roosting sites at night), bright objects, clapper

devices, and various other noisemakers. Beating on tin

sheets or barrels with clubs can help in scaring birds.

Spraying birds as they land, with water from a hose or

from sprinklers mounted in the roost trees, has helped

in some situations. Hanging mylar tape in roost trees

may be helpful in urban areas. A combination of several

scare techniques used together works better than a

single technique used alone. Vary the location,

intensity, and types of scare devices to improve their

effectiveness. Supplement frightening techniques with

shotguns, where permitted, to improve their

effectiveness in dispersing crows. Ultrasonic (high

frequency, above 20 kHz) sounds are not effective in

frightening crows and most other birds because, like

humans, they do not hear these sounds. For a more

detailed discussion of frightening techniques, see Bird

Dispersal Techniques.

Animated “crow-killing”

owl models can frighten crows from gardens and small

fields. These are made from a plastic owl model with a

crow model attached in such a way that the crow appears

to be in the owl’s talons. Movement is supplied by

mounting the model on a weather vane and by adding wind-

or battery-powered wings to the crow.

Clapper devices (Tomko

Timer-Clapper) have been reported by the Nebraska Game

and Parks Commission as successful in dispersing crows

from waterfowl concentration areas where crow roosting

was destroying a multiple-row shelterbelt and where

there was concern that crows were aggravating the spread

of avian cholera. A clapper device intermittently

“claps,” producing a sound much like a twig snapping or

like two boards clapping together. The device can be

placed up in trees or at other sites close to crow

perches, making it perhaps more significant to crows as

a frightening device. Clappers have also been used to

frighten and disperse other birds (starlings, grackles,

swallows) and to repel deer at night. Like many other

frightening techniques, clappers appear to be most

effective with wary populations. Populations that have

habituated to people or disturbance to such an extent

that they have lost their wariness, may not respond.

Avitrol®. Avitrol® (active

ingredient: 4-aminopyridine) is a Restricted Use

Pesticide and chemical frightening agent, available in a

whole-corn bait formulation (Double Strength Whole Corn)

for use in dispersing crows. It is only for sale to

certified applicators or persons under their direct

supervision and only for those uses covered by the

applicator’s certification.

Avitrol® baits contain a

small number of treated grains mixed with many others

that are untreated. Birds that eat the treated portion

of the bait behave erratically and/or give warning cries

that frighten other birds from the area. Generally,

birds that eat the treated particles die. Overall,

because of the type of damage problems associated with

crows, Avitrol® is unlikely to be used often. This

product is included here, however, because situations

may arise in which its use would be helpful. Before

using this product for crow control, it is best to

contact a qualified person trained in bird control work

(someone from the Cooperative Extension or

USDA-APHIS-Animal Damage Control, for example) for

technical assistance. For additional information on

Avitrol®, see Blackbirds and European Starlings.

Repellents

No repellents are registered for crow control.

Recent studies show that conditioned aversion learning,

a form of repellency, can reduce egg and possibly fruit

and grain crop depredation by crows. Further work and

registration of an appropriate agent for producing a

conditioned aversion response are needed.

Toxicants

No toxicants are registered for crow control.

Special Local Needs 24(c) registrations have been sought

for DRC-1339 (3-chloro p-toluidine hydrochloride) by

USDA-APHIS-ADC for limited, small-scale use.

Trapping

Trapping is often less attractive than other

techniques because of the wide-ranging movements of

crows, the time necessary to maintain and manage traps,

and the number of crows that can be captured compared to

the total number in the area. Trapping and removing

crows, however, can be a successful method of control at

locations where a small resident population is causing

damage or where other techniques cannot be used.

Examples include trapping damage-causing crows near a

high-value crop or in an area where nesting waterfowl

are highly concentrated.

Two types of traps can be

used to successfully capture crows. First, individual

crows may be captured uninjured with No. 0 or No. 1

steel traps that have the jaws wrapped with cloth or

rubber. These sets are most successful if placed at

vantage points in areas habitually used by crows or if

baited with a dummy nest containing a few eggs. Check

such traps at least twice daily. Crows captured in this

way might be used, if necessary, as initial decoys in

the Australian crow trap described below, but the small

number of captures is otherwise unlikely to affect a

damage situation.

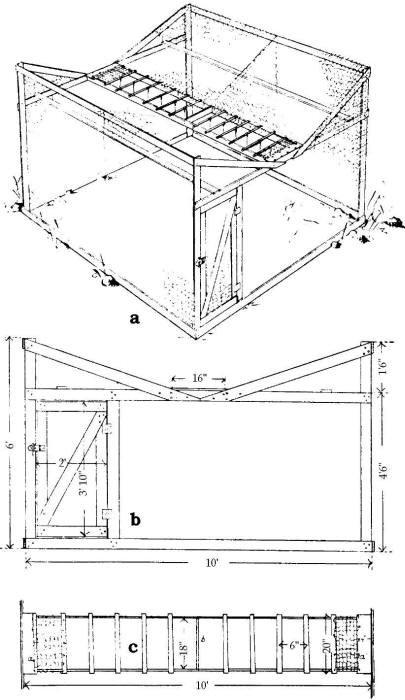

A second and more commonly

used trap for crows is the Australian Crow Trap (Fig.

2), a type of decoy trap. These traps are most

successful if used during the winter when food is

scarce. Australian crow traps should be at least 8 to 10

feet (2.4 to 3 m) square and 5 to 6 feet (1.5 to 1.8 m)

high. If desired, construct the sides and top in panels

to facilitate transportation and storage. Place the trap

where crows are likely to congregate. The most

attractive bait is meat (such as slaughterhouse offal,

small animal carcasses) or eggs. Whole kernel corn, milo

heads, watermelon, and poultry feed may also work and

may be preferred where carnivores such as feral dogs

might be attracted to the trap. Place the bait under the

ladder portion of the trap. Also provide water. After

the first baiting, the trap should not be visited for 24

hours. Once the birds begin to enter the trap, it should

be cared for daily. Replace the bait as soon as it loses

its fresh appearance. Remove all crows captured except

for about five to be left in the trap as decoys. Remove

captured crows after sunset when they are calm (to

facilitate handling).

Fig. 2. Australian crow

trap: (a) completed trap, (b) end view, and (c) plan of

“ladder” opening.

Should any nontarget birds

be captured, release them unharmed immediately.

Euthanize captured crows humanely by carbon dioxide

exposure or cervical dislocation. A well-main-tained

decoy trap can capture a number of crows each day,

depending on its size and location, the time of year,

and how well the trap is maintained.

A recent study in Israel

of hooded crows (Corvus corone), which are about the

same size as American crows, indicated that decoy crows

were more important than bait to trap success. Using one

hooded crow decoy bird, however, appeared to be as

effective as using three to four, and fleshy baits did

increase success in some cases. To prevent hooded crow

escape, the ladder gap width of the American model was

reduced from 18 to 12 inches (45 to 30 cm), and 1.5 x

0.8-inch (4 x 2-cm) square rungs were used instead of

3-inch (8-cm) diameter metal rods. The potential

response of American crows to such trap modifications is

unknown but merits study.

Shooting and Hunting

Shooting is more effective

as a dispersal technique than as a way to reduce crow

numbers. Crows are wary and thus difficult to shoot

during daylight hours. They may be attracted to a

concealed shooter, however, by using crow decoys or

calls, or by placing an owl effigy in a conspicuous

location. Generally, the number of crows killed by

shooting is very small in relation to the numbers

involved in pest situations. However, shooting can be a

helpful technique to supplement and reinforce other

dispersal techniques when the goal is to frighten and

disperse crows rather than specifically to reduce

numbers. For more details on dispersal, see Bird

Dispersal Techniques.

Crow hunting during open

season can be encouraged in areas where crows cause

problems. The helpfulness of hunting as a control

technique varies depending on crow movements, the season

in which the damage occurs, and other factors. Another

consideration is that crows tend to be more wary of

people when they are hunted and thus more easily

dispersed from roosting or other areas where their

presence is a problem. Further study is needed to better

understand the relationships between hunting and

wariness, and whether a pattern exists that might be

used to improve crow management programs.

Economics of Damage and Control

The economics of crow

damage often center around a widespread controversy over

whether crow feeding habits are harmful or beneficial.

Some say that crows earn their keep by taking harmful

insects and cleaning up carrion. Others say the damage

done far outweighs any beneficial aspects. Despite some

studies of the crow diet, little quantitative

information is available on the overall economic impacts

of crows. In addition, it appears likely that the

economics of crows in relation to agriculture or people

have changed from what they were 30 or more years ago

when many crow studies were done.

At one time several state

legislatures appropriated funds for bounties on crows

and for bombing crow roosts, and suggested all-out

efforts to eradicate the crow. Now, most state wildlife

and agriculture departments report only a few scattered

complaints of crow damage each year. At times, however,

individual farms or crops do suffer severe damage, and

concerns about large crow roosts in urban areas near

people appear to be increasing. Individuals experiencing

damage problems should weigh the costs of control

against the amount of damage, then work with the proper

authorities to develop a control program.

On the beneficial side,

the crow diet includes large numbers of insects

considered harmful to agriculture, as well as mice and

carrion. In addition, their consumption of waste grain

left in fields may help prevent undesirable volunteer

corn in the following year’s crop. The fact that crows

also eat snakes may be considered a benefit by some

people.

Overall, crow and other

bird problems can be difficult or frustrating to resolve

satisfactorily with the methods and understanding

currently available. Persistence and use of a variety of

techniques may be necessary to help prevent damage. In

addition, further research is needed to develop damage

control methods based on an understanding of bird

problems in relation to agricultural and urban

landscapes and other natural resource systems where

damage occurs.

Acknowledgments

The references listed

under “For Additional Information” and many others were

used in preparing this chapter. Gratitude is extended to

the authors and the many researchers and observers who

contributed to this body of knowledge. I extend special

appreciation to R.

W. Altman, retired

Oklahoma State University extension wildlife specialist,

for his contributions as co-author of the first edition

of this chapter. I also thank M. M. Beck, R. M. Case, R.

Kelly, and R. Ross for comments and helpful advice on

the first edition; J. Andelt provided typing and

technical assistance. I gratefully acknowledge M. M.

Beck, C. S. Brown, R. M. Case, and R. L. Knight for

valuable reviews of this second edition.

Figure 1 by Emily Oseas

Routman, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Figure 2 from E. R.

Kalmbach (1939).

For Additional Information

Arvin, J., J. Arvin, C. Cottam, and G. Unland. 1975.

Mexican crow invades south Texas. Auk 92:387-390.

Bent, A. C. 1964. Life

histories of North American jays, crows and titmice.

Dover Pub., Inc., New York. 495 pp.

Chamberlain-Auger, J. A.,

P. J. Auger, and E. G. Strauss. 1990. Breeding biology

of American crows. Wilson Bull. 102:615-622.

Conover, M. R. 1985.

Protecting vegetables from crows using an animated

crow-killing owl model. J. Wildl. Manage. 49:643-645.

Dimmick, C. R., and L. K.

Nicolaus. 1990. Efficiency of conditioned aversion in

reducing depredation by crows. J. Appl. Ecol.

27:200-209.

Good, E.E. 1952. The life

history of the American crow, Corvus brachyrhynchos

Brehm. Ph.D. Diss., The Ohio State Univ., Columbus. 203

pp.

Goodwin, D. 1976. Crows of

the world. Comstock Publ. Assoc., a div. Cornell Univ.

Press, Ithaca, New York. 354 pp.

Gorenzel, W. P., and T. P.

Salmon. 1993. Tape-recorded calls disperse American

crows from urban roosts. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 21:334-338.

Friend, M. 1987. Avian

cholera. Pages 69-82 in

M. Friend, ed. A field

guide to wildlife diseases, Volume 1. General field

procedures and diseases of migratory birds, US Dep.

Inter., Fish Wildl. Serv., Resour. Publ. 167,

Washington, DC.

Houston, C. S. 1977.

Changing patterns of Corvidae on the prairies. Blue Jay

35:149-155.

Ignatiuk, J. B., and R. G.

Clark. 1991. Breeding biology of American crows in

Saskatchewan parkland habitat. Can. J. Zool. 69:168-175.

Johnsgard, P. A. 1979.

Birds of the Great Plains, breeding species and their

distribution. Univ. Nebraska Press, Lincoln. 539 pp.

Kalmbach, E. R. 1937.

Crow-waterfowl relationships. US Dep. Agric., Cir. 433,

Washington, DC. 36 pp.

Kalmbach, E. R. 1939. The

crow in its relation to agriculture. US Dep. Agric.,

Farmer’s Bull. No. 1102, rev. ed. Washington, DC. 21 pp.

Kilham, L. 1989. The

American crow and the common raven. Texas A&M Univ.

Press, College Station. 255 pp.

Knight, R. L., D. J.

Grout, and S. A. Temple. 1987. Nest-defense behavior of

the American crow in urban and rural areas. Condor

89:175-177.

Knopf, F. L., and B. A.

Knopf. 1983. Flocking pattern of foraging American crows

in Oklahoma. Wilson Bull. 95:153-155.

Maccarone, A. D. 1987.

Sentinel behaviour in American Crows. Bird Behav.

7:93-95.

Martin, A. C., H. S. Zim,

and A. L. Nelson. 1951. American wildlife and plants, a

guide to wildlife food habits. Dover Publ., Inc., New

York. 500 pp.

Mott, D. F., J. F. Besser,

R. R. West, and J.W. DeGrazio. 1972. Bird damage to

peanuts and methods for alleviating the problem. Proc.

Verteb. Pest Conf. 5:118-120.

Moran, S. 1991. Control of

hooded crows by modified Australian traps.

Phytoparasitica 19:95-101.

Pochop, P. A., R. J.

Johnson, D. A. Agüero, and

K. M. Eskridge. 1990. The

status of lines in bird control — a review. Proc. Verteb.

Pest Conf. 14:317-324.

Schorger, A. W. 1941. The

crow and the raven in early Wisconsin. Wilson Bull.

53:103-106.

Stouffer P. C., and D. F.

Caccamise. 1991. Capturing American crows using alpha-chloralose.

J. Field Ornithol. 62:450-453.

Stouffer P. C., and D. F.

Caccamise. 1991. Roosting and diurnal movements of

radio-tagged American crows. Wilson Bull. 103:387-400.

Sullivan, B. D., and J. J.

Dinsmore. 1990. Factors affecting egg predation by

American crows.

J. Wildl. Manage.

54:433-437.

Terres, J. K. 1980. The

Audubon Society encyclopedia of North American birds.

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York. 1109 pp.

Weeks, R. J. 1984.

Histoplasmosis, sources of infection and methods of

control. US Dep. Health Human Serv., Public Health Serv.,

Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, Georgia. 8 pp.

Yahner, R. H., and A. L.

Wright. 1985. Depredation on artificial ground nests:

effects of edge and plot age. J. Wildl. Manage.

49:508-513.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom; Robert

M. Timm; Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|